Configuration of Subjectivities of English Language Teachers as NNESTs in the Frame of Colombian Language Policies: A Narrative Study.

Leidy Yisel Gómez Vásquez 20151062011

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas School of Science and Education

Configuration of Subjectivities of English Language Teachers as NNESTs in the Frame of Colombian Language Policies: A Narrative Study.

Leidy Yisel Gómez Vásquez 20151062011

Thesis Director: Carmen Helena Guerrero. PhD.

A Research Presented as a Requirement to Obtain the Degree as MA in Applied Linguistics to the Teaching of English

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas School of Science and Education

NOTE OF ACEPTANCE

______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________

Thesis Director:

__________________________________________ Carmen Helena Guerrero. PhD.

Jurors:

__________________________________________

UNIVERSIDAD DISTRITAL FRANCISCO JOSÉ DE CALDAS

Acuerdo 19 de 1988 del Consejo Superior Universitario

Artículo 177. “La Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas no será responsable de las

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I want to thank God for giving me the strength to believe and keep working.

I am deeply grateful to my beloved husband for his support, patience, encouragement and everything that he does to show me his love.

I appreciate the support and guidance from my thesis director, Professor Carmen Helena Guerrero. Thanks for letting me be part of your wonderful research group and for sharing your knowledge with me. I was honored.

Thanks to my family, friends, study partners, university professors, especially to Harold Castañeda, research participants, and to Luz Stella Hernández and my coworkers at Universidad de la Sabana. Your advice, support, knowledge, constructive criticism and experiences made this

12 13 16 17 24 25 25 26 28 28 28 30 34 41 41 42 46 49 51

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page Number

ABSTRACT………

INTRODUCTION………..

CHAPTER I: STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM………

Needs Analysis………

Statement of the Problem ………

Research Question………

Objectives ………

Rationale………...

CHAPTER II: STATE OF THE ART……….

Background to the study………...…

Some studies about subjectivities………...

What has been done in relation to NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy……….…...

Language policies: a widely researched topic ……….………

CHAPTER III: LITERATURE REVIEW………...…

Theoretical Framework ………

A theoretical approximation to subjectivities ……….……….…

The controversial issue of NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy……….…..

Language policies: from theory to reality……….…

54

55

60

62

66

66

71

94

99

101 CHAPTER IV: RESEARCH DESIGN………..…

Type of study………...

Context and Participants……….……….……….…..

Instruments ……….……….……….…………..……

CHAPTER V: DATA ANALYSIS………....

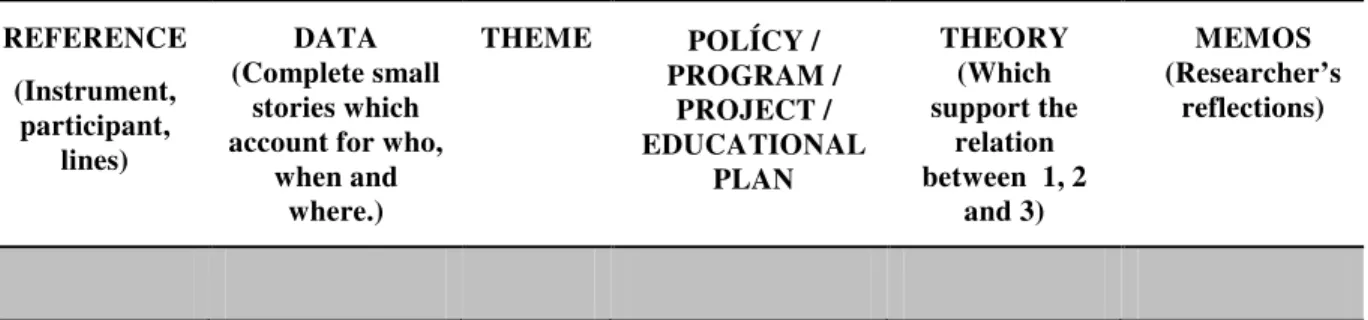

Framework of analysis ……….………..

Findings ………..

CHAPTER VI: CONCLUSIONS………... CHAPTER VII: IMPLICATIONS AND FURTHER RESEARCH….………….….….….. REFERENCES……….………….……….……….…………

LIST OF APPENDIXES

Appendix 1: Survey Model

Appendix 2: Consent Form Model

Appendix 3: Focus Group Protocol

Appendix 4: Time Line Sample

Appendix 5: Written Narrative Protocol

Appendix 6: Narrative Interview Protocols

Appendix 7: Data Analysis Matrix Sample

Appendix 8: Reduction of Themes Table

53

57

58

65

68

71

LIST OF FIGURES

Page Number

Figure 1: Co-relations of the theory constructs………..…

Figure 2: The Three Dimensional Narrative Life Space………....

Figure 3: Dimensions of Narrative Research..…….……….……….……….

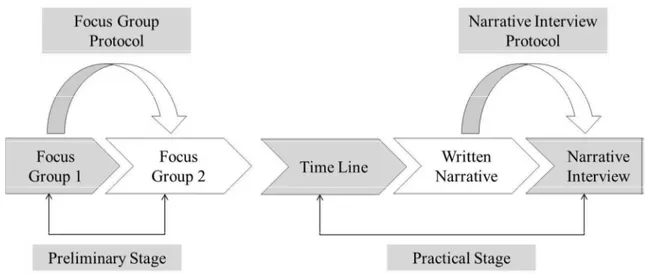

Figure 4: Data Collection Process………..……

Figure 5: SSA Data Analysis Process……….

LIST OF TABLES

Page Number

ABSTRACT

This paper describes the process carried out to report on the configuration of professional subjectivities by analyzing the narratives of four Colombian English language (EL) teachers as Non Native English Speaking Teachers (NNESTs), and their relation to language policies.

Historically, language policies in Colombia have been designed not taking into account the needs, desires and experiences of the people involved in their application, especially teachers. (González, 2007; Guerrero, 2008, 2009, 2010; Mejia, 2012; Usma, 2009, among others).

Consequently, it is my aspiration that the stories portrayed here might shed light on the policy making, and somehow, guide the people who have the responsibility to generate them.

Considering my personal experiences, the literature produced in the field of subjectivities, NNESTs and Native English Speaking Teachers (NESTs) dichotomy, and subjectivities, I was able to identify that not much research work integrating those three fields has been made in Colombia, gap which this study intents to help to fill.

This is a qualitative-narrative study in which I used focus groups, written narratives and narrative interviews as instruments to collect data from the participants who belong to different universities and schools in Colombia.

Their stories were analyzed using the Short Story Analysis approach (SSA) and the results allowed me to identify a main category: Re-creating the self: an entangled, changeable and enduring process which shows how the subjectivities of the teachers are influenced by others, the processes of acceptance or rejection that these teachers go through when configuring them, and the role played by knowledge and reflection.

INTRODUCTION

The subject configures his/her subjectivities in diverse ways and taking into account different factors from his social, cultural and historical context, Muñoz (2007) claims that “the subject is not a flat and constant surface, but variable and polyhedral, which implies an awareness of the heterogeneous processes configured in there.” (p. 60). According to Muñoz the subject is at the same time conscience, practice and language. Additionally, Muñoz explains that

subjectivities are inner but they have a public manifestation, which takes place in spaces such as the family, the school, the neighborhood, in local or in national levels. So, there is co-relation between the factors that influence the configuration of subjectivities and the manifestation of such configuration which allows the subject to transform his context and to be transformed by it.

Consequently, based on the understanding of subject and subjectivity, this study aims to uncover the configuration of the subjectivities by EL professional teachers as NNESTs in the frame of Colombian language policies. This study responds to the need of reporting in such configuration in order to help to fill a gap, since a few studies in Colombia have addressed the issue. Its value is based on the premise that revealing the way EL teachers configure their professional subjectivities and the practices that they report to be manifestation of that configuration can enlighten policy makers at the moment of designing language policies in Colombia, especially those which involve the dichotomy between NESTs and NNESTs.

more research work to be developed. Additionally, not many of the studies that I report in the state of the art are narrative ones. In reference to the theoretical concepts that give support to this research, I give an account of the definitions and my interpretation of each of the constructs.

For the purposes of this research study, narratives constituted the best way to unveil the thoughts, interpretations and self-reported practices of the four professional EL teachers from Colombia who participated in the study. As stated by Guerrero (2011) narratives are “systems of understanding that we use to construct and express meaning in our daily lives” (p. 90). Therefore, through narratives it can be visualized what other subjects live and feel based on their actions, words, testimonies, among other representations.

Once the narratives were collected both written and orally, several complete short stories were selected to be analyzed. These short stories had to comply with certain characteristics: to include people (who), places (where) and time (when) and to have a starting point, different events and a sort of conclusion or closing event. These short stories were later analyzed, classified into themes, and categorized.

After conducting the analysis, a single category emerged that was entitled Re-creating the self: an entangled, changeable and enduring process. From this category three directions were identified: the influence of others, the traces of rejection or acceptance towards language policies, and NESTs-NNESTs dichotomy as well as the role of knowledge and reflection on the

configuration of the participants’ subjectivities.

Finally, it was identified that the EL teachers who participated in this study have

field of Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) and the creation of national language policies.

To conclude, this document presents: (a) the problematical situation identified and the supporting process that led me to the formulation of the research question and objectives, (b) an account of similar studies developed in the field of subjectivities, NESTs and NNESTs

dichotomy, and language policies, (c) an explanation of the theoretical constructs that guided the study, (d) the description of the participants and the narrative methodology and instruments used to collect the data, (e) an account of the model carried out to analyze the data and the discussion of the findings, and finally, (f) there is a conclusion section where the research question is

CHAPTER I

STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

Introduction

The design and implementation of language policies in Colombia have been processes carried out without assessing the particular needs of the Colombian context and the expectations of the stakeholders, particularly the teachers, although their experiences could be a useful input to be taken into account as pointed out by Correa and Usma (2013). This research study explores on the construction of subjectivities by analyzing the narratives of Colombian EL professional teachers as NNESTs and the relation of their subjectivities to language policies. The result of this analysis might be a contribution to language policy creation as the analyzed narratives come from actual practice.

This research study belongs to a major project entitled Configuration of Subjectivities of Professional Teachers and Colombian Educational Policies¹ where issues related to policies about New Information and Communication Technologies, and inclusion, were studied as sub-projects by other researchers. This particular study focuses on the way EL Teachers as NNESTs configure their subjectivities in relationship with Colombian language policies. In the next section I will explain the sources that I used to back up the research problem.

______________________________________________________________________________ 1. This research study was developed by the investigation group “Estudios Críticos de Políticas Educativas

Needs analysis

In order to document a problematic situation which could be latter a matter of research, I used three different resources: my personal experience, the literature, and a survey, which became the support for the needs analysis that I present here.

The concern about this research topic first came from the experience of discrimination that I suffered from employers and students who considered me less acceptable to teach English because I am from Colombia. Since I had heard similar complaints from other Colombian teachers, I considered that this could be a topic that deserved attention, for that reason, I started looking for similar studies in Colombia and around the world. I found that much work had been developed in this matter, (Arva and Medgyes, 2000; Clark and Paran, 2007; González, 2007; Hayes, 2009; Ma, 2012; Shibata, 2010; Todd and Pojanapunya, 2009) but I did not find much of this topic of research in Colombia.

In order to create an instrument to collect preliminary data that served for my needs’ analysis, I considered the problematic situations that the authors mentioned above identified in their studies; paraphrasing those problems, I created some statements and placed them in a Likert scale type of survey which contained 11 statements (see Appendix 1). The purpose of this survey was to find out whether the EL teachers in Colombia who took the survey had experienced

similar problems to the ones described by the authors. The teachers who answered were contacted by mail and social networks, they are professional EL teachers, and they work for public or private schools, institutions or universities in Bogotá, Colombia. 10 male and female teachers participated in this survey.

similar. All of them consider inopportune the idealization of the NESTs as fully competent; they also ponder that society is not open to accept diverse forms of teaching that disregard the NESTs as the best model. Likewise, 90% feel they have a different position in English language teaching because they are considered neither the model speaker nor the ideal teacher. On top of that, 70% assert their status was perceived as lower than NESTs, while only 20% state they were treated equally when applying for a teaching job. Finally, even though 80% say that acquiring a native-like pronunciation in their work places was not important, and 60% affirm that they have been evaluated by their teaching experiences, professional preparation and linguistic expertise rather than their first language, only 20% agree that the teacher development programs in their

workplaces are adequate for their social and cultural realities.

Having the results from the survey in hand I turned to another source to document the problem, it was the literature. That was how I identified that the problematic situation in my research study has different levels. One general level holds educational policies as a whole, and a more specific level is related to the main concern of my study: language polices.

Secondly, there are experts on linguistics and sociolinguistics. For instance, in this level there might be experts in pedagogies, didactics, curriculum, and technologies, among others. In Colombia giving preference to foreign institutions such as the British Council has been a

common practice in order to support the creation of language policies. This way, the knowledge produced locally is being underestimated and the preference is given to the results of foreign research studies which are taken without giving them a critical stance and which are replicated without deeming the local characteristics and needs that usually differ from the ones in the countries where such studies were produced (González, 2007; Guerrero, 2008, 2009, 2010; Mejia, 2012; Usma, 2009).

Finally, there are the teachers. Although a lot of research has been produced by

Colombian teachers and specifically by Colombian EL teachers whose scholarly work has been published locally in academic journals like Íkala, CALJ, PROFILE, HOW, among others, there is a common mistaken belief that these practices and research studies are not valid enough or not worthy of being taken into consideration by policy makers. Yet, these research studies are

developed from the inside of the actual classrooms and as a result they have produced knowledge in different areas, such as linguistics, culture, and society, among others. (H. Guerrero, personal communication, September 11th, 2015)

doing so, the subjectivities of the Colombian NESTs´ become molded in certain ways, as it will be revealed in the data analysis chapter.

In addition to what was presented above, another instrument that I used to support the problem was to look for previous studies which had problematized teachers’ subjectivities, NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy, and language policies. These studies are reported from the issues that they problematized. Some of them will be referred again in chapters two and three, but then focusing on the information about their results and some of their theoretical constructs.

To start, few studies have explored the subjectivities of EL teachers, although many studies have approached subjectivities from other disciplines. Meguins and Carneiro (2015) investigated how teachers’ subjectivities are affected by policy demands. Teachers experience conflicts between the levels of satisfaction aimed in contrast to the ones obtained with their labor, creating conflict in their perceptions and practices. But

Likewise, Ali, Turvey and Yandell (2012) highlight that there is an effect of school reforms in England in teachers’ and students’ practices and subjectivities. The agency of teachers and learners, effaced by the dominant discourses is continually being reasserted, and recurrently threatening to destabilize the false simplicities of the standards.

Also, Rojas and Leyton (2010) researched the abrupt introduction of educational policies in Chile and the subjectivity transformation that the teachers in charge of implementing them suffered; they say that a “painful subjectivation” took place and that the teachers showed signs of submission and resistance when analyzing their role.

In reference to the NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy, a lot of studies have produced results in different fields. Firstly, some authors have highlighted the contribution that NNESTs can have in the field of TESOL. They mention the potential benefits that can be taken from our experience, our commitment and our methods to teach. Also, there is a call to research more in this field since these teachers are a majority and usually their necessities, limitations or advantages remain unnoticed. (Arva and Medgyes, 2000; Hayes 2009; Ma, 2010).

Secondly, several authors rely on the higher status given to NESTs over NNESTs. For instance, Hayes (2009) thinks there is a monolithic view of English Language Teaching (ELT) based on Western conception where the “native” is considered better. Besides, Shibata (2010) states that NESTs are considered to be the best model and type of language teacher for NNESTs to follow.

Thirdly, some studies are focused on the differences and similarities found among

NNESTs and NESTs. Arva and Medgyes (2000) assert that some differences have been identified in teaching behavior, language proficiency and socio cultural awareness. In addition, Ma (2012) makes an emphasis on the comparison that students tend to make between NNESTs and NESTs linguistic knowledge.

Finally, some other research studies have focused on the treatment given to NNESTs and NESTS when looking for a job or in relation to working and salary conditions. Todd and

It is also noticeable that the studies described above were developed in other countries but Colombia, consequently it provides an opportunity for additional research. As well, the problems from the reviewed studies have a connection with the role of language and educational policies, as it is shown below.

Extensive research has been conducted regarding educational policies and specifically language policies. In the first place, in Colombia scholars like Correa and Usma (2013), Guerrero (2008, 2009), Guerrero and Quintero (2009), Mejia (2012) and Usma (2009) have problematized the treatment given to English in national educational policies. These scholars have pointed out the emphasis given to English as a neutral language, a language that is indispensable in a globalized world as well as the only language that fits into bilingualism polices, situation that perpetuates the disdain against native and local languages. This corresponds to what Pennycook (1998) named as “colonial mentality” and it refers to the assumptions that the culture or dogmas of the colonizer are more worthy or superior. Similarly, Wang and Lin (2013) mention that the status of English as a global language in East Asia has influenced the creation of policies where Native English Speaking Teachers (NESTs) are benefited over local teachers.

Other related aspects that have been problematized are the reasons why policies are created and the results out of them. As an example, in a study carried out in Turkey, Kucukoglu (2013) finds the creation of language policies that vary over time only to fit commercial,

geographical and religious purposes very problematic. Regarding the results, Altinyelken, Moorcroft and van der Draai (2014) indicate that the role played by language-in-education policies in Africa is the one of boosting inequalities in Africa’s education system.

purposes and are based on alien principles, for example, in the Common European Framework (2001) which was not designed to be implemented in Latino countries. Likewise, Guerrero (2010) points out at the idealistic images given to teachers and the unrealistic expectations of them, according to Colombian language policies.

Additionally, for some authors the problem relies on the ignorance of policies by the teachers who are compelled to carry them out. Ahmad and Kahn (2011) criticize the lack of awareness of language policies in English language teachers training programs in Pakistan, this creates that language teaching is not seen as an important component of education. In the same way, Trevor (2012) refers to the language used by instructors at the moment of communicating policies to the teachers as inadequate, which ends up affecting the practices of the teachers in and outside the classrooms.

A final aspect that has been pointed out by some authors is the conditions under which teachers have to follow the policies. Guerrero and Quintero (2013) problematize the challenges that teachers from public schools have to face in order to cope with school, students, parents and educational policies’ demands. Another study from Thomas, M., Thomas C., and Lefebvre (2014) find problematical the hard working conditions against the expectations of language policies of teachers in Zambia. Likewise, Mejia (2014) finds a mismatch between the actual practices of the teachers when contrasted with language policies in Colombia, It means that there is a discrepancy between what the teachers are commanded to do and what they are able to or willing to develop.

Statement of the problem

With support from the analysis of the three sources of information described above, my personal experience, a survey and the literature, since there is little research on teacher’s subjectivities and EL teachers as NNEST in Colombia, and that a few studies about language policies and NNESTs are narrative, I arrived to the conclusion that there is a need to document the configuration of subjectivities of EL teachers as NNESTs in relation to language policies in Colombia using a narrative approach.

The importance of the use of narratives both as a theory and as an instrument to collect data in research studies has been stressed out by several authors like Barkhuizen (2008), who asserts that “narrative inquiry in language teacher education aims to understand the experiences of teachers in the particular contexts in which they teach” (p372). The author refers to the role of narratives as a research tool that allows the researcher to comprehend particular experiences in certain contexts; for this study the context in which the participants are involved plays a very important role, it is located specifically in Colombia and in regards to the language policies implemented here. Certainly, narratives are socially, culturally and historically located,

Research question

The research question of this study was stated in order to reveal, through NNESTs’ narratives, the way they configure their subjectivities within the framework of language policies in Colombia. Configuration is understood as shaping something using different elements; in the case of subjectivities they are composed by different elements such as thoughts and emotions (Weedon, 1987), travels, memories, voices, aspirations, and experiences among others (Huergo, 2004).

The research question of this study was stated as: How do NNESTs configure their professional subjectivities in the frame of Colombian language policies?

Objectives

General objective.

To analyze the configuration of professional subjectivities of EL teachers as NNESTs in the frame of Colombian language policies.

Specific Objectives.

• To identify NNESTS self-reported practices which reflect their subjectivities. • To trace the process of the configuration of their subjectivities.

Rationale

As it was mentioned before, language policies in Colombia are designed without taking into account the possible contributions from the people directly involved in their implementation, that is, teachers. This research sought to interpret how EL teachers configured their subjectivities by reason of language policies, this way, the needs that these teachers have as subjects can be bear in mind by policies’ designers.

Through their narratives this study identifies and analyzes some self-reported pedagogical practices carried out, and traces how they have configured their professional subjectivities in order to understand how these teachers have offered their knowledge to education. Said knowledge can be a powerful input for the professionals involved in levels one and two of policy making, (Corder, 1973) so they should make well informed decisions and design language policies which are suited to the particular circumstances of Colombia. Accordingly, this research study has relevance in the local context because the results presented here can contribute to see education from a bottom-up perspective, that is, from the teachers to the technocrats, changing the traditional top-down perspective.

Additionally, the results from this study might be esteemed when designing teachers’ development programs. Gonzalez (2007) asserts that EL teachers’ development programs implemented in Colombia under policies such as Colombia Bilingue (Bilingual Colombia) are not adequate for the teachers’ reality and context. In this study the participants revealed their configuration of subjectivities by telling about their desires, aspirations and experiences; the people involved in teachers’ development programs design could consider this narratives and its interpretation, so such program responds to the real needs expressed by the participants.

literature since no study in Colombia has integrated subjectivities, NNESTs and NESTs dichotomy and language polices before. It can be an invitation for other scholars to deepen and expand in such issues.

CHAPTER II

STATE OF THE ART

Introduction

This research aims at describing the way Colombian EL teachers configure their

professional subjectivities in relation to language policies. In concordance to that objective this study relies on three main constructs: teachers’ subjectivities, NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy and language policies. I will show some studies that have reported results in each of the constructs.

Background to the study

Some studies about subjectivities.

results of this study valuable because they act as a frame to interpret the narratives of Colombian EL teachers in relation to language policies and the configuration of their subjectivities.

Keeping on the track of teachers’ subjectivities but in regards to teachers’ development, Greenwalt (2006) observed the way student teachers carried out videotaping tasks; he describes how their subjectivities as students changed into subjectivities as teachers. The purpose of his study is for teacher instructors “To think and rethink their own pedagogy and how it contributes to the creation of teacher subjectivities among student teachers.” (p. 399). The process that these student-teachers carried out to configure their subjectivities as teachers is meant to contribute to teacher trainers in helping students-teachers. Yet, it is also significant to understand the way those subjectivities are constructed.

help to describe a phenomenon, in case a paradigmatic analysis of the narrative data takes place. (Bolívar, 2002)

In a different approach, Ali, Turvey and Yandell (2012) listened to two teachers’ stories on how the standards-based reforms have an influence in students and teachers in England schools by deeply redesigning social relations and subjectivities. The study argues that these reforms failed to portray the complex realities of the classroom. It describes the way teacher’s and learners’ subjectivities and agency are continually “effaced by the dominant discourse, are continually being reasserted, continually threatening to undermine the false simplicities of the standards” (p. 26). This shows how external factors influence the configuration of subjectivities and, consequently the actions taken by the teacher and the learners.

What has been done in relation to NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy.

The second construct of this research study deals directly with the dichotomy between NESTs and NNETs, which has been a concern widely investigated worldwide. Although not many studies in this field have been developed in Colombia, there is a lot of information that can be found around the world.

To start, some of the studies have focused on the similarities and differences that students perceived when they are taught by NESTs and NNESTs. I will focus on three studies that were developed in different countries and yet produced similar results.

data indicated that NESTs display superior language proficiency, mainly on vocabulary grounds, whilst NNESTs revealed a better understanding of grammar structures. NNESTs stood out for their knowledge of the local language, a characteristic not often found in NESTs which can also be problematic for empathy with their students. Finally NESTs were criticized for not preparing their lessons, having a casual attitude or not following the course book, things that NNESTs usually do. The results from this study can be related to the ones in the following research.

The second study was carried out by Ma (2012) in Hong Kong. He interviewed students in order to report on their NESTs and NNESTs’ strengths and weaknesses. The investigator found linguistic, pedagogical and socio cultural strengths and weaknesses. In regards to the advantages found in NNESTs, from the study it can be reported, having better communication with students, understanding the local educational system and understanding student’s needs, difficulties and abilities as the key results. On the other hand, the main NNESTs’ difficulties were inadequacy in English proficiency, insufficient target cultural knowledge and less motivation for students to communicate in English. In reference to NESTs, the leading strengths described were, good English proficiency, knowledge of target culture and provision of English environment. In contrast, the identified weaknesses were difficulties in communication with students, cultural barriers with students and difficulties in understanding student’s needs.

content of the courses. In contrast NNESTs were perceived as communicative and being more empathic with students, as well as, better at teaching grammar. The study finishes by recommending the instructors in pre-service courses to make more emphasis on the cultural aspect in order to give more tools to NNESTs.

The studies summarized before dealt with the comparison between NESTs and NNESTs, yet, other researchers have focused on the employability and status given to each group of teachers.

Firstly, Clark and Paran (2007) informed about the preferences of the people in charge of recruitment in different schools and universities in the UK. The authors wanted to extend a previous study which was developed in the United Stated in order to contrast the information of that study with the situation in the UK. The study outcome exposed that for the vast majority of the employers (72.3 %) who answered the questionnaire, being a NNEST was moderately important and very important. Teachers from the United States and Australia were the most desirable, whilst teachers from countries in South America, Asia and the Baltics were the least wanted. This study seems to confirm the preference given to NESTs over NNESTs when applying for a job.

preference is not clear and, in fact, they tend to feel warmer towards NNESTs. The results from this study match the ones from the next research, although it was developed in a different country.

Diaz (2015) carried out an investigation about the preferences of French university students towards NESTs and NNESTs. 78 students answered a survey and the general results showed a tendency to prefer NESTs, yet, when analyzed in detail, this preference is not clear. For instance, NNESTs are preferred in freshman years, and they are favored to teach grammar.

It could be concluded from the results presented in the three studies above that it seems to be a preference for NESTs, which is stronger when it comes to employers, but not so clear from the students’ point of view. What is more, the results of these studies are in concordance to the original concern that motivated the present research which was the feeling of discrimination that I experienced when working in different places such schools and institutions.

To conclude, although research on the NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy has spread out, Hayes (2009) claims that there is a need to focus on NNESTs experiences, needs and constrains, not only because are they now the majority of the EL teachers, but also because their contributions are valuable. Hence, in a study he carried out with NNESTs in Thailand he reported on the classroom methods and commitment to teaching that the participants displayed when telling their experiences.

participants shaped their professional identities in order to face the challenges provided by a globalized ELT world.

Summarizing, I have reported studies which approach the NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy from different points of view, one comparing these two groups of teachers, another, evaluating the advantages or disadvantages that they might face, and finally, reporting on studies that give prevalence to NNESTs claiming their importance. In the next section I will refer to the last theoretical concept of this study: language policies.

Language policies: a widely researched topic.

About the third and last construct, extensive research has been published about educational policies both in Colombia and in other countries. The results of these studies show that there is a strong tendency to take a critical point of view towards the design, implementation and results of educational and language policies.

In the same direction, Usma (2009) analyses and describes how the National Program of Bilingualism, among other language policies, externalizes policy discourses, instrumentalizes languages, stratifies groups, languages and cultures, and standardizes and markets foreign languages. In addition, concerning the role given to English in Colombian national languages policies, Guerrero and Quintero (2009) claim that English is treated as a neutral language in official documents and explain this neutrality by outlining three categories: prescription, denotation, and uniformity. The criticism towards this treatment of English relies on the fact that it is presented in a way that is disconnected from the real contexts of language, students and teachers, a fact that places them in an alien environment and ends up hindering the learning of English.

When it comes to teacher development, Correa and Usma (2013) refer to the policies promoted to improve the language proficiency of EL teachers, specifically in the document “Program for Strengthening the Development of Competencies in a Foreign Language” they assert how this program is intended to “fit a bureaucratic policies making model” (p. 226) which has been questioned, therefore, they proposed a new model that includes the participation of the stakeholders.

perception presented in the news and other media about EL teachers lacking the linguistic and strategic skills to appropriately teach the language.

Additionally, Mejia (2012) critiques the emphasis put on being bilingual as the key to have better life opportunities, even though there is no valid proof that bilingual people in Colombia have better working opportunities or that companies consider being bilingual an imperative, a lot of pressure is imposed on students and teachers shoulders to fit policies which objectives are based on that belief. A good example of this view are the objectives in the Colombian National Standards (CNS) which keep repeating the importance of learning English as a necessary skill for a globalized world. For instance, in the CNS’s there is a section entitled “Reasons to learn English” in which bilingualism is immediately reduced to “English”, as well, in this section one of the reasons is “To have access to scholarships and internships in other countries”, ignoring that these opportunities are not only given in English speaking countries. Another reasons says “[learning English] offers more and better working opportunities”, and as mentioned before, there is not real evidence of this happening.

images given to EL teachers in educational policies so she establishes that EL teachers have three main representations. First, teachers are invisible, because they don’t participate in the creation of policies. Second, teachers are clerks, expected to deliver a product diligently without questioning or interfering. And thirdly, teachers are technicians or marketers meant to create and “sell” a product. My study deepens on the construction of subjectivities, that is a new focus, different from the ones related to identities and images of teachers, in fact, through the narratives the results from the previous studies could be reinforced or take a new course.

Finally, directing the attention to EL teachers’ in-class practices and experiences, Mejia, et. al. (2014) carried out a study in Bogotá and Armenia on empowering teachers to understand the link between their pedagogical practices and the language policies proposed in the National Bilingualism Project by reflecting on their practices and implementing collaborative innovations. As a result, the authors reported a better understanding of shared responsibilities on generating teaching and learning authentic processes. I found that these results were a starting point to explore in EL teachers’ narratives, the way they configure their subjectivities, understanding to what extent they are molded by policies or they transform them in a beneficial way.

critical view to the continuous changes in Turkey’s language policies. These changes are not much different from the ones in Colombia, fact that proves and exemplifies the problems that arise from language policies that are based on mistaken beliefs often imposed by the market.

An additional concern regards to the conditions in which the teachers are constrained to carry out the policies. Thomas and Lefebvre (2014) described the difficult conditions that EL teachers in Zambia have to face in their daily practices. These problems are related to overcrowded classrooms, lack of materials and facilities, inexistent training for teachers, and generally speaking, mismatches between the educational polices and the realities that the teachers have to overcome daily. An important finding is the fact that although courses must be taught in English, when the teachers go to rural areas, the students don’t speak English, consequently the educators have to learn and teach in the local language at the same time. Nevertheless all these issues, a strong commitment to the profession was reported by the interviewed teachers. Therefore, I can conclude that they resist in many ways what is imposed to them, managing to have a voice when they have been put aside, like in the creation of language policies.

secondary instruction, which is given in English. No matter the difficulties, the results listed above are really remarkable because they illustrate the support that the mother tongue can give to the learning of a foreign language, as several studies have pointed out (Devereaux, Wheeler and Fink, 2012; Obaidullah, 2016; Shahnaz, 2015; Then and Ting, 2009).

From a different point of view, integrating the NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy and language policies, Wang and Lin (2013) in a comparative study on how the recruitment and language policies portray professionalism of NESTs in Hong Kong, Korea, Japan and Taiwan, found that these policies follow “native speaker norms” (p. 5) approach that, as a consequence, legitimizes unqualified and inexpert NESTs. As a result these policies have produced the opposite purpose to improve English language teaching by damaging the quality of the instruction and affecting the professional identity of the local NNESTs.

The second study was carried out in Pakistan. Ahmad and Kahn (2011) developed a study about the significance of the awareness about language policies and teachers practices. They concluded that the lack of instruction about language policies in English teaching programs led to poorer resources in ELT. Hence, they recommend including such an instruction in the teacher’s training and development curriculum. These results can be contrasted and complemented to the ones in my study because they expand by adding the concept of the construction of subjectivities.

As can be seen from the results presented in the previous studies, language polices tend to disfigure the concept of bilingualism. They are the basis for the creation and implementation of teacher development programs that do not reflect the real needs of the teachers and the students. Also, they are based on unproved or unrealistic objectives which segregates certain communities, and ends up affecting both the teachers and the students in their learning process.

CHAPTER III

LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction

Taking into account the three constructs which guide this research study, in this chapter I will explain the theories and concepts that support this investigation by giving the

definitions found in the literature and my interpretation of them. Finally, I will draw some conclusions to show the relation between the configuration of subjectivities, NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy, language policies, and indicate the contribution of my research.

Theoretical framework

This research study is grounded in the poststructuralist paradigm. Hatch (2002) explains in detail what these kind of studies stand for. First, when describing the ontology he says that these studies reject the conception of order because “Order is created in the mind of individuals” (p.18) who needs to give meaning to the events surrounding them. Second, regarding the

epistemology, Hatch explicates how poststructuralist studies are meant to deconstruct the universal idea of truth; he asserts that “For poststructuralists, multiple truths exist, and these are always local, subjective and in flux.” (p.18). Third, in relation to the methodology,

poststructuralist studies follow some of the methods of other quantitative studies but the focus they gave to data is different as they understand it “as texts that represent one or many stories that could be told”, therefore life has three aspects: lived, experienced and told. This is closely linked to the type of study selected, which is a narrative one.

“Deconstructivists produce analysis that reveal the internal incongruities of discourses and expose the consequences of action taken based on the assumed truthfulness of those discourses.” (p.19). While researchers that work on genealogical fields create “Critiques that reveal historical ruptures that challenge the foundations of modern structures, institutions and discourses.”(p.19). Last but not least, some poststructuralist researches breed research accounts that include

numerous voices which are situated in a “specific, local, situational, partial, and temporary nature of the stories being told” (p.19).

The present research study accounts for the last product described, since it regards the personal stories of EL teachers located in a specific moment and context, and, in reference to a particular situation, that is, the influence of language educational policies in the construction of their subjectivities.

In addition, Baxter (2008) lists the principles of poststructuralist studies as “Complexity, plurality, ambiguity, connection, recognition, diversity, textual playfulness, functionality, and transformation.” (p. 245). The way these principles are present in my research comes from the understanding of the different elements that are included in a narrative, where the order, accuracy or details of the events told are entirely the speaker’s decision, so, when analyzing the data I considered the principles mentioned above.

In the next section, considering the main constructs of my research study which are

teachers’ subjectivities, NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy, and language policies, I will explain the theories and concepts that support each of them.

A theoretical approximation to subjectivities.

conscious and unconscious thoughts and emotions of the individual, her sense of herself, and her ways of understanding her relation to the world” (p. 32). That is, subjectivities are constructed by the individual when taking different elements present in the environment and giving an

interpretation to them. The authors’ definition catches my attention since she mentions that not all the thoughts are conscious, consequently subjectivities are configured both consciously and unconsciously, it means, the environment plays a role that the subject cannot avoid. That is why in this study it was found that although some policies were not explicitly clear in the participants’ minds, they could not bypass being influenced by them.

The individual nature of the configuration of subjectivities was also corroborated by Moje (2014) who affirms that “subjectivities are the stories we tell to ourselves, about ourselves” (p. 595). In this sense, she insists on the private and biased nature of subjectivities, which is a characteristic of post-structuralist studies. Additionally, in her definition Moje refers to the continuous re-configuration of the self by making an interesting analogy with narratives, for her, subjectivities are equal to narratives, this interpretation connects to one of the characteristics of narratives, which is to give meaning to the experiences lived. Gonzalez (2011) asserts that “it is through narrative that we represent and restructure our world in our daily lives” (p.89). This definition of narratives matches the definition of subjectivities given by Moje where the role of the individual is confirmed with terms such as “our” and “ourselves”.

meaning and values.” (p. 8). This way, the authors recognize that subjectivities are influenced by the environment and are created and configured taken already existing elements.

When trying to explain how subjectivities are constructed, Greenwalk (2008) states that, from Foucault’s point of view, subjectivities are produced when we place ourselves at any part of a power as a network of relationships. Social beings are involved in a structure where other subjects with their cultural background, ways of thinking, ways of acting, and many other factors both social and cultural, intersect with them. Each subject plays a role of power or subservience, but such role is not fixed, at times the subject claims the power and at times he surrenders to the power of others, when doing this, subjectivities are conformed, it is the decision on how to act or think towards others what configures the subjectivity.

Since subjectivity is both thinking and acting, Meguins and Carneiro (2015) uphold that objectivity and subjectivity are closely linked and cannot be easily separated; they say that “objectivity and subjectivity are both constituent and constituted by men. Their activity changes the external and inner nature, displaying in them an identity by which they recognize themselves while they are also recognized in the same way. Humans are materialized upon their actions.” (p. 3455). What is interesting about this definition is that no matter how personal subjectivities are, they come to life in the actions of the subject, they are reflected in the activities that the

individual performs, therefore, they become objective. Narratives, as an instrument that allows to reflect upon previous actions (Barkhuizen, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011; Guerrero, 2011), provide an opportunity for the researcher to spot the configuration of the subjectivities. By telling about experiences which involve the actions performed by the subjects, they display their subjectivities.

subjects are constituted in their knowledge which is acquired and renewed through their lives; such knowledge can be academic or experiential and it comes from the interaction with others and with the contexts in which the subjects are immersed, so, in their social practices the subjects will be either exhibiting or acquiring knowledge. Secondly, when the subjects interact with others there are issues of power that continuously arise and this power, as mentioned before, is not static but movable: one subject can hold the power at a moment and later this power can be resisted by the people it is directed to. Such resistance empowers the other part which later will take actions to display it. Finally, subjectivities as a reflection of the way we understand

ourselves are expressed in social practices. This practices might vary depending on the context where the subject is immersed; when explaining Foucault’s vision of subjectivities Kelly (2013) asserts that subjectivities are “not a matter simply of thought determining our being, but of a self-understanding that is connected to more concrete practices” (p. 515), hence, subjectivities are multiple and have several manifestations according to the contexts where the subject interacts.

From the definitions and insides presented above I have interpreted subjectivities as the particular way a subject senses, sees and experiences the world when interacting with others and the contexts he is immersed in. This particular vision is the profound reflection about the

understanding of oneself which is later revealed in the way of thinking, being and acting in concordance to what is believed at certain moments or places; since such moments and places are varied, so subjectivities are. This is the understanding that I used as a guide when analyzing and reporting the findings of the study.

The controversial issue of NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy.

The dichotomy which involves NESTs and NNESTs has been approached and defined by several authors and has inspired many research studies.

In general terms this dichotomy could be defined as the preference given to NESTs since they are “considered to be the best model and type of language teacher for non-native speakers to follow” Shibata (2010, p. 125), and “the model speaker and the ideal teacher” Clark and Paran (2007, p. 407). This preference has its foundation on the belief that NESTs overpass their non- native counter parts in terms of oral skills, namely vocabulary, pronunciation and cultural knowledge (Arva and Medgyes, 2000; Clark and Paran, 2007, Diaz 2015). Furthermore, the advantages of NNESTs have been pointed out by the same and other researchers. For instance, Hayes (2009) makes emphasis on the method and the compromise showed by NNESTs in their classrooms. Arva and Medgyes (2000) and Cakir and Demir (2013) highlight the knowledge of the local language and the grammatical and pedagogical knowledge as characteristics that most of the NNESTs own.

concepts that he named “genetic nativeness” and “functional nativeness”. In the first case a person is a “genetic native” if he was born in Australia, Canada, the USA or the UK, what he calls the Inner Circle countries. In contrast, a person could be a “functional native” if he was born in an Outer Circle country; where English is the second language, for example India or

Singapore. People who were born in other countries would be non-native. Yet, this is just an example, because historically scholars cannot be able to come to an agreed definition, as Paikeday (1985) recognizes, this is a term that cannot be closely defined, in fact, Davies (1991) argues that belonging to a native or non-native category is an issue of self-recognition. This concept of “nativeness” has been addressed by some Colombian policies when they equal “native” to “foreign”. It seems that for policy makers having English speakers from abroad is enough to call them native, and so, pretend to add a sense of “status” to their programs. (e.g. Programa de Formadores Nativos- Native Trainers Program )

Additionally, Ma (2012) claims that the idealization of the NESTs as “fully competent users of their language” (p.2) is problematic. He asserts that “native speakers of a language may not possess all the knowledge about the language they speak.” (p.2). In the same sense, Phillipson (1992) used the term “native speaker fallacy” to refer to this idealization. The author said that the advantages that are usually assigned to NESTs can be taught to NNESTs which will eliminate the supposedly superiority. In fact, for some of the participants in this study such differences were not relevant and their subjectivities have been molded so they do not consider themselves inferior, as well as, other participants felt they are continually learning from their native counterparts, mostly regarding vocabulary and pronunciation.

speaking it, so, having a native as a model is no longer necessary. Second, with many studies making emphasis on the strengths and weaknesses of both NESTs and NNESTs, they are considered different but not superior or inferior. And finally, other aspects such as, expertise, commitment and disposition to progress are now more relevant than the plain capacity to use the language.

To expand on Todd and Pojanapunya’s (2009) claim on the increasing consideration of English as an international language, it is valuable to mention that such nomination has its roots in two main factors; the number of people in different countries who currently speak or are learning to speak English and the uses given to the interaction in this language. Hu (2012) reports that the number of native speakers has been exceeded by non-native speakers; as well, Schneider (2011) calculated that 2 billion people were English speakers at the moment of his study.

Furthermore, the fields of usage cover politic, cultural, social, educational, economic and intellectual areas (Kachru, 2011).

describe by Brutt-Griffler and consequently can be called an International Language as Todd and Pojanapunya’s (2009) assert.

However, although research supports that there are more NNESTs than NESTs (Cakir and Demir, 2013; Guerrero and Meadows, 2015; Ma, 2012) some authors still maintain that the NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy is valid and applied usually by employers. For instance Clark and Paran, (2007) and Todd and Pojanapunya (2009) affirm that no matter the efforts to give equal treatment to NNESTs, and what is presented in the literature, preference continued being given to NESTs.

From the previous definitions and conflicted concepts it can be stated that although for many scholars and teachers the NESTs and NNESTs dichotomy is a conception in conflict, from the results of different studies, including the present, such dichotomy can still be perceived and has an effect in both teachers and students, even more when they are influenced by policies, programs and educational models.

Language policies: from theory to reality.

Regarding the last theoretical concept of my study, there seems to be an incongruity between the definition, the planning and implementation, and the objective of language policies. For instance, Carson (1990) defines national language policy as “A set of nationally agreed principles which enable decisions makers to make choices about language issues in a rational, comprehensive and balanced way” (p.150). Additionally, she defines language policy as “a set of principles agreed on by stakeholders, enabling decision making about language and literacy issues in the formal education system at all levels: early childhood, primary, secondary and the teachers education segment of the tertiary level” (p.150). Yet, from these definitions, the

fact, several authors conflict that the stakeholders can participate in such decisions. (Cárdenas, Chaves and Hernández, 2015; de Mejía, 2006; González, 2007; Miranda y Echeverry, 2011; Sánchez y Obando, 2008; Usma, 2009)

Moving to a formal definition that relates to the reality identified in this study, Djite (1994) in Kucukoglu (2013) mentions that language polices “are the deliberate choices made by governments or other authorities with regard to the relation between language and social life” (p. 63). I consider that these authors’ definition is more in concordance to the situation faced in Colombia and many parts of the world. This also links to the description given by Phillipson and Skutnabb-Kangas (1996) who say that “language policy is a broad overarching term for decisions on rights and access to languages and on the roles and functions of particular languages and varieties of language in a given polity.” (p. 434). These authors focus on the practical meaning of language policies, but there are other dimensions to be considered.

Concerning the creation and implementation of language polices, Corder (1973) asserts that the decisions about language policies are made in three levels, the first one is political, the second involves linguistic and sociolinguistic experts, and in the third level we find the teachers. In the same direction, Medgyes and Nikolov (2005) mention five levels or participants in the creation of language policies, they are: policymakers, for example, politicians, ministry officials, etc.; specialists, such as curriculum designers, materials writers, among others; teachers,

students, and mediators, for instance, institutes, agencies, councils and organizations. The authors assert that all the participants in each level are meant to participate but in reality teachers’, and even more, students’ voices are hardly ever, or never, heard.

policymakers consider valuable, whilst the second refers to “The regulations at state and substate level that specify the implementation of language policy”. (p. 435). Usually, in both, language planning and legislation there is no participation of the people who will be directly affected by those polices. Being excluded from language planning and legislation helps to shape the

subjectivities of the teachers they reflect on their role and act accordingly. As a consequence they might reject what is imposed or accept it as a situation that cannot be changed.

To finish, Godenzzi (2003) denotes the objective of language policies, which is “To facilitate the development of the speakers as full human beings, able to express themselves, to interpret the world, and to create meaning and beauty” (p. 294). Even though that is the ideal objective, in reality, language policies tend to respond to economical and market demands rather than to fulfill the aesthetic and communicational goal of a language.

To conclude, language policies can be approached from different directions, its formal definition, the role of the people involved in their creation, the stages on their conception and application, and the imagined objective. All these dimensions play a role in the configuration of EL teachers’ subjectivities, either because they have been consciously studied by them or for there is a common knowledge about them, as it emerged in their stories.

The role of narratives.

Even though narratives are not a theoretical construct in this study, they are an important part of it, and this is the reason why I would like to define and interpret them as an introduction for the next chapter.

that we use to construct and express meaning in our daily lives” (p. 89). Since subjectivities are individual and closely involved to personal interpretation, narratives become a useful tool to disentangle them.

Making a differentiation, Cresswell (2007) explains the nature of narrative studies and points out at the differences between narrative studies as a methodology, which is, as an instrument to collect data and narrative as the phenomenon under study. When describing the characteristics of a narrative study, he says that narratives are stories that “Tell of individuals experiences and they might shed light on the identities of individuals and how they see

themselves” (p. 71). In this research narratives were used as an instrument to collect and interpret data rather than a phenomenon to be described.

Finally, Elliot (2005) asserts that “A narrative conveys the meaning of events” (p.3). She gives three characteristics that a narrative should meet, those are: to be chronological, to have meaning, and to be social. However, these characteristics do not follow any specific pattern since they rely on the speakers’ decisions made at the moment of narrating. When analyzing the data, these elements were of paramount importance as can be seen in chapter four.

To conclude, I can summarize that narratives help individuals to give meaning to the events in their lives by retelling what happened. This function of giving meaning suits the purpose of describing the configuration of subjectivities that this study accounts for.

Conclusion

which, as mention by Foucault, are shaped by power issues like educational and language policies. The theories and concepts explained in this chapter were the starting point on the construction of new knowledge about the relation of EL teachers’ subjectivities configuration as NNESTs and language policies.

I want to exemplify my understanding of the theory involved in this study using figure 1. In the broader rectangle I see poststructuralism as the concept that embraces the theory of my study. The three main concepts are represented by circles which intersected each other leaving space at the central intersection for the contribution that my study could provide. These three constructs are contained in the concept of narratives since they are the vehicle through which they will be expressed.

CHAPTER IV

RESEARCH DESIGN

Introduction

From my personal experience, using literature, and a survey, I could identify the

problematic situation which this research study is based on. Accordingly, the problem is the need to document the configuration of subjectivities of EL teachers as NNESTs in relation to language policies in Colombia. This need corresponds to the fact that there is little research on teacher’s subjectivities and EL teachers as NNEST in Colombia; moreover, just a few studies about language policies and NNESTs are narrative ones.

After identifying the problem I stated the research questions: how do non-native NNESTs configure their professional subjectivities in the frame of Colombian language policies? Furthermore, the main objective of my study is to analyze the relation between the configuration of subjectivities of EL teachers as NNESTs and language policies in Colombia through their narratives. This main objective is also supported by two specific ones. Firstly, to identify the participants’ self-reported practices which reflect their subjectivities; secondly, to trace the process of the configuration of their subjectivities; and finally, to identify the policies that were valid at the moment the stories communicated by the participants took place.

Type of study

The most suitable type of study that fitted my purposes was qualitative. This line of thought in regards to the research is based on the understanding, description and construction of meaning, according to Hatch (2002) “Qualitative Research seeks to understand the world from the perspectives of those living in it” (p.7) Also, Savenge and Robinson (2004) claim that

qualitative research is a “research devoted to developing an understanding of human systems” (p. 1046). In addition, Yin (2011) points out at five characteristics of qualitative research that are included in my research study, these are: the meaning of people’s lives, the views and

perspectives of the participants, the contexts where these people live, the contribution to existing concepts or the creation of new ones to explain human social behavior, and finally, the use of diverse sources of evidence. These five characteristics are integrated in the present research.

Narratives.

Through this research design I meant to account for the configuration of EL teachers subjectivities in relation to Colombian language policies from their perspective as NNESTs. To do so, I decided to use narratives and the subsequent analysis of them. Narratives are adequate for its potential contribution in reporting people’s experiences and their interpretations, as well as, portraying identities.

when using a grounded theory approach (Charmaz, 2006; Hubbard and Miller, 1993; Strauss and Corbin, 1990) which is organizing the data and coding it into categories.

Also, there is the narrative thought. This type of thought is characteristic (but not limited to) poets and writers, among others. When using the narrative thought the authors prefer to express their art and explore the world so it produces stories. No thesis is being tested; hence, there is a lot of space for interpretation from the person who reads the stories produced. Bruner claims that this kind of thought is used to tell what happened and the way the author experienced it. Ricoeur (2006) explains the same concept by adding that a narrative has an element of

intelligibility that allows the reader to understand the story.

Another recognized author who defined narrative was Labov (1998), who says that “narratives are a method to recapitulate past experiences pairing a sequent of verbal clauses with a sequence of events that (as it refers) actually happened” (p.10). Labov’s characterization refers to the structural dimension of narratives without forgetting the experiential component of them; this can be linked to Barkhuizen and Wette’s (2008) definition of narratives when they call them “stories of experience” (p. 373). But apart from the plain definition, narratives can have different purposes; one of them is to research.

The use of narratives as a method to investigate is called Narrative Inquiry. Barkhuizen and Wette (2008) point out at the objective of narrative inquiry as “understand the experiences of teachers in the particular contexts in which they teach.” (p. 372). The use of narratives in research studies allows participants to make meaning of their experiences by reflecting on them, so the authors claim “When teachers share their stories with collaborating researchers they display both their lived experiences and their understandings of these.” (p. 374).

experience is mediated by story.” (p.221). For the authors, narrative is both a phenomenon and a method, “Narrative is the phenomenon of inquiry because everything, […], is a phenomenon narrated through stories. The phenomena of narrative inquiry are, themselves, narrative in nature” (p.221).

This study focuses on the vision of narrative as a method to collect and analyze the data in which different elements converge. Connelly and Clandinin (2005) state that if we are interested in using narrative inquiry to study EL teachers we have to learn how to think narratively, this way, narratives are developed in an ongoing life space. This life space has 3 main dimensions: Temporal, personal-social, and place. (See figure 2.)

Furthermore, Barkhuizen (2007) identifies eight dimensions for narrative research. He establishes that these dimensions are correlated and have a space in three levels as can be seen in figure 3.

Figure 3.Dimensions of Narrative Research. Adapted from Barkhuizen (2007)