EFL Eleventh Graders’ Decision-Making via Critical Literacy Practices:

A Study of their Social Agency

Marcela Liliana Cárdenas Cruz

20161062002

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

School of Science and Education

MA in Applied Linguistics to the Teaching of English

EFL Eleventh Graders’ Decision-Making via Critical Literacy Practices:

A Study of their Social Agency

Marcela Liliana Cárdenas Cruz

20161062002

Thesis Director: Álvaro Hernán Quintero Polo. PhD.

A thesis submitted as a Requirement to Obtain the Degree as M.A.

in Applied Linguistics to the Teaching of English

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

School of Science and Education

MA in Applied Linguistics to the Teaching of English

NOTE OF ACCEPTANCE

Thesis Director:

Álvaro Hernán Quintero Polo. PhD.

Jury:

UNIVERSIDAD DISTRITAL FRANCISCO JOSÉ DE CALDAS

Acuerdo 19 de 1988 del Consejo Superior Universitario

Artículo 177. “La Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas no será responsable de las

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my profound gratitude to the professors-researchers of the Master

Programme in Applied Linguistics to TEFL for their immense contributions that have helped me

succeed in my academic pursuits at the Distrital University.

My special appreciation and thanks to my director, Dr. Alvaro Quintero Polo for his

insightful support, questions and guidance in getting me along the way of this research project.

To him all my admiration, respect and affection.

All my love to my family and to my close friends, pieces of heaven God gave me; this

journey would have been a completely different experience without them. For their love and

faith in me even when sometimes looked as if I had lost sight of what is really important in life:

people who love you. However, they have always encouraged me to pursue my dream and

supported me in every possible way.

Finally, I would like to mention my students, specially the focal participants. I want to

thank them for all their cooperation and valuable insights which, in turn, made this study

Abstract

This thesis reports on a qualitative-research study in a private school in Bogotá that

accompanied the development of small-scale projects by teenagers. Within the Critical

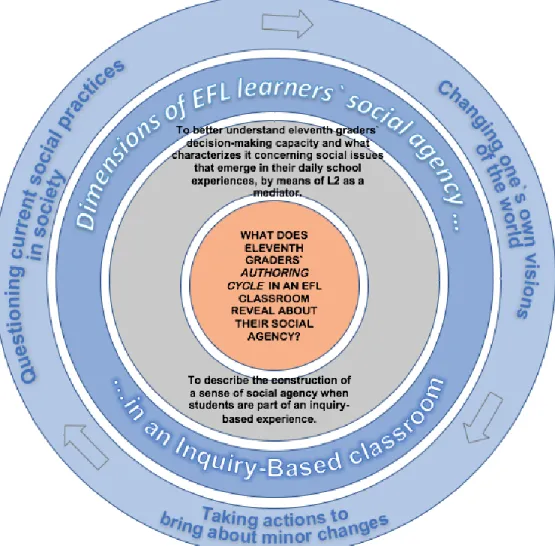

Pedagogy perspective, it examines the question: What does eleventh graders’ Authoring Cycle in

an EFL classroom reveal about their social agency? and aims at better understanding learners’ decision-making capacity and what characterizes it concerning social issues that emerge in their

daily school experiences by means of L2 as a mediator. Analysing the data teenagers themselves

become co-interpreters of their own semi-structured interviews and written reports. The

interpretive inductive approach served as the framework; findings address the interplay of

learners’ decision-making capacity and their social agency sense to improve the surrounding

context.

Key Words: Critical Pedagogy, Inquiry Based Pedagogy, Learner Informed Decision-Making,

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract... 6

Introduction ... 12

Chapter 1 ... 14

Statement of the Problem ... 14

Research Question and Objectives... 16

Rationale ... 17

Background to the Study ... 18

Chapter 2 ... 25

Literature Review ... 25

... 25

Students who make their own informed decisions are characterized as social agents ... 25

Literacy development as a practical realization of agency ... 36

Chapter 3 ... 43

Research Design ... 43

Type of Study ... 43

Setting ... 44

Participants ... 45

Role of the Researcher ... 45

Ethical Issues ... 46

Data Collection Instruments and Procedures ... 46

Chapter 4 ... 48

Instructional Design ... 48

Educative Setting ... 48

Teaching Approach ... 48

Vision of Language ... 49

Vision of Teaching ... 50

Vision of Learning ... 50

The Pedagogical Intervention as a tool for innovation ... 51

Chapter 5 ... 60

Data Analysis ... 60

Data Management ... 60

Framework of Analysis ... 61

Validation Process ... 62

Findings... 63

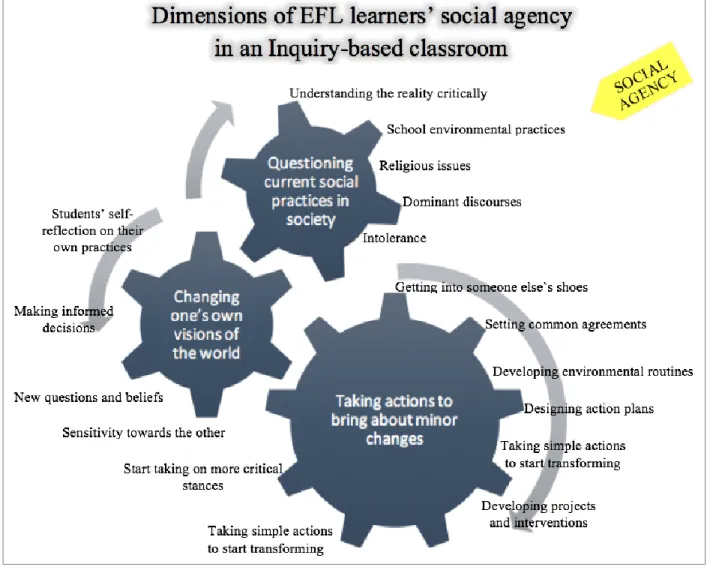

Dimensions of EFL learners’ social agency in an Inquiry-Based classroom ... 64

Questioning current social practices in society ... 65

Changing one’s own visions of the world... 74

Taking actions to bring about minor changes ... 80

Chapter 6 ... 87

Conclusions ... 87

Limitations ... 89

Pedagogical Implications ... 89

Future Pedagogical and Research Practice ... 90

List of Illustrations

Illustration 1 Co-relations of Critical Literacy Practices and Social Agency ... 25

Illustration 2 Adaptation of The Authoring Cycle Model ... 52

Illustration 3 Group 3, oral presentation. ... 56

Illustration 4 Group 2, third written report`s draft. ... 57

Illustration 5 Group 2, part of the final report. ... 58

Illustration 6 Emergent categories ... 64

List of Tables

Table 1 Research Questions and Objectives ... 16

Table 2 Learning Objectives ... 51

Table 3 Pedagogical Intervention Outline ... 53

List of Appendices

Appendix A Consent Form Model ... 99

Appendix B Interview Protocol ... 100

Appendix C Pedagogical Intervention Syllabus ... 101

Appendix D Lesson Plan: Reading the School ... 105

Introduction

“[…] all of us need to reflect critically on our own experiences and those others; then we need to connect new thoughts to our lives in new ways” (Wink, 2005).

From my view, being sensitive towards others, as well as towards the planet, society and

social practices around it represents one of the biggest challenges that youth as constructors of

the world are facing today, and education plays a critical role in this claim. In relation to this

Kaewnuch (2008) has asserted that “[…] education plays an important role in inquiring for

knowledge and in creating moral subjects for holding the society together” (p.11). Bearing this in

mind together with reflections upon my pedagogical practice and experiences and some literature

review, I become interested in examining the alternatives learners have to legitimize their voices

in the construction of their own life-worlds (e.g., Bautista & Parra, 2016; Behrman, 2006;

Contreras & Chapetón, 2016; Kaewnuch, 2008;Mendoza, 2010; Umbarila, 2010). Consequently,

the project, EFL Eleventh Graders’ Decision-Making via Critical Literacy Practices: A Study of

their Social Agency, was born.

I developed this research project as a study on learners’ social agency, with language as a

mediator, within the Master Programme in Applied Linguistics to TEFL at Distrital University in

Bogotá-Colombia, and chose Literacy Processes in Two Languages as the research area. Its

ultimate goal is to better understand the construction of a sense of social agency when students

are part of an Inquiry-based experience.

This thesis consists of six chapters. The first part contains the problem statement. I

describe the context in relation to English education and my experience as a teacher that has led

to my current position as a researcher and to pose the research question. Moreover, it explains

the importance of developing the study, as well as its objectives, as an attempt to add

The second chapter serves two purposes. It first proposes a theoretical discussion based

on Critical Pedagogy (Freire, 1994, 2002, 2005; Giroux, 2010; McLaren & Kincheloe, 2008;

Wink, 2005), and Socio-Constructivism (Dewey, 2001, 2004), that inform my thinking and

understanding of learner decision-making capacity and social agency. Second, this chapter also

reviews relevant research-based literature pertinent to my topic in order to situate my study in

scholarly discourse.

The other chapters provide a description of the research approach (Creswell, 2014;

Denzin & Lincoln, 2011) in interplay with the pedagogical intervention and data management

(Miles & Huberman, 1994) to build the environment within which I conducted the qualitative

study. In doing so, a fascinating trip through the interpretation of students’ declarations (Glaser

& Strauss, 1999; Gurdián, 2007) and the research question, having as a port of arrival the

literature review, brings up one main category and three correlated categories as a response.

Finally, in the last part, conclusions, research and pedagogical implications are depicted and aim

Chapter 1

Statement of the Problem

This chapter gives an overview of my research interest from the social, pedagogical and

personal perspective by placing it in a specific context where social agency is examined.

Therefore, the goal of this section is to state the problem, research question, and objectives.

During the pedagogical practice of my being an English language teacher and my taking

into account mainstream ELT methodologies and approaches like the language-centred methods

I am used to, the teacher-centred approach has been the prevailing tendency inside my teaching

and language understandings. In this tendency, in which the teacher is the crucial element of the

teaching-learning process and his/her fundamental task is through explanation most of the time,

it seems to me that students’ interests and voices need to be considered in the curriculum

(Kumaravadivelu, 2006).

As part of a diagnosis from my experience inside the private institution I work for, and

where the study took place as well as unstructured observations of my own classes for a period

of six weeks as a participant in this context, I reached a two-fold conclusion: First, I was

emphasizing the formal aspects of the language. I noticed that I focused more on accuracy and

fluency rather than on providing opportunities for learners to become involved in real

communicative events. There were few opportunities to engage in social practices that could

stimulate students to express themselves freely.

Second, with respect to the institution`s philosophy, it considers the importance of

preparing the students integrally with the purpose of building a better society (Institutional

Educational Project –PEI by its initials in Spanish, 2014); in the same sense, the English Area

Project-Based Learning [PBL]1, as one of the learning models. As stated here: “At the end of the term,

students work on the final project following the PBL approach. Further PBL information is

found in chapter 2” (Santa Mónica School, 2015, p. 56).

This drew my attention toward the need to foster students’ active, critical, and informed

participation concerning learning in today`s world.

Bearing in mind these outcomes, together with my interactions with various actors in the

field of education, including conversations with other English teachers and pupils from the

school [such as brief encounters and talks with professors in the Master Programme in Applied

Linguistics to TEFL]; I became increasingly concerned with teenagers’ social agency. As a

consequence of this, I considered the necessity of seeing adolescents as political and social

actors, as active beings whose agency is relevant in the construction of their world (Dewey,

2004; Freire, 1994, 2002; Giroux, 2010; Wells, 2005; Wink, 2005).

These insights led me also to review literature about language learning and critical

applied linguistics and I came to see language as a means for learners to discover meanings, to

grow and transform their world, to explore their deep feelings and emotions (Freire & Macedo,

1987; Pennycook, 2001).

Meanwhile, from the perspective of Critical Pedagogy [CP], which frames this

exploration, education has to attempt to be “progressive” as John Dewey (2004, first published in

1938) claims, not just to look at the student from Freire´s theory on banking education, where the teacher dominates the classroom and in the same way knowledge, only filling the student´s mind

with a lot of information. On the contrary, CP stands for seeing autonomy as part of a view of

education in which the student has the freedom to make her/his own choices.

In keeping with the presented ideas one wonders about the life issue, which would intend

to review teenagers’ agency, decision-making capacity and their voice construction related to

their school and world, as well as their learning process. Being more specific, inside the English

as a Foreign Language [EFL] setting youth cannot be labeled as mere language learners; by

contrast, teachers should think and understand them from a critical viewpoint, trying to unveil

connections between learners’ agency and surrounding social matters, as well as knowledge

construction. Consequently, there is a need to motivate and engage students in more active and

challenging real-world issues and learning practices.

At this point, a question came to light, and objectives set to possibly tackle this

problematic panorama.

Research Question and Objectives

In relation to the proposed phenomenon, the addressed research question is related to how

teenagers make sense of their social agency while they become actors and authors of small-scale

inquiry projects, and the main goal of the study is to capitalize to some extent on eleventh

graders’ informed decisions that show themselves as active agents inside the school as shown in

the table below:

Table 1 Research Questions and Objectives

Research question

What does eleventh graders’ Authoring Cycle in an EFL classroom reveal about their social agency?

The research objectives

To better understand eleventh graders’ decision-making capacity and what characterizes it concerning social issues that emerge in their daily school experiences by means of L2 as a mediator.

Rationale

Within the previously described research focus there was an inquiry that dealt with the

theme of learners’ decision-making capacity inasmuch as this project showed that learners’

agency and their choice-making ability are important constructs that reveal learners’ social

agency towards their context, particularly as concerns their perception of matters inside their

school. This line of thought addressed the contribution of theory and thinking in teaching and

learning language, deriving from the concept of language as a social practice integrated to CP.

The direct impact on the students was that they developed their inquiry skills as they took

part in The Authoring Cycle [AC see chapter 4]. Additionally, students became aware of their social agency sense and how they dealt with different circumstances they were involved in

during the pursuit of their aims and how these aims changed as they went into another inquiry

cycle [see Data Analysis chapter].

Linkages between students and their school were fostered by understanding how their

school was organized, how people at school interact, or what situations students face on a daily

basis, and also what it is beyond the quotidian relationship with their teachers and their

classmates inside their classroom too. During their process inside the AC, they began to see

themselves as part of their school problems and felt the necessity to voice themselves in regard to

what they were living, uncovering and dealing with, not only toward school issues, but their

society too.

With regard to the setting where this work took place and as it arose from a diagnosis that

portrayed an inconsistency inside the institution [as well as considering the presented ideas on

page 14], it was possible to say that there was a mismatch between the school´s philosophy, and

the real pedagogical practices inside the EFL classroom. Therefore, the study was worth doing

say or to do regarding their society.

Furthermore, students had opportunities to practice language skills by approaching social

dimension, as they were seen as actors inside the socio-cultural setting they are involved in. As a

result, the English Area discovered different insights, first to see students as social actors and

second to understand the relationship among PBL as part of an Inquiry-based pedagogy, critical literacy practices and EFL methodologies, and finally to see The Authoring Cycle as a

meaningful model to work on projects and language learning itself. Consequently, it contributed

to their pedagogical and professional development which in turn was relevant for the school

itself inasmuch as the English Area policies and the school´s philosophy seemed increasingly

like the real EFL classroom practices.

As an English language teacher, I learnt the need to incorporate the view of language as

playing a major role in the construction of difference; hence, from the classroom social issues

can be addressed by means of it. As Pennycook (2001) has pointed out, one has language as a

social practice that emerges to give evidence of people`s life experiences within specific

contexts, beliefs about language learning, as well as helping them to get a better understanding of

educational practices in a broader social realm, for instance, resistance, power, dominant

discourse, emancipation, and genre among others.

Finally, by addressing CP I was able to transform my view and role as Language teacher

into an agent of change, being aware of all the possibilities I have to act within the educational

context in favour of society.

Background to the Study

To locate my study and give more grounds to the research problem it is necessary to

present a revision of the literature from local and global research-based sources relevant to

teenagers’ social agency, which has been an object of research in the field of education around

correlated with the field of English as a second and foreign language education and social

interaction; and then, social agency seen through the lens of critical pedagogy. Some of the

theory and research-based sources included in this section are further addressed in the literature

review chapter.

Some studies about learners’ agency: Extensive research has been undertaken in

supporting children’s and teenagers’ agency, embracing language education and social

interaction. Thereby, in this part I will remark on some of the ones which act as a bridge to

learners’ social agency.

The following studies show agency as the capacity learners as human beings have to

shape their experiences and life trajectories in order to improve life situations (Bandura, 2006).

For instance, Aro (2009) maintains that children develop their agency over the years, taking into

account their language learning process, since learners give evidence related to the way they

conceptualize learning and utilize English through three aspects which are interconnected by

themselves, content, voice and agency. Therefore, this longitudinal case study with primary

school students found that agency became progressively stronger; “learners’ voices and agency

got richer and more diverse: they changed and developed in more dimensions than just the one”

(p.156).

Dealing with human agency and good language learning i.e. and how to be a good learner

and become successful in Second Language Acquisition [SLA] have also been studied. Norton

and Toohey (2001) make clear how well SLA learners’ access to language learning tasks differ

from poor learners’ and what characteristics of learners predisposed them to good or poor

learning. Most SLA good learners make use of human agency to get in contact with the social

networks of their communities. These scholars state that instead of paying attention to the

their discourses and building up their identities in terms of social interaction inside their

communities.

In a different approach, distinct scholars and research (Frederick, 2012; Lee, 2011; Li,

2006; Mashford & Church, 2010; Mick, 2011; Miller, 2010) give an account of agency as a

practical way to construct identity, and the possibilities children and teenagers count on to make

decisions and position themselves as agents through explicit attention to language use, in some

cases informed by the view of education as a practice to be negotiated within restrictive contexts

(Freire, 2002).

Li (2006) and Miller (2010) draw on the concepts of language, identity, and agency in

terms of SLA. These research studies were conducted on the basis of understanding identity

since the essential self´s expressions are directly linked to the learner`s environment, who counts

on human agency and is able to commit toward the intercultural context with the purpose of

taking advantage of it and fostering language acquisition; so, as a result there is evidence of the

positioning of individual’s and learner´s identity.

Moreover, the idea in which individuals appropriate themselves of human agency and

cultural context when acquiring a language is also supported by Lee (2011), who argues that the

findings of his investigations show evidence related to how Taiwanese college EFL students’

investment in English learning was shaped by their life stories, their preferences and their beliefs

about the future. Also outlined is what is needed to gain a more precise understanding of what

counted and contributed to learners’ agentic actions inside and outside the English classroom.

The learners’ agency is constituted as a dynamic process as regards social interaction too.

In this view, for instance, Mashford & Church (2011), using conversation analysis in their

research, have demonstrated how early childhood teachers can foster their students gaining

agency when peer disputing occurs by giving children the responsibility to solve their disputes

social practices. Along with this perspective, Mick (2011) demonstrates how children’s

capability contributes to their subjectification as social beings and how to co-design the

educational institution they are in, as well as providing the discourse on differences regarding

economic status; subsequently, through these kinds of social practices, children’s agency plays a

part due to their desire of shaping their surrounding context via the negotiation with teachers.

Following this track, Fredrick (2012) argues that students use language as an excuse to

traverse the social space they find in the classroom in terms of their teacher´s position and power

by generating their own linguistic tools to communicate with each other, avoiding teacher´s

restrictions toward social interaction. In this sense, one has communicative competences in

specific social practice during classes, which reveals how students´ agency do sophisticated

linguistic work. This author also suggests that agentic learners have the ability to learn what the

school does not want them to learn, due to social interaction in school settings. They enact

specific linguistics tools, whose meanings are only understood by the creator-participants, as

these occur in another context.

To sum up at this point, and taking into consideration the above research studies to

approach antecedents as regards my interest in learners’ agency, it is very clear how identity,

human agency, learning agency and social interaction are fostered by means of language;

likewise, learner agency and identities play a meaningful role inside and outside the classroom.

What has been done in relation to social agency: The main construct of this research

study deals directly with social agency, which has been a concern broadly investigated

worldwide. Although not many studies focusing specifically on learners’ social agency have

been developed in Colombia, some of the following studies have focused on teachers’ social

agency and education as a means to empower it, while others address learners’ social agency

Kraft (2007), based on his ethnographic study, reports the construction of a school-wide

model of teaching for social justice consisting of three central components: the integration of

issues of social justice across the curriculum, the use of socially just teaching practices, and the

creation of a socially just school community, which in turn were applied in two public middle

schools. Findings clamor for progressive educators to adopt practical, practitioner-oriented

models of schooling in order to more effectively advocate for a school reform that really shows

caring for society.

This focus on the potential of education is paralleled in Ball’s (2000) work on how

teachers inside community-based organizations in an African-American context are able to

challenge learners “to consider alternative life possibilities, to become critical thinkers, and to

consider transformation of their current life situations and the life situations of others” (p. 1006).

This research was done in three classrooms and had the purpose of imparting the knowledge and

skills needed to get and keep a job; the discourses given were based on the CP premise that

maintains that pedagogical practices facilitate or encourage human action and social agency.

In the same direction, different scholars in Colombia (Clavijo, Guerrero, Torres, Ramírez

& Torres, 2004; Quintero & Guerrero, 2010; Samacá, 2012) throughout their research and

theoretical articles discuss the myriad possibilities education has to become the keystone of a

better society.

For instance, Clavijo et al. (2004), on their interpretative qualitative in research study to

identify the processes of innovation in the language curriculum by a group of public school

teachers in Bogotá, evidenced that teachers planned and carried out innovative pedagogical and

curricular practices, thinking critically about students' needs, interests and learning process

advancement. Furthermore, during the same process they adjusted their classroom projects with

Along the same lines, Quintero & Guerrero (2010) display their findings in terms of the

necessity of inviting English teachers around the world to adopt a critical perspective in their

educational endeavour. They clamour for a transformation of the education of pre-service

teachers’ concept by acquiring a critical-reflexive vision that will bring together an active

position (Freire, 2005; McLaren & Kincheloe, 2008; Wink, 2005). This paper reports the

practical implementation of their statements by means of the proposal and development of two

innovative pedagogical projects in Bogotá, Colombia.

On her part, Samacá (2012) reflects on the language teacher preparation programs, and

how they provide a new opportunity for pre-service teachers to re-think their pedagogical

experiences for social transformation, arguing that critical pedagogy as a philosophy of life

empowers teachers to achieve a better understanding of what teaching really entails and in

raising awareness fosters conscientization regarding their practices in educational settings.

The studies summarized before dealt with education as a big tool to engage learners in

lifelong learnings, which implies enabling them to capitalize on their capacity to analyse their

surrounding reality and step by step start taking a position and acting (Dewey, 2004; Giroux,

2010; Wink, 2005). Yet, other researchers have focused on the way youth are able to transform

the world by being political and social actors.

Mirón & Lauria (1998), in a comparative case study of two inner-city high schools

located in the United States with high admissions standards, described how a racially and

ethnically diverse population of students became both a means of resistance and accommodation

as regards a specific social situation inside their school communities: white hegemony. The

voices of these students show how they shape the sense of self, as well as their lived cultural

experiences, positioning themselves as agents who pose their resistance.

Just as Mirón & Lauria, Sherif (2016) reports theoretical and practical findings from a

programme. It is a dynamic school system that remarks on learners’ actions taken to improve the

self, family, and community. The findings from this study legitimize students’ voices as to how

they perceive themselves as agents of personal, family, and community change.

To conclude, in this section I reported several studies that displayed results in the main

construct of my research study. Hence, my investigation contributes to the specific issue of

Chapter 2

Literature Review

What is the relationship between literacy practices and social agency enacted inside the

school? From this standpoint, this chapter presents the concepts of Learner Informed

Decision-Making and Learner Social Agency that I expect to construct after a discussion. This will be a

dialogue between students who make their own informed decisions and are characterized as

social agents and Literacy development as a practical realization of agency, having as a special

guest the EFL classroom as a socio-cultural context.

The core of the aforementioned discussion will be based on some tenets from the

perspective of Progressive Education (Dewey, 2001, 2004), Critical Pedagogy (Freire, 1994, 2002, 2005; Giroux, 2010; McLaren & Kincheloe, 2008; Wink, 2005), and Critical Literacy

Practices (Freire & Macedo, 1987; Luke, 2012; Shor, 1999; Wells, 2005) as the main focus. For

their part, Ahearn (2001), Bandura (1986, 2006), and Ballet, Biggeri & Comin (2011) intervene

in the dialogue, contributing to my social and critical perspective.

The following visual display illustrates the interaction among the actors of this dialogue:

Students who make their own informed decisions are characterized as social agents

An important point I want to make here is the connection between Bandura and Freire for

the discussion of human beings as subjects who exercise personal agency (Bandura, 2006) and

human beings as active agents, not being mere objects [passive recipients] who exercise personal

agency aiming at making this world a better place (Freire, 2002). This connection states my

preliminary view of agency: reflection and action are interwoven.

Under this light, I bring into play two scholars. On the one hand, from the Social

Cognitive Theory, human agency is “the human capability to exert influence over one’s

functioning and the course of events by one’s actions” (Bandura, 1986, p. 8). In this sense, it

refers to the capacity human beings have to think, evaluate and examine different paths of action

to improve life circumstances and override future events or conditions over which individuals do

not have control in order to shape life situations. This concept is also supported by this

psychologist years later, to wit: “people are contributors to their life circumstances, not just

products of them” (2006, p.164).

On the other hand, Ahearn (2001), a linguistic anthropologist, paints in an insightful

essay a far more complex picture of agency considering two fields of scholarship which are

interwoven: sociocultural and linguistics. She says that the manner with which people create

actions and thoughts into the social structure they are immersed in provides evidence as to

human beings as agents. “Agency refers to the socioculturally mediated capacity to act” (p. 112);

by doing so, individuals as situated participants take part in the social construction of knowledge

and the constitution of their environment. It relates to the social dimension of this study.

Regarding the linguistic field, Ahearn draws one’s attention toward the meaning of the

relationship among language, linguistic practices and sociocultural environments. Based on the

research and theoretical frameworks she analyzes; this scholar refers to agency and language as

realities by means of language. For addressing this very issue, areas of literacy practices,

language and genre, learning, and language learning itself are mentioned.

Following the foregoing considerations (Bandura, 1986, 2006; Ahearn, 2001) and to

tackle the core of this study, CP articulates the concept of agency as Freire (2002, first published

in 1970) maintains “Human beings are not built in silence, but in word, in work, in

action-reflection. But while to say the true word—which is work, which is praxis—is to transform the

world…” (p. 88); “to transform the world” through the lens of CP implies being committed to

the humanization of the reality we are living.

Bearing in mind the previous background on the concept of agency and my

understandings, I am now going to address the issue of students’ agency. Ballet et al. (2011)

refer to it as “Seeing children and young people as subjects of capabilities means that we can

consider them endowed with agency and autonomy, able to express their points of view, values

and priorities” (p. 22). Children and adolescents play an important role not only in their families,

but also in different contexts they are immersed in such as school, sport clubs or some society

activity, and they take advantage of their choice-making capacity as little aspects affect their

daily routine as they try to get their freedom somehow in terms of their parents’ guidance. As the

authors claim, “It is much more about understanding how children can be seen as autonomous

beings searching for agency, as adults do” (p. 27).

In this view and revising among the set of principles provided by socio-constructivism,

one of them draws attention to the relationship among the construction of knowledge,

personalities, language learning and the role of society (Dewey, 2004). Which at the same time

accounts for the CP tenet that states how the human being reflects upon the reality and the

environment he/she is living in and makes choices and meanings in order to tackle them; there is

a call to action (Freire, 2002) which is from the CP viewpoint agency itself. Therefore, it can be

For instance, Forbes (2008) carried out a study as to how preteens give meaning to their

experiences in the context of restrictive language policies [in a bilingual school in a U.S.-

Mexico border zone with an institutional structure of the transitional bilingual program]. The

findings of this dissertation highlight how these learners position themselves as agents through

explicit attention to the benefits of the language use by being aware of their ability to negotiate

within restrictive environments.

One point to make here is that teenagers’ surroundings are made up of the educational

and family settings as well as others in their everyday living; and one realizes that students`

beliefs, experiences, ideas, determinations and actions take place in these contexts of quotidian

social practices such as schools, within schools, and language classrooms. It allows me to say

that somehow or other teenagers are able to give sense to their inquiries, decisions and the way

they position themselves by means of their actions or attitudes toward the circumstances they are

involved in. Distinct research studies (e.g., Chapetón, 2005; Crawley, 2010; Forbes, 2008;

Kaewnuch, 2008; Rincón & Clavijo, 2016) that are addressed at some point during this

discussion give an account of it.

Freire (1994) states learning is a social practice in which the school takes advantage of

the students’ choices, and the process in which they make own perceptions and understandings.

This author also notes, “I cannot understand human beings as simply living” (p. 97), which

means human beings are certainly not passive recipients, they are agents. As a consequence,

learners make their own choices in the context of their daily routines, their culture, their own

personal life histories, as well as based on the circumstances they are facing, opinions or advice

from people around them, or just by using their perception of life, their judgments of what they

see in society by means of the media, their peers, families, etc.

The EFL classroom is a socio-cultural context that allows agency to reveal itself. In

observe that informed decisions [a concept I will explain further] were made on the basis of

experiences and interpretation of the information learners were exposed to inside their specific

environments. Likewise, the role of the teacher is challenging pupils to unveil opportunities for

hope; and as a result, new questions, beliefs and worldviews arise. This reflection outlines the

Freirean (2002, 2005) idea of conscientization.

Conscientization as one of the tenets of CP accounts for the decision-making capacity as

long as there is a transformation in the way of perceiving the world. For instance, on the one

hand, Kaewnuch (2008) and Rincón & Clavijo (2016) move away from the traditional way of

teaching in terms of SLA, and draw on literacy skills by exploring social and cultural issues.

Their research studies were conducted on the basis of understanding education as a medium to

help students grow up as active subjects who will be part of the social power that helps society:

“My ultimate aim of teaching Thai EFL writing is to prepare students for the society, not for the

workforce but for maintaining and developing the society together” (Kaewnuch, 2008, p. 57).

Even data collection sources and procedures may vary; outcomes of these investigations

observe that participants´ voices reveal how they decide to make meanings of their own

experiences, how they clarify problematic issues inside the context they are embedded in, and

project themselves as being intellectual, growing morally and obtaining values, and obviously

gaining a good economic and social status in order to improve their society’s conditions. As

Rincón & Clavijo note, “Exploring social and cultural issues through community inquiries

provided students with foundations to think critically about their role in the community” (p. 80).

On the other hand, in a non-formal education environment, Chapetón (2005) by means of

her qualitative case study with 18 adults in situations of displacement, victims of illegal armed

organizations in Colombia; implemented a reading club as a literacy practice attempting to build

their social reality. As a community, they identified adversity factors, resilience-building in

terms of strong family bonds, networking, and learning from their experiences; choosing to

become themselves in subjects of their reality. As it is stated in the data analysis “participants

were empowered to illuminate the conditions in which they live[d], to help each other as a

community, [and] to overcome those conditions” (Chapetón, 2005, p. 308).

Across the decision-making domain, theory and research have shown the complexity of

this human capacity. For example, the comprehensive model (Anderson, 1983; Nutt, 1976, 1984;

cited in Eisenhardt & Zbaracki, 1992) describes decision-making process as follows: “[…] actors

enter decision situations with known objectives. These objectives determine the value of the

possible consequences of an action. The actors gather appropriate information, and develop a set

of alternative actions, they then select the optimal alternative” (p. 18). In CP terms, when an

individual gathers the suitable information and reflects critically upon its various aspects, this is

known as problem-posing (Freire, 2002). Thus, I believe problem-posing can be linked to this description of decision-making due to the fact that to deal with a situation, made choices and

decisions are closely interwoven with reflection and introspections concerning various

alternatives and data.

Furthermore, this model assumes the social and cultural environment as a crucial factor

inside this process; for instance, when individuals consider limitations, people around, or choice

alternatives inside the context, “the complexity of the problem and the conflict among the

decision makers often influence the shape of the decision path” (Eisenhardt & Zbaracki, 1992, p.

22). Then there is rationing according to cognitive development, aiming at avoiding risks and

overcoming obstacles. Both intuitive and informed decisions are the result of this broader range

of elements combination (Forbes, 2008; Chapetón, 2005).

From another perspective, according to Gardner & Herman (1991), adolescents

preference and perception due to the manner they gather and use the information in analyzing

alternative options and defining cost-benefit, but the young tend to adopt a risky behavior more

than adults, and (3) temporal perspective; this approach assumes that teenagers have a tendency

to focus more on immediate rather than long-term consequences.

In the EFL field regarding decision-making process per se, Quintero (2011) maintains

that “Decision-making needs to be the result of a meaningful process that considers purpose,

information collection and information interpretation. This process provides our beliefs and

common sense with foundations to make decisions” (p. 133). He carried out an investigation

based on informed decision-making as a sound practice inside the evaluation process in the

English Language Teaching [ELT] curriculum, and proposes a more humane and less technical

approach to evaluation, based on the reflections and conclusions of the participants [in-service

teachers] who developed small-scale projects framed in the evaluation process.

Based on the revision of the research-based as well as the theory-based literature in the

domains of agency and decision-making, I consider that learners are capable of coming to their

own understandings in an informed way, sometimes but not always thanks to schools.

In relation to this, Crawley (2010) based on his investigations on human agency with

children and teenagers in the UK asylum system, states that no one gives those teenagers a

chance to say what they are thinking and that it is necessary to find space for children's agency in

this system. Since children and adolescents are social actors and active beings whose agency is

relevant in the construction of their lives as well as their world, the necessity of listening to

children`s voices in the UK asylum system is evident due to the fact that they are not passive

victims of adult violence. This ethnography study was developed with 27 children and youths

from a British asylum and brings together a number of narratives and memories by means of

interviews; also, the investigator could do a deep observation of the social context. Most of the

upon via adult explanations and rationalizations, and at the same time these wrong concepts do

not allow them to fully develop their identity and human agency.

The part of the conclusion of this study which draws my attention was that children and

youth in this kind of situations have a lot to say about their world and experiences; the

interpretation of their voices in this place, which is not a formal academic institution, deals with

the meaning of agency based on informed decisions from their experiences and their search

toward being social and political actors. Under this argument, it is worthwhile relating it to two

principles of CP: First, praxis, which means action and reflection and whose relationship validates and gives power to the word; and second, conscientization as the key process of

becoming a subject with other oppressed subjects, or developing a critical awareness of reality

based on everyday experiences (Freire, 2005, first published in 1969).

In light of the above, when agency is enacted, there is a previous decision-making

process, which is sometimes intuitive, other times informed. Additionally, those informed

decisions are made bearing in mind assumptions, experiences, gathered and interpreted

information, good or common sense and contexts, and therefore the others and society: Then, the

way the individual sees the world is through reshaping and reflection; and inquiries,

determinations and actions re-emerge to transform the world.

Thus, the above considerations frame my concepts of learners’ decision-making within

the frame of CP. I can state that learners` social agency appears as a way to account for the

potential they have to reshape perceptions of their realities and tackle social issues.

Consequently, I am able to propose my own definition of social agency for this study, addressed

from a decision-making capacity. Social Agency is a human capacity, related to the

decision-making process, which goes from self-reflection and worldview-changing to action-taking,

In agreement with the previous statements, investigators have sought to demonstrate that

students who make their own informed decisions are characterized as social agents. For instance,

on the one hand, Fehrman & Schutz (2011) and Jones (2017) draw on social action programs

which high school students are involved in. Their research studies were conducted on the basis of

grasping these community engagement projects as pedagogical platforms where students make

meaning of those experiences, legitimizing themselves as agents of social change.

Jones included a quantitative survey and interpretive interviews that were used to

explicate not only participants’ voices as to their experiences in the program PeaceJam

programming [movement in peace education and community service], but to make a descriptive

and inferential analysis relating life purpose, academic engagement, and community orientation.

One of his findings that served the objectives of my study was regarding the percentage of

students who were willing to include this kind of activities as a new habit, (Eisenhardt &

Zbaracki, 1992; Quintero, 2011) “Almost half of PeaceJammers (45%) shared that they already

plan to continue community service in the future.” (Jones, 2017, p. 62), providing evidence of

how they reshaped their outlook of the world “[…] a different view of “the bigger picture” or

gaining experience in new topics or ways of thinking. Perceptions included the global “It’s

changed my point of view about everything; life and in general” (p. 56).

The conclusions of these studies report an account of adolescents’ paths of actions. They

were engaged in promoting social justice and local community transformation, building a broad

range of skills and habits, and linking this experience to a personal call to action.

On the other hand, qualitative research undertook in the Colombian context about

students’ perceptions of social concerns allowed me to broaden my perspective with regard to

students as decision makers inside the EFL classroom. The following research works were made

on the basis of experiences and interpretation of the information learners were exposed to inside

works of art can have an impact on tenth graders’ viewpoints of reality. Data analysis caused

these researchers to maintain that social transformation starts by being aware of real-life

problems. As participants made sense of situations, interpreted and shared thoughts among their

peers (Gardner & Herman, 1991), doing so led them to a new world vision about the situations

around them.

Meanwhile Umbarila (2010) makes an attempt to promote social reflection and cultural

recognition by enrolling the participants [ninth graders] in critical pedagogy practices. Students

were exposed to authentic historical facts, then discussions, reflections and their analyses of the

situations connected to their reality empowered their voices to refuse and denounce social

concerns such as racism, dominant cultures, imperialism and civil resistance movements.

Therefore, one sees that these dialogical transactions enable them to define themselves as social

and cultural subjects. What should be noted from the results is the construction of the Voices of

Responsibility and Commitment with the Other among the students.

These authors highlight the idea of learners being able to make their own decisions and

postures thanks to the school; however, Bautista & Parra (2016) and Umbarila (2010) emphasize

the development of the learners’ new insights as regards the world around them and taking

stands or opinions toward any life issue; undoubtedly, adopting a position implies expressing an

agent-like action too. Additionally, Fehrman & Schutz (2011) and Jones (2017) suggest that

learners who have been enrolled in social service programs develop their inner strength in the

construction of themselves as subjects of social change.

Taken together the aforementioned research studies, I assert that students who make their

own decisions are characterized as social agents that shape or reshape their surrounding

environment, helped or not by schooling. Notwithstanding, this review led me to assume that

education is a powerful resource that creates favorable circumstances in the search of social

human beings with their role inside the society. On the other hand, it acknowledges education as

a strong force to take advantage of human agency and at the same time to foster it in order to

have learners rethink, take postures and act upon their own lives, but also focus on the real

scenarios they are part of.

Conducted on the basis of the previous discussions, Dewey (2004) and Freire (2002) are

two remarkable scholars who, from a socio-political vision, highlight the role of education in the

transformation of society. Freire maintains that through problem-posing education [a concept

that is paralleled in Dewey’s ideas on progressive education, as well as in Short (2001) and

Wells (1995) approach to inquiry-based curriculum] and placing learners at the core of the

curriculum, they question the surrounding problematic issues, make sense of the manner in which

they perceive the world, and develop a critical consciousness as a handful of studies have

demonstrated (Bautista & Parra, 2016; Crawley, 2010; Forbes, 2008; Kaewnuch, 2008; Rincón

& Clavijo; 2016; Umbarila, 2010).

Furthermore, many investigations (Fehrman & Schutz, 2011; Forbes, 2008; Jones, 2017;

Kaewnuch, 2008) provide evidence that adolescents are competent decision makers whether

making informed choices (Eisenhardt & Zbaracki, 1992; Quintero, 2011) or considering peers’

or adults’ influence and taking risks (Gardner & Herman, 1991). Consequently, students are able

to improve their life conditions and take necessary actions to build a more just and equitable

society (Chapetón, 2005; Fehrman & Schutz, 2011; Forbes, 2008; Jones, 2017). In this vein,

informed decisions and social agency actions cannot be isolated.

Nevertheless, seen from another angle, distinct studies examine adolescents and adults'

understanding of social concerns, but do not include formal educational settings (Ballet et al.,

2011; Chapetón, 2005; Crawley, 2010). Though, others deal with agency inside the EFL

classroom (Bautista & Parra, 2016; Kaewnuch, 2008; Rincón & Clavijo, 2016; Umbarila, 2010).

classroom as a suitable atmosphere for students to reflect upon their lives, sociocultural contexts

and particularly make choices and determinations, using L2 as a means.

In the line with the preceding ideas, education must be understood as a political action

looking forward to the awake of the individuals from their oppression and to generate social

transformative actions. In this regard, CP does an interesting analysis upon the political nature of

the education, as well as the educator´s role as the communication facilitator. As Giroux (2010)

a leading writer of CP, claims “It is the task of educating students to become critical agents who

actively question and negotiate the relationships between theory and practice, critical analysis

and common sense and learning and social change” (p.717). This idea provides evidence of my

own concept of social agency seen through the eyes of education.

From my viewpoint, and bearing in mind that Freire (2002, 2005) claims to develop a

critical social awareness among students, to humanize more and more learners, but also teachers,

and to encourage them to comprehend and transform their reality; regards with those situations

of justice, democracy, power, inequalities and dominant discourses, environmental conscience,

and all of those particular circumstances in which other’s lives are being affected by someone

thoughts and actions. I think education emerges as the only vehicle to construct a more human

and fairer society.

Literacy development as a practical realization of agency

Albeit, my previous my stances of Decision-Making and Social Agency, now I am going to concentrate on Critical Literacy Development [CLD], attending to make it plays with these concepts in this research study.

Classroom social practices are enacted by language as a means, as a result, language is a

social practice itself, and learning taking advantage of it, is rebuilt day-to-day in the social

relationships, give meanings to their life stories and games or make judgements during classroom

or school activities. I do agree with Freire & Macedo’s (1987) statements “Reading the world

always precedes reading the word, and reading the word implies continually reading the world”

(p.35). Now, in this light, Shor (1999) acknowledges that “literacy is understood as social action

through language use that develops us as agents inside a larger culture” (p.3). This process

entails human beings to go beyond signs, to develop the power to see, read, write and rewrite the

world around them, and as language is everywhere, it is a social practice that enables individuals

to do it.

Street (2003), is another leading theoretician that has been focusing on New Literacy

Studies, and due to this nature, his articles are an excellent source of data related to ethnographic

studies of the several kinds of literacies involved across environments. He addresses thinking

about literacy not as the mere exercises of reading and writing but as a social practice. As

literacy is embedded in social practices, and the outcomes in the learning process will depend on

the particular context the learner is situated in, Street also revises the implications on education,

arguing the responsibility school has regarding the new perspective of literacy, and its

significance inside classrooms. Hence, he asserts, “The effects of these critical engagements

with social theory, educational applications and policy is that New Literacy Studies is now going

through a productive period of intense debate” (p. 87).

To gain a deeper understanding on Critical Literacy [CL], which comes from CP

principles, I propose an article written by Luke (2012), which tends to align Freire’s conceptions

and ideas, CL and discourse analysis in the sense of the necessity to face dominant discourses.

As this theorist points out, “[…] it [critical literacy] melds social, political and cultural debate

and discussion with the analysis of how texts and discourses work, where, with what

consequences, and in whose interests” (p. 3). This argument guides me into the reflection

the reader, and paraphrasing Shor (1999) and Wells (2005): Literature needs to be part of the

construction of the self, and CL is a social practice itself that involves human beings on

expanding their minds to go beyond the texts, growing in understanding and valuing other

cultures and language, challenging social practices and everyday issues portrayed in literacy

practices.

From another viewpoint, CL and CLD deal just with young learners’ beliefs, opinions

and perceptions by means of the games enacted at school. Quintero (1997, as cited in McLaren &

Kincheloe, 2008, p. 277) argues that CP and CL let students with different background and social

contexts tell their own stories due to the fact that through their games, which can be within

narrative, artistic or literary contexts, children are able to provide data about their life

expectations and the way they see the world (Ballet et al., 2011). Consequently, CP gives pupils

the opportunity to express their own opinions and visions of the world.

These views (Freire & Macedo, 1987; Luke, 2012; Shor, 1999; Street, 2003) account for

CL understood as the literacy process inside education, aimed not only to integrate learners’

concerns, experiences, beliefs and context into the school´s practices, but also to make them

aware or their history inside the society they are living in. Indeed, being guided on this approach,

I do believe that CLD is a practical realization of the language as a vehicle, and that social

agency appears as a resource to capitalize on the potential that learners have to tackle social

issues through their literacy practices.

The following studies I describe are relevant to my line of thought on this topic because

they involve a critical view of CL practices as well as the social agency inside them:

Maguire & Graves (2001) carried out an investigation named “multilingual children’s

speaking personalities” and their understanding of daily interactions with others in specific

environments was studied. They applied close observation of three Muslim girls’ patterns of

insights related to what the relationship between L2 writing and identity construction, the

writer´s voice, agency and reflexivity is. In this inquiry with young L2 writers, they were able to

see how these learners when exercising writing, first, developed a high degree of control over

sentence- and discourse-level aspects of English; and second, it provided young writers with

chances to communicate their ideas, relate school experiences and thoughts, voice their opinions,

and represent themselves to others. They indicate how by means of literacy practices preteens

construct their identity and position themselves socially as well as recognizing what is significant

and negotiated in different social situations.

In the local context Contreras & Chapetón (2016) assert that “language is viewed as a

social practice where teachers encourage social awareness and promote spaces for interaction

and critical reflection” (p. 143). Their investigation with seventh graders in a public school in

Bogotá, Colombia, seeks to promote peer interaction by using cooperative learning principles,

providing opportunities for dialogue, collaboration and reflection while addressing social aspects

of their school lives by means of CL practices. The results report that this experience advocates

changes in classroom social practices and, at the same time, promotes personal growth and social

awareness among participants.

Qualitative action research developed by Contreras, A. (2016) and Pérez (2013) in two

other public institutions addresses conflict resolution and verbal and physical aggression among

EFL secondary school students by means of CL, as being the key component of the pedagogical

intervention. This led these teachers-researchers to reveal students’ understandings of the

relevant causes of conflict like students’ lack of social skills and parental care, as well as

bullying. Likewise, I highlight their reflections about the consequences of anger when dealing

with social conflicts, and their will to develop conflict resolution. “[…] inquiry along with

writing about social issues in English allowed students to develop rationality and sensitivity

From a different angle, Behrman (2006) identified by means of his documentary analysis,

which includes articles published between 1999 and 2003 concerning CL, how everyday life is

explored when reading texts on the same topic written from diverse points of view; as a manner

of unveiling messages and thinking about different perspectives and then researching social

problems, talking about them and adopting a stance through the authoring of one’s own texts. “In

this sense, reading and writing are not merely communicative acts but part of the habits, customs,

and behaviours that shape social relations and realities” (p. 487). This quote shows how CL

capitalizes on student’s social agency, portraying the conscious process present at the time of

reading and writing the word and the world (Freire & Macedo, 1987).

In this line, another outstanding analysis was done by Mendoza (2010). Thinking of

young Latinos growing up in poverty in the United States who need to deconstruct their

internalized sense of worthlessness and oppression, this researcher collected and evaluated an

assortment of children’s literature in Spanish. This pre-service teacher creates a CL curriculum

resource for bilingual educators so that dialogue and reflection with regard to situations of social,

economic and political injustice and inequities could be fostered. This framework reflects the

role play of CL as an attempt to inform and empower students to transformation (Shor, 1999).

Although the cited authors highlight the relationship between CL and social agency,

Contreras & Chapetón (2016) and Maguire & Graves (2001) reflect on the learners’ text, voices

and introspections inside a particular sociolinguistic-cultural environment. Among their findings

is the declaration that when working on reading and writing activities, the expression of the

identity, peer-interaction and social awareness is constructed taking into consideration life at

school; at the same time, students are able to make connections between their realities around the

school in order to better their literacy practices.

In a different way, Behrman (2006) explores in his documentary investigation how

projects, permitted pupils to take social action as a way of being in society. On her part Mendoza

(2010) provides an annotated bibliography for teachers as a tool for bettering CL while

Contreras, A. (2016) and Pérez (2013) reveal the way in which EFL students deal with conflict

resolution when inquiring and developing literacy skills about social happenings in their

community settings.

Concerning a description of how children’s and teenagers’ agency is voiced in CL

practices at EFL settings, my point of view regarding the link between CL and social agency is

that as human beings our literacy practices cause us to express ourselves in a conscious way with

regard to our surrounding world, and inquiry about social situations affecting our society and

realities as well. From a lesser to a bigger impact, we are active agents contributing to the

transformation of our sociocultural context. Education takes advantage of CL in order to face

social issues by reading and writing the world and the word (Freire & Macedo, 1987) and

strengthens people´s capacity of acting upon the reality.

From my perspective, the connection between social issues and language is better

explained from Freire`s expression “read the word” as the way people see, understand, and

interpret their contexts situated in the world; and at the same time take action upon their reality

with the purpose of transforming it. Using CLD and making language learners’ decision-making

capacity to develop academic literacy, students inspire themselves as co-authors of their own

texts. This process is made in a conscious manner, because of the critical perception, stances and

opinions learners express about their culture and their own experiences. This is a way of making

their voices heard, transforming the world by means of the word.

The link among the main constructs in this research study paints a far more complex

picture of my concept of social agency. Furthermore, considering the theory and research–based

literature provided above, one can say it is possible to assert that there exists a social agency`s

has to do with reading the outside world, where CL is a key tool that allows them to develop

critical thinking and a social awareness about situated surroundings; hence, making informed

decisions with respect to different social issues. As such, one can see decision-making is

complex to observe by CLD students exploiting the opportunities to raise their voices, report

their decisions and express their perceptions, viewpoints and positions regarding surrounding

socio-cultural settings, as well as society in general. The final part of the cycle I proposed is

taking action based on the two previous steps, seeking to reconstruct students’ realities, and

attempt to shape and reshape their sociocultural context; transforming into real change agents

Chapter 3

Research Design

This chapter presents the research framework -- i.e. the research approach of the study,

the setting in which it was developed as well as the participants, data collection instruments,

procedures and finally, the role of the researcher and ethical issues -- of this interpretive

qualitative study with the purpose of better understanding eleventh graders’ decision-making

capacity and what characterizes it concerning the social issues that emerge in their daily school

experiences by taking part in an Authoring Cycle [addressed in chapter 4] experience that

considers construction of social agency and language as a mediator. The present study is guided

by this research question: What does eleventh graders’ Authoring Cycle in an EFL classroom reveal about their social agency?

Type of Study

To answer the research question, this study is framed within the characteristics of a

descriptive and interpretive qualitative research (Creswell, 2014; Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). The

qualitative paradigm is appropriate for this research because my goal is to gain an insider

perspective in order to describe and interpret students’ construction of a sense of social agency

(Creswell, 2014).

In this respect, qualitative research goes beyond looking at human beings and social

contexts. My own point of view cannot be enough to give a clear enough picture of students’

decision-making capacity and agency; then, it is necessary to develop specific attitudes and

abilities, transforming the students into research subjects who help me validate conclusions

(Gurdián, 2007) due to the fact that for me as the teacher-researcher it is really important to

avoid bias when interpreting and describing the participant`s declarative statements; that is to

say, that the core of the data emerged from the students. As Altheide & Johnson (1994, cited in

of the values, emotions, beliefs, and other meanings of cultural members, it is imperative to

embrace an interpretivist approach” (p. 582).

Due to the abovementioned, and examining the nature of the study and the given

objectives, the research approach to interpret and describe data is inductive thinking (Glaser &

Strauss, 1999, first published in 1967). In this view, new knowledge grounded in data from the

field of study is built up, which means that the data is structured to reveal new understandings.

Setting

The institution where this project was held is a Catholic private institution named “Santa

Mónica School,”2 located in the northern part of Bogota, Colombia. This school is one of the

seven that exist in Colombia and that entail part of an important and traditional Catholic religious

order all over the world. It attends to the educational needs of about 2200 female and male

students whose families are middle-class and it is certified in the provision of education services

at the kindergarten, primary and secondary levels.

Regarding the school`s philosophy and curriculum, there are three components at the core

of them: Catholic-Christian values, building of knowledge and a component of English teaching

inside the curriculum, which has started a sequential process from kindergarten since 2015. The

aforementioned key elements appear as relevant issues in the mission and vision of the institution

(Institutional Educational Project, 2014), apart from mentioning human development and

acquisition of knowledge the school seeks for its students to be able to contribute to the

construction of a fraternal, equitable, and just society.