THE THEORY OF COMPLEXITY ADAPTED TO INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: THE BEHAVIOUR OF THE VISEGRAD-UKRAINE COMPLEX

ADAPTIVE SYSTEM SINCE NOVEMBER 2013

DANIEL GÓMEZ AMAYA

UNIVERSIDAD COLEGIO MAYOR DE NUESTRA SEÑORA DEL ROSARIO SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

“The theory of complexity adapted to international relations: the behaviour of the Visegrad-Ukraine Complex Adaptive System since November 2013”

Monograph

Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for obtaining the Degree of Internationalist

In the School of International Relations

Universidad Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario

Submitted by: Daniel Gómez Amaya

Directed by:

Carlos Eduardo Maldonado Castañeda Ph.D.

ABSTRACT

Complexity, a theory that is proper to the study of natural-related phenomena, is found to be an alternative framework to understand emergent events within the international system. This monograph correlates the language of complexity with international relations, focusing in the Visegrad-Ukraine relationship, which suffers from unexpected emergent events since the popular uprisings that took place in Kiev in November 2013. The complex system that exists among the Visegrad Group and Ukraine will feel the need to adapt to the recurrent emergent events ever since and self-reorganise in order to behave accordingly to unpredictable scenarios, particularly in regard to their energy-linked interactions and their political interconnections.

Key words: Complexity, Ukraine, Visegrad Group, Complex Adaptive Systems, self-organisation.

RESUMEN

La teoría de la complejidad, propia del estudio de fenómenos relativos a las ciencias naturales, se muestra como un marco alternativo para comprender los eventos emergentes que surgen en el sistema internacional. Esta monografía correlaciona el lenguaje de la complejidad con las relaciones internacionales, enfocándose en la relación Visegrad— Ucrania, ya que ha sido escenario de una serie de eventos emergentes e inesperados desde las protestas civiles de noviembre de 2013 en Kiev. El sistema complejo que existe entre el Grupo Visegrad y Ucrania se ve , desde entonces, en la necesidad de adaptarse ante los recurrentes eventos emergentes y de auto organizarse. De ese modo, podrá comportarse en concordancia con escenarios impredecibles, particularmente en lo relacionado con sus interacciones energéticas y sus interconexiones políticas.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

pp.

INTRODUCTION 11

1. VISEGRAD-UKRAINE RELATIONS THROUGHOUT HISTORY (1991-2014) 14

1.1. 1989-1992: The birth of Central Europe 14

1.2. 1992-2004: Walking different paths leading to the same end 18

1.3. 2004 – 2015: Shifting towards the Central Eastern region 21

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 27

2.1. Complex systems 27

2. 2. Behaviour of a complex system 28

2.3. Emergence and self-organisation 29

2.4. Uncertainty and non-linearity 31

2.5. Adaptability 33

3. THE FIFTH DEBATE: EMERGENCE OF A COMPLEX THEORY OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS 38

3.1. The misconceived linearity of non-linear International Relations 38

3.2. The perils of Causality in International Relations 42

4. THE VISEGRAD-UKRAINE COMPLEX SYSTEM: ADAPTABILITY IN MOTION 46

4.1.The Visegrad-Ukraine Complex System adapts as properties emerge 49

Gas Flow 50

Political Cooperation 54

pp.

REFERENCES

LIST OF FIGURES

ANNEXES

Annex 1. Map. Nord Stream pipeline

ACRONYMS

AA Association Agreement

CAS Complex Adaptive System

CEEI Central Eastern European States

CEI

DCFTA

Central European Initiative

Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area

EU European Union

IR International Relations

LNG Liquefied Natural Gas

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

TASR Tlačová Agentúra Slovenskej Republiky

USSR Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

V3 Visegrad Three

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The unconditional support of my family is absolutely priceless to me. Their patience, their worry, their loving sacrifice and the countless hours of meaningful conversation; I sincerely could not have asked for better shoulders to rely on. I love you all.

To all the professors whose uninterested guidance I cherish. First, and foremost, to Carlos Maldonado to whom I am deeply grateful as well as intellectually indebted. I must admit that understanding the greatness of complexity at first was challenging, even more when having such a self-biased linear perception of the phenomena that surrounds us. Thanks for the guidance, your sincere advice and your warmth. I feel a great deal of respect for you and true admiration for your work. To professor Emilian Kavalski, who was kind enough to recommend some of the sources that have been included in this work aside from providing me with his kind advice. To the initial director of this project Juan Nicolás Garzón. I truly

appreciate your understanding and your continuous interest.

To my friends and colleagues, I can’t tell you how much all your support means to me. To the ones who read these chapters and made the most sincere critiques about them, and to the ones that just asked how it was going, encouraging me to continue writing. I am deeply grateful to you all. Without any shadow of doubt, the greatest support we can receive comes from the ones that are going through the same as ourselves.

INTRODUCTION

What would an international relations (IR) scholar say if told that there is an alternative theoretical framework, which is mostly associated with natural sciences, that defies the linearity of all the IR theories in which they have been relying their researches on? Perhaps this question would baffle most of them considering that a theory that is endemic to natural processes, they may tend to think, would not provide explanations to either political, economical, security-related or any other aspect of international phenomena. Reality is that the theory, or science, of complexity is based on concepts that fit splendidly to the non-linear correlations and interactions that exist within the international system.

Complexity differs from all the IR theories, no matter the paradigm to which they belong, in that it gives reasons for thinking of the international system as one in which unexpected and uncertain events can emerge at any moment, and there is no possible way of predicting the outcomes of any of them. This, in the end, gives the actors the task of self-organizing and adapting to any given situation that emerges from the environment or that appears as consequence of certain shifts in their interactions.

Through complexity one is able to conclude that there are certain interactions that are stronger or tighter than others. However there is no hierarchical differentiation on which set of interconnections is, undeniably, the most important one, unlike the linear theories in which security interests are superimposed to commerce, material capabilities are more important than economical ones or in which domination is the only way to understanding

relationships among ‘core’ and ‘peripheral’ States. Complexity embraces them all, since there is no possible way of explaining an emergent situation within the international system if not approaching to the issue in a holistic way, thus including equally systemic, State-centric and socially constructed factors.

Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, and Ukraine. Since November 2013, when popular upheavals emerged in Kiev as a form of protest against governmental decisions taken by then President Viktor Yanukovich, a chain of convulse events appeared within the complex system that exists among the Group and Ukraine. Whenever a neuralgic matter unleashes from the cloud of uncertainty, be it a popular uprising, a change in presidential office, a threat on gas shortage, the signing of an Association Agreement etc., cohesive actions are to be taken in order to preserve the interactions within the system and, therefore, adapt to the given situation not to lose the interconnection.

It is due to the latter that the effects of the recent events in Ukraine cannot be limited to its repercussion in Ukraine. There is an entire set of dynamics that makes this country merely an agent of one system in which a series of interconnections with the Visegrad States should be preserved, not to mention the interactions with other actors that saunter in the system´s environment, such as Russia and the European Union (EU).

Such being said, this monograph aims at revealing how does Complexity theory, applied to International Relations, explain the behaviour of the Visegrad-Ukraine Complex System1 since November 2013? To which it is argued that in a non-linear relationship, such as the mentioned one, adaptability is the essential attribute that makes a Complex System self-organise in accordance to the emerging events that have appeared unexpectedly in the

System’s environment, affecting the interactions among its components. Such a

relationship is evidenced when approaching to the Visegrad Group and Ukraine’s interactions, particularly to their connections on energy affairs and political cooperation.

In order to demonstrate the applicability of complexity to IR, via the given case, four sets of arguments will be given. Firstly, historical ones; secondly, empirical ones; thirdly, holistic and relational ones; and, lastly, factual ones, related to the state of affairs. Furthermore, after conducting an exhaustive investigation on the topic, nearly no studies

1 Hereinafter, the term written in capital letters refers explicitly to the Visegrad-Ukraine Complex System,

were found in academic data-bases in regard to the existence of a complex system neither among these two actors, nor on the behavioural shift of the Visegrad Group towards

Ukraine and the system’s environment in accordance to the emergent events that will be

outlined throughout the next pages.

1. VISEGRAD-UKRAINE RELATIONS THROUGHOUT HISTORY (1991-2014)

It has now been nearly a quarter Century since both the Visegrad Group was created and Ukraine gained its independence from the Soviet Union. Throughout the past 24 years, relations between the Visegrad Four and Ukraine have not certainly been as close and reciprocal as in the past decade. Even though, interactions have been unstopped and the Visegrad Group has never questioned the existence of Ukraine as an independent Republic, given the common communist yoke that they were all once trying to release themselves from.

Their relationship, then, can be divided into three stages. First, from 1989 which was when the Visegrad States became independent, until 1992, when the V4 rejected the entrance of Ukraine to the Group. Second, from 1992 to 2004, the latter being the year in which the four Visegrad States became full members of the European Union. Finally, since 2004 until 2015, stage through which Ukraine experienced the two greatest crises of its independent history. This was as well the time during which the relations became closer with the V4, due to the support that the group gave to Ukraine a propos the idea of becoming closer to the EU, being the latter, ironically, one of the triggers in a series of still ongoing events that began in the late 2013.

1.1. 1989-1992: The birth of Central Europe

Civil demonstrations of support for non-communist social and political movements

in Bratislava, Prague, Budapest and Warsaw were constant during the 1980’s. The popular

pressure and the political anxiety to establish a new government finally escalated until the point of engaging in democratic elections and choosing non-Soviet members of Parliament and Heads of State. The Polish and Hungarian successful upheavals were sealed, possibly in no better way than with the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 9th 1989, due to the legitimization that such event provided to their abandonment of the Soviet regime and mostly to their new governments. In the aftermath of the Wall incident, the Velvet Revolution led to the independence of Czechoslovakia from the USSR. A couple of weeks later a new decade came into being and, with it, three new Central European States.

The now independent institutions and the new political dynamics were being strengthened and consolidated progressively within these newborn States, however the integration process that involved the security and economic cooperation organizations of Western Europe was hardly showing any progress. For that reason a couple of years later, in 1991, the Republics of Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland decided to engage in a cooperation project of their own.

On February 15th 1991, Václav Havel, Josef Antall and Lech Walesa, the leaders of the newly established States, met in Bratislava and signed the Declaration on cooperation between the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic, the Republic of Poland and the Republic of Hungary in striving for European Integration. Such document constitutes the

establishment of the Visegrad Group. The so called ‘V3’ or ‘Visegrad triangle’ was named

As the wording of the Visegrad Declaration suggests, the Group was created to cope jointly with the intricate political situation that resulted from the atomization of the USSR and ultimately to integrate fully into the West European interactions. Additionally, in said

document the three parties declared their will to “eliminate all existing social, economic

and spiritual aspects of the totalitarian system; construct a parliamentary democracy, a modern State of Law and respect for human rights and freedoms; create a modern free market economy; and involve entirely in the European system of security and legislation” (Visegrad Declaration, 1991, para. 2).

The Visegrad Group was one of the first initiatives of regional cooperation of the Central and Eastern European States. Nevertheless, the Group was not designed to be an alternative to the European Union nor NATO or any other institution that is considered as a forum prone to cooperation with the West. On the contrary, the oath of allegiance made by the V3 is the vehicle these States chose to board in their search for full European acceptance. In 1993 however, Czechoslovakia accorded the division of the country into two separate Republics, the Czech and the Slovak. Such was not an impediment to continue with the process of integrating into the European free market, although it did pose additional challenges to the ulterior success of the project, coming from their new heads of government.

In the meantime, quite a few kilometers to the East, the situation regarding independence was still unsolved. At the time of the creation of the Visegrad Group, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was still resting under the Soviet Union´s left wing. The way in which Ukraine became independent resembles in no way to the revolutionary acts led by civil movements in Czechoslovakia, Hungary or Poland. On the contrary, the Ukrainian secession was much more sudden given that it was triggered by an attempt of

Rada2) on August 24th 1991 ordered that a referendum should be held four months after the independence was proclaimed in order for the citizens to confirm the decision. (Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian SSR, 1991, p. 4 )

The decision taken by the Rada in August was widely supported by the Ukrainians in December. However, even prior to the referendum the Visegrad Triangle had already recognized Ukraine as an independent State. Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, along with Bulgaria and Canada were the first States to recognize internationally the existence of the Republic of Ukraine. (Fawn, 2005, p. 125) From this moment on, the interactions between the V3 and the new Central Eastern European State (CEES) began to self organize in response to the convulse environment in which they were submerged.

Ukraine, such as the rest of the emerging CEES, was in search for mechanisms that could allow the State to establish political and economic connections with the rest of the continent. Nevertheless, there was a particular feature that made different its process of integration from those of the remaining Central and Eastern States, including the V3: its relationship with Russia. Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia had not been Soviet Republics, as Ukraine was. The latter was part of the territory of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics until the very day in which the referendum backed up the Rada’s decision of becoming an independent State, during the last month of 1991. The Visegrad States, on the other hand, were not officially part of the USSR, but they did have communist imposed pro-soviet regimes that lasted for decades.

Ultimately, what mattered at the moment of the joint venture towards the future, were the similarities in the upcoming project of State that they mostly shared. The true importance of Ukraine for the Visegrad States, geopolitically speaking, was, first, the opportunity that the Ukrainian territory represented in terms of energy (hydrocarbon) flow given that the rich Russian pipelines and gas ducts run across its territory, and second, the fact that the Visegrad States could take advantage of Ukraine´s eagerness to get closer to its

Western neighbours in order to have an ally that still held strong ties with Russia. It was a strategy that could serve to maintain Russia neutralised, or in other terms, keeping it close enough as to assure non post-independence retaliations plus energy supply, and far enough to maintain a prudent relation that would not compromise the relations with the rest of the West European States.

In despite of the pledge for European integration that the V4 claimed, and of how appealing it seemed to be for other emerging States of the region to join the Visegrad cooperation initiative, the group was firmly decided not to accept any other member. Ukraine was not even independent at the time of its creation, so technically the Visegrad Group is older than the Ukrainian State itself, even if it is only for a few months. In that sense, for when they had already built two years worth of path out of major efforts, they would think twice, three times or as much as they considered before admitting the addition of a new road builder.

The members of the Visegrad Group knew that it was better having a fragile and somehow Russian biased State as Ukraine on their side. But they also knew that allowing such a country to join the Group as a full member would significantly draw out the process of rapprochement with the EU and NATO members. In 1992 therefore, the Visegrad Group rejected the official membership application submitted by Ukraine. (Wolczuk, 2003, para. 2-3) The Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia, considering even that some of their national interests were slightly dissimilar, knew very well that if they wanted to become a desirable member for the Western institutions they should build their path together, as in a sort of a 4-seat exclusive vehicle riding through a one car speedway lane.

1.2. 1992-2004: Walking different paths leading to the same end

they decided to gradually forge their way on their own, instead of depending on the Group to reach their goal, although it must be said that the integrity of the regional body was never seriously compromised.

Polish President Lech Walesa, on the one hand, started promoting the idea of a

‘NATO-Bis’ in 1992. The project envisioned by the leader of Poland included not only the remaining two Visegrad members but also Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. Walesa thought

that this ‘club’ served, first as an alternative to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization as the members of the alliance were not showing any particular interest on dealing with these countries, and then as a forum that would prepare their parties for when NATO eventually consented their membership. (Hyde-Price, 1996, p. 239)

As the former idea never came into existence, Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk in a failed attempt of leading a prosperous project of regional integration, proposed the

creation of a ‘Zone of Stability and Security’ in 1993, from the Baltic to the Black Sea.

The Ukrainian bid included the same States as its Polish counterpart’s, plus the three Baltic

States and a couple other Central European actors such as Romania, Bulgaria and even Austria. However, it excluded Russia. The sole idea of having such a large security area without including Russia was challenging, especially for the Visegrad Group since it was being already threatening to pursue NATO membership so shortly after they had cut all political ties to Russia now for them to allegedly exclude a key country that they could not afford to have as a declared enemy. (Wolczuk, 2003, p. 99)

Ukraine, in despite of the failure of the two mentioned projects and of Visegrad’s

membership rejection, was somehow being taken into account when thinking of regional

integration. “Kyiv sought to join CEFTA and some of the working groups of the Central European Initiative (CEI). Polish and Hungarian representatives supported Ukraine’s

application for CEI membership, which was approved on May 31st ,1996 . The Visegrad

countries also helped Ukraine enter the Council of Europe in November 1995” (Wolchik &

The, so far, close relations among the Visegrad States, nevertheless, were beginning to grow fainter. According to Martin Dangerfield, Professor of European Integration and Jean Monnet, Chair in the European Integration of Central and East Europe (2009) “the period 1993-98 is usually characterised as, at best, a time of dormant VG [Visegrad] cooperation” (p. 4). After the 1993 Czechoslovak split, the newly appointed Prime Ministers of the Czech Republic and Slovakia became actors that somehow posed

additional challenges for the Group. Vaclav Klaus and Vladimír Mečiar, respectively, were

not neither entirely pro Western nor Visegrad cooperation enthusiasts:

The Czechs thought that regional co-operation was a subtitle for the ‘real’ goal of ‘going West’. Slovakia, the only country with borders with each of the other three, could hardly reconcile the Visegrad Group co-operation with its difficult relations with Prague and Budapest. All this changed since 1998 with the departure from office of Mečiar and Klaus, and, the ensuing convergent Czech and Slovak policies towards Visegrad and EU/NATO enlargement. (Rupnik, 2003, p. 41)

Furhtermore, during the 1997 NATO Madrid Summit, the Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary were invited to join the alliance. The three Visegrad States finally became members of said organization on March 1998, though the Slovak Republic was excluded of the enlargement process. (Cottey, 2000, p. 36) These countries became the first ex communist allies and opened the door for other non western States to become part of

NATO. Ukraine, however, was not in the alliance’s list for potential application. As a

swing State, it was perilous for NATO to face Russia in such a decisive way as it was for Ukraine first, to attempt becoming a member of an organization that was historically against its giant neighbour and second, to put at risk the relations with Russia, given the still dependent ties they preserved.

Notwithstanding the North Atlantic allies were not expetcing Ukraine to be a member of their organization in a near future, they acknowledged the importance, just as the Visegrad Group did and still does, of having Ukraine close to their interests. For that reason, NATO and its Eastern counterpart signed the Charter on a Distinctive Partnership

directly on said issue, they did open the door for further NATO enlargement or partnership for the remaining former communist Republics of Central and Eastern Europe, which Ukraine clearly took advantage of by signing the Distinctive Partnership agreement in 1997 and reinforcing it in 2009.

During the following years, the Visegrad countries focused on commiting to the conditions that the European Union imposed to them in order to continue with their membership candidacy. The Hungarian Presidency of the Group between 2001 and 2002, aside from keep on pursuing EU integration, had the enhancement of the V4 relations with Ukraine as an important subject. The Group even invited commissioners from the EU to attend a meeting in November 2001, in which delegates from the Visegrad members and Ukraine were meant to discuss several methods to strengthen Ukraine’s development and closeness to the regional integration initiative. (Hungarian Presidency of the Visegrad Group , 2001) A couple of years later, the four Visegrad States were at last ad portas of accomplishing one of its main goals, which also happened to set a turningpoint regarding

the Group’s relationship with its key Eastern Partner.

1.3. 2004 – 2015: Shifting towards the Central Eastern region

One of the main if not the primordial objective, that moved the Visegrad States to engage in regional cooperation, by means of the Visegrad Group, was fulfilled in 2004. The Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia were admitted as full members of the European Union on the first day of May 2004. With thus being achieved after thirteen years of lobbying, internal institutional adaptation and an arduous stage involving conflicts of interests among the four members, the V4 managed to engage in the dynamic cooperation of the region not as an alien partner but as a member party.

Takacs, 2013, p.7) Said document set a new route that gave a whole different meaning to the raison d’étre of the Group. The Declaration states that the Visegrad States:

[…]Reiterate their commitment to the enlargement process of the European Union. They are ready to assist countries aspiring for EU membership by sharing and transmitting their knowledge and experience. The Visegrad Group countries are also ready to use their unique regional and historical experience and to contribute to shaping and implementing the European Union's policies towards the countries of Eastern and Southeastern Europe.

The Visegrad Group countries are committed to closely cooperating with their nearest partners in the Central European region. (The Kroměříž Declaration, 2004, para. 4-5)

That very last sentence is the one that sets the inclusion of Ukraine in a much more significant level. Ukraine borders three of the four Visegrad States, namely Poland, Hungary and Slovakia, therefore since the EU enlargement of 2004, the Visegrad Group became the natural border of the European Union to the East. Since then, Ukraine became much more prone than ever to be a potential candidate for EU partnership, being sponsored by the new Central European members or why not, they thought, for future membership.

Membership, due to various factors such as institutional weakness, being a pivot to Russia, and the basic question of it truly belonging ethnically, culturally or politically to

Europe or not, makes it hard for the EU members to step up Ukraine’s status to more than a remote candidate. The mentioned matters raise countless doubts that restrain the consideration of Ukraine for European membership.

The Visegrad Group, conscious of that particular situation, began lobbying in order for Ukraine to acquire certain perks and seek a formal Partnership Agreement. The State that led the Ukraine lobby, with the support and consent of the remaining three members was Poland, given that it was the country that had the closest relations with Kiev, and still does, out of the Visegrad Group. (Kaminska, 2014, p. 82)

promptly as their proponents expected, mainly because it was proposed very shortly after Poland and the other Visegrad States joined the EU, meaning that they were still learning the formal procedures, accommodating to the institutional norms and familiarizing with Visa procedures within the organization, and also, because it was not backed up by many EU members. (p.82) Even the Czech Republic and Slovakia were still reluctant to the idea of having Ukrainians to enter their territories Visa-lessly.

Changing radically the scenario, the Orange Revolution that took place in Ukraine between 2004 and early 2005, happened to turn out well for the country in terms of regional support as well as of future opportunities for broader EU advantages. The change in government was the shift that Ukraine needed regarding European integration, given that Viktor Yanukovich was more on the pro Russian side than the candidate that was finally elected as President, Viktor Yushchenko. (Sushko, 2004, pp. 2-3)

From this particular event, during which Ukraine suffered from a two-month power vacuum, was that the Visegrad Group as a whole began to bid resolutely in favour of its EU rapproachment. Prior to the revolution, however, Yushchenko’s approval of engaging in much tighter interactions with NATO and the European Union, made Slovakia and the Czech Republic to reconsider their Visa related restrictions for Ukrainian citizens, and to support the lobbying of their two other Visegrad partners in a way that was ostensibly more sincere. (Zielys, 2009, p. 41)

2004, however, was not only the year in which the Orange Revolution took place. This was also the year during which the 1994-2004 Partnership Cooperation Agreement

(PCA) between the EU and Ukraine expired. As the elections in Ukraine had finally favoured Yushchenko, the members of the Union may have decided that the timing was good enough for them to offer an Association Agreement (AA) to its Eastern neighbour.

was in favour of the parties, and Poland, along with its three other Visegrad colleagues, was supportive of the idea, the preparation towards negotiations for the AA began earlier. What has to be taken into account is that the PCA automatically renewed itself or had to be enforced continuously until a new agreement was signed and ratified by the actors involved, and also that the formal process of negotiation aimed at subscribing the AA only began after the 2008 Paris Summit. (Tyshchenko, 2011, pp. 10-11)

The negotiations culminated succesfully in 2012 and even included, within the framework of the AA, an opportunity for Ukraine to get involved, to a great extent, in the European market, via the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA). (Tyshchenko, 2011, p. 11) Ever since, the Association Agreement3 has been ready to be signed and ratified by both Ukraine and the 28 members of the European Union.

In the meantime, and as a parallel measure of cooperation with their Eastern Partners, the V4 came up with a project that had been designed with the purpose of enhancing the relations as well as the bilateral political and technical cooperation of the

Group with certain States. The Visegrad Plus or ‘V4+’ initiative was formalized during the period of the Group’s Hungarian Presidency of 2010.

The objective of this cooperation strategy, according to what the four Heads of

Government affirmed during their 2010 Budapest Summit is “promoting […] the Euro-Atlantic integration of the Western Balkans and the Euro-Euro-Atlantic alignment of the Eastern Partners, strengthening energy security of our region, [and the] adoption of a common

spatial development document […]” (Heads of Government of the Visegrad Group, 2010,

para. 2) The Visegrad Group, as a result, became a sort of paliative for other Central European countries. States such as Moldova, Serbia, Croatia and Ukraine that had not been included in the EU enlargement processes of 2004 and 2007, kept themselves marginalized of many perks that are proper to members of the Union. Therefore, the Visegrad Group, via the ‘V4+’ and the, must be said, precarious Visegrad Fund, tried to be the leading head of Central and Eastern European integration. This cooperation platform surely encompasses Ukraine, and it has been particularly useful when dealing and expressing their support during the 2014 crisis.

The crisis that began in Kiev in 2013 with a popular upheaval that was triggered,

among several reasons, by President Yanukovich’s refusal to ratify the Association

Agreement with the European Union, rapidly escalated into a regional crisis which

involved not only Ukraine’s western neighbours, but Russia as well. “The main risks would

include the interruption of energy supplies, possible instability in the border regions, and the influx of migrants on refugees. These common interests strongly motivated the

Visegrad Group to take joint actions during the crisis” (Rácz, 2014, p. 4).

For instance, during a meeting in Kiev of V4 leaders and Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko shortly after he assumed office, the Slovak Deputy Prime Minister Miroslav

Lajčák, on behalf of his country and of the other three Visegrad members, declared:

Slovakia will be the leading country in the areas of Energy Security and Security sector reform; Poland will be a leading country in the areas of decentralization, reform of regional and local administration and management of public finances; Czech Republic will be a leading Nation in the areas of civil society, media and education; and finally, Hungary will be the leading country for economic policy, support for the small and medium-sized enterprises and the implementation of the CEFTA. (Lajcak, 2014, 1:16-1:43)

with the very Ukraine, have managed to cope with such an unpredictable phenomenon. The latter will constitute the objective of this research; therefore it will be thoroughly discussed in subsequent chapters.

Professor Andrei P. Tsygankov Ph.D synthesizes the Ukrainian political struggle in

its international front by affirming that “for Ukraine, a culturally torn country, the challenge

is to preserve a balance in its foreign policy vis-à-vis Russia/CIS, on the one hand, and the

West, on the other” (Tsygankov, 2001, p. 206). This premise, ultimately, could be applied

2. THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

First and furthermost, the components of the theory of complexity were not dearly intended to fit the dynamics of the international system. Complexity was meant to relate to biological, chemical, mathematical and evolutionary phenomena, among other natural scientific disciplines, which could serve from most concepts developed by the theory in order to explain neuronal functions, numeric equations, the reactions and bonds of chemical elements and the evolution of organisms via, mostly, computational modeling. Nevertheless, certain recent investigations led by complexologists, such as Emilian Kavalski and scholars of the field of International Relations, such as Robert Jervis, just to name a couple, have found an ontological closeness among Complexity and International Relations.

Somehow, there are several elements of chaos and complexity that may be inserted accurately into the analysis of State interactions and the way in which they behave, be it through patterns, impulses etc. The International System, by itself, has been considered by some as a complex system. In a minor level, the interactions that are built between two or more actors within the international scenario, constantly involve violence, poverty, commercial exchanges and many other elements that are covered by clouds of uncertainty, unpredictability and non-linear dynamics.

2.1. Complex systems

In the case of the V4-Ukraine complex system, their multiple and equally relevant interactions, which go from energy cooperation to political cooperation, just to name a

couple, are so interconnected that any variation or disruption in the system’s dynamics will, by and large, have consequences in all of its agents. In such sense, Jeffrey Johnson (2013) asserts that the science of complex systems “attempts to provide methods of understanding

the dynamics of systems where conventional methods fail. […] There are many systems in which the behaviour of the whole emerges from interactions between the parts, e.g. traders in markets, birds in flocks, people in cities, and cells in bodies” (p. 8) to which now States in the international system must be added. The nature of the system makes it virtually inevitable of decomposition.

The key aspect then is not taking every single agent that form the complex system as a micro-structure since, by definition, the sense of system falls apart. The feature that must be considered is the self-organisation that occurs from the actions that the agents take in regard to one another, forming thus the out coming behaviour of the entire system. What truly matters when approaching to a complex system are the interactions that result from the unpredictable behaviour of the agents which are conditioned by an uncertain and non-linear environment.

2.2. Behaviour of a complex system

However, this does not mean that the behavior of each Visegrad State would be thoroughly evaluated in a unitary level, although approximating to their individual behaviour is helpful to understand the adaptation of the Group to emergent events. Yes, each of their actions in regard to the variables must be taken into consideration. Yet, to what this investigation concerns, the V4 will, mostly, be taken as a whole, meaning that the behaviours that will be analyzed, in a particular level, will be: the Group’s, on one hand,

and Ukraine’s, in the other. Then, after fulfilling each description of the parts, is when both

sets of actions and behaviours are interrelated to determine which are the core interactions of the two agents and how the complex system self-organises, which is strictly what matters in this context, just as Bar-Yam suggests.

2.3 Emergence and self-organisation

There are two intrinsic conceptual aspects to complex systems. This duo gives the actual basis of what a complex system is since it condenses the nature of unpredictability and non-linearity: emergence and self-organisation.

On the one hand, “systems may develop emergent properties that do not derive from

a simple aggregation of their components, and it is the interaction among the system's components that creates the complexity and uncertainty that characterize the resulting

system” (Hoppmann, 1998, p. 314). The emergence, then, is the channel through which any variation in the dynamics of the complex system is transformed into new properties, coming either from the environment or from the interactions among its components. Such properties or events that emerge unexpectedly are the ones that reconfigure the interactions, due to the molding of the previously existing conditions.

Furthermore, “when a system has a global emergent property, the behavior of the

States separately, not only with their Ukrainian counterpart, but also with other actors in the Complex System’s environment.

Bar-Yam’s assertion ratifies the idea of the interactions among agents being the key to understanding the behaviour of the complex system, and the unpredictable outcomes that are product from such interactions. Resulting from the latter, the components of the complex system may begin to design a set of patterns, and new interactions that respond to no external authority, just to the dynamics that must be coped with as a comeback to the alteration provoked by the unforeseeable occurrence. As Neil E. Harrison (2006) puts it, "Properties of the system are emergent, created by the interaction of the units" (p. 5). It is due to those stimuli or events that the environment by which the complex system is surrounded gains its relevance.

The International System, being itself an open and anarchic field in which uncertainty, non-linearity and unpredictability set their flags, serves as the environment in which the V4-Ukraine Complex System sets. “We see that emergent properties cannot be studied by physically taking a system apart and looking at the parts (reductionism). They can, however, be studied by looking at each of the parts in the context of the system as a

whole. This is the nature of emergence […]” (Bar-Yam, 1997, p. 11). The events that have taken place within the Visegrad-Ukraine Complex System are, therefore, an example of the way in which the emergence of new properties in the core of a given complex system leads to the adaptation of the bonds among its components.

Regarding now self-organisation, the concept implies that there are no guidelines for the components of the complex system to create new interactions. The properties that emerge are spontaneous and respond to a certain event, be it fortuitous or not.

However, the way in which interactions are reset do not follow any authoritarian imposition nor any order coming from a hierarchical superior. The components of the complex system interact and organize on their own in response to emergent properties, hence the term self-organisation. Then, if emergence is linked to the interactions that are created within the complex system, self-organization is proportionally linked to the structure of the system itself. The latter, then, can be seen as the organisational response of the complex system to the perks of emergence.

2.4Uncertainty and non-linearity

Sufficiently has it been reiterated the role that uncertainty and non-linearity take when it comes to explaining complex systems. But, what exactly do complexologists mean as they

refer to them? On the first place, in L. Douglas Kiel’s and Euel Elliott’s (2004) concept

“uncertainty is an important element of nonlinear systems since the outcome of changing variable interaction cannot be known” (p. 6). This term is strictly related to behaviour. The fluctuant nature of the interactions that exist within any complex system makes it impossible to know exactly which will the outcome of a given event or stimulus be. In this sense obviousness ans expectedness, which are both impossible amid a complex system, are the antithesis of uncertainty.

What Stuart Kauffman (1995) has to say about this is fairly on the same page of what has already been stated. However, Kauffman mentions not only uncertainty, when referring to the outcome of the actions taken place amid complex systems, he introduces unpredictability.

Then, not only is one unable to know precisely which will the repercussion of any act be, but due to such, one would not be able to accurately predict the result of a given event nor the behaviour of the players affected.

Moreover, nonlinearity doesn’t concern merely the behaviour of the components of the complex system. This concept refers to the product of such behaviour, namely, the possible and multiple outcomes to one single event, impulse or problem. In order to reach a better understanding of nonlinearity, the work of mathematician Henri Poincaré must be brought up since his findings constitute the milestone of the concept. Poincaré did not spoke exactly about nonlinearity. What he did was to determine that the initial conditions of an event or phenomenon should be known in order to attempt knowing the possible paths it may follow towards an outcome or solution. (Tufillaro, Abbott, & Reilly, 2013, pp. 2-3)

Regarding the findings of Poincaré and the mentioned behavioural nature of the agents, Tufillaro, Abbott and Reilly (2013) provide two cases through which they exemplify the nature of the concept: “Some of the motions around us - such as the swinging of a clock pendulum - are regular and easily explained, while others - such as the shifting patterns of a waterfall - are irregular and initially appear to defy any rule” (p. 1). Both of the examples that these authors offer are ideal to elucidate the dynamics of linear and nonlinear systems. On one hand, the pendulum of a clock swings invariably for as long as the mechanical system remains in motion. The movement of such pendulum is predictable, as it resembles the precission that is proper to a clock’s linear system. The linearity relies on the certainty that there is a force that pushes and pulls the pendulum, responding to the synchronization of the system, and that will perpetually cause the very same outcome.

conditions and the interactions of such input with the environtment. That is what makes a waterfall a nonlinear system.

The same happens with the interactions among Ukraine and the V4. There is, for example, political cooperation from the Visegrad States towards Ukraine amid the frame of the European Union. Such cooperation guide the complex system to behave in friendly and condescending terms, at least to what such realm respects. However, the interactions of the agents of the complex structure led to the emergence of civil riots in Kiev in November 2013, which then turned into a bigger concern when other actors became involved. These are unforeseen events that were the outcome of a set of political interactions that were not meant to provoke them, whatsoever. The latter is just an example of how emergence and nonlinearity are both concepts that are helpful to illustrate the situation.

2.5 Adaptability

After all that has been said, the V4-Ukraine complex system that has been depicted can be classified as, what John Holland calls, a complex adaptive system (CAS). In Holland´s own

terms: “A CAS [Complex Adaptive System] consists of a large number of interacting individuals, called agents, that adapt or learn as they interact” (Holland, 2007, para. 6). Certainly, as it has been stated, the complex system conformed by the V4 and Ukraine has proven to be adaptive to the circumstances that arise as unexpected events emerge. Far from falling apart, the behavior, not only of each agent, but of the entire system has shifted in response to the crisis. This creates emergent properties that will be the ones that make the whole complex system to respond assertively to the events that cannot be foreshadowed.

On this same realm Murray Gell-Mann, the Nobel-winning physicist who first

introduced the term ‘Complex Adaptive System’, gives four characteristics for identifying a

The following are general characteristics of a CAS:

1. Its experience can be thought of as a set of data, usually input output data, with the inputs often including system behavior and the outputs often including effects on the system. 2. The system identifies perceived regularities of certain kinds in this experience, even though

sometimes regularities of those kinds are overlooked or random features misidentified as regularities. The remaining information is treated as random, and much of it often is.

3. Experience is not merely recorded in a lookup table; instead, the perceived regularities are compressed into a schema. Mutation processes of various sorts give rise to rival schemata. Each schema provides, in its own way, some combination of description, and (where behavior is concerned) prescriptions for action. Those may be provided even in cases that have not been encountered before, and then not only by interpolation and extrapolation, but often by much more sophisticated extensions of experience.

4. The results obtained by a schema in the real world then feed back to affect its standing with respect to the other schemata with which it is in competition. (Gell-Mann, 1994. pp. 18-19)

What seemed to be an agent-based Complex System among Ukraine and the Visegrad Group turned out to be an Adaptive one, after considering these principles. The inputs, in the case of the V4-Ukraine Complex Adaptive System are, at first, the political negotiations in which the Visegrad countries intervened to include Ukraine in the European Eastern Partnership program. However, it was precisely Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovich’s rejection to sign the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement the first unexpected emergent property, along with the civil protests in Kiev that then escalated nationally, to which the Complex System had to adapt. This input, which comes from the political behavior of the agents involved in the CAS, produced a series of disproportionate outputs that had effects in the entire system as not only the political interactions were affected but the commercial, energy-linked and migratory, among others.

What this demonstrates is precisely that whenever a neuralgic matter unleashes from the cloud of uncertainty, cohesive actions are to be taken in order to preserve the interactions within the system and, therefore, adapt to the given situation not to lose the interconnection. It is due to the latter that the effects of the recent events in Ukraine cannot be limited to its repercussion in Ukraine. There is an entire set of dynamics that makes Ukraine merely an agent of one system in which they all invariably relate to one another. Ultimately, the properties that emerged in the CAS’ environment since 2013 did not affect the Visegrad Group on its own, as it did not affect Ukraine by itself; they disrupted sets of interactions that existed among the two of them. This being said, Reuben Ablowitz succeeds in explaining what has just been exposed by means of a tuneful analogy:

If I play two notes together on the piano, there is an aspect of quality of this sound which is not the property of either of the notes taken separately. The chord has the characteristic of ‘chordiness’; the harmonious combination of sounds has a new attribute which no one of its individual components had, but which is due solely to their togetherness. (Ablowitz, 1939, p. 2)

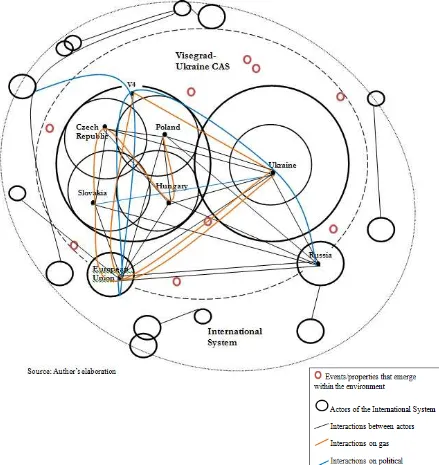

Figure 1. Structure of the Visegrad-Ukraine Complex Adaptive System.

ones, but still in a harmonious way. The viola, as it is still the other component of the duo, has to be refurnished and adapted to the new sounds of the violin, even when it remained apparently unaffected by the environment or the string overstretching.

When other instruments in the orchestra, which resembles the existing actors in the environment of the CAS, such as Russia and the EU, are to play a march together, they receive the impact of the strings that were stretched out since the sound made by the duo will be unexpected. The orchestra would have to continue playing, in a different way, but it will still be playing. As of the violin and viola, they will still be able to play a wondrous symphony when adapted to the sounds of each other, but the noise of the other instruments would be absolutely out of key.

3.THE FIFTH DEBATE: EMERGENCE OF A COMPLEX THEORY OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

Non-linear systems are able to be found practically everywhere, though not every existing system is non-linear. Just as in the example of the clock’s pendulum given in the previous chapter, many other daily perceivable activities are strictly linear, such as the way in which an engine ignites in order to produce vehicle motion or the way in which the audio system, in said vehicle, reads a CD.

In that same sense, several actions that take place within the International System are prone to be taken in a linear fashion, given that certain type of outcomes regarding phenomena such as war, trade, migration can respond to similar historical or current factors. In fact, most of the paradigms in International Relations that are considered as traditional, and to a broader extent, even those that are not properly the classical ones, usually analyze international phenomena through a linear perspective. Given that the previous chapter presented the origins of the Sciences of Complexity and its ambiguous application in natural sciences, in this chapter Complexity turns into a tool that not only fits biology or mathematics but an actual social science, such as International Relations.

3.1 The misconceived linearity of non-linear International Relations

International Relations should be thought of not just by merely relating the actors to one another, or finding the ways in which they interact, but instead, or let’s say, as well, knowing that actors not only interact within the system, they also interact with the system itself. None of those approaches are exclusory form one another. That is why categorizing

The so-called debates, that have taken place among the multiple theoretical streams of the discipline of International Relations, have all ended up by presenting scientific or epistemological arguments rather than integrating the different perceptions of each theory in order to have a broader awareness of the perceived reality. In this respect, Thomas Kuhn (1996) could not be more accurate when presenting the close-mindedness that becomes evident by the way in which normal scientists conceive their surroundings. Normal scientists engage in

An attempt to force nature into the performed and relatively inflexible box that the paradigm supplies. […] those that will not fit the box are often not seen at all. Nor do scientists normally aim to invent new theories, and they are often intolerant of those invented by others. (p. 24)

Kuhn made, back in 1962, one of the most outstanding contributions to the methodological differentiation of the way in which the phenomena of multiple disciplines are studied. More than half a century has gone by, and still the nature of what he called

‘Normal sciences’ is invariable. The discipline of International Relations has not been exempt of the permeation of Normality. Furthermore, the discipline itself is often simplified by categorizing it into a normal science, given its realist grounds and the subsequent theories that have sprouted from Realism and against it. Complexity did not quite enter the theoretical discussions in International Relations until Jack Snyder and Robert Jervis published their work Coping with complexity in the international system in 1993.

The latter was the first approach of Complexity as a holistic alternative to the traditional and normal [in Kuhn´s normal scientific terms] paradigms of the discipline. In 1975, John G. Ruggie had dedicated a chapter on Todd La Porte’s Organized Social Complexity: Challenge to Politics and Policy (Ruggie, 1975) to present shortly how Complexity could be useful when planning public expenditure. Ruggie’s dissertation used

the term ‘planning’ in a Complex context. Perhaps, he was trying to propose a sort of

instead of presenting several concrete scenarios based on the multiple possible outcomes that would derive from a certain strategies of public planning.

In 1977 Robert O. Keohane and Joseph Nye Jr. coined a revolutionary term, considering the ingrained realist perception that a State should be self-sufficient and, thus, should be able to guarantee its own military security and, at a much lower extent, its economic stability without depending on any exogenous transaction. Complex Interdependence, though it gave a different view of the interactions among the actors of the International System, was almost exclusively focused on economic interdependence and commercial bargaining, leaving aside the countless other axes that are also interdependent between States, Institutions and the remaining actors of the system.

Additionally, in the first revision of their text, that was published on the tenth anniversary of the original Power and Interdependence, the authors claim that the realist hierarchical organization that sets military power over economics is to fade with the emergence of Complex Interdependence (Keohane & Nye, 1987, p. 730-731), just as one would expect to happen if grounded on a Complex non-linear perspective. However, a few paragraphs later, Keohane and Nye remind the reader that “In chapter 1 [pgs. 16-17 of the 1977 publication] we argued that it must always be kept in mind furthermore that military

power dominates economic power… yet exercising more dominant forms of power brings

higher costs. (1987, p. 731) Such an assertion vanished the promise of a truly Complex theory of International Relations, even if it was meant to be framed by the neoliberal stream of the discipline.

The previously mentioned attempts of inserting Complexity into the International

(Neo)Structuralist is one in which nonlinear dynamics, self-organization, resilience and the distancing from simplistic assertions are presented as some of the main contributions to the study of the complex international life.

The rise of a Complex International Relations theory suggests the need for the phenomena of the discipline to escape from the linear cell that all the previous paradigms had locked them in. The insertion of Complexity in the study of world affairs does not, as Kavalski reminds that Gerry Gingrich (1998, p. 1) states, “ ‘yield answers, at least not in the sense of those we have typically sought to describe our world and predict its events since the beginning of the Scientific Revolution. What it does yield is a new way of

thinking about the world’ ” (Kavalski, 2007, p. 438).

To a larger extent, Emilian Kavalski notes that the theorists that find in Complexity the ultimate way of approaching to world affairs describe the International System as a Complex Adaptive System. In the author’s own words the Complex Adaptive System

perspective suggest that: “(i) it is not a cluster of unrelated activities but an interconnected

system; (ii) that this is not a simple system, but a complex one; (iii) the interconnectedness between the parts of the system is not unchanging, but constantly self-organizing—that is,

it is their capacity to cope with new challenges that makes the system adaptive” (2007, p. 444). He relies on the explanations given by Lars-Erik Cederman, James Rosenau and Louise Comfort, three of the scholars that are known for integrating concepts of Complexity with International Relations, to emphasize in the resilience and relative order that self-organization and emergence provide to the system.

Besides considering the International System as a Complex Adaptive one, the Fifth Debate also adds an ontological novelty to the non-linear approximations to the discipline.

Stemming from Gunderson and Holling’s theorizing, the term panarchy emerges as a

In order to understand thoroughly what panarchy is an example based on the author’s findings will be provided.

Imagine the human food chain. For a human to eat, it must interact with the environment: an individual hunts, harvests crops, fishes, trains other animals to help them find potential nourishing sources, among others. However, the food chain is susceptible of being altered by the environment. Unexpected natural phenomena such as droughts, floods, blizzards or demographic variations can affect the production. Similarly, man provoked events like oil spills, mismanagement of natural resources, overexploitation and market failures can also affect the production and distribution of food . So, how to cope with these emerging properties? How to create a balance so that dealing with one problem would not provoke two additional problems derived from the first one? Those are the real challenges.

Humans not only interact with the ecosystem, they also interact with their political

environment and with one another’s thoughts. The actors in the International System do the

same; they interact with each other and with the system itself, coping with emergent properties that sometimes are provoked by themselves or that may emerge from structural responses to unpredictable events. States, institutions and the other multiple actors in the international complex system also have to cope with change and persistance and with the predictable and unpredictable, even though relying on the predictable may cause the actors to ultimately rely on nothing, since predicting the exact outcome of an impulse is far from being plausible.

3.2 The perils of Causality in International Relations

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo, in 1914, has been claimed by many as the reason that led to one of the deadliest conflicts in recent history.

What about the Imperial downfall? Or what about the nationalistic sentiments that were sprouting throughout Europe at the time? And what is to be said about the prestige that each of the involved territories would gain via the appropriation of new lands and resources? The Great War was not the consequence of a single stimulus. A bare murder could not have caused millions of casualties and the reorganization of an entire continent, including the dissolution of some of greatest empires in the West.

There is no such thing as causality when considering a Complex System. Outcomes such as the multiple events that have taken place in Ukraine, affecting not only the country in which they emerged, hence turning into a major geopolitical issue, cannot be reduced to

the sole fact of Viktor Yanukovich’s decision not to cooperate to a deeper extent with the European Union.

To enter in the perilous domains of causality when facing any sort of event within the International System is misleading. It is not possible to determine the exact cause of any given fact just by the nature of the consequences (Salmon, 1998, p. 13), nor can we be completely sure of the outcome of any given impulse. Wesley Salmon, being influenced by the ideas of Carl G. Hemper, came up with an alternative way of analyzing causality, which more than alternative turned out to be complementary to the non-co relational thoughts of David Hume, thoughts that have been the milestone of the preceding arguments.

Salmon agrees to a great extent with Hume’s reflections on the impossibility of

finding a direct connection between cause and effect, to which he adds a new concept that

emerged from a loophole he found in Hume’s assertions. Statistical correlations, as Salmon

decided to present them, are relevant indicatives of causal relations of some sort between the symptoms4 of a cause and the subsequent outcome. (Salmon, 1998, p. 45) For instance, feeling chills is a symptom associated with the developing of influenza, as it is also associated to having feelings for another individual, as well of being related to the popular

expression of experimenting a hunch. As Salmon says “there are distinct effects to a common cause, and the common cause explains the statistical relation” (1998, p. 45).

When correlated with the actual outcome, which let’s say turned out to be a respiratory infection, those chills have a statistical relevance when looking for the causes of the infection, which is not the same as asserting that the chills caused the disease. It all turns into a matter of statistical probability. Regarding the situation in Ukraine, the increase in reverse gas flow between the Visegrad countries and Ukraine is the symptom of a failure in the Ukrainian strategies of energy security; as well of being a symptom of the renewed will of cooperation among the V4 and Kiev; as could also be symptom of the

rapprochement that is intended with both the V4+ platform and the gradual enforcement of the EU Association Agreement.

A structuralist theory of International Relations, such as neorealism, would most likely find the reverse gas flow as a way in which the Visegrad providers exercise their power over Ukraine, which is not self-capable of producing their own energy, thus placing it in a category hierarchically inferior to that of the gas providers. Classical realism, in the meantime, would find obnoxious and irrational that Ukraine would not engage in a military confrontation with the gas provider so that the State could gain the property of the energy source. The latter given that the procurement of energy is a national interest, however secondary or tertiary to the military security, of course.

It is due to the previously illustrated arguments that Complexity was chosen as the theoretical frame in the making of this work. The situation that Ukraine has had to sort out since 2013 is perfectly unable to be seen as premeditated. No existing theory of International Relations could have predicted such an escalation of events. Neither, of course, could have Complexity because ungrounded predictions are exactly what the theory tries to avoid.

The unpredictability of the complex International System is based on the emergent

properties that can appear in form of a leader’s decision, the securitization of a certain issue

4. THE VISEGRAD-UKRAINE COMPLEX SYSTEM: ADAPTABILITY IN MOTION

Interactions among actors are what nourish the International System. The way in which they behave and self-organize in due course to the emergent events they constantly face, is what ends up building their relationships. Ultimately, actors compose the System and their interactions are the System (a complex one, certainly).

Within a macro-complex system such as the International System, a variety of Complex sub-systems rely, which are formed by the interdependent interactions that certain actors have managed to establish among themselves. As stated by Kavalski (2007, p. 438),

“complex systems are not uniform—there are relationships of differing strengths between their components (and those with especially tight connections form sub-systems”. Well, one of those sub-systems is the Visegrad-Ukraine Complex System.

The Visegrad countries demonstrate, as they did throughout most of the Cold War, that their geographical positioning haunts them relentlessly. Not even after gaining their awaited independence have they managed to build a proper and own Russian and European foreign policy as these four countries seem to be fated to perpetually shift from one corner of Europe to the other. Mohammed Ayoob (1989), noted International Relations scholar, would refer to this ambivalence as ‘schizophrenia’. However, Ayoob’s State schizophrenia refers to the dual role that Third World States take regarding, on the one hand, the distribution of capabilities and resources within the structure and, on the other, their role as States and the destabilizing consequences that said redistribution may have on them. (p. 70)

Continuing on the line of Ayoob’s psychological reference one would be tempted to

assert that the ambivalence in the foreign policy of the Visegrad Group in regard of the situation that emerged in Ukraine in 2013, is to be called hypocritical. The latter given that the Group has condemned the actions that Russia has taken in eastern Ukraine followed by