Facultat de Farmàcia

Departament de Microbiologia i Parasitologia Sanitàries

Estudi dels polihidroxialcanoats acumulats per Pseudomonas

aeruginosa

42A2: producció i caracterització

FACULTAT DE FARMÀCIA

Departament de Microbiologia i Parasitologia Sanitàries

Programa de doctorat: Química Orgànica (Facultat de Químiques)

BIENNI 2002-2004

Estudi dels polihidroxialcanoats acumulats per

Pseudomonas

aeruginosa

42A2: producció i caracterització

Memòria presentada per Mònica Bassas i Galià per optar al títol de doctor per la

Universitat de Barcelona

Director/a:

Dra. Àngels Manresa i Presas Dr. Joan LLorens i Llacuna

Doctorand:

Mònica Bassas i Galià

Taules i Figures de l’apartat de Resultats i Discussió. Fonts de carboni complexes (4.1)

RT:30.99 - 32.45

31.0 31.2 31.4 31.6 31.8 32.0 32.2 32.4

Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bu ndan ce 31.51 31.92 32.03 31.84 31.71 31.08 32.14

31.25 31.40 32.25

NL: 2.50E7 TIC M S Monica 14

(a)

PM= 472 g/mol m/z 271 (361-TMSOH)

Monica 14 #1188-1193 RT:31.77-31.88 AV:6 NL:3.88E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 259.1 213.1 271.1 155.0 147.0 103.0 212.1 361.1

332.1 362.1 441.2457.2 535.3 621.3647.4 662.5

(b) OTMS O O

OTMS

213

259 361

M-15

Monica 14 #1194-1198 RT:31.90-31.99 AV:5NL:9.75E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 173.1 259.1 215.1 114.0 275.1 95.0 299.1 185.1 332.1 647.4 441.2 662.5

338.1374.1 457.2 535.2 591.4

(c) O

O OTMS

OTMS OTMS

173 275 259

PM=560 g/mol m/e 185 (275-TMSOH)

m/ 83 (173-TMSOH) DHOD

THOD RT:30.99 - 32.45

31.0 31.2 31.4 31.6 31.8 32.0 32.2 32.4

Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bu ndan ce 31.51 31.92 32.03 31.84 31.71 31.08 32.14

31.25 31.40 32.25

NL: 2.50E7 TIC M S Monica 14

(a)

PM= 472 g/mol m/z 271 (361-TMSOH)

Monica 14 #1188-1193 RT:31.77-31.88 AV:6 NL:3.88E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 259.1 213.1 271.1 155.0 147.0 103.0 212.1 361.1

332.1 362.1 441.2457.2 535.3 621.3647.4 662.5

(b) OTMS O O

OTMS

213

259 361

M-15

Monica 14 #1194-1198 RT:31.90-31.99 AV:5NL:9.75E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 173.1 259.1 215.1 114.0 275.1 95.0 299.1 185.1 332.1 647.4 441.2 662.5

338.1374.1 457.2 535.2 591.4

(c) O

O OTMS

OTMS OTMS

173 275 259

PM=560 g/mol m/e 185 (275-TMSOH)

m/ 83 (173-TMSOH) RT:30.99 - 32.45

31.0 31.2 31.4 31.6 31.8 32.0 32.2 32.4

Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bu ndan ce 31.51 31.92 32.03 31.84 31.71 31.08 32.14

31.25 31.40 32.25

NL: 2.50E7 TIC M S Monica 14

(a)

RT:30.99 - 32.45

31.0 31.2 31.4 31.6 31.8 32.0 32.2 32.4

Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bu ndan ce 31.51 31.92 32.03 31.84 31.71 31.08 32.14

31.25 31.40 32.25

NL: 2.50E7 TIC M S Monica 14

(a)

PM= 472 g/mol m/z 271 (361-TMSOH)

Monica 14 #1188-1193 RT:31.77-31.88 AV:6 NL:3.88E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 259.1 213.1 271.1 155.0 147.0 103.0 212.1 361.1

332.1 362.1 441.2457.2 535.3 621.3647.4 662.5

(b) OTMS O O

OTMS

213

259 361

M-15

PM= 472 g/mol m/z 271 (361-TMSOH)

Monica 14 #1188-1193 RT:31.77-31.88 AV:6 NL:3.88E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 259.1 213.1 271.1 155.0 147.0 103.0 212.1 361.1

332.1 362.1 441.2457.2 535.3 621.3647.4 662.5 (b)

Monica 14 #1188-1193 RT:31.77-31.88 AV:6 NL:3.88E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 259.1 213.1 271.1 155.0 147.0 103.0 212.1 361.1

332.1 362.1 441.2457.2 535.3 621.3647.4 662.5

(b) OTMS O O

OTMS

213

259 361

M-15

Monica 14 #1194-1198 RT:31.90-31.99 AV:5NL:9.75E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 173.1 259.1 215.1 114.0 275.1 95.0 299.1 185.1 332.1 647.4 441.2 662.5

338.1374.1 457.2 535.2 591.4

(c) O

O OTMS

OTMS OTMS

173 275 259

PM=560 g/mol m/e 185 (275-TMSOH)

m/ 83 (173-TMSOH) Monica 14 #1194-1198 RT:31.90-31.99 AV:5NL:9.75E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 173.1 259.1 215.1 114.0 275.1 95.0 299.1 185.1 332.1 647.4 441.2 662.5

338.1374.1 457.2 535.2 591.4

(c) O

O OTMS

OTMS OTMS

173 275 259 Monica 14 #1194-1198 RT:31.90-31.99 AV:5NL:9.75E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 173.1 259.1 215.1 114.0 275.1 95.0 299.1 185.1 332.1 647.4 441.2 662.5

338.1374.1 457.2 535.2 591.4 (c)

Monica 14 #1194-1198 RT:31.90-31.99 AV:5NL:9.75E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 173.1 259.1 215.1 114.0 275.1 95.0 299.1 185.1 332.1 647.4 441.2 662.5

338.1374.1 457.2 535.2 591.4 (c)

Monica 14 #1194-1198 RT:31.90-31.99 AV:5NL:9.75E5

T:+ c Full ms [ 60.00-700.00]

100 200 300 400 500 600 700

m/z 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e Abundanc e 73.0 173.1 259.1 215.1 114.0 275.1 95.0 299.1 185.1 332.1 647.4 441.2 662.5

338.1374.1 457.2 535.2 591.4

(c) O

O OTMS

OTMS OTMS

173 275 259

PM=560 g/mol m/e 185 (275-TMSOH)

m/ 83 (173-TMSOH) DHOD

THOD

Figura 7.0. Productes de biotransformació de l’àcid linoleic.

Figura 7.2 FTIR. Espectre del PHA-linoleic obtingut a partir d’un cultiu de P. aeruginosa 42A2 emprant àcid linoleic com a font de carboni.

PHA-linoleic

500 1000 1500

2000 2500

3000 3500

nº d'ona (cm-1)

%

tr

ans

mi

tànc

ia

PHA-monodi

500 1000 1500

2000 2500

3000 3500

nº d'ona (cm-1)

%

tr

an

sm

ità

nci

a

Figura 7.1 FTIR. Espectre del PHA-monodi obtingut a partir

O O O O O O O O

C14:3 C14:2 C14:1 C14:0

O O O O * O O *

C12:2 C12:1 C12:0

O O O O C10:0 C10:1 * O O * O O C8:0 C8:1 O O O O O O O O

C14:3 C14:2 C14:1 C14:0

O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O

C14:3 C14:2 C14:1 C14:0

O O O O * O O *

C12:2 C12:1 C12:0

O O O O * O O * O O O O * O O *

C12:2 C12:1 C12:0

C12:2 C12:1 C12:0

[image:6.595.160.475.76.553.2]O O O O C10:0 C10:1 * O O * O O C8:0 C8:1 O O O O C10:0 C10:1 O O O O O O O O C10:0 C10:1 C10:0 C10:1 * O O * O O C8:0 C8:1 * O O * O O * O O * O O C8:0 C8:1 C8:0 C8:1

Figura 7.3. Monòmers del PHA-L (oli de llinosa)

Taula 7.1 Taula de desplaçaments químics de 13C per al PHA-L, obtingut a partir de l’oli de llinosa.

δδδδ (13C, ppm) C8:1∆5 C10:1∆7 C12:1∆6666 C12:2∆6,9 C14:1∆5555 C14:2∆5,85,85,85,8 C14:3∆5,8,115,8,115,8,115,8,11

C5 122.39 122.96 123.31 123.53

C6 135.41 127.9 128.23 133.84 132.03 131.63

C7 128.45 131.09 129.18

C8 132.29 127.02 127.36

C9 130.79 128.87

C10 126.9

C11 132.29 127.36

C12 132.29

Taules i Figures de l’apartat de Resultats i Discussió. Fonts de carboni definides (4.2)

m onònom e r C7:0 C9:0

C1 169.28 169.28

C2 70.82 70.82

C3 39.12 39.12

C4 33.51 33.83

C5 27.18 25.04

C6 22.46 29.06

C7 13.96 31.71

C8 22.59

C9 14.10

PHA-C9

Taula 7.313C-RMN. Taula de desplaçaments

químics per al PHA-C9:0

m onòm e r C7:0 C9:0 C11:0

C1 169.31 169.31 169.31

C2 70.83 70.83 70.83

C3 39.11 39.11 39.11

C4 33.5 33.83 33.83

C5 27.18 25.03 25.03

C6 22.44 29.05 22,3-22,8

C7 13.95 31.70 22,3-22,8

C8 22.58 22,3-22,8

C9 14.07 31.86

C10 22.67

C11 14.12

PHA-C11:0

13

HPR F5 HPR F7 HPR F9 HPR F10

Biomassa (g/L) 1,52 2,46 3,6 3,3

PHA (g/L) 0,59 0,88 1,82 1,5

PHA (%w /w ) 39 36 50 45,3

temps (h) 103 121 120 93

Yx/s 0,15 0,21 0,19 0,23

Yp/s 0,06 0,08 0,10 0,10

Yx/N 2,62 4,24 6,21 5,69

g/L NaC11:1 5,0 7,8 8,9 7,9

g/L KC11:0 5,0 3,9 4,6 3,2

g/L total de substrat 10,0 11,7 13,5 11,1

g/L N 0,58 0,58 0,58 0,58

Taula 7.2 Taula resum dels resultats obtinguts en els diferents processos en

Figura 7.4 Cromatograma del polímer PHA-F7 obtingut en el cultiu en birreactor. HPR-F7 C9:1+C9:0 C9:1+C9:0 C11:1+C11:0 C7:1+C7:0

RT:12.90 - 27.20

14 16 18 20 22 24 26 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 19.23 19.12 22.11 16.15 16.03 25.93 22.01 23.14 21.63 24.64 18.89 20.70 17.71 13.12 15.41 NL: 4.47E7 TIC MS gceimonica _9 RT:15.79 - 16.44

15.8 15.9 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 16.15 16.03

16.30 16.33 16.38 15.82 15.88 15.96

NL: 1.52E7 TIC M S gceimonica _9 C7:1+C7:0

RT:18.52 - 19.85

18.6 18.8 19.0 19.2 19.4 19.6 19.8 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 19.23 19.12 18.89

18.64 19.56 19.74

NL: 4.47E7 TIC M S gceimonica _9 RT:21.89 - 22.35

21.9 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 22.11 22.01 22.27 21.90 21.93 NL: 1.70E7 TIC M S gceimonica _9 C11:1+C11:0 HPR-F7 C9:1+C9:0 C9:1+C9:0 C11:1+C11:0 C7:1+C7:0

RT:12.90 - 27.20

14 16 18 20 22 24 26 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 19.23 19.12 22.11 16.15 16.03 25.93 22.01 23.14 21.63 24.64 18.89 20.70 17.71 13.12 15.41 NL: 4.47E7 TIC MS gceimonica _9 RT:12.90 - 27.20

14 16 18 20 22 24 26 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 19.23 19.12 22.11 16.15 16.03 25.93 22.01 23.14 21.63 24.64 18.89 20.70 17.71 13.12 15.41 NL: 4.47E7 TIC MS gceimonica _9 RT:15.79 - 16.44

15.8 15.9 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 16.15 16.03

16.30 16.33 16.38 15.82 15.88 15.96

NL: 1.52E7 TIC M S gceimonica _9 C7:1+C7:0

RT:15.79 - 16.44

15.8 15.9 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 16.15 16.03

16.30 16.33 16.38 15.82 15.88 15.96

NL: 1.52E7 TIC M S gceimonica _9 C7:1+C7:0

RT:18.52 - 19.85

18.6 18.8 19.0 19.2 19.4 19.6 19.8 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 19.23 19.12 18.89

18.64 19.56 19.74

NL: 4.47E7 TIC M S gceimonica _9 RT:18.52 - 19.85

18.6 18.8 19.0 19.2 19.4 19.6 19.8 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 19.23 19.12 18.89

18.64 19.56 19.74

NL: 4.47E7 TIC M S gceimonica _9 RT:21.89 - 22.35

21.9 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 22.11 22.01 22.27 21.90 21.93 NL: 1.70E7 TIC M S gceimonica _9 C11:1+C11:0 HPR-F9 C9:1+C9:0 C11:1+C11:0 C7:1+C7:0 C11:1+C11:0 RT:21.86 - 22.41

21.9 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 2 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce RT: 22.03 RT: 22.12 22.26 22.30 21.88 21.94 C9:1+C9:0 RT:18.95 - 19.49

19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce RT: 19.12 RT: 19.23 19.46 RT:15.41 - 22.80

16 17 18 19 20 21 22 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 19.12 19.23 16.04 22.03 16.15 19.56

16.3316.6617.71 18.41 20.49 20.7121.79 NL: 1.48E7 TIC MS gceimonica

_10 C7:1+C7:0

RT:15.76 - 16.43

15.8 15.9 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce RT: 16.04 RT: 16.15 16.33 16.38 15.81 15.9215.97

HPR-F9 C9:1+C9:0 C11:1+C11:0 C7:1+C7:0 HPR-F9 C9:1+C9:0 C11:1+C11:0 C7:1+C7:0 C11:1+C11:0 RT:21.86 - 22.41

21.9 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 2 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce RT: 22.03 RT: 22.12 22.26 22.30 21.88 21.94 C9:1+C9:0 RT:18.95 - 19.49

19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce RT: 19.12 RT: 19.23 19.46 RT:15.41 - 22.80

16 17 18 19 20 21 22 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 19.12 19.23 16.04 22.03 16.15 19.56

16.3316.6617.71 18.41 20.49 20.7121.79 NL: 1.48E7 TIC MS gceimonica

_10 C7:1+C7:0

RT:15.76 - 16.43

15.8 15.9 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce RT: 16.04 RT: 16.15 16.33 16.38 15.81 15.9215.97

C11:1+C11:0 RT:21.86 - 22.41

21.9 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 2 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce RT: 22.03 RT: 22.12 22.26 22.30 21.88 21.94 C9:1+C9:0 RT:18.95 - 19.49

19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce RT: 19.12 RT: 19.23 19.46 C11:1+C11:0 RT:21.86 - 22.41

21.9 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 2 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce RT: 22.03 RT: 22.12 22.26 22.30 21.88 21.94 C11:1+C11:0 RT:21.86 - 22.41

21.9 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 2 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce RT: 22.03 RT: 22.12 22.26 22.30 21.88 21.94 C9:1+C9:0 RT:18.95 - 19.49

19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce RT: 19.12 RT: 19.23 19.46 C9:1+C9:0 RT:18.95 - 19.49

19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce RT: 19.12 RT: 19.23 19.46 RT:15.41 - 22.80

16 17 18 19 20 21 22 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 19.12 19.23 16.04 22.03 16.15 19.56

16.3316.6617.71 18.41 20.49 20.7121.79 NL: 1.48E7 TIC MS gceimonica

_10 C7:1+C7:0

RT:15.76 - 16.43

15.8 15.9 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce RT: 16.04 RT: 16.15 16.33 16.38 15.81 15.9215.97

RT:15.41 - 22.80

16 17 18 19 20 21 22 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 19.12 19.23 16.04 22.03 16.15 19.56

16.3316.6617.71 18.41 20.49 20.7121.79 NL: 1.48E7 TIC MS gceimonica _10 RT:15.41 - 22.80

16 17 18 19 20 21 22 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 19.12 19.23 16.04 22.03 16.15 19.56

16.3316.6617.71 18.41 20.49 20.7121.79 NL: 1.48E7 TIC MS gceimonica

_10 C7:1+C7:0

RT:15.76 - 16.43

15.8 15.9 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce RT: 16.04 RT: 16.15 16.33 16.38 15.81 15.9215.97

C7:1+C7:0 RT:15.76 - 16.43

15.8 15.9 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce RT: 16.04 RT: 16.15 16.33 16.38 15.81 15.9215.97

[image:8.595.135.494.445.721.2]HPR-F10

C9:1+C9:0

C11:1+C11:0 C7:1+C7:0

RT:12.33 - 26.35

14 16 18 20 22 24 26 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 19.12 19.23

16.04 22.04 22.12 16.16

23.14 26.01 16.33 18.41 19.7021.82 25.40 13.25 13.88

C7:1+C7:0 RT:15.45 - 17.10

15.6 15.8 16.0 16.2 16.4 16.6 16.8 17.0 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 16.04 16.16 16.33

16.38 16.5116.59 16.8416.97 15.5315.63 15.8215.95

C9:1+C9:0 RT:18.83 - 19.72

19.0 19.2 19.4 19.6 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 19.12 19.23

19.51 19.55 19.62 18.96

18.90 19.05

C11:1+C11:0 RT:21.76 - 22.52

21.8 21.9 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 2 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 22.04 22.12

22.2922.31 22.40

21.8221.86 22.4

HPR-F10

C9:1+C9:0

C11:1+C11:0 C7:1+C7:0

RT:12.33 - 26.35

14 16 18 20 22 24 26 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 19.12 19.23

16.04 22.04 22.12 16.16

23.14 26.01 16.33 18.41 19.7021.82 25.40 13.25 13.88

C7:1+C7:0 RT:15.45 - 17.10

15.6 15.8 16.0 16.2 16.4 16.6 16.8 17.0 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 16.04 16.16 16.33

16.38 16.5116.59 16.8416.97 15.5315.63 15.8215.95

HPR-F10

C9:1+C9:0

C11:1+C11:0 C7:1+C7:0

RT:12.33 - 26.35

14 16 18 20 22 24 26 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 19.12 19.23

16.04 22.04 22.12 16.16

23.14 26.01 16.33 18.41 19.7021.82 25.40 13.25 13.88

HPR-F10

C9:1+C9:0

C11:1+C11:0 C7:1+C7:0

RT:12.33 - 26.35

14 16 18 20 22 24 26 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 19.12 19.23

16.04 22.04 22.12 16.16

23.14 26.01 16.33 18.41 19.7021.82 25.40 13.25 13.88

C7:1+C7:0 RT:15.45 - 17.10

15.6 15.8 16.0 16.2 16.4 16.6 16.8 17.0 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 16.04 16.16 16.33

16.38 16.5116.59 16.8416.97 15.5315.63 15.8215.95

C7:1+C7:0 RT:15.45 - 17.10

15.6 15.8 16.0 16.2 16.4 16.6 16.8 17.0 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 16.04 16.16 16.33

16.38 16.5116.59 16.8416.97 15.5315.63 15.8215.95

C9:1+C9:0 RT:18.83 - 19.72

19.0 19.2 19.4 19.6 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 19.12 19.23

19.51 19.55 19.62 18.96

18.90 19.05

C11:1+C11:0 RT:21.76 - 22.52

21.8 21.9 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 2 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 22.04 22.12

22.2922.31 22.40

21.8221.86 22.4

C9:1+C9:0 RT:18.83 - 19.72

19.0 19.2 19.4 19.6 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 19.12 19.23

19.51 19.55 19.62 18.96

18.90 19.05

C9:1+C9:0 RT:18.83 - 19.72

19.0 19.2 19.4 19.6 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bun dan ce 19.12 19.23

19.51 19.55 19.62 18.96

18.90 19.05

C11:1+C11:0 RT:21.76 - 22.52

21.8 21.9 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 2 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 22.04 22.12

22.2922.31 22.40

21.8221.86 22.4

C11:1+C11:0 RT:21.76 - 22.52

21.8 21.9 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 2 Time (min) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 R el at iv e A bund an ce 22.04 22.12

22.2922.31 22.40

[image:9.595.142.499.113.385.2]21.8221.86 22.4

Figura 7.6. Cromatograma del polímer PHA-F10 obtingut en el cultiu en

birreactor.

RT:21.12 - 23.34

21.5 22.0 22.5 23.0 Time (min) 0 50 100 0 50 100 R el at iv e A bund anc e 0 50 100 RT: 22.04 MA: 13208615 23.14 22.29 22.40 21.82 21.70

21.27 21.51 22.60 22.83

RT: 22.03 MA: 562054

22.19 22.31 22.51 22.71 23.15 23.27 21.60

21.36 21.68

RT: 22.12 MA: 345109

22.03 22.30 22.38 22.70 23.0023.14 21.78

21.37 21.53

NL: 1.78E6 TIC MS gceimonica_1 1 NL: 1.12E5 m/z= 270.5-271.5 MS gceimonica_1 1 NL: 7.90E4 m/z= 272.5-273.5 MS gceimonica_1 1

Figura 7.7 Análisis de SIM per a la parella monomérica

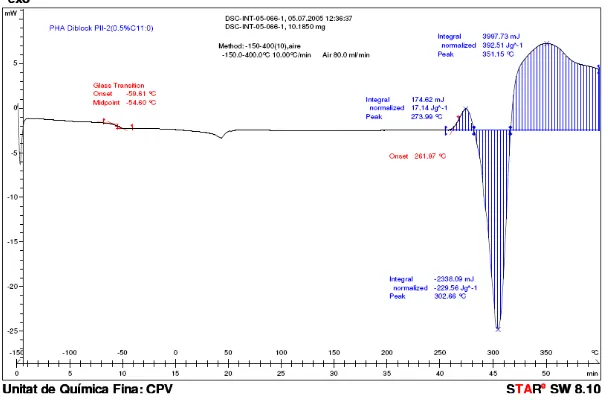

[image:9.595.180.454.463.666.2]Figura 7.8 DSC del PHA-(C11:1+C11:0) obtingut en condicions de cultiu proliferants

Figura 7.9 DSC del PHA-(C11:1+C11:0) obtingut en condicions de

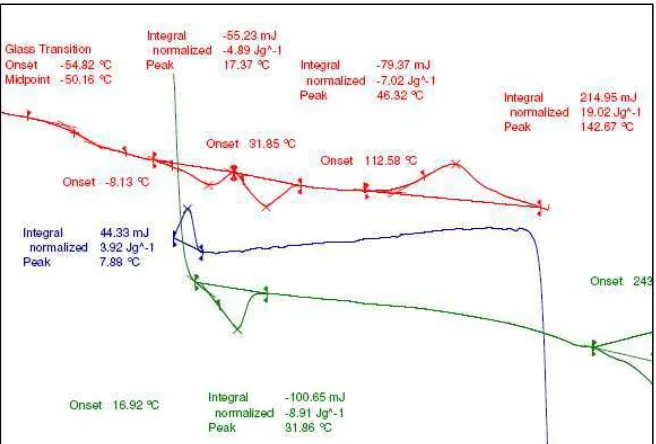

[image:10.595.164.468.568.766.2]Figura 7.11. DSC. Experiment fusió-cristalització-fusió de la part soluble del film de PHA irradiat 24 h amb llum ultravioleta.

Figura 7.12 DRX. Espectro de difracció de raigs X per al polímer natiu PHA-L (línia blava)

[image:11.595.134.518.421.679.2]Facultat de Farmàcia

Departament de Microbiologia i Parasitologia Sanitàries

Estudi dels polihidroxialcanoats acumulats per Pseudomonas

aeruginosa

42A2: producció i caracterització

FACULTAT DE FARMÀCIA

Departament de Microbiologia i Parasitologia Sanitàries

Programa de doctorat: Química Orgànica (Facultat de Químiques)

BIENNI 2002-2004

Estudi dels polihidroxialcanoats acumulats per

Pseudomonas

aeruginosa

42A2: producció i caracterització

Memòria presentada per Mònica Bassas i Galià per optar al títol de doctor per la

Universitat de Barcelona

Director/a:

Dra. Àngels Manresa i Presas Dr. Joan LLorens i Llacuna

Doctorand:

Mònica Bassas i Galià

6. BIBLIOGRAFIA

Agbenyega, J. k., M. Claybourn and G. Ellis (1991). "A study of the autoxidation of some unsaturated fatty acid methyl esters using Fourier Transform Raman Spectroscopy." Spectrochimica Acta 47A(9/10): 1375-1388.

Ahimou, F., F. A. Denis, A. Touhami and Y. F. Dufrene (2002). "Probing microbial cell surface charges by atomic force microscopy." Langmuir 18: 9937-9941.

Akita, S., Y. Einaga, Y. Miyaki and H. Fujita (1976). "Solution properties of poly(D-

β

-hydroxybutyrate). 1. Biosynthesis and characterization." Macromolecules 9(5): 774-780.

Álvarez, H. M., F. Mayer, D. Fabritius and A. Steinbüchel (1996). "Formation of intracytoplasmic lipid inclusions by Rhodococcus opacus strain PD630." Archives of Microbiology 165: 377-386.

Álvarez, H. M., O. H. Pucci and A. Steinbüchel (1997). "Lipid storage compounds in marine bacteria." Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 47: 132-139.

Anderson, A. J. and E. A. Dawes (1990). "Ocurrence, metabolism, metabolic role and industrial uses of bacterial polyhydroxyalkaonates." Microbiological Reviews 54(4): 450-472.

Andrade, A. P., P. Neuenschwander, R. Hany, T. Egli and B. Witholt (2002). "Synthesis and Characterization of novel copoly(ester-urethane) containing blocks of Poly-[(R)-3-hydroxyoctanoate] and Poly-[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate]." Macromolecules 35: 4946-4950. Ashby, R., D. Solaiman and T. Foglia (2002). "The synthesis of short- and medium-chain-length poly(hydroxyalkanoate) mixtures from glucose -or alkanoic acid- grown

Pseudomonas oleovorans." Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology 28:

147-153.

Ashby, R. D., A. Cromwick and T. A. Foglia (1998). "Radiation crosslinking of a bacterial medium-chain-length poly(hydroxyalkanoate) elastomer from tallow." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 23: 61-72.

Ashby, R. D., T. A. Foglia, C.-K. Liu and J. W. Hampson (1998). "Improved film properties of radiation treated medium chain length poly(hydroxyalkanoates)." Biotechnology Letters 20(11): 1047-1052.

Ashby, R. D., T. A. Foglia, D. K. Y. Solaiman, C.-K. Liu, A. Núñez and G. Eggink (2000). "Viscoelastic properties of linseed oil-based medium-chain-lenght poly(hydroxyalkanoate) films: Effects of epoxidation and curing." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 27: 355-368.

Barbuzzi, T., M. Giuffrida, S. Carnazza, A. Ferreri, S. P. P. Gugliemino and A. Ballistreri (2004). "Microbial Synthesis of Poly(3-hydroxyaklanoates) by Pseudomonas

aeruginosa from fatty acids: Identification of higher monomer units and structural

characterization." Biomacromolecules 5: 2469-2478.

Bassas, M., E. Rodríguez, J. Llorens and À. Manresa (2006). "Poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) produced from Pseudomonas aeruginosa 42A2 (NCBIM 40045): Effect of fatty acid nature as nutrient." Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 352: 2243-2247.

Bear, M. M., Leboucher-Durand, M.A., Langlois, V., Lenz, R.W., Goodwin,S. and Guerin, P. (1997). "Bacterial poly-3-hydroxyalkenoates with epoxy groups in the side chains." Reactive and Functional polymers 34: 65-67.

Binning, G., C. F. Quate and C. Gerber (1986). "Atomic force microscopy." Phys. Rev. Lett. 15: 930-933.

Bolshakova, A. V., O. I. Kiselyova and I. V. Yaminsky (2004). "Microbial surfaces investigated using atomic force microscopy." Biotechnology Progress 20(6): 1615-1622.

Boopathy, R. (2000). "Factor limiting bioremediation technologies." Bioresource Technology 74: 63-67.

Brandl, H., R. A. Gross, R. W. Lenz and R. C. Fuller (1988). "Pseudomonas oleovorans

as a source of poly(β-hydorxyalkanoates) for potential application as biodegradable polyester." Applied and Environmental Microbiology 54: 1977-1982.

Cabellos, A. (2003). "Obtención y Caracterización del biopolímero producido por Pseudomonas aeruginsa 42A2 a partir de ácido undecanoico." Proyecto Final de Carrera. Ingenieria Química. Universitat de Barcelona.

Casini, E., C. de Rijk, P. de Waard and G. Eggink (1997). "Synthesis of Poly(hydroxyaklanoate) from Hydrolyzed Linseed Oil." Journal of Environmental Polymer Degradation. 5(3): 153-158.

Cromwick, A., T. Foglia and R. W. Lenz (1996). "The microbial production of poly(hydroxyalkanoates) from tallow." Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 46: 464-469.

Culleré, J. (2002). "Utilització de l'àcid oleic per Pseudomonas sp.42A2." Tesis Doctoral. Universitat de Barcelona.

Culleré, J., O. Durany, M. Busquets and À. Manresa (2001). "Biotransformation of oleic acid into (E)-10-hydroxy-8-octadecenoic acid and (E)-7,10-dihydroxy-8-octadecenoic acid by Pseudomonas sp.42A2 in an immobilized system." Biotechnology Letters 23: 215-219.

Choi, J.-I. and S. Y. Lee (1999). "High-level production of poly-(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) by fed-batch culture of recombinant Escherichia coli." Applied and Environmental Microbiology 65(10): 4363-4368.

Dawes, E. A. (1973). "The role and regulation of energy reserve polymers in microorganisms." Adv. Microb. Physiol. 10: 135-266.

De Koning, G. (1995). "Physical properties of bacterial poly((R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates)." Can. J. Microbiol. 41(suppl.1): 303-309.

De Koning, G. J. M., M. Kellerhals, C. van Meurs and Witholt, B. (1997a). "A process for the recovery of poly(hydroxyalkanoates) from Pseudomonads Part 2: Process development and economic evaluation." Bioprocess Engineering 17: 15-21.

De Koning, G. J. M., Witholt, B. (1997b). "A process for the recovery of poly(hydroxyalkanoates) from Pseudomonads. Part 1: Solubilization." Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering 17: 7-13.

De Smet, M. J., G. Eggink, B. Witholt, J. Kingma and H. Wynberg (1983). "Characterization of intracellular inclusions formed by Pseudomonas oleovorans during growth on octane." Journal of Bacteriology 154(2): 870-878.

De Waard, P., H. van der Wal, G. M. N. Huijberts and G. Eggink (1993). "Heteronuclear NMR analysis of unsaturated fatty acids in poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates)." The Journal of Biological Chemistry 268(1): 315-319.

Dennis, D., Liebig, C., Holley, t. and al. (2003). "Preliminary analysis of polyhydroxyalkanoate inclusions using atomic force microscopy." FEMS Microbiology Letters 226: 113-119.

Doi, Y. and C. Abe (1990). "Biosynthesis and characterization of a new bacterial copolyester of 3-hydroxy-ω−chloroalkenoates." Macromolecules 23: 3703-3707.

Du, G. and J. Yu (2002). "Green Technology for Conversion of Food Scraps to Biodegradable Thermoplastic Polyhydroxyalkanoates." Environ. Sci. Technol. 36: 5511-5516.

Dufresne, A., L. Reche, R. H. Marchessault and M. Lacroix (2001). "Gamma-ray crosslinking of poly(3-hydroxyoctanoate-co-undecenoate)." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 29: 73-82.

Eggink, G., P. de Waard and G. N. M. Huijberts (1995). "Formation of novel poly(hydroxyalkanoates) from long-chain fatty acids." Canadian Journal of Microbiology 41 (suppl 1): 14-21.

esters trimethylsilyl ethers of aliphatic hydroxy acids. A facile method of double bond location." Org. Mass Spec. 1: 593-611.

El Kirat, K., I. Burton, V. Dupres and D. Y.F (2005). "Sample preparation procedures for biologiacal atomic force microscopy." Journal of Microscopy 219(3): 199-207. Fernández, D. (2000). "Producción y caracterización de los polihidroxialcanoatos producidos por Pseudomonas sp. 42A2." Máster Experimental en Biologia. Universitat de Barcelona.

Fernández, D., E. Rodríguez, M. Bassas, M. Viñas, A. M. Solanas, J. Llorens, M. A.M. and A. Manresa (2005). "Agro-industrial oily wastes as substrates for PHA production by the new strain Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIB 40045: Effect of culture conditions." Biochemical Engineering Journal 26(2-3): 159-167.

Fernandez del Castillo, R., F. Rodriguez Valera, J. Gonzalez Ramos and F. Ruiz Berraquero (1986). "Accumulation of Poly(β-Hydroxybutyrate) by Halobacteria." Applied and Environmental Microbiology 51(1): 214-216.

Fiedler, S., A. Steinbüchel and B. Rehm (2002). "The role of the fatty acid b-oxidation multienzyme complex from Pseudomonas oleovorans in polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis: molecular characterization of the fadBA operon from P.oleovorans and of the enoyl-CoA hydratase genes phaJ from P.oleovorans and Pseudomonas putida." Arch Microbiol 178: 149-160.

Findlay, R. H. and D. C. White (1983). "Polymeric β-hydroxyalkanoates from environmental samples and Bacillus megaterium." Applied and Environmental Microbiology 45(1): 71.

Flechter, A. (1993). "Plastics from Bacteria and for Bacteria: PHA as Natural, Biodegradable Polyesters." Springer Verlag, New York: 77-93.

Fritzsche, K., R. W. Lenz and R. C. Fuller (1990). "Bacterial polyesters containing branched poly (β-hydroxyalkanoate) units." J. Biol. Macromol Chem. 191: 92-101. Fritzsche, K., R. W. Lenz and R. C. Fuller (1990). "An unnusual bacterial polyester with a phenyl pendant group." Macromol. Chem. 191: 1957-1965.

Fukui, T., M. Kato and H. Matsusaki (1998). "Morphological and 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance studies for polyhydroxyalkanoates biosynthesis in Pseudomonas sp.61-3." FEMS Microbiology Letters 164: 219-225.

Furrer, P., R. Hany, D. Rentsch, A. Grubelnik, K. Ruth, S. Pake and M. Zinn (2007). "Quantitative analysis of bacterial medium-chain-length pol([R]-3-hydroxyalkanoates) by gas chromatography." Journal of Chromatography A 1143: 199-206.

Gerngross, T. U., P. Reilly, P. Stubbe, A. J. Sinskey and O. P. Peoples (1993). "Immunocytochemical analysis of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) synthase in

Alcaligenes eutrophus H16: localization of the synthase enzyme at the surface of

PHB-granules." Journal of Bacteriology 175: 5289-5293.

Gogolewski, S., M. Jovanovic, S. M. Perren, J. G. Dillon and M. K. Hughes (1993). "Tissue response and in vivo degradation of selected polyhydroxyacids: polylactides (PLA), poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHB/VA)." Journal of biomedical materials research 27(9): 1135-1148.

Gorenflo, V., A. Steinbüchel, S. Marose, M. Reiseberg and T. Scheper (1999). "Quantification of bacterial polyhydroxyalkaonoic acids by Nile red staining." Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 51: 765-772.

Griebel, R., Z. Smith and J. M. Merrick (1968). "Metabolism of poly-β -hydroxyabutyrate granules from Bacillus megaterium." Biochemistry 7: 3676-3681. Gross, R. A., C. DeMello and R. W. Lenz (1989). "Biosynthesis and characterization of poly(β-hydroxyalkanoates) produced by Pseudomonas oleovorans." Macromolecules 22: 1106-1115.

Guerrero, A., I. Casals, M. Busquets, Y. León and A. Manresa (1997). "Oxidation of oleic acid to (E)-10-hydroperoxy-8-octadecenoic acid and (E)-10-hydroxy-8-ocatadecenoic acids by Pseudomonas sp. 42A2." Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1347: 75-81.

Haba, E., J. Vidal-Mas, M. Bassas, M. J. Espuny, J. Llorens and A. Manresa (2007). "Poly 3-(hydroxyalkanoates) produced from oily substrates by Pseudomonas

aeruginosa 47T2 (NCBIM 40044): Effect of nutrients and incubation temperature on

polymer composition." Biochem. Eng. J. 35(2): 99-106.

Handrick, R., S. Reinhardt and D. Jendrossek (2000). "Mobilization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) in Ralstonia eutropha." Journal of Bacteriology 182(20).

Hanley, S., D. J. C. Pappin, D. Rahman, A. j. White, K. M. Elborough and A. R. Slabs (1999). "Re-evaluation of the primary structure of Ralstonia eutropha phasin and implications for polyhidroxyalkanoic acid granule binding." FEBS Lett. 447: 99-105. Hartmann, R. (2005). "Tailored Medium-Chain-Length Poly[(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates]: Biosynthetic and Chemical Approaches." Tesis Doctoral. Swiss Federal Institute of Technology of Zurich.

Hartmann, R., R. Hany, T. geiger, T. Egli, B. Witholt and M. Zinn (2004). "Tailored biosynthesis of olefinic medium-chain-length poly[(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates] in

Pseudomonas putida GPo1 with improved thermal properties." Macromolecules 37:

3780-6785.

Hernández, R. (2003). "Utilización de ácidos alcanoicos (C5-C9) para la obtención de

polihidroxialcanoatos mediante Pseudomonas aeruginosa 42A2." Proyecto Final de Carrera. Ingenieria Química. Universitat de Barcelona.

T. Hiraishi, Y. Kikkawa, M. Fujita, N. Mohd, M. Kanesato, K. Tsuge, M. Maeda and Y. Doi (2005). "Atomic force microscopic observation of in vitro polymerized poly[(R)-hydroxybutyrate]: insight into possible mechanisms of granule formation." Biomacromolecules 6: 2671-2677.

Hirt, T. D., P. Neuenschwander and U. W. Suter (1996a). "Synthesis of degradable, biocompatible, and tough block-copolyesterurethanes." Macromol. Chem. Phy. 197: 4253-4268.

Hirt, T. D., P. Neuenschwander and U. W. Suter (1996b). "Telechelic diols from poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyric acid] and poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyric acid]-co-poly[(R)-3-hydroxyvaleric acid]." Macromol. Chem. Phy. 197: 1609-1614.

Hori, K., K. Soga and Y. Doi (1994). "Production of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates-co-3-hydroxy-ω-fluoroalkanoates) by Pseudomonas oleovorans from 1-fluorononane and glucomate." Biotechnology Letters 16(5): 501.

Huijberts, G. N., G. Eggink, P. Waard, G. W. Huisman and B. Witholt (1992). "Pseudomonas putida KT2442 cultivated on glucose accumulates poly(3- hydroxyalkanoates) consisting of saturated and unsaturated monomers." Applied and Environmental Microbiology 58(2): 536-544.

Huijberts, G. N. M. and G. Eggink (1996). "Production of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates)

by Pseudomonas putida KT2442 in continuous cultures." Applied Microbiology and

Biotechnology 46: 233-239.

Huisman, G. W., O. Leeuw, G. Eggink and B. Witholt (1989). "Synthesis of poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates is a common feature of fluorescent Pseudomonads." Applied and Environmental Microbiology 55(8): 1949-1954.

Johnstone, B. (1990). "A throw away answer." Far Eastern Econ. Rev. 147(6): 62-63. Jung, Y. M., J. S. Park and Y. H. Lee (2000). "Metabolic engineering of Alcaligenes

eutrophus through the transformation of cloned phvCAB genes for the investigation of

the regulatory mechanism of polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis." Enzyme and Microbial Technology 26: 201-208.

Jurasek, L., Marchessault (2004). "Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) granule formation in

Ralstonia eutropha cells: a computer simulation." Applied Microbiology and

Biotechnology 64: 611-617.

Kadouri, D., E. Jurkevitch and Y. Okon (2005). "Ecological and Agricultural Significance of Bacterial Polyhydroxyalkanoates." Critical Reviews in Microbiology 31: 55-67.

Kelley, A. S. and F. Srienc (1999). "Production of two phase polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules in Ralstonia eutropha." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 25: 61-67.

Kidwell, P. A. and K. Bleman (1982). "Determination of double bond position and geometry of olefins by mass spectrometry of their Diels-Alder adducts." Anal. Chem. 54: 2462-2465.

Kim, B. S. (2000). "Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) from inexpensive substrates." Enzyme an Microbial Technology 27: 774-777.

Kim, B. S. (2002). "Production of medium chain lenght polyhydroxyalkanoates by fed-batch culture of Pseudomnas oleovorans." Biotechnol Lett. 24: 125-130.

Kim, B. S. and H. N. Chang (1998). "Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) from starch by Azotobacter chroococcum." Biotechnology Letters 20(2): 109-112.

Kim, D. Y., S. B. Jung, G. G. Choi, Y. B. Kim and Y. H. Rhee (2001). "Biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate copolyester containing cyclohexyl groups by Pseudomonas oleovorans." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 29: 145-150.

Kim, D. Y., Y. B. Kim and Y. H. Rhee (1998). "Bacterial poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) bearing carbon-carbon triple bonds." Macromolecules 31: 4760-4763.

Kim, D. Y., Y. B. Kim and Y. H. Rhee (2000). "Evaluation of various carbon substrates for the biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates bearing functional groups by

Pseudomonas putida." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 28: 23-29. Kim, H. W., G. H.W. and C. T. Hou (2000). Production of isomeric 9,10,13 (9,12,13)-trihidrydroxy-11-E-(10E)-octadecenoic acid from linoleic acid by Pseudomonas

aerugiosa PR3. 25: 109-115.

Kim, O., R. A. Gross and D. R. Rutherford (1995). "Bioengineering of poly(β -hydroxyalkanoates) for advanced material applications: incorporation of cyano and nitrophenoxy side chain substituents." Canadian J. Microbiol 41(suppl.1): 32.

Kim, Y. B. and R. W. Lenz (2001). "Polyesters from microorganism." Advances in biochemical Engineering Biotechnology 71: 52.

Kim, Y. B., R. W. Lenz and R. C. Fuller (1992). "Poly(b-hydroxyalkanoate) copolymers containing brominated repeating units produced by Pseudomonas oleovorans." Macromolecules 25: 2852-2857.

Koritala, S. and M. O. Bagby (1992). "Microbial Conversions of Linoleic and Linolenic Acids to Unsaturated Hydroxy Fatty Acids." JAOCS 69(6): 575-578.

Kumar, N. and M. N. V. Ravikumar (2001). "Biodegradable block coploymer." Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 53: 23-44.

Kunioka, M., Y. Kawaguchi and Y. Doi (1989). "Production of biodegradable copolyestes of 3-hydroxybutyrate and 4-hydroxybutyrate by Alcaligenes eutrophus." Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 30: 569-573.

Kunststoffe (2004). "Oktober Ausgabe. Carl Hanser Verlag, München."

Kuo, T. M., L. K. Manthey and C. T. Hou (1998). "Fatty acid bioconversions by

Pseudomonas aeruginosa PR3." JAOCS 75(7): 875-879.

Kurth, N., Renard, E., Brachet, F., Robic, D., Guerin, PH., Bourbouze, R. (2002). "Poly(hydroxyoctanoate) containing pendant carboxylic groups for the preparation of nanoparticles aimed at drug transport and release." Polymer 43: 1095-1101.

Lageveen, R. G. B., G. W. Huisman, H. Preusting, P. Ketelar, G. Eggink and Witholt (1988). "Formation of polyesters by Pseudomonas oleovorans: Effect of the substrates on formation and composition of poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates and poly-(R )-3-hydroxyalkenoates." Applied and Environmental Microbiology 54: 2924-2932.

Lazzari, M. a. C., O. (1999). "Drying and oxidative degradation of linseed oil." Polymer Degradation and Stability 65: 303-313.

Lee, E.-Y. and C.-Y. Choi (1995). "Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometric Analysis and Its Application to a Screening Procedure for Novel Bacterial Polyhydroxyalkanoic Acids Containing Long Chain Saturated and Unsaturated Monomers." Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering 80(4): 408-414.

Lee, M. Y., W. H. Park and R. W. Lenz (2000). "Hydrophilic bacterial polyesters modified with pendant hydroxyl groups." Polymer 41: 1703-1709.

Lee, S. Y. (1996). "Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates." Biotechnology and Bioengineering 49: 1-14.

Lee, S. Y. (1996). "Plastic bacteria? Progress and prospects for polyhydroxyalkanoate production in bacteria." TIBTECH 14: 431-438.

Lee, S. Y. (1999). "Chiral compounds from bacterial polyesters: Sugars to plastics to fine chemicals." Biotechnology and Bioengineering 65: 363.

Lee, S. Y., J. I. Choi and H. H. Wong (1999). "Recent advances in polyhydroxyalkanoate production by bacterial fermentation: mini-review." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 25: 31-36.

Madison, L. L. and G. W. Huisman (1999). "Metabolic engineering of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates): from DNA to plastic." Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 63(1): 21-53.

Maehara, A., Y. Doi, Z. Nishiyama, Y. Takagi, S. Ueda, S. Nakano and T. Yamane (2001). "PhaR: a protein of unknown function conserved among short-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoic acids producing bacteria, is a DNA-binding protein and represses

Paracoccus denitrificans phaP expression in vitro." FEMS Microbiology Letters 200: 9-15.

Mallégol, J., L. Gonon, J. Lemaire and J.-L. Gardette (2001). "Long-term behaviour of oil-based varnishes and paints. 4. Influence of film thickness on the photooxidation." Polymer Degradation and Stability 72: 191-197.

Matsumoto, K., Matsusaki, H., Taguchi, K., Seki, M. and Doi, Y. (2002). "Isolation and characterization of polyhydroxyalkanoates inclusions and their associated proteins in

Pseudomonas sp.61-3." Biomacromolecules 3: 787-792.

Marqués, A. M. (1982). "Aislamiento y caracterización de Pseudomonas aeruginosa

procedentes de distintos hábitats: Aspectos ecológicos y sanitários." Tesis Doctoral. Departament de Microbiologia i Parasitologia Sanitàries. Facultat de Farmàcia. Universitat de Barcelona.

McCloskey, J. A. (1969). "Mass spectrometry of lipids and steroids." Methods of Enzimology 14: 382-450.

Moore, C. J., S. L. Moore, M. K. Leecaster and S. B. Weisberg (2001). "A comparision of plastic and plankton in the North Pacific Central Gyre." Marine Pollution Bulletin 49: 1298-1300.

Numata, K., Y. Kikkawa, T. Tsuge, T. Iwata, Y. Doi and H. Abe (2005). "Enzymatic degradation processes of hydroxybutyric acid] and poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyric acid-co-(R)-3-hydroyvaleric acid] single crystals revealed by atomic force microscopy: effect of molecular weight and the second monomer composition on erosion rates." Biomacromolecules 6: 2008-2016.

Nuñez, M. J., M. O. Martin, P. H. Chan, L.-K. Duonog and A. R. Sindhurakar (2005). "Atomic force microscopy of bacterial communities in Environmental Microbiology." AC. Press.

Page, W. J. (1992). "Suitability of commercial beet molasses fractions as substrates for polyhydroxyalkanoate production by Azotobacter vinelandii UWD." Biotechnology Letters 14(5): 385-390.

Park, J.S., H. C. Park, T. L. Huh and Y. H. Lee (1995). "Production of poly-β -hydroxybutyrate by Alcaligenes eutrophus transformants harbouring cloned phbCAB genes." Biotechnology Letters 17(7): 735-740.

Peters, V. and B. H. A. Rehm (2005). "In vivo monitoring of PHA granule formation using GFP-labeled PHA synthases." FEMS Microbiology Letters 248: 93-100.

Philip, S., T. Keshavarz and I. Roy (2007). "Review. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: biodegradable polymers with a range of applications." Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 82: 233-247.

Pieper-Fürst, U., M. H. Madkour, F. Mayer and A. Steinbüchel (1994). "Purification and characterization of a 14-kilodalton protein that is bound to the surface of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules in Rhodococcus ruber." Journal of Bacteriology 176: 4328-4337.

Pötter, M., M. H. Madkour, F. Mayer and A. Steinbüchel (2002). "Regulation of phasin expression and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) granule formation in Ralstonia eutropha

H16." Microbiol. 148: 2413-2426.

Pretsch, E., J. Seibl and W. Simon (1998). "Tablas para la determinación structural por métodos espectroscópicos." Springer -Verlag Ibérica.

Preusting, H., W. Hazenberg and B. Witholt (1993). "Continuous production of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates by Pseudomonas oleovorans in a high-cell-density two-liquid-phase chemostat." Enzyme microbial Technology 15(April): 311-316.

Preusting, H., Nijenhuis,A., and Witholt, B. (1990). "Physical Characteristics of Poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) and Poly(3-Poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) produced by Pseudomonas oleovorans grown on aliphatic hydrocarbons." Macromolecules 23: 4220-4224.

Prieto, M. A., B. Bühler, K. Jung, B. Witholt and B. Kessler (1999). "PhaF, a polyhydroxyalkanoate-granule-associated protein od Pseudomonas oleovorans Gpo1 involved in the regulatory expression system for pha Genes." Journal of Bacteriology 181(3): 858-868.

Reddy, C. S. K., R. Ghai and K. V. C. Rashmi (2003). "Polyhydroxyalkanoates: an overview." Bioresource Technology 87: 137-146.

Rehm, B., N. Krüger and A. Steinbüchel (1998). "A new metabolic link between fatty acid de novo synthesis and polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthesis." The Jounal of Biological Chemistry 273, No.37(11): 24044-24051.

Rehm, B. H. A. (2006). "Genetics and biochemistry of polyhydroxyalkanoate granule self-assembly: The key role of polyester synthases." Biotechnology Letters 28: 207-213.

Rehm, B. H. A. and A. Steinbüchel (1999). "Biochemical and genetic analysis of PHA synthases and other proteins required for PHA synthesis." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 25: 3-19.

Renard, E., Walls, M., Guerin, P and Langlois V. (2004). "Hydrolytic degradation of blends of polyhydroxyalkanoates and functionalized polyhydroxyalkanoates." Polymer Degradation and Stability 85: 779-787.

Reynolds, E. S. (1963). "The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electron opaque strain in electron microscopy." J. Cel. Bio. 17: 208-212.

Robert, M. (1989). "Aislamiento y selección de microorganismos productores de tensioactivos. Producción y caracterización de biotensioactivos por Pseudomonas

44T1." Departamento de Microbiologia Facultad de Farmacia. Barcelona, Barcelona. Rodríguez, E. (2006). "Aplicación de la Metodología de Superfícies de Respuesta den matraces y estratégias de producción en bioreactor para la obtención de biomasa y polihidroxialcanoatos por Pseudomonas aeruginosa 42A2." Tesis Doctoral. Universitat de Barcelona.

Rossini, C., J. Arceo, E. McCarney, B. Augustine, D. Dennis, M. D. Flythe and S. F. baron (2001). "Use of in situ atomic force microscopy to monitor the biodegradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs)." Macromol Symp 167: 139-151.

Ruth, K., A. Grubelnik, R. Hartmann, T. Egli, M. Zinn and Q. Ren (2007). "Efficient production of (R)-3-hydroxycarboxylic acids by biotechnological conversion of Polyhydroxyalkanoates and their purification." Biomacromolecules 8(1): 279-286.

Saad, B., P. Neuenschwander, G. K. Uhlsmitd and U. W. Suter (1999). "New versatile, elastomeric, degradable polymeric materials for medicine." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 25: 293-301.

Saegusa, H., K. M. Shiraki, C. Kanai and T. Saito (2001). "Cloning of an intracellular poly[D8-)-3-hydroxybutyrate] depolymerase gene from Ralstonia eutropha H16 and characterization of the gene product." Journal of Bacteriology 183: 94-100.

Schmid, M., A. Ritter, A. Grubelnik and M. Zinn (2006). "Autoxidation of Medium Chain Length Polyhydroxyalkanoate." Biomacromolecules 8(2): 579-584.

Solaiman, D. K. Y., R. D. Ashby and T. A. Foglia (1999). "Medium-Chain-Length poly(β-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis from triacylglycerols by Pseudomonas saccharophila." Current Microbiology 38: 151-154.

Song, J. J., S. C. Yoon, S. M. Yu and R. W. Lenz (1998). "Differential scanning calorimetric study of poly(3-hydroxyoctanoate) inclusions in bacterial cells." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 23: 165-173.

Spurr, A. R. (1969). "A low-viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy." J. Ultrastruct. Res. 26: 31.

Steinbüchel, A. (2001). "Prespectives for Biotechnological Production and Utilitzation of Biopolymer: Metabolic Engineering of Polyhydroxyalkanoates Biosynthesis Pathways as a sucessful example." Macromol Biosci. 1: 1-24.

bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoic acid inclusions." Canadian J. Microbiol (Suppl-1) 41(1): 94-105.

Steinbüchel, A. and B. Füchtenbusch (1998). "Bacterial and other biological systems for polyester production." Trends in Biotechnology (TIBTECH) 16: 419-427.

Steinbüchel, A. and P. Schubert (1989). "Expression of the Alcaligenes eutrophus

poly(β-hydroxybutyric acid)- synthetic pathway in Pseudomonas sp." Archives of Microbiology 153: 101-104.

Steinbüchel, A. and H. E. Valentin (1995). "Diversity of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoic acids." FEMS Microbiology Letters 128: 219-228.

Steinbüchel, A. and S. Wiese (1992). "A Pseudomonas strain accumulating Polyesters of 3-hydroxybutyric acid and Medium-Chain-Length 3-hydroyalkanoic acids." Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 37: 691-697.

Stuart, E. S., R. W. Lenz and R. C. Fuller (1995). "The ordered macromolecular surface of polyester inclusion bodies in Pseudomonas oleovorans." Canadian J. Microbiol 41(suppl.1): 84-93.

Stuart, E. S., A. Tehrani, H. E. Valentin, D. Dennis, R. W. Lenz and R. C. Fuller (1998). "Protein organization on the PHA inclusion cytoplasmic boundary." J. Biotechnol (2-3): 137-144.

Sudesh, K., H. Abe and Y. Doi (2000). "Synthesis, structure and properties of polyhydroxyalkanoates: biological polyesters." Progress in Polymer Science 25: 1503-1555.

Sudesh, K. and Y. Doi (2000). "Molecular Design and Biosynthesis of Biodegradable polyesters." Polymers for adavanced technologies 11: 865-872.

Sudesh, K., Gan, Z., Maehara, A., Doi, Y. (2002). "Suface structure, morphology and stability of polyhydroxyalkanoate inclusions characterised by atomic force microscopy." Polymer Degradation and Stability 77: 77-85.

Takagi, Y., H. Hashii, A. Maehara and T. Yamane (1999). "Biosynthesis of Polyhydroxyalkanoate with a thiophenoxy Side Group Obtained from Pseudomonas putida." Macromolecules 32: 8315-8318.

Tanaka, T., M. Fujita, et al. (2005). "Structure investigation of narrow banded spherulites in polyhydroxyalkanoates by microbeam X-ray difraction with synchrotron radiation." Polymer46: 5673-5679.

Timm, A., S. Wiese and A. Steinbüchel (1994). "A general method for identification of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthase genes from pseudomonads belonging to the rRNA homolgy group I." Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 40: 669-675.

Tokiwa, Y. and T. Suzuki (1977). "Hydrolisis of polyesters by lipases." Nature 270: 76-78.

Ubbink, J. and P. Schär-Zammaretti (2005). "Probing bacterial interactions: integrated approches combining atomic force microscopy, electron microscopy and biophysical techniques,." Micron 36: 293-320.

Valentin, H. E., Y. E. Lee, C. Y. Choi and A. Steinbüchel (1994). "Identification of 4-hydroxyhexanoic acid as a new constituent of biosynthetic polyhydroxyalkanoic acids from bacteria." Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 40: 710-716.

Valentin, H. E., S. Reiser and K. J. Gruys (2000). "Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) formation from γ-Aminobutyrate and glutamate." Biotechnology and Bioengineering 67(3): 291-299.

Valentin, H. E., A. Schönebaum and A. Steinbüchel (1996). "Identificaction of 5-hydroxyhexanoic acid, 4-hydroxyheptanoic acid and 4-hydroxyoctanoic acid as new constituents of bacterial polyhydroxyalkaonic acids." Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 46: 261-267.

van der Walle, G. A., G. J. de Koning, G. Weusthuis and G. Eggink (2001). "Properties, modifications and applications of biopolyesters." Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 71: 263-291.

Van der Walle, G. A. M., G. J. H. Buisman, R. A. Weusthuis and G. Eggink (1999). "Development of environmentally friendly coatings and paints using medium-chain-lenght poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) as the polymer binder." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 25: 123-128.

Wallen, L. L. and W. K. Rohwedder (1974). "Poly-β-hydroxyalkanoates from activated sludge." Environ. Sci. Technol. 8: 576-579.

Wang, J. G. and L. R. Bakken (1998). "Screening of soil bacteia for polybeta-hydroxybutyric acid production and its role in the survival of starvation." Microb. Ecol. 35: 94-101.

Williams, S. F., D. P. Martin, D. M. Horowitz and O. P. Peoples (1999). "PHA applications: addressing the price performance issue I. Tissue engineering." International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 25: 111-121.

Witholt, B. and B. Kessler (1999). "Perspectives of medium chain length poly(hydroxyalkanoates), a versatile set of bacterial bioplastics." Current Opinion in Biotechnology 10: 279-285.

Xu, J., B. H. Guo, et al. (2003). "Terraces on banded spherulites of polyhydroxyalkanotes." Journal of Polymer Science: Part B: Polymer Physics 41: 2128-2134.

York, G. M., B. H. Junker, J. Stubbe and A. J. Sinskey (2001). "Accumulation of the PhaP phasin on Ralstonia eutropha is dependent on porduction of polyhydroxybutyrate in cells." Journal of Bacteriology 183(14): 4217-4226.

York, G. M., J. Stubbe and A. J. Sinskey (2002). "The Ralstonia eutropha PhaR protein couples synthesis of the PhaP phasin to the presence of polyhydroxybutyrate in cells and promotes polyhydroxybutyrate production." Journal of Bacteriology 184: 59-66. Yu, P. H., H. Chua, A. L. Huang, W. Lo and G. Q. Chen (1998). "Conversion of food industrial wastes into bioplastics." Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 70-72: 603-614.

Zinn, M., B. Wiltholt and T. Egli (2001). "Occurrence, synthesis and medical application of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates." Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 53: 5-21.

Facultat de Farmàcia

Departament de Microbiologia i Parasitologia Sanitàries

Estudi dels polihidroxialcanoats acumulats per Pseudomonas

aeruginosa

42A2: producció i caracterització

FACULTAT DE FARMÀCIA

Departament de Microbiologia i Parasitologia Sanitàries

Programa de doctorat: Química Orgànica (Facultat de Químiques)

BIENNI 2002-2004

Estudi dels polihidroxialcanoats acumulats per

Pseudomonas

aeruginosa

42A2: producció i caracterització

Memòria presentada per Mònica Bassas i Galià per optar al títol de doctor per la

Universitat de Barcelona

Director/a:

Dra. Àngels Manresa i Presas Dr. Joan LLorens i Llacuna

Doctorand:

Mònica Bassas i Galià

5. CONCLUSIONS

1. Pseudomonas aeruginosa 42A2 es capaç de créixer i acumular PHA a partir dels

següents substrats: àcid nonanoic, àcid undecanoic, àcid undecenoic, extracte monodi, àcid linoleic i oli de llinosa.

2. La composició monomèrica del polièster obtingut a partir dels substrat monodi no reflecteix la composició del substrat.

3. Quan P. aeruginosa 42A2 es fa créixer en oli de llinosa com substrat s’obté un PHA altament funcionalitzat que conté un 16% d’unitats monomèriques poliinsaturades (8,3% de C14:3 i 7,6% de (C14:2+C12:2).

4. La irradiació amb llum UV del PHA-L, obtingut a partir d’oli de llinosa, indueix l’entrecreuament de les cadenes laterals del polímer generant un nou material. El canvi estructural degut a la reacció d’entrecreuament ha estat verificats per microscòpia de força atòmica (AFM), tal i com ho mostren les imatges, essent la primera vegada que es recullen imatges d’un polihidroxialcanoat reticulat..

5. El règim d’alimentació continu en els cultius en bioreactor permet modular la composició del polímer i augmentar el percentatge d’acumulació fins a un 50% en el cas dels cultius alimentats amb àcid undecenoic i àcid undecanoic.

6. Quan s’utilitza àcid undecenoic i àcid undecanoic com a font de carboni, P.

aeruginosa sintetitza un copolímer que conté entre un 15-70% de monòmers insaturats

Facultat de Farmàcia

Departament de Microbiologia i Parasitologia Sanitàries

Estudi dels polihidroxialcanoats acumulats per Pseudomonas

aeruginosa

42A2: producció i caracterització

FACULTAT DE FARMÀCIA

Departament de Microbiologia i Parasitologia Sanitàries

Programa de doctorat: Química Orgànica (Facultat de Químiques)

BIENNI 2002-2004

Estudi dels polihidroxialcanoats acumulats per

Pseudomonas

aeruginosa

42A2: producció i caracterització

Memòria presentada per Mònica Bassas i Galià per optar al títol de doctor per la

Universitat de Barcelona

Director/a:

Dra. Àngels Manresa i Presas Dr. Joan LLorens i Llacuna

Doctorand:

Mònica Bassas i Galià

4. RESULTATS I DISCUSSIÓ

4.1. Fonts de carboni complexes

Al llarg de la última dècada s’han emprat múltiples espècies de Pseudomonas per a la producció de PHA de cadena mitja a partir d’una gran varietat de fonts de carboni d’origen agrícola (Eggink et al., 1992), (Huisman et al., 1989). Els àcids grassos procedents d’olis vegetals, tals com l’àcid làuric, l’àcid mirístic, l’àcid palmític, l’àcid esteàric o l’àcid oleic han estat els més emprats no tan sols per la seva abundància sinó també pel seu relatiu baix cost (De Waard et al., 1993). La majoria d’aquests àcids grassos es troben en forma de mescles en residus industrials derivats de la producció de d’olis vegetals.

Tant l’oleïna (àcid oleic tècnic) com el weichol són productes industrials rics en àcid oleic (60-70 % (p/p)) que s’han emprat com a substrat en diferents estudis de biotransformacions de residus oleaginosos en cultius de P. aeruginosa 42A2 (Culleré, 2002) així com també en l’optimització de cultius d’alta densitat (Rodríguez, 2006). Aquests substrats també han estat utilitzats en la producció de polihidroxialcanoats. D’acord amb el resultats obtinguts per Fernández et al. (Fernández, 2000), quan es fa créixer la P. aeruginosa 42A2 en medi mineral mínim (MM1) amb 20 g/L d’oleïna, agitació (120 rpm) i 30ºC, la màxima producció de biomassa i PHA es produeix a les 72 h de cultiu obtenint 4,4 i 2,3 g/L de biomassa i de PHA, respectivament. Aquests valors representen una acumulació de PHA del 53 % (p/p). De tots els substrats assajats i descrits a l’apartat 3.2.1.2 de material i mètodes, per aquest treball s’ha descartat l’oli de fusta (tung oil) ja que presentava rendiments molt baixos de producció de PHA.

4.1.1 Cultius i producció de PHA amb substrats complexos

4.1.1.1 Extracte pasta monodi (oli monodi)

En treballs realitzat anteriorment s’han descrit fins a tres productes extracel·lulars resultants de la biotransformació de l’àcid oleic quan es emprat com a substrat en cultius

de P. aeruginosa 42A2. Els productes foren identificats com a: àcid

Tal i com s’explica a l’apartat 3.2.1.2, a l’acidificar el sobrenedant d’un cultiu on s’ha emprat l’àcid oleic com a font de carboni, s’obtenen aquests productes en forma d’un precipitat blanc després de 24 h a 4 ºC. A aquest precipitat se l’ha denominat “pasta”. Després de l’extracció de la pasta amb cloroform s’obté un oli que conté principalment àcid oleic i dos dels productes de biotransformació abans esmentats, MHOD i DHOD, ja que el tercer compost que es forma, l’hidroperoxi (HOOD), s’hidrolitza en el medi de cultiu com a conseqüència de la precipitació àcida i es transforma ràpidament en el derivat monohidroxilat (Guerrero et al., 1997).

La Figura 4.1 mostra la composició de l’oli obtingut a partir de l’extracció de la pasta amb cloroform. Tal i com es pot veure, aquest oli està constituït principalment per restes d’àcid oleic, pel derivat monohidroxilat (MHOD) i pel derivat dihidroxilat (DHOD).

[image:38.595.149.461.373.545.2]Degut a les característiques estructurals d’aquests productes, que contenen grups hidroxil i una insaturació al mig de la cadena, es va creure interessant emprar-los com a font de carboni per a la producció de PHAs funcionalitzats. Amb aquest objectiu es van provar diferents estratègies de cultiu: cultius discontinus, cultius alimentats i cultius en condicions no proliferants.

Figura 4.1. Cromatograma (HPLC) corresponent a l’oli obtingut de

l’extracció amb cloroform de la pasta. En el cromatograma s’observen els tres productes de la biotransformació (DHOD, MHOD i HOOD) així com també restes de la font de carboni inicial, l’àcid oleic.

D H O D

M H O D

À . O L E IC

H O O D D H O D

M H O D

À . O L E IC

H O O D

10 15 5

0 20

i. Cultius discontinus

Prenen com a referència les dades obtingudes en els cultius de P. aeruginosa 42A2 emprant àcid oleic com a substrat, s’han assajat diferents concentracions de “l’extracte monodi”: 10 g/L i 20 g/L.

Així doncs, es fa créixer el microorganisme en medi mínim mineral, MM1, en agitació constant a 120 rpm i 30 ºC. Aquest medi de cultiu conté una concentració inicial de nitrogen molt baixa, [N]=0,58 g/L. Per tant, es d’esperar que el creixement estigui limitat per la font de nitrogen, però d’altra banda l’acumulació de PHA es veurà afavorida.

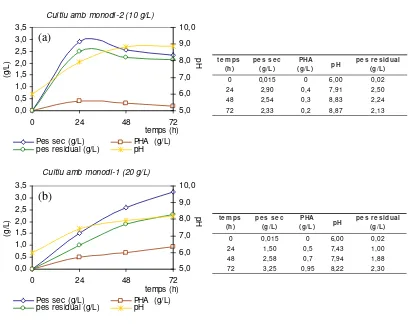

En la Figura 4.2 es detallen les cinètiques obtingudes per a les dues concentracions assajades:

[image:39.595.88.498.346.670.2]En els cultius amb 10 g/L de font de carboni s’observa un creixement molt ràpid i

Figura 4.2. Cinètiques de creixement i producció de PHA dels cultius de P. aeruginosa 42A2 emprant

l’extracte monodi com a font de carboni: (a) 10 g/L i (b) 20 g/L.

0 0,015 0 6,00 0,02

24 2,90 0,4 7,91 2,50

48 2,54 0,3 8,83 2,24

72 2,33 0,2 8,87 2,13

pe s re s idual (g/L) te m ps

(h)

pe s s e c (g/L)

PHA

(g/L) pH

Cultiu amb monodi-2 (10 g/L)

0,0 0,5 1,0 1,5 2,0 2,5 3,0 3,5

0 24 48 72

temps (h)

(g

/L

)

5,0 6,0 7,0 8,0 9,0 10,0

pH

Pes sec (g/L) PHA (g/L) pes residual (g/L) pH

0 0,015 0 6,00 0,02

24 1,50 0,5 7,43 1,00

48 2,58 0,7 7,94 1,88

72 3,25 0,95 8,22 2,30

pe s re s idual (g/L) te m ps

(h)

pe s s e c (g/L)

PHA

(g/L) pH

Cultiu amb monodi-1 (20 g/L)

0,0 0,5 1,0 1,5 2,0 2,5 3,0 3,5

0 24 48 72

temps (h)

(g

/L

)

5,0 6,0 7,0 8,0 9,0 10,0

pH

Pes sec (g/L) PHA (g/L) pes residual (g/L) pH

(a)

obtenint-se els valors més alts tant per la biomassa total com per a la producció de PHA: 2,90 g/L i 0,4 g/L, respectivament. A partir de les 24 h de cultiu, el pes sec decreix fins a 2,33 g/L possiblement com a conseqüència de la biodegradació del polímer acumulat. Tal i com s’ha comentat anteriorment a les 24 h de cultiu, la producció de PHA és de 0,4 g/L, que representa un 14 % (p/p), mentre que a les 72 h de cultiu la producció de PHA és de 0,2 g/L (8 %( p/p)). Al llarg de les primeres 24 h de cultiu, el creixement ha estat molt ràpid i s’ha esgotat tota la font de nitrogen del medi, subministrada en forma de nitrats, i per tant el microorganisme no pot continuar creixent. Conjuntament amb la limitació de nitrogen, el consum del PHA acumulat indica una possible limitació de font de carboni, de tal manera que el bacteri aprofita el poder reductor del PHA i el degrada per tal d’obtenir l’energia de manteniment necessària.

En el cultiu amb 20 g/L de substrat s’observa un creixement més lent. A les 24 h de cultiu el pes sec és de 1,5 g/L i la producció de PHA és de 0,5 g/L. La producció de PHA representa un 33 % (p/p) d’acumulació. Si comparem aquests valors amb els obtinguts en el cultiu de 10 g/L, s’observa que malgrat que la producció de la biomassa pels cultius de 20 g/L és la meitat que la que s’obté en el cultiu de 10 g/L, el procés d’acumulació és millor en aquest segon cas, la producció de polímer es multiplica per un factor de 2,5. El fet que s’observi un creixement més lent podria indicar algun tipus de toxicitat o inhibició relacionada amb la concentració inicial de substrat. Els màxims de biomassa i de PHA s’observen a les 72 h de cultiu, on s’obté 3,25 g/L i 0,95 g/L, respectivament, i que representa una acumulació de PHA del 29 % (p/p). D’altra banda si es considera el pes residual a les 72 h de cultiu per ambdós cultius, amb 10 i 20 g/L de substrat, s’obtenen valors molt similars independentment de la concentració inicial de substrat, 2,13 i 2,30 g/L respectivament. De la mateixa manera si es calcula el rendiment cel·lular respecte la font de nitrogen (YX/N , on x és la biomassa residual (g/L) i N la concentració de font de

nitrogen), trobem que per el cultiu de 10g/L, el YX/N= 3,7 i que en el cas del cultiu amb

20 g/L el YX/N= 3,9. Així doncs, el fet que els rendiments cel·lulars obtinguts en ambdós

casos sigui pràcticament iguals, sembla indicar que creixement està limitat per la concentració inicial de nitrogen.

Està descrit que la relació C/N té un efecte directe sobre la formació de PHA, tot i que el creixement cel·lular es veu afectat negativament. Per tant, es pot considerar que la limitació de nitrogen és un paràmetre important per a la inducció de la síntesi de polímer. D’acord amb Tian et al. (2000) la concentració de nitrogen pot ser emprada com un paràmetre per a controlar el creixement cel·lular i la producció de PHA en el cas de P. mendocina 0806 (Tian et al., 2000).

ii. Cultiu alimentat (10 g/L+10 g/L)

Considerant els resultats obtinguts en cultiu discontinu es decideix canviar l’estratègia de cultiu, per tal de millorar el rendiment del procés. Per això es subministra els 20 g/L de font de carboni en dos polsos de 10 g/L cadascun. D’aquesta manera, el que s’intenta es millorar el rendiment del procés d’acumulació, ja que la relació (C/N) augmenta amb la segona addició, i a la vegada disminuir el possible efecte d’inhibició per substrat que sembla que es descriu a les primeres hores de cultius quan es treballa a concentracions de substrat altes. En la Figura 4.2 s’hi representa la cinètica del procés. Es comença el cultiu amb 10 g/L de substrat i a les 20 h de cultiu s’addiciona els altres 10 g/L de font de carboni i es segueix l’evolució del cultiu al llarg de les següents 72 hores.

[image:41.595.74.517.455.618.2]Tal i com es pot observar a la Figura 3.2, al llarg de les primeres 20 hores de cultius s’arriben a valors de biomassa i de PHA molt semblants als obtinguts en el cultiu de 10 g/L, descrit a l’apartat 4.1.1.1. A partir de la segona addició de substrat, a les 48 h de cultiu, s’observa un augment notable del pes sec com a conseqüència de la millora en el

Figura 4.2. Cultiu de P. aeruginosa 42A2 emprant l’extracte monodi com a font de carboni. Cultiu alimentat

amb dos polsos de 10 g/L a les 0 i 20 hores de cultiu.

0 0,015 0 6,00 0,02

20 2,21 0,30 7,77 1,91

48 2,60 1,04 7,84 1,56

72 3,70 1,61 8,07 2,09

96 4,55 2,04 8,32 2,51

pe s r e s idual (g/L)

te m ps (h) Pe s s e c (g/L) PHA (g/L) pH

Cultiu alimentat amb monodi (10+10 g/L)

0,0 1,0 2,0 3,0 4,0 5,0

0 24 48 72 96

temps (h)

(g

/L

)

5,0 6,0 7,0 8,0 9,0 10,0

pH