The Relation between Learning Styles

according to the Whole Brain Model and

Emotional Intelligence: A Study of University

Students

Relación entre los estilos de aprendizaje según

el Modelo de Cerebro Total y la inteligencia

emocional: un estudio en estudiantes

universitarios

MARTA ESTRADA

Universitat Jaume I estrada@emp.uji.es

https://orcid.org/000-0002-3644-4514

DIEGO MONFERRER

Universitat Jaume I dmonferr@emp.uji.es

https://orcid.org/000-0001-7996-1151

MIGUEL-ÁNGEL MOLINER

Universitat Jaume I amoliner@emp.uji.es

https://orcid.org/000-0001-9274-4151

Resumen: Durante las últimas décadas ha existido un profundo interés en la literatura por ahondar en los estilos de aprendizaje a fi n de desarrollar las me-todologías más efi caces en el proceso de enseñanza/ aprendizaje. Sin embargo, pocos estudios han anali-zado la relación existente entre los estilos de aprendi-zaje según el Modelo de Cerebro Total y la inteligencia emocional en alumnos universitarios, que es esta la propuesta implícita en este trabajo. Metodología: Para la medición de los estilos de aprendizaje dominantes se utiliza el Diagnóstico Teoría de Cerebro Total, que es una adaptación reducida del instrumento de medida Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument. En relación a la medición de la inteligencia emocional se utiliza una adaptación simplifi cada de la versión castellana

del Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Resultados: Los estilos de aprendizaje basados en dominancias mixtas infl uyen de forma positiva en el desarrollo de la inteligencia emocional. Por otro lado, se observa una contribu-ción más pronunciada de los estilos de aprendizaje asociados al hemisferio derecho en el desarrollo de la inteligencia emocional. Conclusiones: Existe una necesidad de entrenar a los estudiantes en el uso de un estilo de aprendizaje que permita el uso de domi-nancias mixtas, para contribuir así al desarrollo de su inteligencia emocional.

INTRODUCTION

O

ne of the aims of the teaching-learning process is to give individuals the skills with which to interpret phenomena and events in their environment, thereby preparing citizens who will contribute to developing healthy and effi cient societies. Intrinsic to the achievement of this goal is the preparation of autonomous professionals who are able to construct their own personal learning systems. This process involves strengthening intellectual skills, which include ana-lytical intelligence, but also the social and emotional skills more closely related to emotional intelligence (henceforth EI). In recent years a growing body of research has shown the importance of training abilities related to the socialisation process, acquiring the competencies or skills related to this process, solidarity, tolerance, empathy, and self-esteem (Estrada, Monferrer and Moliner, 2016; Durlak, Weiss-berg, Dymnicki, Taylor and Schellinger, 2011). All these skills have an inevitable impact on an individual’s personal and social development. In this regard, the busi-ness community is increasingly calling for universities to develop their graduates’ EI, thus preparing them to successfully adapt to the world of work (González-Arias and Alucema, 2015). In responding to this concern, it is important to consider not only educational content, but also emotional education in its broadest sense. The development of professional competencies can only be guaranteed if the teach-ing-learning process also includes students’ personal development (Rosa, Riberas, Navarro and Vilar, 2015); from the educators’ perspective, therefore, the process requires an understanding of the learning styles students use. This understanding will help educators to effectively design the necessary strategies and methodologies for students to develop their knowledge and learning to the full.Recent decades have seen a growing interest in the study of mental capaci-ties that allow individuals to construct their own knowledge and learn how to face Abstract: There has been considerable academic

interest in learning styles in recent decades aimed at developing more effi cient methodologies in the teaching-learning process. However, few studies have analysed the existing relationship between learning styles according to the whole brain model and emo-tional intelligence in university students, the proposal of the present research. Methodology: Dominant learning styles were measured with the Whole Brain Theory Diagnosis, a shortened adaptation of the Her-rmann Brain Dominance Instrument. Emotional intel-ligence was measured using a simplifi ed adaptation

of the Spanish version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Results: Learning styles based on mixed dominances positively infl uence the development of emotional intelligence. Learning styles associated with the right hemisphere were also found to have a greater impact on emotional intelligence. Conclusions: Students should be trained in a learning style that enables the use of mixed dominances, thereby contributing to the development of their emotional intelligence.

life situations effectively (Estrada, Monferrer and Moliner, 2016); Gómez, 2004; Perea, 2011; Segarra, Estrada and Monferrer, 2015). In this vein, Alonso, Domingo and Honey (1994) defi ne learning styles as, “cognitive, affective and physiological traits that serve as relatively stable indicators of how students perceive interac-tions and respond to their learning environments”. The concept of learning style is based on the unquestionable fact that everyone is different. This difference mani-fests itself in many forms and is refl ected in traits such as age, experience, level of knowledge and interests, and the psychological, physiological, somatic and spirit-ual characteristics that shape each individspirit-ual’s personality. Learning style is related to knowing (how do I know?), thinking (how do I think?), affect (how do I feel and react?) and behaving (how do I act?). The wide variety of cognitive and affec-tive elements intervening in the process means that each individual uses their own strategy for learning (Brookfi eld, 1995; Gómez, Oviedo, Gómez and López, 2011; Mallart, 2000). Defi ning all these theories on learning styles is an arduous task and the subject of some debate (Rojas, Salas and Jiménez, 2006). In the present study, rather than dwelling on these discussions we briefl y describe the main theories in the literature before proposing a theoretical model that, based on the whole brain model, associates different learning styles with the development of EI in university students. The fi nal objective of this study is to refl ect on how to effectively culti-vate and develop students’ emotional intelligence in order to best prepare them for their future professional careers. To this end, we fi rst introduce the theoretical frame undergirding this literature, defi ning the concepts of the whole brain model and emotional intelligence. Secondly, we propose the theoretical model that forms the basis for this study. We then present the methodology used for a sample of 853 university students enrolled on eight different degree courses, followed by an analysis of the results. The article ends with the study’s conclusions and limitations, and a discussion of its implications for educators.

THE WHOLE BRAIN MODEL

explain them as cognitive processes. Emotions are thoughts about the situations in which we fi nd ourselves and do not differ from cognitive acts. In sum, feelings and emotions are the way we explain emotionally ambiguous physical states to ourselves, using thought and attributions on the external and internal causes of this state. Emotions are the result of a cognitive interpretation of situations. One of the prime objectives of modern science is to locate these functions in the brain, as this information is essential to knowing how they work and how to activate them in the learning process. In what follows we provide a brief historical review of the predominant theories in the literature on the study of the brain and learning.

Sperry’s (1961) pioneering research on the theory of left brain-right brain dominance prompted other work on learning styles such as the theory of the tri-une brain, the whole brain model, multiple intelligences, emotional intelligence, among others. These theories refer to the brain’s anatomical and physiological composition in various structures that give individuals this integral character and allow them to see, feel, act, learn and live together, going beyond the capacities associated with obtaining information and taking decisions (Casado, Llamas and López, 2015).

Sperry’s (1961) theory establishes that the two brain hemispheres control dif-ferent types of thoughts, depending on which one each person prioritises. Thus, someone who uses the left part of the brain is more logical, analytical and objective, whereas those using the right side of the brain are more intuitive, refl ective and subjective.

Some years later, the triune brain hypothesis (MacLean, 1990) argued that the brain has three structures. The fi rst is the neocortex, consisting of the left and right hemispheres, the former associated with logical reasoning processes and breaking down a whole into its parts, and the latter concerned with the ability to see things holistically and establish spatial relationships. The second, the limbic system, is where emotional and basic motivational processes take place. Finally, the reptil-ian brain is where the processes controlling the routines and customs of human behaviour take place. Using these brain structures together allows people to take advantage of all their capacities in developing their learning.

in-dividuals with this brain dominance learn rationally and logically. The lower left lobe (quadrant B) is associated with sequential and planned thought; individuals with this dominance prefer organisation and routine. The lower right lobe (quad-rant C) is related to emotional, communicative and humanistic thought; subjects with this brain dominance learn by conceptualising and integrating. Finally, the upper right lobe (quadrant D) is associated with conceptual, holistic-intuitive and creative thought; subjects with this brain dominance learn by listening and asking questions (Flores and Maureira, 2015; Gardié, 1998; Gómez, Oviedo, Gómez and López, 2011; Velásquez, Remolina and Calle, 2007). Each individual tends to use the functions of one hemisphere more than the other –brain dominance– to inter-act with their environment (Herrmann and Herrmann-Nehdi, 2015; Said, Díaz, Chiapello and Espindola, 2010; Salas, Santos and Parra, 2004; Sánchez, 2010). This preference affects personality, skills and learning style, which led Herrmann to postulate that brain dominance is related to the way we prefer to learn, under-stand and express something (Rojas et al., 2006). Based on this idea, Herrmann devised the Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument (HBDI) to determine each per-son’s characteristic dominance profi le. This instrument establishes four learning style modalities: 1) realistic, belonging to the left hemisphere (quadrants A and B); 2) idealistic, belonging to the right hemisphere (quadrants C and D); 3) prag-matic (quadrants A and D); and instinctive (quadrants B and C) (Herrmann and Herrmann-Nehdi, 2015; Flores and Maureira, 2015; Maureira, Aravena, Gálvez and Cea, 2014; Segarra, Estrada and Monferrer, 2015).

These modalities imply a preferred way of knowing, which is the one an indi-vidual is most likely to use when resolving a problem or selecting a learning experi-ence. The way a challenge is met will vary according to whether it is approached from the left brain (or logical hemisphere), concerned with the details, parts and processes of language and linear analysis, or from the right brain (or gestalt hemi-sphere), dealing with images, rhythm, emotion and intuition, to synthesise all parts within an intuitive sense of the whole. The preferred way of knowing is therefore strongly related to what we prefer to learn and how we prefer to learn it. In sum, it is each person’s preferred approach to thinking emotionally, analytically, structurally or strategically, and according to the model proposed in this study, this predicts the way individuals manage the emotions they experience during the learning process.

EMOTIONALINTELLIGENCE

proposed by Hilgard (1980) and frequently used as a model for classifying person-ality. In this tripartite division, emotions are one of the three basic operations of the brain, together with cognition and motivation. Cognition (what I know) allows a mental representation of reality; motivation (what I want) activates and guides behaviour; and emotion (what I feel) encompasses the subjective experience of the activation, its meaning and its behavioural expression. Although these operations are understood to be different, it is recognised that they are related to and con-stantly interact with each other, penetrating cognitive processes and the acquisi-tion of knowledge (LeDoux, 2002). However, they have tradiacquisi-tionally been studied as separate and even confl icting aspects (Salomon, 1993). This is the case of the cognitive revolution in the second half of the twentieth century, which marked the beginning of a new stage in which the infl uence between cognition and emotion was established. Emotion was shown to affect cognition, as illustrated by the fi nd-ings of cognitive research in the 1980s and 1990s (Blaney, 1986); this was furthered by advances in the fi eld of neuroscience on the value emotional response adds to decision making and learning (Damasio, 2006).

In addition to the above, the concept of intelligence became more fl exible (Gardner, 1993; Guilford, 1985), practical intelligence was posited (Sternberg, 1985) and the general capacity to learn and adapt to the environment in a fl exible and effective manner was included as an indicator of intelligence (Gardner, 1993). Thus emerged the Model of Multiple Intelligences (Gardner, 1993), which proposed eight different forms of intelligence, each one associated with a form of mental rep-resentation: logical intelligence, pertaining to the sciences; linguistic intelligence, expressed in good writing; spatial intelligence, involving a three-dimensional men-tal model; kinaesthetic intelligence, the body’s ability to perform activities; natu-ralist intelligence, needed to observe nature; musical intelligence, typical among dancers; and fi nally intra-personal and inter-personal intelligence, which make up what would later be called emotional intelligence (henceforth EI), and determine the ability to satisfactorily manage behaviour through life. These intelligences are different and independent, and can be strengthened independently.

Menges, 2015; Petrides, Mikolajczak, Mavroveli, Sánchez-Ruiz, Furnham and Pé-rez González, 2016; Vallés, 2008).

The analytical perspectives used to study EI include: 1) Theoretical Models of Ability (focusing on mental abilities that allow information coming from emotions to be used to enhance the cognitive process), and 2) Mixed Models (which combine mental abilities with personality traits). According to the proponents of Ability Models (Mayer and Salovey, 1995), EI involves a set of interrelated cognitive abili-ties representing the intersection between general mental capacity (reasoning) and emotions, and differ from the personality and behaviour traits (empathy, assertive-ness, etc.) defended in Mixed Models. This perspective holds that EI is arranged in a hierarchy of aptitudes or branches.

Mayer and Salovey (1995) originally postulated that EI could comprise three mental abilities: assessment and expression, regulation (or management), and use of emotions. These authors built on this construct, resulting in the presentation and subsequent development of their four branch model. This new conceptu-alisation of EI reformulated the initially proposed abilities to include a new ap-titude –understanding emotions– and distinguishes between capacities oriented towards emotional experience, and those oriented towards their transformation. The authors consider EI as a mental capacity structured in four levels: perceiving emotions, facilitating emotions, understanding emotions and regulating emo-tions (Mayer and Salovey, 1997). The three-dimensional conceptualisation of EI has been widely embraced in the Spanish and Latin American context. In this line, Fernández-Berrocal and Ramos (2004) proposed a conception of EI in three processes: perception (conscious recognition of emotions and identifi cation of what one feels, and the ability to name emotions); understanding (integration of what one knows into one’s thoughts, and the ability to consider the complexity of emotional changes); and regulation (guiding and managing both positive and negative emotions effi ciently), which has been upheld by many authors (Car-ranza-Lira, 2017; Cejudo, García-Maroto and López-Delgado, 2017; Estrada, Monferrer and Moliner, 2016; Gónzalez-Cabrera, Pérez-Sancho and Calvete, 2016). This is due in large part to the simplicity and low cost of administrating the Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS; Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey and Palfai, 1995) measurement instrument, which these authors have simplifi ed and adapted to the Spanish context.

2017; Escoda, 2016). This consideration favours attention processes by redirecting attention to the information required in these circumstances (Mayer, 2001).

LEARNINGSTYLESBASEDONTHEWHOLEBRAINMODEL ANDEMOTIONALINTELLIGENCE

There now appears to be a certain agreement on the widespread belief that indi-viduals cannot learn in isolation from their emotions, but that they also need to know how to manage them. According to Herrmann’s (1989) postulates, this emo-tion management does not seem to fall exclusively into one single quadrant, but is present through the development of EI in the whole cognitive process entailed in learning. Effective education will therefore improve academic performance nota-bly when students are trained to use the four brain quadrants (Gómez, 2004). In-deed, Herrmann (1989) holds that one hemisphere is no more important than the other, arguing that both are needed to carry out all tasks, especially complex ones. The use of mixed learning strategies, Gardié (1998) argues, strengthens over-all development and brings individuals closer to academic excellence by over-allowing a diverse range of resources and opportunities to develop. Thus, although the brain is structured in hemispheres and quadrants, each with its own specifi c functions, all of them are needed to manage emotional information effi ciently, and thus improve effectiveness and performance. These arguments lead to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Learning styles based on mixed dominances positively infl u-ence the development of students’ emotional intelligu-ence.

As noted above, each person has their own way of learning with a preference for one or other hemisphere (Casado, Llamas and López, 2015; Desrosiers, 2005; Mayolas, Villarroya and Reverter, 2010). A person with dominance in quadrants A or B tends to be methodical, describe processes and enjoy making sense of results, and thus is positively related with a theoretical learning style. These characteristics differ in individuals with dominance in quadrants C or D, who prefer aesthet-ics, emotions, new experiences and interpersonal relationships, and act according to their feelings; they favour a more active and emotional learning style over the rationality of the latter (Maureira, Aravena, Gálvez and Cea, 2016). We therefore propose the following research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Learning styles associated with the right hemisphere make a greater contribution to the development of students’ emotional intelligence.

Figure 1. Model of the effects of learning style on students’ emotional intelligence

Having set out the research hypotheses, we now describe the research methodol-ogy and present the results. The paper ends with a discussion of the main conclu-sions and recommendations.

METHOD

Sampling and Data Collection

To test the research hypotheses and in order to cover the typologies from previous studies, we focused on second and third course students from eight academic spe-cialities taught at the Universitat Jaume I of Castellón (Spain) structured in three different branches corresponding to each faculty (Humanities and Social Sciences, Experimental Sciences, and Law and Economics).

in-vited to complete the questionnaire, with particular emphasis on the following three points: (1) the data obtained from the questionnaire would be used solely for research purposes, and the survey was therefore not connected to evaluated course content in any way; (2) respondents were guaranteed full confi dentiality and ano-nymity, as the data would be aggregated and in no case treated on an individual ba-sis; (3) participants were asked to respond sincerely in order to safeguard the value and objectivity of the data obtained. In sum, the students were clearly informed that the questionnaire was not a test or exam, and therefore there were no right and wrong answers, but rather personal preferences and expectations for each of the aspects dealt with. By following these steps we hoped to avoid the social desir-ability bias that can arise if students respond with the social purpose of projecting a distorted image, whether positive or negative (Fernández-Berrocal and Extremera, 2005).

The fi eldwork undertaken with a convenience sample during the second se-mester of the 2015-2016 academic year. We obtained 853 valid responses divided equally among the three faculties.

Of the total, 467 were women (54.7%) and 386 were men (45.3%). The stu-dents’ age range was between 19 and 22 years, with an average value of 20 years. Table 1 reports the descriptive data for the sample regarding learning styles and emotional intelligence.

Table 1. Summary of the descriptive analysis of the sample

FACULTY (N; %) DEGREES (N; %) LEARNING STYLES M (SD) EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE M (SD)

A B C D PER UND REG

Law and Economics (298; 34.9%) Business Administration (298; 34.9%) 3.3 (0.777) 3.8 (0.867) 3.2 (0.809) 3.4 (0.752) 3.6 (0.792) 3.5 (0.750) 3.5 (0.859) Humanities and Social Sciences (276; 32.4%) Audiovisual Communication (149; 17.5%) 2.4 (0.962) 3.7 (0.950) 3.5 (0.860) 3.7 (0.729) 3.6 (0.741) 3.3 (0.777) 3.3 (0.909) Advertising and Public Relations (127; 14.9%) 2.5 (0.878) 3.7 (1.020) 3.7 (0.950) 3.7 (0.717) 3.7 (0.934) 3.2 (0.840) 3.4 (0.904)

FACULTY (N; %) DEGREES (N; %) LEARNING STYLES M (SD) EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE M (SD)

A B C D PER UND REG

Humanities and Social Sciences (276; 32.4%)

Faculty Total 2.4 (0.924) 3.7 (0.981) 3.6 (0.904) 3.7 (0.725) 3.6 (0.835) 3.2 (0.806) 3.4 (0.906) Experimental Sciences (279; 32.7%)

Agrifood and Rural Engineering (57; 6.7%) 3.8 (0.675) 3.8 (0.932) 3.4 (0.831) 3.7 (0.634) 3.7 (0.746) 3.5 (0.745) 3.7 (0.855) Electrical Engineering (44; 5.2%) 3.7 (0.641) 3.6 (1.035) 3.0 (1.130) 3.4 (0.766) 3.2 (1.105) 3.4 (0.902) 3.4 (0.851) Mechanical Engineering (66; 7.7%) 3.8 (0.925) 3.2 (1.038) 2.9 (1.060) 3.4 (0.651) 3.0 (1.086) 3.1 (0.996) 3.3 (0.913) Chemical Engineering (57; 6.7%) 3.8 (0.870) 3.5 (1.217) 2.9 (1.183) 3.6 (0.891) 3.2 (1.055) 3.2 (1.014) 3.1 (1.041) Industrial Technology Engineering (55; 6.4%) 3.6 (0.782) 3.4 (1.090) 3.0 (1.101) 3.4 (0.797) 3.3 (1.137) 2.9 (0.913) 3.2 (1.090)

Faculty Total 3.7 (0.796) 3.5 (1.091) 3.0 (1.071) 3.5 (0.752) 3.2 (1.052) 3.2 (0.942) 3.3 (0.967)

Sample Total 3.1

(0.996) 3.7 (0.989) 3.3 (0.958) 3.5 (0.752) 3.5 (0.915) 3.3 (0.850) 3.4 (0.915)

Note: A = Quadrant A; B = Quadrant B; C = Quadrant C; D = Quadrant D; PER = Emotional perception; UND = Emotional understanding; REG = Emotional regulation

Table 2: Summary of the Chi-square test regarding gender factor (α=0.05)

FACTOR VALUE DF SIGNIFICATION

Quadrant A 11.007 8 0.201

Quadrant B 5.064 8 0.751

Quadrant B 4.371 8 0.822

Quadrant B 8.972 8 0.345

Emotional perception 11.019 16 0.808

Emotional understanding 10.716 16 0.827

Emotional regulation 4.071 16 0.999

Measurement Instruments

The constructs analysed in the study were measured using two fi ve-point Likert diagnosis instruments from a broad scientifi c corpus of previous research in teach-ing contexts.

First, we used a shorter adaptation of Whole Brain Theory Diagnosis, Jimé-nez’s (2006) measurement instrument based on the Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument (HBDI) (Herrmann, 1989) to measure the dominant learning styles among students. This is an eight-item self-report instrument (see Table 3) that gathers, on a fi ve-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree; 5 = completely agree), respondents’ opinions of their own degree of performance in each of the aspects or activities associated with the four brain quadrants (2 items associated with each quadrant).

both Spain and Latin America (Antonio-Aguirre, Esnaola and Rodríguez-Fernán-dez, 2017; Fernández-Berrocal and Extremera, 2005; Salove, Stroud, Woolery and Epel, 2002): the Spanish Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS-24; Fernández-Berrocal, Alcaide, Domínguez, Femández-McNally, Ramos and Ravira,1998, 2004; based on Salovey Mayer, Goldman, Turvey and Palfai's original scale, 1995). As shown in Table 4, this is a meta-knowledge trait scale with 12 items assessed on a fi ve-point Likert scale to assess level of agreement with the items (1 = completely disagree; 5 = completely agree), which yields the perceived emotional intelligence rate through three factors: perception, understanding and regulation of one’s own emotions (four items per factor).

Although neither of these diagnostic instruments was initially conceived as part of causal research methodology, such as the structural equations models (SEM) technique used in this study, several factors justify its application in this new methodological context.

First, in self-report data collection processes this kind of instrument guaran-tees ease of understanding and administration for students, in terms of both time and form. Secondly, both instruments refl ect conceptualisations associated with basic learning and emotional skills. Third, because they are designed to encourage introspection, they allow researchers to assess underlying processes that are not easily measured with alternatives such as skill tasks.

As mentioned earlier in the article, we used the shorter versions of both scales since we were looking for a general medium-length questionnaire that would not interfere with levels of concentration and sincerity in the students’ responses. Ad-ditionally, SEM does not require a large number of indicators for each latent vari-able to function optimally. This also helps to prevent a major problem in fi eldwork among students, namely, potential bias due to survey fatigue during completion (Fernández-Berrocal and Extremera, 2005).

Validity and Scale Reliability

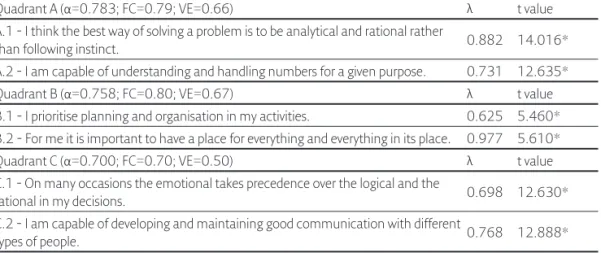

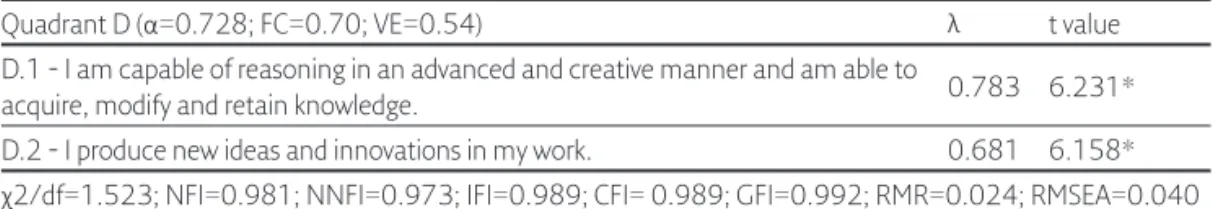

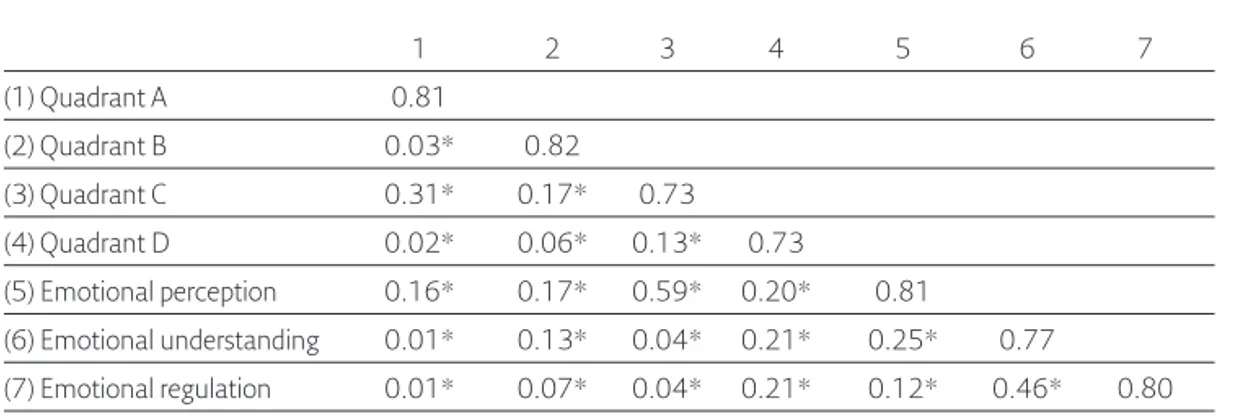

The scales were refi ned by confi rmatory factor analysis for SEM using the sta-tistical program EQS 6.1. This methodology allows researchers to test theoreti-cal models that contain both the latent variables representing a given theoretitheoreti-cal concept, and the indicators designed to measure them, making this method an es-sential tool to validate measurement scales (Steenkamp and Van Trijp, 1991). The parameters were estimated using the robust maximum likelihood approach.

we fi rst examined the estimation parameters. The indicators satisfi ed the strong convergence condition with individual standardised coeffi cients ( ) above 0.6 and a mean factor loading value higher than 0.7 (Bagozzi and Youjae, 1988; Steenkamp and Van Trijp, 1991; Hair et al., 2009). We then confi rmed that the weak conver-gence condition was satisfi ed by analysing the signifi cance of the factor regression coeffi cients compared to their corresponding latent variable (Steenkamp and Van Trijp, 1991). To this end we reviewed the minimum requirement of Student’s t statistic (t > 2.58; P = 0.01). Finally, the main goodness-of-fi t indices were ob-tained. The fi t of the conceptual model to the empirical data was studied with the following statistics: normed 2, normed fi t index (NFI), non-normed fi t index (NNFI), incremental fi t index (IFI), comparative fi t index (CFI), goodness-of-fi t index (GFI), root mean square residual (RMR) and root mean square of approxi-mation (RMSEA).

Various tests were then performed to ensure that the refi nement process had not affected the scales’ reliability: the reliability coeffi cient analysis to assess the in-ternal consistency using Cronbach’s (Nunnally, 1979), and the composite reliabil-ity of the construct (FC). In both cases, values higher than 0.7 were considered ac-ceptable (Fornell and Lacker, 1981; Hair et al., 2009). The variance extracted (VE) was also analysed, the minimum acceptable value being 0.5 (Fornell and Lacker, 1981; Hair et al., 2009). The results of these tests are reported in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3. Summary of the factor analyses and the validity and reliability analyses of the measurement scales for the students’ learning styles

Quadrant A (α=0.783; FC=0.79; VE=0.66) λ t value

A.1 - I think the best way of solving a problem is to be analytical and rational rather

than following instinct. 0.882 14.016*

A.2 - I am capable of understanding and handling numbers for a given purpose. 0.731 12.635*

Quadrant B (α=0.758; FC=0.80; VE=0.67) λ t value

B.1 - I prioritise planning and organisation in my activities. 0.625 5.460* B.2 - For me it is important to have a place for everything and everything in its place. 0.977 5.610*

Quadrant C (α=0.700; FC=0.70; VE=0.50) λ t value

C.1 - On many occasions the emotional takes precedence over the logical and the

rational in my decisions. 0.698 12.630*

C.2 - I am capable of developing and maintaining good communication with different

types of people. 0.768 12.888*

Quadrant D (α=0.728; FC=0.70; VE=0.54) λ t value D.1 - I am capable of reasoning in an advanced and creative manner and am able to

acquire, modify and retain knowledge. 0.783 6.231*

D.2 - I produce new ideas and innovations in my work. 0.681 6.158*

χ2/df=1.523; NFI=0.981; NNFI=0.973; IFI=0.989; CFI= 0.989; GFI=0.992; RMR=0.024; RMSEA=0.040 Note: *p<0.01

Table 4. Summary of the factor analyses and the validity and reliability analyses of the measurement scales for the students’ emotional intelligence

Perception (α=0.881; FC=0.88; VE=0.65) λ t value

PERCE.1 - I usually care a lot about what I feel. 0.837 7.014*

PERCE.2 - I usually spend time thinking about my emotions. 0.865 6.759*

PERCE.3 - I often think about my feelings. 0.614 7.597*

PERCE.4 - I pay a lot of attention to how I feel. 0.878 11.581*

Understanding (α=0.853; FC=0.85; VE=0.59) λ t value

UNDERSTAND.1 - I am very clear about my feelings. 0.766 23.307*

UNDERSTAND.2 - I can normally defi ne my feelings. 0.815 25.586*

UNDERSTAND.3 - I almost always know how I am feeling. 0.802 25.597*

UNDERSTAND.4 - I can always tell how I feel. 0.674 20.753*

Regulation (α=0.863; FC=0.87; VE=0.64) λ t value

REGUL.1 - Even if I’m feeling sad, I usually have an optimistic outlook. 0.763 24.753* REGUL.2 - Even if I’m feeling bad, I try to think about pleasant things. 0.924 32.870*

REGUL.3 - When I get upset, I remind myself of all the pleasures in life. 0.681 21.792* REGUL.4 - I try to think positive thoughts even if I’m feeling upset. 0.803 26.612*

χ2/df=1.986; NFI=0.978; NNFI=0.963; IFI=0.983; CFI= 0.983; GFI=0.977; RMR=0.038; RMSEA=0.060 Note: *p<0.01

Table 5. Discriminant validity of the measurement scales

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

(1) Quadrant A 0.81

(2) Quadrant B 0.03* 0.82

(3) Quadrant C 0.31* 0.17* 0.73

(4) Quadrant D 0.02* 0.06* 0.13* 0.73

(5) Emotional perception 0.16* 0.17* 0.59* 0.20* 0.81

(6) Emotional understanding 0.01* 0.13* 0.04* 0.21* 0.25* 0.77

(7) Emotional regulation 0.01* 0.07* 0.04* 0.21* 0.12* 0.46* 0.80

Note: the estimated correlation between the factors is shown below the diagonal; the square root of the VE is on the diagonal; * p<.01

The analyses undertaken with this methodology guarantee consistency of the model with its theoretical proposals for each of the scales used, based on reliable and valid scales for empirical use in the fi eldwork.

Additionally non-response bias was analysed using a means analysis for inde-pendent samples with SPSS 18.0 for each of the items in the refi ned scales. The fi rst 50 responses were compared with the last 50. In all cases equal variance was assumed, therefore confi rming the absence of non-response bias (Armstrong and Overton, 1977).

Finally, possible common method variance bias was controlled for with Har-man’s (1976) test, which concluded that the bias resulting from the method used was not a problem for the validity of the results on testing subsequent hypotheses (Pod-sakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Pod(Pod-sakoff, 2003; Friedrich, Byre and Mumford, 2009).

RESULTS

Table 6. Summary of the results of the structural models

RELATION PARAMETER T

A.1 Quadrant A A Emotional perception -0.154 -2.776**

A.2 Quadrant A A Emotional understanding -0.015 -0.416

A.3 Quadrant A A Emotional regulation 0.003 0.093

χ2/df=3.295; NFI=0.964; NNFI=0.954; IFI=0.973; CFI= 0.973; GFI=0.965; RMR=0.043; RMSEA=0.059

B.1 Quadrant B A Emotional perception 0.188 4.301**

B.2 Quadrant B A Emotional understanding 0.154 3.549**

B.3 Quadrant B A Emotional regulation 0.096 2.308*

χ2/df=2.288; NFI=0.976; NNFI=0.936; IFI=0.980; CFI= 0.980; GFI=0.976; RMR=0.035; RMSEA=0.070

C.1 Quadrant C A Emotional perception 0.596 10.511**

C.2 Quadrant C A Emotional understanding 0.109 2.518*

C.3 Quadrant C A Emotional regulation 0.018 0.440

χ2/df=4.228; NFI=0.967; NNFI=0.927; IFI=0.972; CFI= 0.972; GFI=0.968; RMR=0.038; RMSEA=0.060

D.1 Quadrant D A Emotional perception 0.236 5.262**

D.2 Quadrant D A Emotional understanding 0.274 5.949**

D.3 Quadrant D A Emotional regulation 0.264 5.902**

χ2/df=2.901; NFI=0.962; NNFI=0.961; IFI=0.973; CFI= 0.972; GFI=0.964; RMR=0.043; RMSEA=0.054

Note: *p<0.05; **p<0.01

Figure 2 shows that all the proposed learning style relations associated with quad-rants B and D are positive and signifi cant (relations B.1, B.2, B.3 and D.1, D.2, D.3). Learning style relations associated with quadrant C (relations C.1, C.2) are also positive and signifi cant, except relation C.3. The two research hypotheses are therefore confi rmed.

Figure 2. Summary of the model of effects

Note: represents a signifi cant negative effect; represents a signifi cant positive effect; represents a non-signifi cant effect

DISCUSSION

Over the last decades, the literature has refl ected a steady interest in determining students’ learning styles, which in turn have proved useful for designing train-ing curricula (Cárdenas, Conde-González and Perales, 2015) aimtrain-ing to respond to student interests and motivations through contextualised and meaningful learning. Achieving this goal appears to be conditioned by the creative construction of fa-vourable environments that take into account personal styles and preferences, and where students are the protagonists in their own training process.

technical and professional skills, but also with well-developed social and emotional skills. In this context, the present study proposes an innovative theoretical model that relates learning styles according to the postulates of the whole brain theory with the development of these social and emotional skills proposed by EI. The principal objective of the study is to offer a set of didactic proposals on how best to approach the teaching of university students, taking into account their learn-ing styles, thus leadlearn-ing to a general refl ection on the most appropriate teachlearn-ing methods to provide the most comprehensive education possible and unlock the full potential of students’ abilities.

Additionally, the rapid development of neuroscience suggests we should con-sider that learning styles are conditioned by brain dominance and by the degree curricula. Thus, Segarra, Estrada and Monferrer (2015) and Estrada, Monferrer and Moliner (2016) highlight the need to review the curricula design in university degrees to promote learning styles with certain brain dominance over others. One example is the engineering degree programmes associated with developing com-petencies related to quadrants A and B, which contribute little to the competences developed in quadrants D and C; this situation is reversed in programmes designed for humanities and social science degrees. We can infer, therefore, that the brain dominance used in the learning style assumes that degrees apply the aptitudes de-termining good development of EI in different ways. On this point the confi rma-tion of our fi rst hypothesis endorses the idea that students need to be trained to use a learning style that allows for mixed dominances, which in turn, will help develop their EI. Gómez (2004) and Ferrer, Villalobos, Morón, Montoya and Vera (2014) hypothesised that when students are trained to use the four brain quadrants, education becomes more effective and students’ academic performance notably improves. Indeed, Herrmann (1989) and Herrmann and Herrmann-Nehdi (2015) point out that any task, especially complicated tasks, requires both hemispheres, thus implying that all four emotional competencies should be developed (Mayer and Salovey, 1997). Salas’s (2008) study found that students’ development of the four brain quadrants requires a favourable environment for the process. Modify-ing this environment frequently depends on the teachers’ teachModify-ing-learnModify-ing style (Estupiñán, Cherrez, Intriago and Torres, 2016).

competencies of perception and understanding, but not regulation. This is because the individuals’ holistic profi le poses certain problems for controlling and regulating the tangle of emotions and feelings facing their learning style. We therefore recom-mend teachers focus on training activities to develop the control competence. In contrast, learning styles associated with the left hemisphere revealed less develop-ment of emotional competencies. Although dominance in quadrant B yields positive results in emotional intelligence, quadrant A provides no signifi cant results in under-standing and regulation competencies, and is negative in the relation with emotional perception. The reason for these results is that it is essentially a rational learning style that grants little relevance to emotions and their management.

Schmidt (2002), an author critical of EI in the world of work, suggests EI may be considered as one of the constructs related to individual differences that may be useful for constructing successful performance models. This author argues that EI is particularly useful for successful performance in professions involving interaction with other people and that often place employees in highly emotionally charged situations. It is therefore crucial to train tomorrow’s professionals using learning styles that enable their EI to develop and that can prepare them to make better use of cognitive capabilities for processing emotional information, thus becoming effi cient professionals and healthy citizens (Lopes, Brackett, Nezlek, Schütz, Sell-in and Salovey, 2006; Molero, Pantoja-Vallejo and Galiano-Carrión, 2017; Sáez, Lavega, Mateu and Rovira, 2014). In this vein, and coinciding with Rojas et al. (2006), one of the lessons that educators can learn from the fi ndings of this study is that instruction becomes more effective, the more the content is presented not only in the traditional verbal modality (stimulating the left hemisphere, quadrants A and B), but also in the non-verbal or representational modality (graphics, images, pictures, etc.), which help to stimulate the right hemisphere (quadrants C and D). This fi nding leads us to propose a mixed teaching strategy that combines sequen-tial and linear techniques with other approaches that allow students to see patterns by making use of visual and spatial thought, and deal with the whole as well as the parts. The following teaching strategies can be used to this effect: role-plays, direct experience, practical cases, multi-sensory learning, music, art, comics, cin-ema, etc. In addition, the results should prompt refl ection on the current curricula of many degrees, which are frequently designed to encourage certain dominance styles to the detriment of others. Finally, we propose the development of training programmes for educators to enable them to develop mixed methodologies that stimulate their students’ holistic development.

universities and secondary schools in order to compare results. Second, although the TMMS-24 measurement instrument has been widely used in the Spanish and Latin American context, its current use is perhaps excluding other alternative op-tions.

Finally, it should be noted that during this academic year, educators from the subjects and degrees involved in the study have redesigned the methodologies they use by incorporating mixed learning strategies aimed to develop learning styles in universities with dominances in most of the brain’s quadrants, thus maximising stu-dents’ technical and emotional capabilities to the full. We are currently analysing the data obtained and hope that the outcomes will allow us to continue exploring this research line further. We are also working to open up new channels for col-laboration with other universities and secondary schools in order to replicate the model.

Fecha de recepción del original: 13 de abril 2018

Fecha de aceptación de la versión defi nitiva: 6 de noviembre 2018

REFERENCES

Akhtar, R., Boustani, L., Tsivrikos, D. and Chamarro-Premuzic, T. (2015). The engageable personality: personality and trait EI as predictors of work engage-ment. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 44-49.

Alonso, C., Domingo, J. and Honey, P. (1994). Los estilos de aprendizaje: procedimien-tos de diagnóstico y mejora. Bilbao: Ediciones Mensajero.

Andrei, F., Siegling, A. B., Aloe, A. M., Baldaro, B. and Petrides, K. V. (2016). The incremental validity of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality Assess-ment, 98, 261-276.

Antonio-Agirre, I., Esnaola, I. and Rodríguez-Fernández, A. (2017). La medida de la inteligencia emocional en el ámbito psicoeducativo. Revista Interuniversi-taria de Formación de Profesorado, 88(31.1), 53-64.

Armstrong, J. S. and Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating non-response bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research,16,396-402.

Bagozzi, R. P. and Youjae, Y. (1988). On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,16, 74-94.

Blaney, P. H. (1986). Affect and memory: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 229-246.

Brookfi eld, S. D. (1995). Becoming a critically refl ective teacher. San Francisco: Jos-sey-Bass.

Camarero, F., Martín, F. y Herrero, J. (2000). Estilos y estrategias de aprendizaje en estudiantes universitarios. Psicothema, 12(4), 615-622.

Cárdenas, D., Conde-González, J. and Perales, J. C. (2015). El papel de la carga mental en la planifi cación del entrenamiento deportivo. Revista Psicología del Deporte, 24(1), 91-100.

Carranza-Lira, S. (2017). Correlation between psychological state and emotional intelligence in residents of gyunbecology and obstetrics. Revista Médica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, 54(6), 780-786.

Casado, Y., Llamas, S. and López, V. (2015). Inteligencias múltiples, creatividad y lateralidad, nuevos retos en metodologías docentes enfocadas a la innovación educativa. Reidocrea, 4(43), 343-358.

Cazau, P. (2004). Estilos de aprendizaje: El modelo de los cuadrantes cerebrales. In J. Gómez (Ed.), Neurociencia cognitiva y educación. Lambayeque: Fachse. Cejudo, I., García-Maroto, S. and López-Delgado, M. L. (2017). Efectos de un

programa de inteligencia emocional en la ansiedad y el autoconcepto en mu-jeres con cáncer de mama. Terapia Psicológica, 35(3), 239-246.

Damasio, A. R. (2006). El error de Descartes. Madrid: Crítica.

Desrosiers, P. (2005). Psicomotricidad en el aula. Barcelona: INDE Publicaciones. Dunn, R. and Dunn, K. (1978). Teaching students through their individual learning

styles: A practical approach. Reston: Prentice Hall.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D. and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405-432.

Escoda, N. P. (2016). Cuestionario del GROP para la evaluación de la competen-cia emocional (CDE). In J. L. Soler, L. Aparicio, O. Díaz, E. Escolano and A. Rodríguez (Coords.), Inteligencia emocional y bienestar II: Refl exiones, expe-riencias profesionales e investigación (pp. 690-705). Zaragoza: Universidad San Jorge.

Estrada, M., Monferrer, D. and Moliner, M. A. (2016). Entrenamiento de la inteli-gencia emocional en el contexto de la formación en ventas. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 27(2), 62-79.

la formación profesional. Neurociencia Cognitiva e Inteligencia Emocional. Didasc@lia: Didáctica y Educación, VII(4), 207-214.

Extremera, N., Fernández-Berrocal, P., Mestre, J. M. and Guil, R. (2004). Me-didas de evaluación de la inteligencia emocional. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 36(2), 209-228.

Fernández-Berrocal, P. and Extremera, N. (2005). La inteligencia emocional y la educación de las emociones desde el Modelo de Mayer y Salovey. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 19(3), 63-93.

Fernández-Berrocal, P. and Ramos, N. (2004). Desarrolla tu inteligencia emocional. Barcelona: Kairós.

Fernández-Berrocal, P., Alcaide, R., Domínguez, E., Femández-McNally, C., Ra-mos, N. S. and Ravira, M. (1998). Adaptación al castellano de la escala rasgo de metaconocimiento sobre estados emocionales de Salovey, et al. Libro de Actas del V Congreso de Evaluación Psicológica (pp. 83-84). Málaga: Universidad de Málaga.

Fernández-Berrocal, P., Extremera, N. and Ramos, N. (2004). Validity and reliabil-ity of the Spanish modifi ed version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychologi-cal Reports, 94, 751-755.

Ferrer, K., Villalobos, J., Morón, A., Montoya, C. and Vera, L. (2015). Estilos de pensamiento según la teoría de cerebro integral en docentes del área de quí-mica de la Escuela de Bioanálisis. Multiciencias, 14(3), 281-288.

Flores, E. and Maureira, F. (2015). Propiedades psicométricas del inventario de dominancia cerebral en estudiantes de educación física. Emásf: Revista Digital de Educación Física, 36, 81-91.

Forgas, J. P. (2000). Feeling and thinking: the role of affect in social cognition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fornell, C. and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39-50.

Friedrich, T. L., Byre, C. L. and Mumford, M. D. (2009). Methodological and the-oretical considerations in survey research. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 57-60. Gardié, O. (1998). Total brain and a creative wholistic view of education. Estudios

Pedagógicos, 24, 79-87.

Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice. New York: Basic Books.

Gómez, J. (2004). Neurociencia cognitiva y educación. Lambayeque: Fachse.

González-Arias, M. I. and Alucema, L. B. (2015).Formación universitaria en ca-rreras de ingeniería y pedagogía. Revisitando un antiguo debate. Formación Universitaria, 8(6), 13-22.

Gónzalez-Cabrera, J., Pérez-Sancho, C. and Calvete, E. (2016). Diseño y vali-dación de la escala de inteligencia emocional en internet para adolescentes. Psicología Conductual, 24(1), 93-105.

Guilford, J. P. (1985). The structure of intellect model. In B. B. Wolman (Ed.), Handbook of Intelligence. Theories, measurements, and applications (pp. 225-266). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J. and Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate Data Analysis. Nueva York: Prentice Hall.

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Herrmann, N. (1989). The creative brain. Lake Lure: Brain Books.

Herrmann, N. and Herrmann-Nehdi, A. (2015). The Whole Brain business book: Un-locking the power of whole brain thinking in organizations, teams, and individuals. London:McGraw Hill Professional.

Hilgard, E. R. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of Behavior Sciences, 16, 107-117.

Jiménez, C. A. (2006). Diagnóstico teoría del cerebro total. Perieda: Magisterio. LeDoux, J. (2002). Synaptic self: How our brains become who we are. New York:

Pen-guin Books.

Lopes, P. N., Grewal, D., Kadis, J., Gall, M. and Salovey, P. (2006). Evidence that emotional intelligence is related to job performance and affect and attitudes at work. Psicothema, 18, 132-138.

Lopes, P. M., Brackett, M. A., Nezlek, J. B., Schütz, A., Sellin, I. and Salovey, P. (2004). Emotional intelligence and socialinteraction. Personality and Social PsychologyBulletin, 30(8), 1018-1034.

López-Zafra, E., Pulido-Martos, M., Berrios, M. and Augusto-Landa, J. M. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the work group emotion intelligence prolife-short version. Psicothema, 24(3), 495-502.

MacLean, P. D. (1990). The triune brain in evolution: Role in paleocerebral functions. New York: Planum Press.

Mallart, J. (2000). Didáctica: Del currículum a las estrategias de aprendizaje. Re-vistaEspañola de Pedagogía, 58(217), 417-438.

de pedagogía en educación física de la USEK de Chile. Revista de psicología Iztacala, 17(4), 1559-1579.

Maureira, F., Flores, E., Gálvez, C., Cea, S., Espinoza, E., Soto, C. and Martínez, J. (2016). Relación entre coefi ciente intelectual, inteligencia emocional, do-minancia cerebral y estilos de aprendizaje Honey-Alonso en estudiantes de educación física en Chile. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala, 19(4), 1206-1220.

Mayer, J. D. and Salovey, P. (1995). Emotional intelligence and the identifi cation of emotion. Intelligence, 22, 89-113.

Mayer, J. D. and Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey and D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Implica-tions for educators (pp. 3-31). New York: Basic Books.

Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. and Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets tra-ditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence, 27, 267-298.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P. and Caruso, D. (2001). Technical Manualfor the MSCEITv. 2.0. Toronto: MHS Publishers.

Mayolas, M. C., Villarroya, A. and Reverter, J. (2010). Relación entre la lateralidad y los aprendizajes escolares. Revista Apuntes de Educación Física y Deportes, 101, 32-42.

Molero, D., Pantoja-Vallejo, A. and Galiano-Carrión, M. (2017). Inteligencia emocional rasgo en la formación inicial del profesorado. Contextos Educativos, 20, 43-56.

Momm, T., Blickle, G., Liu, Y., Wihler, A., Kholin, M. and Menges, J. I. (2015). It pays to have an eye for emotions: Emotion recognition ability indirectly predicts annual income. Journal ofOrganizationalBehavior, 36(1), 147-163. Nunnally, J. (1979). Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Perea, R. (2011). Impacto de las infotecnologías, la neurociencia y la neuroética en la Educación. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 69(249), 289-304.

Pérez-Fuentes, M., Molero, M., Gázquez, J. and Soler, F. (2014). Estimulación de la inteligencai emocional en mayores: El programa PECI-PM. European Journal of Investigation in Health. Psychology and Education, 4(3), 329-339. Petrides, K.V. and Furnham, A. (2003). Trait emotional intelligence: Behavioral

validation in two studies of emotion recognition and reactivity to mood in-duction. European Journal of Personality, 17, 39-57.

Petrides, K. V., Mikolajczak, M., Mavroveli, S., Sánchez-Ruiz, M., Furnham, A. and Pérez González, J. C. (2016). Developments in trait emotional intelli-gence research. EmotionReview, 8(4),335-341.

method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879-903.

Rojas, G., Salas, R. and Jiménez, C. (2006). Estilos de aprendizaje y estilos de pensamiento entre estudiantes universitarios. Estudios Pedagógicos, XXXII(1), 49-75.

Rosa, G., Riberas, G., Navarro, L. and Vilar, J. (2015). El coaching como herrami-enta de trabajo de la competencia emocional en la formación de estudiantes de educación social y trabajo social de la Universidad Ramón Llull, España. Formación Universitaria, 8(5), 77-89.

Sáez, U., Lavega, P., Mateu, M. and Rovira, G. (2014). Emociones positivas y edu-cación de la convivencia escolar. Contribución de la expresión motriz coope-rativa. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 32(2), 309-326.

Said, P. B., Díaz, M. V., Chiapello, J. A. and Espindola, M. E. (2010). Estilos de aprendizaje en estudiantes que cursan la primera asignatura de la carrera de medicina en el nordeste Argentino. Revista de Estilos de Aprendizaje, 6, 67-79. Salas, R. (2008). Estilos de aprendizaje a la luz de la neurociencia. Bogotá: Magisterio. Salas, R. S., Santos, M. A. and Parra, S. (2004). Enfoques de aprendizaje y

domi-nancias cerebrales entre estudiantes universitarios. Revista Aula Abierta, 84, 3-22.

Salomon, R. C. (1993). The Philosophy of emotions. In M. Lewis y J. M. Haviland (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 3-15). New York: Guilford Press.

Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Goldman, S. L., Turvey, C. and Palfai, T. P. (1995). Emo-tional attention, clarity, and repair: exploring emoEmo-tional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In J. W. Pennebaker (Ed.), Emotion, Disclosure, & Health (pp. 125-154). Washington: American Psychological Association. Salovey, P., Stroud, L. R., Woolery, A. and Epel, E. S. (2002). Perceived emotional

intelligence, stress reactivity, and symptom reports: Further explorations us-ing the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychology and Health, 17, 611-627.

Sánchez, A. G. (2010). Diagnóstico de estilos de aprendizaje en estudiante univer-sitarios de nuevo ingreso basado en la dominancia cerebral. Estilos de aprendi-zaje, 5(5), 43-52.

Schmidt, F. L. (2002). The role of general cognitive ability and job performance: Why there cannot be a debate. Human Performance, 15, 187-210.

Segarra, M., Estrada, M. and Monferrer, D. (2015). Estilos de aprendizaje en los estudiantes universitarios: Laterización vs. interconexión de los hemisferios cerebrales. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 73(262), 583-600.

Sperry, R. W. (1961). Cerebral organization and behaviour. Science, 133, 1749-1757.

Steenkamp, J. B. E. M. and Van Trijp, H. C. M. (1991). The use of Lisrel in validat-ing marketvalidat-ing constructs. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 8(4), 283-299.

Sterberg, R. J. (1985). Beyond IQ: A triarchic Theory of intelligence. Cambridge: Cam-bridge University Press.

Vallés, A. (2008). La inteligencia emocional de los padres y de los hijos. Madrid: Pirámide. Velásquez, B. and Remolina, N. (2013). Análisis correlacional del perfi l de domi-nancia cerebral de estudiantes de la salud y estudiantes de ciencias sociales de la Universidad Colegio Mayor de Cundinamarca. NOVA, 11(20), 71-82. Velásquez, B., Remolina, N. and Calle, M. G. (2007). Determinación del perfi l de

dominancia cerebral o formas de pensamiento de los estudiantes del primer se-mestre del programa de bacteriología y laboratorio clínico. Nova, 5(7),48-56. Warwick, J. and Nettelbeck, T. (2004). Emotional intelligence is…? Personality and