Effects of immediacy of feedback on estimations and performance

Pablo Fajfar,1Guillermo Campitelli,3and Martin Labollita2

1Facultad de Ciencias Empresariales, Universidad Abierta Interamericana and2Facultad de Ciencias Economicas,

Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina, and3School of Psychology and Social Science, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Western Australia, Australia

Abstract

We investigated the role of anticipation of feedback in performance and estimation about own performance. We submitted 155 participants to a test of verbal aptitude, and we requested them to give estimations of their own performance and the performance of other participants. There were two treatments: immediate feedback and delayed feedback. Participants in the immediate-feedback group were informed that they would receive feedback on their performance immediately after finishing the test, whereas participants in the delayed-feedback group were informed that they would receive feedback a week after taking the test. The immediate-feedback group performed better than the delayed-feedback group. Furthermore, the former underestimated their own performance. On the other hand, participants on the delayed-feedback group made unbiased estimations. We present a mathematical model based on construal-level theory, decision affect theory, temporal discounting, and Moore and Healy’s model of overestimation. The model suggests that the source of differences in performance and in estimations of own performance is a construal of the feedback situation that modifies the expected utility of the task.ajpy_481..9

Key words:decision affect theory, immediate feedback, judgement, overconfidence, performance, temporal discounting

People make predictions and estimations of events every day. We predict how long errands will take in order to plan how many of them we can do in a day. We estimate the freshness of a vegetable based on its colour. Of particular interest are the estimations and predictions about ourselves: How well did I do in a job interview? How successful will my diet be? Will I be able to graduate? How successful would I be in the future? How well did I do in the midterm exam? Research have found that we are overoptimistic on these types of judgement (e.g., Griffin & Tversky, 1992; Keren, 1997; Lichtenstein, Fischhoff, & Phillips, 1982; Moore & Healy, 2008; Perloff, 1987; Weinstein, 1980; Yates, 1990). Researchers have also found that estimations and predic-tions about our own performance (henceforth, performance judgements) depend, among other factors, on the temporal distance between the performance judgement and the task (e.g., Gilovich, Kerr, & Medvec, 1993), or the temporal dis-tance between the performance judgement and the moment in which feedback about performance (henceforth, perfor-mance feedback) would be received (e.g., Shepperd, Grace,

Cole, & Klein, 2005; Shepperd, Ouellette, & Fernandez, 1996).

Gilovich et al. (1993) showed that a group of students overestimated their own performance in an exam when their performance judgements were made in advance, and that the overestimation significantly decreased when the performance judgements were made immediately before the exam. Shepperd et al. (1996) showed that students overestimated their qualifications on a classroom exam a month before taking the exam. However, they were more accurate when they estimated their performance immedi-ately after taking the exam. Interestingly, they underesti-mated their performance when the estimation took place 3 days after taking the exam and seconds before receiving performance feedback. Shepperd et al. (2005) showed that participant’s knowledge of when they would receive feedback about a test affected performance judgements about that test. They asked participants to perform a verbal reasoning analogies test. After taking this test, a group of participants were told that they would receive immediate feedback, and another group of participants were told that they would receive feedback in 3 days. Participants in the immediate-feedback group estimated their performance accurately, and participants in the delayed-feedback group overestimated their performance. Moreover, there was a negative significant correlation between anxiety and over-estimation (i.e., the more anxious the participants, the less they overestimated).

Correspondence: Guillermo Campitelli, PhD, School of Psychology and Social Science, Edith Cowan University, Perth, WA 6027, Australia. Email: g.campitelli@ecu.edu.au

Received 11 May 2011. Accepted for publication 8 December 2011.

© 2012 The Australian Psychological Society

These studies suggest that feedback plays an important role on performance judgements. Feedback could also play an important role on performance itself. Indeed, research onto the role of feedback on performance has been very prolific, with several published meta-analyses (e.g., Kluger & DeNisi, 1996) and reviews of meta-analyses (e.g., Hattie & Timperley, 2007). A typical finding in this field of research is that, in general, immediate performance feedback leads to better learning than delayed performance feedback (e.g., Kulik & Kulik, 1988). There are diverse explanations for this effect (e.g., feedback interventions lead to changes in locus of attention; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996), but they all have in common that they focus on how feedback interventions about precedent trials affect performance in subsequent trials. However, it is possible that performance on a trial is not only influenced by the feedback received in previous trials, but also by the expectation or anticipation of the participants regarding the feedback that they will receive after completing the present trial. That is, the expectation of receiving immediate feedback may lead to a different effect on performance than the expectation of receiving delayed feedback.

These two lines of research investigate different aspects about the timing of feedback: The first one is interested in the role of feedback on performance judgements, the second one in the role of feedback on performance. A simple change in the methodology used in research onto the role of feed-back on performance judgements could investigate how anticipation of feedback could affect both performance and performance judgements. Instead of informing the parti-cipants about the timing of feedback after the task, this information could be given before the task. Thus, this information could potentially affect both performance in the task and the subsequent performance judgement. Given its important practical implications—for example, the fact that a very simple intervention may improve performance could be applied in educational settings and to improve performance in psychological experiments, among other interventions—it is surprising that this has only been recently reported in a short article. Kettle and Häubl (2010)1 asked participants to make predictions about their future performance in an oral presentation 15, 8, or 1 day before the presentation. Before making their predictions, they were informed about the day they would receive performance feedback. This ranged from the same day of the presentation to 17 days after the presentation. Kettle and Häubl found a linear negative relationship between the delay of feedback and performance. Contrarily, they found a positive relation-ship between the delay of feedback and predicted per-formance. That is, the participants who expected delayed feedback were more optimistic and worse performers than those who expected immediate feedback. Moreover, this study replicated Gilovich et al. (1993) and Shepperd et al.

(1996) results that participants who made their predictions in advance (15 days prior the presentation) were more opti-mistic than those who predicted their performance the day before the presentation.

OVERVIEW OF THE PRESENT STUDY

The present study extends Shepperd et al.’s (1996, 2005) research onto the influence of timing of feedback on per-formance judgements. The first aim of this study was to replicate Shepperd et al.’s (1996, 2005) findings that the temporal distance between a task and feedback affects per-formance judgements. Sweeny, Carroll, and Shepperd (2006) proposed a number of explanations of those find-ings, some of which are applicable to the present study. First, based on construal-level theory (CLT) (Trope & Liberman, 2003), they proposed that people construe distant events abstractly and that this construal focuses on what people would like to happen. On the other hand, near events are construed more concretely, and this con-strual focuses on what is likely to happen. Second, when the feedback situation is immediate, people often experi-ence an increase in anxiety and may judge their per-formance based on their current level of anxiety. Third, as Shepperd and McNulty (2002) have shown, people feel more disappointed when outcomes fall short of expecta-tions than elated when outcomes exceed expectaexpecta-tions. When feedback is immediate, people may try to avoid dis-appointment by shifting expectations downwards. Fourth, people may adopt the strategy of defensive pessimism (Norem & Cantor, 1986), which consists of feeling pessi-mistic about a future outcome in order to mobilise energy to avoid an undesired outcome.

METHOD

Participants

One hundred and fifty-five students (72 females) of Eco-nomics and Social Sciences from the Universidad of Buenos Aires, Universidad Católica Argentina, and Universidad Abierta Interamericana participated in the study. Students were recruited by advertisements in web pages of these universities. The experimental sessions were carried out at a laboratory of the Facultad de Ciencias Economicas, Univer-sidad de Buenos Aires.

Material

Participants were submitted to the BAIRES test of verbal aptitude (Cortada de Kohan, 2003). This test contains 34 multiple choice items with one correct option and three incorrect options per item. The first 17 items present a noun and four options of possible definitions. The 17 remaining items present a noun and four options of possible synonyms.

Procedure

Participants were randomly allocated to two treatments: immediate feedback (79 participants;Mage=22.2,SD=4.28; 35 male) and delayed feedback (76 participants; Mage= 24.81,SD=4.9; 49 male). In both treatments, we requested the participants to choose an option in each of the 34 BAIRES items and to indicate, after they finished the whole test, the number of items they believed they answered cor-rectly, to estimate the number of correct answers that the other participants of this study answered correctly, on average, and to indicate how difficult the test was for them. For every correct item, participants were paid $1, without discounting any monetary value for the incorrect items. Before starting the BAIRES test, we informed the partici-pants of both groups that they would receive the money they earned a week after the experiment was carried out. We also informed the participants in the immediate-feedback group that they would receive feedback on the number of correct items immediately after finishing the test. On the other hand, participants in the delayed feedback treatment were informed that they would receive feedback on the number of correct items a week after the experiment.

Variables

The dependent variables wereperformance,estimation (own), estimation (others),difficulty,bias, andsocial comparison. Perfor-mancewas measured as the number of correct items. Estima-tion (own)was measured as the participant’s estimations on

how many correct items they had answered correctly. Estimation (others) was measured as the estimation of the number of correct items that other participants of the experi-ment responded correctly, on average. Difficulty was mea-sured as the reported difficulty of the test on a scale from 1 to 10.Biaswas calculated as the difference between estima-tion on own performance and actual performance in each participant. Positive bias values were considered overconfi-dent estimations, 0 values were considered unbiased estima-tions, and negative values were considered under-confident estimations. (Note that in other studies, overconfidence was called ‘optimism’, unbiased estimations were called ‘realis-tic’, and underconfidence was called ‘pessimism’). Social comparisonwas calculated as the difference between estima-tion of own performance and estimaestima-tion of performance of others in each participant. Positive values indicate that the participants believed that they performed better than the average of other participants, and negative values indicate that the participants believed they performed worse than the average of other participants.

RESULTS

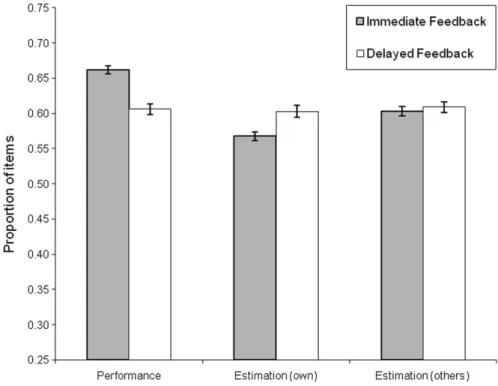

The immediate-feedback group estimated, on average, that they answered correctly 9.1% items less than the actual percentage of correct items (M= -0.09,SD=0.11), whereas the delayed-feedback group was, on average, unbiased (M= -0.00, SD=0.12). The difference in bias values between treatments was significant (t(153)=4.82,p<.001, Cohen’sd=0.77). Therefore, the immediate-feedback group was, on average, underconfident, and the delayed-feedback group was, on average, unbiased.

The number and percentage of overconfident, unbiased, and underconfident participants in each group were 11 (14%), 8 (10%), and 60 (76%), respectively, in the immediate-feedback group; and 35 (46%), 7 (9%), and 34 (45%), respectively, in the delayed-feedback group. As the average age of the immediate-feedback group was lower than that of the delayed-feedback group, and there were relatively more female in the former than in the latter, these results may be accounted for by the variables age or gender, and not by the treatments. In order to rule out this

possi-bility, we run correlational analyses between age and gender, and performance and estimation (own) in the whole sample. None of these correlations was significant: performance-gender (male 1 – female 0), r (153)=0.13, p=.109; performance-age,r(153)=0.14,p=.073; estimation (own)-gender, r (153)=0.08, p=.328; estimation (own)-age, r(153)=0.14,p=.078. Even if the correlations were signifi-cant, this would not affect our conclusions. In this sample, men and older people tended to perform better and to give higher estimations than women and younger people. As the immediate-feedback group had more women and younger participants, the higher performance in this group could not be explained by age or gender.

There were no significant differences between groups in perceived difficulty (see Table 1). In the immediate-feedback group, there was a worse-than-average effect (see Moore, 2007; Moore & Small, 2007 for an explanation of this effect). That is, participants in this group estimated that their performance was worse than the performance of other par-Table 1 Means, standard deviations, and comparisons between the immediate-feedback group and the delayed-feedback group

Immediate feedback

Delayed feedback

Comparison immediate-delayed

Performance 0.66 (0.11) 0.61 (0.13) t(153)=2.96;p=.003

Estimation (own) 0.57 (0.12) 0.60 (0.15) t(153)=1.55;p=.123

Bias -0.09 (0.11) -0.00 (0.12) t(153)=4.82;p<.001

Difficulty 6.30 (1.25) 6.05 (1.44) t(153)=1.15;p=.250

Estimation (others) 0.60 (0.12) 0.61 (0.13) t(153)=0.21;p=.835

Social comparison -0.04 (0.12) -0.01 (0.15) t(153)=1.34;p=.183

Note. Means and standard deviations (in brackets) for the immediate and delayed-feedback treatments. The scale used in difficulty was 1–10; average proportion of correct answers is reported in all the other variables.

ticipants (comparison estimation (own) vs estimation (others) in the immediate-feedback group: t (78)=2.59; p=.012, Cohen’s d=0.30). The comparison between esti-mation of own performance and performance of others was not significant in the delayed-feedback group (t(75)=0.33; p=.74, Cohen’s d=0.04). On average, the social compari-son in the immediate-feedback group was -0.04, whereas the social comparison in the delayed-feedback group was almost zero (-0.01). The number (and percentage) of par-ticipants with positive, zero, and negative values in social comparison in each group were 23 (29%), 14 (18%), and 42 (53%), respectively, in the immediate-feedback group; and 37 (49%), 5 (6%), and 34 (45%), respectively, in the delayed-feedback group.

Summing up, the participants in the immediate-feedback group performed better than those in the delayed-feedback group, they underestimated their own performance, and they believed that other participants performed better than them. On the other hand, participants in the delayed-feedback group were unbiased on their estimations, and they considered that the performance of others was similar to their own performance.

DISCUSSION

Two main results were found in this study. First, a group of participants who were informed that they would receive immediate performance feedback had a better performance than a group of participants who were informed that they would receive performance feedback a week after the task. Second, the former underestimated its performance, whereas the latter showed no bias in its performance judgement. The first result replicates a novel finding. Kettle and Häubl (2010) informed students that (and when) they would receive feed-back in an oral presentation before the presentation. The temporal distance between the presentation and feedback varied from 0 to 17 days. They found that the student’s performance in the oral presentation was negatively related to the temporal distance between the presentation and feed-back. This result is also in accordance with the finding that, in the majority of cases, immediate feedback leads to better learning than delayed feedback (e.g., Kulik & Kulik, 1988).

The second result accords with previous studies on the role of anticipation of feedback in performance judgements (i.e., Shepperd et al., 1996, 2005). We presented earlier a number of factors that Sweeny et al. (2006) indicated as candidates to explain this effect. One of these factors, defen-sive pessimism (Norem & Cantor, 1986), suggests that as feedback draws near, people tend to adopt pessimism about their performance. One of the possible effects of this strategy is that people mobilise energy to work hard and avoid nega-tive feedback. We hypothesised that, if this is the case, we

should find a reduction of overconfidence and an increase in performance in the immediate-feedback condition. Our results support this hypothesis.

Another interesting result of our study is the significant worse-than-average effect (see Moore & Small, 2007 for an explanation) in the immediate-feedback group. Participants in this group estimated that their performance was worse than that of the other participants. Moore (2007) presented a model in which estimation on our own performance and estimation of performance of others are related. He suggested that when overconfidence is observed, worse-than-average effect is expected, and when under-confidence is observed, better-than-average effect is expected. This is partly explained by Gigerenzer, Hoffrage, and Kleinbölting’s (1991) proposal that performance is a variable phenomenon that changes according to task characteristics, whereas esti-mation on own performance is less variable: It is not only influenced by current performance but also by previous performance in similar tasks. This is what happened in our study: There were no differences in estimations of own per-formance between treatments even though there were dif-ferences in actual performance. Moore suggested that, given that we have less information for estimating performance of others, our estimation of others’ performance is more regres-sive to the previous experience to similar tasks. That is, we evaluate the performance of others based on our prior expe-rience with similar tasks, and our current performance does not affect this estimation. Our experimental manipulation had the opposite effect: We found underconfidence and worse-than-average effect in the immediate-feedback group that performed better than the delayed-feedback group. A possible explanation of this result is that the anticipation of immediacy of feedback affects only the estimation of our own performance because we are not expected to know how other people perform, but we are expected to know how we perform. Another possible explanation of differences with Moore’s study is methodological: We asked participants to estimate the average performance of other participants of the experiments, and Moore asked his participants to estimate the performance of a random participant.

Anticipation of affect and temporal discounting: An explanation and a mathematical model

Like Sweeny et al. (2006), we suggest that the effects of anticipation of feedback are partly explained by a difference in the construal of the feedback situation. CLT (Trope & Liberman, 2003) proposes that people construe concrete and contextualised models of near-future events, and abstract and decontextualised models of distant-future events. In the present study, participants on the immediate-feedback group may have construed a more concrete representation of the feedback situation than that of the delayed-feedback group. This difference in representation of the feedback situation may have led to a difference in the subjective expected benefit of carrying out the task. We refer to this as the expected utility of the task (EUT). In order to formalise the difference in representation, we use the concept of temporal discounting. This concept refers to the fact that the utility of events (e.g., receiving money) varies as a function of time. For example, receiving $10 now is considered to have more utility than receiving the same amount a week later. Equally, losing $10 is considered to have a more negative utility than that of losing $10 a week later. In our study, the temporal discount of the monetary reward should not have differed between groups because all the participants were informed that they would receive the monetary reward a week after the experiment. We propose that the difference in represen-tation between groups arose from the represenrepresen-tation of the feedback situation. Given that the performance feedback was expected to be received at different times in each group, the expected benefit or displeasure of the feedback situation differed between groups. We formalise these hypotheses as follows:

EUT= × +X δ f l

( )

×γ, (1) where the EUT equals the sum of the product of the expected score (X) and the discount rate of the monetary reward (d), and the product of the utility of feedback func-tion (f(l)) and the temporal discount rate of feedback (g) which, unliked, varies between groups. This formula con-tains aspects of temporal discounting and aspects of Moore and Healy’s (2008) model of overconfidence. These authors proposed that just before performing a task, people form a belief about the score they would obtain in this task. This belief is composed of the average global score and the varia-tion of the individual’s scores from the global score (i.e., Xi=S+Li, whereXirepresents the person i’s prior belief on his/her performance in the task, S represents the average global score in the task, andLi represents the individual’s belief on how much his/her score would deviate from the global score). In the first part of equation 1, no differences between groups are expected because the temporal discount rate of the monetary reward is the same in both groups and,given the random allocation of the participants to the groups, differences in prior beliefs are unlikely.

The second part of the equation differentiate between groups because the rate of temporal discount of feedback differs between groups (i.e., 0<gd<1 in the delayed-feedback group, and gi=1 in the immediate-feedback group). This discount rate modifies the utility of feedback function (f(l)) by making it less extreme in the delayed-feedback group. This function is related to the expected performance because in the present study, expecting to obtain a certain score implies expecting to receive a certain feedback. We define the utility of feedback function as follows:

f l L L

L L

( )

= ≥− <

⎧ ⎨ ⎪ ⎩⎪

i kp

i

i kn

i

if

if ,

, ,

0

0 (2)

where 1<kp<kn are free parameters. This formula indi-cates that expecting to perform above the global average (S) (i.e.,Li>0) increases utility, and expecting to perform below the global average (i.e., Li<0) decreases utility. Moreover, it is assumed that kn>kp, thus the increase in utility due to expecting to perform a unit higher than average is lower than the decrease in utility due to expecting to perform a unit lower than average. This assumption is based on the decision affect theory and is in line with prospect theory (Tversky & Kahneman, 1979), which proposes that people take more risks to avoid losses than risks to obtain gains (i.e., loss aversion). Therefore, theEUTwill be higher for partici-pants who expect to perform above average than for the participants who expect to perform below average. Given that the delayed-feedback group temporally discounts the utility of feedback, their EUT is lower than that of the immediate-feedback group for participants who expect to perform above average, and higher for participants who expect to perform below average.

Given that theEUT is more extreme in the immediate-feedback group, the participants in this group had more motivation to perform above average and to avoid perform-ing below average than those in the delayed-feedback group. As suggested by Norem and Cantor (1986), this may have affected the energy mobilised to perform the task. We for-malise this as

ˆ

G= ×T M (3)

caused by motivation, and that this is explained by the rate of temporal discounting of feedback.

The change in theEUTproduces another effect: The par-ticipants in the immediate-feedback group take into account the anticipation of the feedback situation in their perfor-mance judgements. This leads to an adjustment on their performance judgements to avoid the disappointment that could arise if they give a performance judgement that is higher than the performance feedback they would receive immediately. This is in line with Sweeny et al.’s (2006) pro-posal that people shift their expectations downwards to avoid disappointment, and with Norem and Cantor’s (1986) concept of defensive pessimism. We formalise this by

ˆ ,

J=d y

( )

× + × −α Y(

1 α)

(4) where the predicted performance judgement (Jˆ) equals the weighted sum of the anticipated disappointment (d(y)) and the belief about performance generated immediately after performing the task (Y), and a (02a21) is the relative weight given to the feedback situation.Y was proposed by Moore and Healy (2008), and corresponds to an internal signal or ‘gut feeling’ about our own performance that we get after performing a task. For simplicity, we also follow their proposal that this signal is, on average, unbiased; however, releasing this constraint does not change our con-clusions. The interpretation of the anticipation of feedback (d(y)) is given with the following example. After performing a task, a participant has the gut feeling (Y) that he/she answered 25 questions correctly. Because he/she knows that this signal is not perfect, he/she would tend to adjust his/her performance judgement to avoid the disappointment of receiving a feedback lower than the judgement. Thus, instead of solely using his/her internal signal to make a performance judgement, he/she also considers the possible disappointment (d(y)) that using his/her internal signal y as a performance judgement could generate. This possible disappointment is represented asd y

( )

={

[

(

Σq h y( )

,)

/N]

1 kn/}

γ, (5) where N is the number of all the possible feedback (i.e., N=35) andq h y h y h y

h y h y

, ,

, ,

(

)

=(

−)

− ≥−

(

−)

− <⎧ ⎨ ⎪ ⎩⎪

j m

kp

j m

j m

kn

j m

if

if

0

0 (6)

whereq(h,y) is the function that relates each possible judge-ment that could be made using all the possible internal signals y(where m=0 to 34) and all the possible feedback to be received h (where j=0 to 34). Following decision affect theory, if the feedback is higher than the performance judge-ment, there would be elation (or an increase in utility), and if

the feedback is lower than the performance judgement, there would be disappointment (or decrease in utility). Equation 5 indicates that the anticipated disappointment given the inter-nal siginter-nalyis the summation of all the possible instances of disappointment or elation that could occur if one usesyas a performance judgement. For example, using the internal signal y=25 could lead to 24 instances of disappointment (i.e., if the actual performance, and therefore the perfor-mance feedback, is between 0 and 24), one neutral instance (if performance equals 25), and nine possible instances elation (i.e., if the actual performance is between 26 and 34). Put simply, giving high performance judgements has a higher probability of disappointment and a lower probability of elation, and the reverse is true for low performance judge-ments. Equation 5 also indicates that this function varies between groups because of the rate of temporal discounting of feedback. Returning to equation 4, we hypothesised above that the participants in the immediate-feedback group took into consideration the feedback situation when they were making their performance judgements to a higher extent than the delayed-feedback group. This means thatashould be higher in the immediate-feedback group.

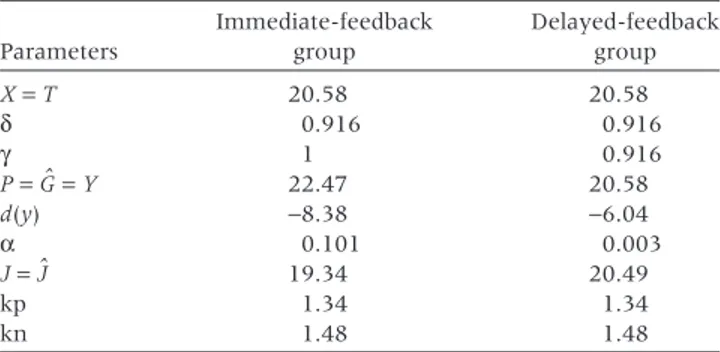

Given that the purpose of developing the model was to formalise hypotheses rather than testing them, we only fit the model to the data at the group level. We first solved equation 3. It was assumed that the average performance in similar tasks in the past for the whole sample (T) was the same as the average actual performance in the delayed-feedback group in the present task, thusT=20.58. As the participants were randomly allocated to groups, we assumed that T was the same in both groups. Given that the immediate-feedback group received feedback immediately after the task, their temporal discount rate of feedback was 1. We calculatedgdby fitting the model to the average value of performance in each group. The obtained value was gd=0.916.

for each group. The model fitted the data perfectly with ai=0.101 andad=0.003. Table 2 shows the values of all the parameters for each group. This result supports the hypoth-esis that the participants in the immediate-feedback group paid relatively more attention to the possible disappointment in the feedback situation.

Limitations

This model has a number of limitations. First, the goal of developing the model was to give an explicit account of the results and to guide future investigation, thus the experi-ment was not designed to test the model. Second, given the descriptive nature of the model, we did not fit the model to the individual data. Third, we made some assumptions based on previous research, but other assumptions are probably too simplistic. Fourth, we chose a task in which an increase in motivation could lead to performance improvement. Although the increase in performance due to motivation is possible in many tasks, it does not apply to all types of tasks. That is, increase in motivation does not always improve performance. These limitations should be considered in the context of the advantages of developing a mathematical model to explain these results. First, no formal explanation of this effect has been proposed earlier, and second, this model could be used to derive experimental hypothesis in future research.

CONCLUSIONS

Sweeny et al. (2006) proposed a number of explanations for the effect of immediate feedback on performance

judge-ments, some of which are applicable to the present study: different construal of feedback situation, increase in anxiety, avoidance of disappointment, and defensive pessimism. Norem and Cantor (1986) suggested that the strategy of defensive pessimism may lead to mobilise energy to work hard in order to avoid an undesired outcome. We suggested that, if this suggestion is correct, it would be possible to find pessimism (i.e., underconfidence) and increase in per-formance due to anticipation of immediate feedback. Our results support this hypothesis. We incorporated this expla-nation and two of the other three explaexpla-nations into a math-ematical model that accounts for the effects of anticipation of feedback on performance and performance judgement. We did not incorporate the anxiety explanation because we did not measure anxiety in our experiment.

The model suggests that the source of both performance improvement and underconfidence in the immediate-feedback group is a representation of the immediate-feedback situa-tion that affected the EUT. This utility was higher in the immediate-feedback group in comparison to the delayed-feedback group in situations in which performance delayed-feedback is higher than expected performance, and lower in situations in which performance feedback is lower than expected per-formance. This is because the immediate-feedback group discounted the pleasure of the monetary reward but not the elation/disappointment of the feedback situation, whereas the delayed-feedback group discounted both. This had two effects: First, the participants in the immediate-feedback group were more motivated to perform the task, and second, when they had to make a performance judgement, they paid relatively more attention to the anticipation of feed-back. This lead to adjusting their performance judgements downwards.

Being aware of the limitations of this study, we suggest that our results have theoretical and practical implications. From the theoretical standpoint, we extended decision affect theory (Mellers et al., 1997, 1999) to anticipation of feed-back. This theory indicates that the pleasure obtained by an outcome is a function of the prior expected outcome and the actual outcome. We proposed that people also anticipate the pleasure or utility of carrying out a task. We used aspects of decision affect theory together with the concept of temporal discounting, Moore and Healy’s (2008) model of overconfi-dence, and Trope and Liberman’s (2003) CLT to formalise this proposal. Our results also contribute to the field of research onto the effect of timing of feedback on per-formance. We proposed that anticipation of feedback could partly explain the improvement of performance in immediate-feedback conditions.

The practical implication is that informing on the timing of feedback before participating in a task could cause very important effects: performance improvement and undercon-fidence. This is relevant for educational settings. Although Table 2 Fitted, obtained, or assumed values of variables or

para-meters in the mathematical model

Parameters

Immediate-feedback group

Delayed-feedback group

X=T 20.58 20.58

d 0.916 0.916

g 1 0.916

P=Gˆ =Y 22.47 20.58

d(y) -8.38 -6.04

a 0.101 0.003

J=Jˆ 19.34 20.49

kp 1.34 1.34

kn 1.48 1.48

Note. X is the expected outcome, T is the average performance in similar tasks in the past,dis the temporal discount rate of the monetary value,gis the temporal discount rate of the feedback situation,Pis the actual performance,Gˆ is the predicted performance,Yis the internal signal about performance generated immediately after finishing the task,

future research is needed to investigate the nature and the boundary conditions of this effect, psychologists may find useful to inform their participants that they would receive immediate feedback.

NOTE

1. We carried out the experiment before Kettle and Häubl’s (2010) article was published; thus, our hypothesis was elaborated independently from those in this study.

REFERENCES

Berns, G. S., Laibson, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2007). Intertemporal choice—toward an integrative framework. Trends in Cognitive Sciences,11, 482–488.

Cortada de Kohan, N. (2003).BAIRES. Test de Aptitud verbal. Madrid: TEA.

Gigerenzer, G., Hoffrage, U., & Kleinbölting, H. (1991). Probabilistic mental models: A Brunswikian theory of confidence.Psychological Review,98, 506–528.

Gilovich, T., Kerr, M., & Medvec, V. H. (1993). Effect of temporal perspective on subjective confidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,64, 552–560.

Griffin, D., & Tversky, A. (1992). The weighting of evidence and the determinants of confidence.Cognitive Psychology,24, 411–435. Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback.Review of

Educational Research,77, 81–112.

Keren, G. (1997). On the calibration of probability judgments: Some critical comments and alternative perspectives.Journal of Behav-ioral Decision Making,10, 269–278.

Kettle, K. L., & Häubl, G. (2010). Motivation by anticipation: Expecting rapid feedback enhances performance. Psychological Science,21, 545–547.

Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interven-tions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory.Psychological Bulletin,

119, 254–284.

Kulik, J. A., & Kulik, C. L. C. (1988). Timing of feedback and verbal learning.Review of Educational Research,58, 79–97.

Lichtenstein, S., Fischhoff, B., & Phillips, L. D. (1982). Calibration of subjective probabilities: The state of the art up to 1980. In

D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, & A. Tversky (Eds.), Judgment under

uncertainty: Heuristics and biases (pp. 306–334). New York:

Cambridge University Press.

McGraw, A. P., Mellers, B. A., & Ritov, I. (2004). The affective costs of overconfidence.Journal of Behavioral Decision Making,17, 281– 295.

Mellers, B. A., Schwartz, A., Ho, K., & Ritov, I. (1997). Decision affect theory: Emotional reactions to outcomes of risky options.

Psychological Science,8, 423–429.

Mellers, B. A., Schwartz, A., & Ritov, I. (1999). Emotion-based choice.Journal of Experimental Psychology: General,128, 332–345. Moore, D. A. (2007). Not so average after all: When people believe

they are worse than average and its implications for theories of bias in social comparison.Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,102, 42–58.

Moore, D. A., & Healy, P. J. (2008). The trouble with overconfi-dence.Psychological Review,115, 502–517.

Moore, D. A., & Small, D. A. (2007). Error and bias in comparative judgment: On being both better and worse than we think we are.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,92, 972–989.

Norem, J. K., & Cantor, N. (1986). Defensive pessimism. Harnessing anxiety as motivation.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

51, 1208–1217.

Perloff, L. S. (1987). Social comparison and illusions of invulner-ability to negative life events. In C. R. Snyder & C. E. Ford (Eds.),

Coping with negative life events: Clinical and social psychological pers-pectives(pp. 217–242). New York: Plenum Press.

Shepperd, J. A., Grace, J., Cole, L. J., & Klein, C. (2005). Anxiety and outcome predictions.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,

31, 267–275.

Shepperd, J. A., & McNulty, J. K. (2002). The affective consequences of expected and unexpected outcomes.Psychological Science,13, 85–88.

Shepperd, J. A., Ouellette, J. A., & Fernandez, J. K. (1996). Abandoning unrealistic optimism: Performance estimates and the temporal proximity of self-relevant feedback.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,70, 844–855.

Sweeny, K., Carroll, P. J., & Shepperd, J. A. (2006). Is optimism always best? Future outlooks and preparedness.Current Directions in Psychological Science,15, 302–306.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2003). Temporal construal.Psychological Review,110, 403–421.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk.Econometrica,47, 263–292.

Weinstein, N. D. (1980). Unrealistic optimism about future life events.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,39, 806–820. Yates, J. F. (1990).Judgment and decision making. Englewood Cliffs,