Revista de Acústica. Vol. 38. Nos3 y 4 17

Abstract

In a study of psychological evaluation of environmen-tal sounds complex factors in real life situations have to be dealt with. It is necessary to consider from various viewpoints including examination of physical metrics for the evaluation and technical countermeasures to reduce unwanted sound effectively. It is also necessary to find factors for the desirable sound environment, to settle the environmental quality standard of noise taking social background into account and to establish community rule not to produce unnecessary sounds in cooperation with environmental administration of central and local gov-ernments. For such purposes, it is inevitable to consider the temporal aspects such as memory of past experience and prediction of the future. Though it is difficult to veri-fy these aspects objectively, empirical experimental methods are proposed and the results are introduced aim-ing to challenge the evaluation of long-term environmen-tal sounds.

1. Introduction

Hearing is the perception which conveys information along temporal stream and temporal aspects play an im-portant role in the evaluation of sound environment.

Resumen

En un estudio sobre la evaluación psicológica de los sonidos medioambientales hay que tomar en cuenta los factores comple-jos que se pueden dar en situaciones de la vida real. Es necesario considerar este aspecto desde distintos puntos de vista, incluyen-do el análisis de la física métrica para la evaluación, así como las contramedidas empleadas para reducir el ruido no deseado de manera efectiva. También es necesario hallar los factores para el entorno acústico deseado, establecer el estándar de calidad me-dioambiental del ruido, teniendo en cuenta los antecedentes socia-les, así como establecer unas reglas comunitarias, con el fin de no producir ruidos innecesarios; todo esto debe ser realizado en coo-peración con las administraciones medioambientales, a nivel tan-to central como local. Para ello, es inevitable considerar los as-pectos temporales, como son la memoria de las experiencias pa-sadas y la predicción del futuro. Aunque sea difícil verificar estos aspectos de manera objetiva, se proponen métodos empíricos ex-perimentales y se introducen los resultados como un reto para la evaluación a largo plazo de los sonidos medioambientales.

1. Introducción

Oír es la percepción que transporta la información a lo lar-go del tiempo y los aspectos temporales juegan un papel im-portante en la evaluación del entorno acústico. La sonoridad, la

Psychological

evaluation of sound

environment along

temporal stream

Evaluación

psicológica del

entorno acústico a lo

largo del tiempo

Sonoko Kuwano

Department of Environmental Psychology,

Graduate School of Human Sciences,

Osaka University,

1-2 Yamadaoka, Suita,

Osaka, 565-0871 Japan;

kuwano@see.eng.osaka-u.ac.jp

Loudness, noisiness and annoyance are the main aspects of psychological evaluation of environmental sounds [e.g. 1].

These aspects are significantly affected by the tempo-ral factors. For example, the duration of impulsive sounds strongly affect the loudness. There is a good rela-tionship between total energy (LAE) and loudness within

the critical duration of loudness [2-6] . An example is shown in Fig.1 [3].

Noisiness usually increase as the duration of the sound becomes longer and/or the number of events in-creases [7, 8]. An example of the relation between the duration and noisiness is shown in Fig.2 [7].

ruidosidad y la molestia constituyen los principales aspectos de la evaluación psicológica de los sonidos medioambientales [e.g. 1].

Estos aspectos se ven afectados de manera significativa por los aspectos temporales. Por ejemplo, la duración de los ruidos impulsivos afecta fuertemente a la sonoridad. Existe una buena relación entre energía total (LAE) y la sonoridad dentro de la

du-ración crítica de la sonoridad [2-6]. En la Fig. 1 se muestra un ejemplo [3].

La ruidosidad aumenta habitualmente a medida que la du-ración del sonido se alarga y/o que aumenta el número de acon-tecimientos [7, 8]. En la Fig. 2 se muestra un ejemplo de la re-lación entre duración y ruidosidad [7].

Fig.1 Relation between loudness and LAEof impulsive sounds [3]

Fig.2 Relation between noisiness and duration [7]

Figura 1 Relación entre la sonoridad y LAE de los ruidos impulsivos [3]

In the case of unpleasant noise, if it disappears within short period, we can put up with this noise. But if it con-tinues for a long time, we cannot tolerate it even if this noise is not loud. In the experimental study of sleep dis-turbance by noise, for example, it was found that mean-ingful sounds such as songs and peoples’ talk annoyed the participants and were refused to be continuously pre-sented even if their sound levels were low. An example is shown in Fig.3 [9].

Since the author and her colleagues have introduced the relation between the loudness of sounds with short duration and physical metrics [e.g. 10, 11], the author would like to discuss about psychological evaluation of sound environment from wider range of temporal axis in this paper.

2. Temporal Stream

In order to examine how auditory sensation is con-structed in the temporal stream, a psychological method is desirable for measuring the stream of impressions of sounds. For example, in the evaluation of actual sounds, e.g. music, speech, or environmental noises, it is desir-able to evaluate them in conditions similar to daily life as much as possible. Subjective impressions of environ-mental sounds are evaluated on the basis of not only the sounds existing at that time, but the past experience with

En el caso del ruido desagradable, si éste desaparece rápida-mente, podemos aguantarlo. Sin embargo si éste perdura duran-te largo tiempo no lo podremos tolerar, aunque el volumen no sea alto. En el estudio experimental sobre el trastorno del sueño por culpa del ruido, por ejemplo, se descubrió que los ruidos significativos, como son los de las canciones o de las conversa-ciones de la gente, molestaban a los participantes; éstos los re-cordaban como continuamente presentes, aunque los niveles acústicos fueran bajos. En la Fig. 3 se muestra un ejemplo [9].

Habida cuenta de que la autora y sus colegas han intro-ducido la relación entre la sonoridad de los sonidos de corta duración y la física métrica [e.g. 10, 11], la autora quiere de-batir en este artículo sobre la evaluación psicológica del so-nido medioambiental desde una perspectiva más amplia de ejes temporales.

2. El flujo temporal

Con el fin de examinar de qué manera se construye la sen-sación auditiva a lo largo del tiempo (flujo temporal) es desea-ble contar con un método psicológico para medir la corriente de las impresiones de los sonidos. En la evaluación de los soni-dos actuales, como por ejemplo la música, los discursos o los ruidos medioambientales, es deseable evaluarlos al máximo en condiciones similares a las de la vida cotidiana. Se evalúan las impresiones subjetivas de los sonidos medioambientales par-tiendo, no sólo de los sonidos existentes en ese momento, sino

Revista de Acústica. Vol. 38. Nos3 y 4 19

Psychological evaluation of sound environment along tem-poral stream

[image:3.652.286.529.225.468.2]Evaluación psicológica del entorno acústico a lo largo del tiempo

[image:3.652.34.264.227.467.2]Fig.3 Relation between switch-off-behavior of sound and LAeq [9]. The sounds Nos.7 and 8 are songs and peoples’ talk. The co-efficient of correlation was calculated excluding these sounds.

the sound sources or the frame of reference formed by the experience. To take these factors into account would in important cases give an ecological validity. Since the subjective impression along temporal stream cannot be obtained by conventional psychophysical methods, an al-ternative method has been developed [8, 12, 13].

2.1 Method of continuous judgment by category

The method, called “the method of continuous judg-ment by category”, has been developed in order to evalu-ate continuously the impressions of sounds which vary with time [e.g.8, 12, 13]. In the experiment using this method, participants are asked to judge the loudness at each moment using 7 categories from “very loud” to “very soft” by touching the corresponding key. They need not press the key if their impression of loudness does not change. The impression registered on the moni-tor will remain the same. When their impressions of loudness change, they are required to press the appropri-ate key. A computer key board is used as a response box. When the participant presses a key, the corresponding category is displayed on the monitor and the category and the time when he/she presses the key are stored in the computer. One of the merits of this method is that all the data are stored in a computer and can be analyzed from various viewpoints after the experiment is over. An example of responses obtained by the method of continu-ous judgment by category is shown in Fig.4 [14]. The software for this method for a computer is available [15].

2.2 Relation between instantaneous judgment and physical factors

There is a time lag (reaction time) between the pre-sentation of sounds and the participants’ responses to them. The reaction time can be estimated from the coef-ficient of correlation between physical values and partici-pants’ responses. The coefficient of correlation is calcu-lated by shifting the interval between them. The time lag when the highest correlation can be obtained is regarded as the reaction time. Taking the reaction time into

ac-también de las experiencias pasadas, con las fuentes de ruido o sus marcos de referencia establecidos por la experiencia pasa-da. El tener en cuenta estos factores aportaría en los casos im-portantes una validez ecológica. Habida cuenta de que no se puede obtener la impresión subjetiva a lo largo del tiempo con métodos psicológicos convencionales, se ha desarrollado una metodología alternativa [8, 12, 13].

2.1 Método de valoración continua por categoría

El método denominado “método de valoración continua por categoría” fue desarrollado con el fin de evaluar de manera con-tinua las impresiones de los sonidos que varían a lo largo del tiempo [e.g.8, 12, 13]. En el experimento que utiliza este método se pide a los participantes que valoren la sonoridad de cada mo-mento, utilizando 7 categorías, desde “muy alto” hasta “muy bajo”, presionando la tecla correspondiente. No necesitan presio-nar la tecla si su impresión de sonoridad no cambia. La impre-sión registrada en el monitor no cambiará. Cuando su impreimpre-sión de sonoridad cambia, deben presionar la tecla correspondiente. A modo de caja de respuesta se utiliza un teclado de ordenador. Cuando un participante presiona una tecla aparece la categoría correspondiente en el monitor y la categoría y la hora en que el participante presiona la tecla se almacenan en el ordenador. Uno de los méritos de este método es que se almacenan todos los da-tos en un ordenador y que ésda-tos pueden ser analizados desde di-versos puntos de vista, una vez finalizado el experimento. En la Fig. 4 se muestra un ejemplo de las respuestas obtenidas por el método de valoración continua por categoría [14]. El software para la utilización de este método está disponible [15].

2.2 Relación entre la valoración instantánea y los factores físicos

[image:4.652.293.542.501.585.2]Existe un intervalo (tiempo de reacción) entre la presenta-ción de los sonidos y la respuesta de los participantes. Se puede estimar el tiempo de reacción con el coeficiente de correlación entre los valores físicos y las respuestas de los participantes. Se calcula el coeficiente de correlación cambiando el intervalo en-tre ellos. El intervalo obtenido cuando se puede obtener la co-rrelación más alta se define como tiempo de reacción. Tenien-do en cuenta el tiempo de reacción, se calcula la media de las

Fig.4 An example of the record of continuous judgments [14]. The red line indicates sound level and the blue line indicates subjective response.

[image:4.652.31.279.502.586.2]count, the instantaneous judgments sampled every 100 ms are averaged. When loudness or noisiness is judged, usually a good correlation is found between instanta-neous judgments sampled every 100 ms and sound level sampled every 100 ms [12].

It is considered that instantaneous judgments are af-fected by the previous portion of the sounds as well as the sounds at that moment. In our former study [12] the sound energy was averaged during time interval from 0.5 to 6.0 sec and corresponded to the subjective responses sampled every 100 ms. The highest correlation was found when the averaging time was 2.5 sec. If the coefficient of correlation between the averaged physical values and the continuous judgment by category is regarded as an index of the perceptual present, the averaging time which shows the highest correlation with the instantaneous loudness may represent the most appropriate duration of the perceptual present. The duration of 2.5 sec, which showed the highest correlation in the this experiment, is the value close to those proposed as perceptual present by other researchers using other approaches [16]. This finding suggests that even instantaneous judgments are affected by the sound stream.

The results obtained by the method of continuous judgment provide us many aspects to be examined in the evaluation of sound environment. Examples are as fol-lows:

(1) Reaction time may vary according to the kinds of temporal stream and the attitude of listeners.

(2) The evaluation of long-term sound environment may depend on the instantaneous impression, but other factors may have an effect. This is related to memory including cultural, social and cognitive factors

(3) It may also be probable that we may judge the ins-tantaneous impression predicting future sound phenomena along the temporal stream.

3. Overall evaluation and memory

A good correlation is usually found between LAeq and

perception of loudness judged just after listening to fairly short-term sounds [e.g. 10] as well as instantaneous judgements. For the assessment of environmental sounds, it is important to examine the subjective sion of sounds over a long-term period. Overall impres-sion of long-term sound will be judged on the basis of

valoraciones instantáneas de la muestra cada 100 ms. Cuando se valora la sonoridad o la ruidosidad, se obtiene habitualmente una buena correlación entre las valoraciones instantáneas obte-nidas cada 100 ms y el nivel acústico muestreado cada 100 ms. [12].

Se considera que las valoraciones instantáneas están afecta-das por la porción anterior de sonidos, así como por los sonidos del momento. En nuestro estudio anterior [12], se calculaba la media de la energía sonora durante un intervalo entre 0.5 y 0.6 segundos y ésta correspondía a las respuestas subjetivas mues-treadas cada 100 ms. Se obtuvo la correlación más alta cuando el tiempo medio era de 2.5 segundos. Si el coeficiente de corre-lación entre los valores físicos medios y la valoración continua por categoría son considerados como un índice del presente perceptual, el tiempo medio que muestra la correlación más alta con las sonoridad instantánea puede representar la duración más apropiada del presente perceptible. La duración de 2.5 se-gundos, que mostró la más alta correlación en este experimen-to, es el valor que más se aproxima a aquellos propuestos por otros investigadores que utilizan otros enfoques [16]. Este des-cubrimiento sugiere que incluso las valoraciones instantáneas se ven afectadas por el paso del tiempo.

Los resultados obtenidos gracias al método de valoración continua nos aportan muchos elementos para analizarlos en la evaluación del sonido medioambiental. Los ejemplos son los siguientes:

(1) El tiempo de reacción puede variar dependiendo de los tipos de flujo temporal, así como de la actitud de los participantes en el experimento.

(2) La evaluación a largo plazo del entorno acústico puede depender de la impresión instantánea, pero también pueden tener impacto otros factores. Este aspecto tiene que ver con la memoria, que incluye factores culturales, sociales y cognitivos.

(3) También es probable que se pueda juzgar el fenómeno sonoro de predicción del futuro a través de la impresión instantánea a través del tiempo.

3. Evaluación global y memoria

Se suele obtener una buena correlación entre LAeqy la

per-cepción de la sonoridad valorada después de haber escuchado sonidos de corta duración [e.g. 10], así como las valoraciones instantáneas. Para el estudio de los sonidos medioambientales, es importante examinar la impresión subjetiva de los sonidos a través de un periodo largo de tiempo. La impresión global de un sonido de larga duración será valorada a partir de la

memo-Revista de Acústica. Vol. 38. Nos3 y 4 21

Psychological evaluation of sound environment along tem-poral stream

memory and temporal stream of sounds, and various fac-tors may contribute to determining the overall impres-sion. Social surveys are often used to investigate the im-pression of long-term sound and fairly good correlation is often found between LAeq and subjective responses of

the residents [e.g. 17-19]. However, in order to find the effect of crucial factors to improve the sound environ-ment, experimental approach is effective. The author and her colleagues have been examining the factors that con-tribute to the overall impression of sounds.

3.1 Relation between Overall Judgment and Instantaneous Judgment

It is not easy to find the determinants of overall pressions of long-term fluctuating sounds. Overall im-pression is not determined by a simple summation of the impression of a number of individual stimuli or of all the stimuli at each moment which constitute the environment, as Gestalt Psychologists insisted [20]. Overall impression and instantaneous impression are not independent of each other. The overall impression may be determined by giv-ing a kind of subjective weight to the impression of each constituent stimulus. The impression of each constituent stimulus is also affected by the frame of reference formed by the overall context and past experiences [21].

For the evaluation of long-term fluctuating sounds, it would be helpful to measure instantaneous impression and overall impression as well. In the experiment using the method of continuous judgment by category, after the continuous judgments participants are asked to fill in a questionnaire, in which various questions on the overall impression are included so that information for interpret-ing the experimental data can be obtained. The time in-terval between the presentation of sounds and the overall judgment should be chosen carefully. If it is too short, the overall judgments may be made on the basis of the latter portion of the sounds. If it is too long, the impres-sion may become unclear.

An example showing the relationship of overall judg-ment and the average of instantaneous judgjudg-ments is given in Fig.5 [8]). It can be seen that the overall impression just after the instantaneous judgments indicates slightly greater loudness than the average of instantaneous judg-ments. However, overall judgments made one month af-ter the instantaneous judgments indicate much greaaf-ter loudness than the overall judgment just after the instanta-neous judgment. This may reflect a law of memory.

Another example is shown in Fig.6 [12]. It can be seen that the overall judgment is louder than the average

ria y del flujo temporal de los sonidos. Varios factores pueden contribuir a determinar la impresión general. Se utilizan a me-nudo los estudios sociales para investigar la impresión de soni-dos de larga duración y se obtiene muchas veces una buena co-rrelación entre LAeqy las respuestas subjetivas de los residentes

[e.g. 17-19]. Sin embargo, el enfoque experimental es eficaz para hallar los efectos determinantes para mejorar el entorno acústico. La autora y sus colegas han examinado los factores que contribuyen a la impresión general de los sonidos.

3.1 Relación entre Valoración Global y Valoración Instantánea

No es fácil hallar los determinantes de las impresiones ge-nerales de los sonidos fluctuantes a largo plazo. La impresión general no está determinada por la simple suma de la impresión de un número de estímulos o de todos los estímulos que consti-tuye el entorno en cada momento, como insisten los Psicólogos del método Gestalt [20]. La impresión general y la impresión instantánea no son independientes la una de la otra. Se puede determinar la impresión general dando un tipo de peso subjeti-vo a la impresión de cada estímulo constitutisubjeti-vo. La impresión de cada estímulo constitutivo está también afectada por el mar-co de referencia formado por el mar-contexto general y las expe-riencias pasadas [21].

Para la evaluación de los sonidos fluctuantes a largo plazo, sería de gran ayuda medir, tanto la impresión instantánea, como la impresión general. En el experimento que utiliza el método de la valoración continua por categoría, después de emitir las valoraciones, se pide a los participantes que rellenen un cuestionario, en el cual se incluyen varias preguntas sobre la impresión general, de manera que se pueda obtener informa-ción para interpretar los datos experimentales. Se debe elegir con mucho cuidado el intervalo entre la presentación de los so-nidos y la valoración global. Si éste es demasiado corto, se pueden hacer las valoraciones globales partiendo de la última porción de los sonidos. Si es demasiado largo, la impresión puede volverse poco clara.

En la Fig. 5 se presenta un ejemplo que demuestra la rela-ción entre la valorarela-ción global y la media de las valoraciones instantáneas [8]. Se puede observar que la impresión general justo después de las valoraciones instantáneas indica una sono-ridad ligeramente mayor que la media de las valoraciones ins-tantáneas. Sin embargo, las valoraciones globales realizadas un mes después de las valoraciones instantáneas indican sonorida-des mucho más altas que la valoración global justo sonorida-después de la valoración instantánea. Esto puede implicar una ley de la memoria.

of the instantaneous judgment. In order to find out which parts of the instantaneous loudness determine the overall loudness, instantaneous loudness was averaged using a cutoff point of 10, 20, or 30 dB lower than the maximum level, omitting the lower-level parts. It was found that the average with a 30 dB cutoff point had values close to the overall loudness (Fig. 7). Moreover, the average with a 30 dB cutoff point showed the highest correlation with LAeq.

As time passes, the impression of the prominent tion becomes stronger and that of the less prominent por-tion becomes weaker. It is important to find the factors which contribute to the overall impression.

partes de la sonoridad instantánea determinan la sonoridad global, se calculó la media de las sonoridades instantáneas utilizando un punto de corte de 10, 20 o 30 dB por debajo del nivel máximo, omitiendo las partes de los niveles infe-riores. Se descubrió que la media con un punto de corte de 30 dB tenía valores próximos a la sonoridad global (Fig. 7). Además, la media con un punto de corte de 30 dB mostró la más alta correlación con LAeq.

[image:8.652.76.313.338.527.2]Con el paso del tiempo, la impresión de la porción destacada se vuelve más fuerte y la impresión de la por-ción menos destacada se vuelve más débil. Es importante encontrar los factores que contribuyen a la impresión ge-neral.

[image:8.652.339.581.340.527.2]Fig.5 Overall noisiness judgments made just after the instantane-ous judgments (blue circles) and those made one month after the instantaneous judgments (red diamonds) are plotted against the average of instantaneous judgments [8].

Fig.6 Relation between overall judgment and the average of ins-tantaneous judgments [12]

[image:8.652.354.536.607.793.2]Figura 6 Relación entre la valoración global y la media de las va-loraciones instantáneas [12]

[image:8.652.95.279.608.795.2]Revista de Acústica. Vol. 38. Nos3 y 4 25 Psychological evaluation of sound environment along

tem-poral stream

Evaluación psicológica del entorno acústico a lo largo del tiempo

3.2 Memory of environmental sounds

It is clear that long-term overall impression of sounds is judged on the basis of memory. Generally, annoyance asked in social surveys is judged on the basis of memory of past experience. It is important to examine the long-term effect of noise in actual living environment. How-ever, sounds do not always exist at the moment when long-term impression of sound is judged on the basis of memory. It is interesting and important to examine whether psychophysical law exists relating physical met-rics and subjective impressions of long-term sounds.

Memory of long-term sounds may be influenced by various factors. Among them cognitive and temporal factors may have a significant effect on the memory of environmental sounds. As introduced in the former chap-ter, it was found that the overall impression is not always the same as the average of instantaneous perception of loudness, but usually overall impression is overestimated compared with the average of instantaneous judgments [8, 12]. This suggests that the prominent portions may have greater contribution to the overall impression than less prominent portions. The author and her colleagues are investigating memory of environmental sounds by doing laboratory experiments.

3.2.1 Prominent sound

An experiment was conducted in order to make clear which portions of the sound are prominent and easily memorized and how they contribute to the overall im-pression asking participants to recall the sound sources

3.2 Memoria de los sonidos medioambientales

Está claro que se juzga la impresión general de los sonidos a largo plazo basándose en la memoria. Generalmente la mo-lestia por la cual se pregunta en las encuestas se juzga por la memoria de experiencias pasadas. Es importante examinar el efecto a largo plazo del ruido en el entorno social actual. Sin embargo, los sonidos no siempre existen en el momento en el que la impresión del sonido a largo plazo es valorada a partir de la memoria. Es interesante e importante examinar si existe una ley psicológica que relacione la física métrica y las impre-siones subjetivas de los sonidos a largo plazo.

La memoria de los sonidos a largo plazo puede verse in-fluenciada por varios factores. Entre ellos, los factores cogniti-vos y temporales pueden tener un efecto significativo sobre la memoria de los sonidos medioambientales. Tal y como se ha mencionado en el capítulo anterior, se ha descubierto que la impresión general no es siempre la misma que la media de la percepciones instantáneas de la sonoridad; pero, habitualmente, se sobreestima la impresión general, comparada con la media de las valoraciones instantáneas [8, 12]. Esto sugiere que las porciones destacadas pueden suponer una contribución mayor a la impresión general que las porciones menos destacadas. La autora y sus colegas están investigando la memoria de los soni-dos medioambientales con experimentos de laboratorio.

3.2.1 Sonido prominente

[image:9.652.49.240.104.310.2]Se llevó a cabo un experimento con el fin de aclarar qué porciones del sonido son destacadas y fácilmente memori-zadas y cómo contribuyen a la impresión general; se pidió a los participantes que recordaran las fuentes de ruido y que

Fig.7 Relation between overall judgment and the instantaneous judgments averaged using a cutoff point of 30 dB lower than the maximum level, omitting the lower-level parts. [12]

[image:9.652.314.499.108.309.2]and express their temporal sequences and loudness after instantaneous judgment of loudness using sketch method [14]. A recorded sound in a suburban area in Germany was used without editing. It included various kinds of sounds such as train noise, road traffic noise, human voice, etc. The duration was about 20 min. It was found, as in our former studies, the overall impression was judged louder than the average of instantaneous judg-ments.

Each participant recalled about 15 - 20 sounds on the average after listening the whole sound. Though the number and the kind of the recalled sound sources are different among participants, the recalled sound sources may be regarded as the prominent sounds to the partici-pant. The average of loudness judgment of recalled sounds was calculated for each participant and the judg-ments of six participants were averaged. This average is close to the overall judgments and there was no statisti-cally significant difference between them. It is noticed that the recalled sound sources were not always loud sounds, but many participants recalled the sound of bird twittering whose sound level was fairly low. This result suggests that impressive sounds may contribute to deter-mining the overall impression of loudness including soft sounds.

The maximum levels of train noise, road traffic noise, train crossing, car horns, and bird twittering were corre-lated to the loudness. The result is shown in Fig.8. High correlation was found between them. It was suggested that recalled loudness shows good correlation with physi-cal values. In the following sections factors that affect memory of environmental sounds will be examined.

expresaran sus secuencias temporales y la sonoridad des-pués de las valoraciones instantáneas de la sonoridad, utili-zando el método descrito [14]. Se utilizó una grabación sin editar en un área suburbana de Alemania. Incluía varios ti-pos de sonidos, como ruido de tren, ruidos de tráfico, voces humanas, etc. La duración era de alrededor de 20 minutos. Se descubrió, como en nuestros antiguos estudios, que la impresión general era valorada más alta que la media de las valoraciones instantáneas.

Cada participante recordó, de media, entre 15 y 20 soni-dos después de escuchar toda la grabación. Aunque el nú-mero y el tipo de sonido recordado varían según el partici-pante, las fuentes de ruido recordadas pueden ser considera-das como los sonidos destacados. Se calculó la media de la valoración de la sonoridad de los sonidos recordados para cada participante y se realizó la media de la valoración de seis participantes. Esta media estaba próxima a las valora-ciones globales y no existía una diferencia estadísticamente significativa entre ellas. Hay que señalar que las fuentes de ruido recordadas no eran siempre sonidos fuertes, pero mu-chos participantes recordaron el sonido del piar de un pája-ro, que era bastante débil. Este resultado sugiere que los so-nidos impresionantes pueden contribuir a determinar la im-presión general de sonoridad, incluidos los sonidos leves.

[image:10.652.305.545.583.778.2]Los niveles máximos del ruido del tren, del tráfico, de los pitidos de los coches y del piar de un pájaro fueron rela-cionados con la sonoridad. El resultado se puede ver en la Fig. 8. Se halló una fuerte correlación entre ellos. Esto su-giere que la sonoridad recordada muestra una buena rela-ción con los valores físicos. En las siguientes secciones se analizarán los factores que afectan a la memoria de los soni-dos medioambientales.

[image:10.652.44.279.585.776.2]Revista de Acústica. Vol. 38. Nos3 y 4 27 Psychological evaluation of sound environment along

tem-poral stream

Evaluación psicológica del entorno acústico a lo largo del tiempo

Since the participants do not always recall all the sound sources and there are individual differences in the judgments, many participants are needed for the experi-ment on memory. Therefore, most of the experiexperi-ments were conducted in a group without doing continuous judgments.

3.2.2 Effect of the image of sound sources on the loudness of recalled sound sources

[image:11.652.34.544.618.802.2]In order to recall the sounds some period after listen-ing to the sound, the sound sources have to be identified. Therefore, sounds audible and easily recognized in our daily life are used in the experiments of memory of envi-ronmental sounds. The sound sources used in our experi-ments are shown in Table 1. These sound sources are overlapped on the background noise as shown in Fig. 9 [22, 23].

There is a possibility that the participants judge the loudness of recalled sound sources on the basis of their image of the sound sources experienced in their daily lives. In order to examine whether loudness is judged on the basis of memorized loudness, not on the subjective im-age of the sound source, two experiments were conducted using the sounds with the original sound level (Exp.1) and with increased sound level by 10 dB (Exp.2) [23].

The loudness judgments made in Experiments 1 and 2 are compared in Fig.10. It was found that all the sound sources were judged louder in Experiment 2 than in Ex-periment 1 reflecting the change of the sound level. This suggests that the participants did not judge the loudness on the basis of the subjective image of the sound sources alone, but judged the loudness of the sounds they listened to and that they could memorize and recall the loudness of each sound source.

Table 1 Sound sources used in the experiments [22, 23]

Habida cuenta de que los participantes no siempre recuerdan todas las fuentes de ruido y existen diferencias individuales en las valoraciones, se necesitan muchos participantes para el expe-rimento sobre la memoria. Por lo tanto, la mayoría de los experi-mentos fueron llevados a cabo en un grupo sin realizar valora-ciones continuas.

3.2.2 Efecto de la imagen de las fuentes de ruido sobre la sonori-dad de las fuentes de ruido recorsonori-dadas

Con el fin de recordar los sonidos cierto tiempo después de haberlos escuchado, hay que identificar las fuentes de ruido. Por lo tanto, en los experimentos sobre la memoria de los sonidos medioambientales se utilizan sonidos audibles y fácilmente reco-nocibles en nuestra vida cotidiana. En la Tabla 1 se muestran las fuentes de ruido utilizadas en nuestros experimentos. Estas fuen-tes de ruido se solapan con el ruido antecedente, como se puede observar en la Fig. 9 [22, 23].

Existe una posibilidad de que los participantes valoren la so-noridad de las fuentes de ruido recordadas a partir de la imagen que tienen de las fuentes de ruido en sus vidas cotidianas. Con el fin de examinar si se valora la sonoridad a partir de la sonoridad memorizada, y no de la imagen subjetiva de la fuente de ruido, se han llevado a cabo dos experimentos utilizando los ruidos con el nivel acústico original (Exp. 1) y con un nivel acústico incre-mentado en 10 dB (Exp. 2) [23].

En la Fig. 10 se comparan las valoraciones de la sonoridad realizadas en los Experimentos 1 y 2. Se descubrió que todas las fuentes de ruido fueron valoradas más altas en el Experimento 2 que en el 1, reflejando así el cambio de nivel acústico. Esto su-giere que los participantes no valoraron la sonoridad únicamente a través de la imagen subjetiva de las fuentes de ruido, sino que valoraron la sonoridad de los sonidos que escucharon y que pu-dieron memorizar y recordaron la sonoridad de cada fuente de ruido.

Tabla 1 Fuentes de ruido utilizadas en los experimentos [22, 23]

no sound source L

Aeq

1 melody of a mobile phone 43.7

2 footsteps 57.6

3 train noise 55.6

4 vacuum cleaner 56.0

5 dish washing 40.0

6 people’s talk 40.6

7 aircraft noise 56.6

8 fire engine 51.5

9 dog barking 61.7

10 telephone bell 53.0

11 road traffic noise 55.8

12 printer 45.1

nº fuente de ruido LAeq

1 melodía de un teléfono móvil 43.7

2 pisadas 57.6

3 ruido de un tren 55.6

4 aspiradora 56.0

5 lavaplatos 40.0

6 conversaciones 40.6

7 ruido de avión 56.6

8 camión de bomberos 51.5

9 ladrido de perro 61.7

10 teléfono 53.0

11 ruido de tráfico 55.8

Figura.9 Modelo del nivel acústico de los estímulos utilizados en los experimentos [22, 23].

3.2.3 Effect of the period between listening to sound and recall

The period between listening to sound and recall may have an important effect of the result of experiments on memory. In the case of laboratory experiments there is a merit that experimental factors can be controlled. On the other hand, it is not easy to settle various conditions, espe-cially in the experiments of memory since reinforcement may affect if the experiments are repeated with the same participants. Therefore usually about 100 participants join for one of experimental conditions in our experiments.

In one of our experiments [22] the effect of the period between listening to sound and recall was examined. The participants were asked to recall the sound sources and judge their loudness just after listening to the sound (Exp.1) and 5-11 weeks after listening to the sound (Exp.2). It was found that the percentages of correct

re-3.2.3 Efecto del periodo entre la escucha del sonido y su recuerdo

El periodo entre la escucha y el recuerdo de un sonido pue-de tener un efecto importante sobre el resultado pue-de estos expe-rimentos. En el caso de los experimentos de laboratorio, existe la ventaja de que se pueden controlar los factores experimenta-les. Por otro lado no es fácil establecer varias condiciones, es-pecialmente en los experimentos sobre la memoria si éstos se repiten con los mismos participantes. Por lo tanto, habitual-mente se cuenta con unos 100 participantes para una de las condiciones experimentales en nuestro experimento.

En uno de nuestros experimentos [22] se examinó el efecto del periodo entre la escucha de un sonido y su recuerdo. Se pi-dió a los participantes que recordaran las fuentes de ruido y que valoraran su sonoridad justo después de haber escuchado el sonido (Exp. 1) y 5-11 semanas después de su escucha (Exp. 2). Se descubrió que los porcentajes de un recuerdo

[image:12.652.51.279.270.504.2] [image:12.652.309.537.272.504.2]co-Fig.9 Sound level pattern of the stimulus used in the experiments [22, 23].

Fig.10 Relation between recalled loudness in Experiments 1 and 2 [23]

call of each sound source decreased in Exp.2 compared with those in Exp.1. Also the relation between LAeq and

the loudness of each component sound was lower in Exp.2 (r=.568) than in Exp.1 (r=.720). This suggests that memorized sound sources and their impression of loud-ness may change as the elapse of time.

3.2.4 Effect of the method of measurement of memory

The method to examine memory may have an effect on the results. The difference between recall and recog-nition was examined in our former study [23]. Two weeks after the presentation of the sound (see Table 1 and Fig.8), the participants were requested to recall the sound sources and judge their loudness. Immediately af-ter this experiment a list of sound sources was distributed to the participants in which the names of twenty sound sources were indicated including twelve sound sources actually presented. The participants were requested to judge whether they listened to the sound sources two weeks before and judge the loudness of selected sound sources. The result showed that the percentages of recognition were higher than those of recall. Recognition is usually easier than recall as found in this example.

It is considered that subjectively prominent sounds may have a great contribution to the overall impression of long-term sounds as shown in some sections in this pa-per. Prominent sounds are impressive to the listeners and will be memorized clearly. Therefore they are easily re-called. It would be important to take the method of mea-surement into account when we consider the experimen-tal design and discuss about the results of experiments in the evaluation of environmental sounds.

3.2.5 Relation between loudness of component sounds and overall loudness

As introduced in a former section, the overall judg-ment is usually louder than the average of instantaneous judgments. In the experiment of memory, the overall loudness is also evaluated and compared with the average of the loudness of recalled sound sources. No systematic difference was found between them. This suggests that the recalled sound sources are the prominent sounds to the participants and contribute to the overall impression of loudness though the recalled sound sources are differ-ent among the participants.

4. Habituation

With the elapse of time, subjective impressions of sounds may possibly change. Scharf [24] has indicated

rrecto de cada fuente de ruido descendían en el Exp. 2, compa-rado con el Exp. 1. También, la relación entre LAeqy la

sonori-dad de cada sonido era más bajo en el Exp. 2 (r=.568) que en el Exp.1 (r=.720). Esto sugiere que las fuentes de ruido memo-rizadas y su impresión de sonoridad pueden variar con el paso del tiempo.

3.2.4 Efecto del método de medida de la memoria

El método utilizado para examinar la memoria puede tener un efecto sobre los resultados. La diferencia entre recuerdo y reconocimiento fue examinada en nuestro estudio anterior 23]. Dos semanas después de la presentación del sonido (véase Ta-bla 1 y Fig. 8), se pidió a los participantes que recordaran las fuentes de ruido y valoraran su sonoridad. Inmediatamente des-pués de este experimento se distribuyó una lista con 20 fuentes de ruido identificadas por sus nombres, incluyendo 12 fuentes que fueron efectivamente presentadas. Se pidió a los partici-pantes que identificaran las fuentes escuchadas dos semanas antes y que valoraran la sonoridad. El resultado mostró que los porcentajes de reconocimiento eran mayores que los de recuer-do. Reconocer es más fácil que recordar, como se puede ver en este ejemplo.

Se considera que los sonidos subjetivamente destacados pueden ser una gran contribución a la impresión general de los sonidos a largo plazo, como se puede observar en ciertas secciones de este artículo. Los sonidos destacados son im-presionantes para los oyentes y serán claramente memoriza-dos. Por lo tanto serán también fácilmente recordamemoriza-dos. Sería importante tener en cuenta el método de medida cuando se considere el diseño experimental y se discuta sobre los re-sultados de los experimentos en la evaluación de los sonidos medioambientales.

3.2.5 Relación entre la sonoridad de los sonidos componentes y la sonoridad global

Como ya se ha mencionado en la sección anterior, la valo-ración global suele ser de mayor sonoridad que la media de las valoraciones instantáneas. En el experimento sobre la memo-ria, se evalúa y compara también la sonoridad global con la media de las sonoridades de las fuentes de ruido recordadas. No se encontró una diferencia sistemática entre ellas. Esto su-giere que, para los participantes, las fuentes de ruido recorda-das son los sonidos destacados y contribuyen a la impresión general de la sonoridad, a pesar de que las fuentes de ruido re-cordadas son diferentes para cada participante.

4. Habituación

that with low level sounds and high frequency sounds loudness adaptation occurs, and the impression of loud-ness decreases when the sounds are presented for a longer time.

Habituation to sounds is the phenomenon where, when a certain stimulus is repeatedly presented to the auditory or-gan, the response to the stimulus gradually diminishes and finally no response will occur. Habituation is different from adaptation or fatigue in the point that it is easy to overcome habituation when attention is directed to the stimulus. It is not easy to measure habituation by conventional psycholog-ical methods where participants have to pay attention in or-der to judge the stimulus. In experiments using the method of continuous judgment by category participants are not necessarily forced to pay attention to the specific stimuli all the time. This makes it possible to approach a measurement of habituation [25, 26]

When the duration of the sound is long, participants may not pay attention to sounds all the time, i.e. they may not be conscious of the existence of sounds some of the time and do not respond even if required to do so. This may happen especially when participants are devot-ed to a mental task or when other stimuli are also present. The effect may be reflected in the number of responses. It was found that the number of responses decreases when subjects are habituated to noise.

The method of continuous judgment by category was found to be a useful tool for the measurement of habitua-tion. In an experiment [25] participants were engaged on a mental task and they were highly motivated to do the task. While occupied with the mental task they were asked to judge the noisiness of sounds continuously, us-ing the method of continuous judgment by category. The sounds were of various kinds, such as road traffic noise, voices of street vendors, TV talk, sounds from a washing machine and a vacuum cleaner. The duration of an experimental session was about one hour and a half. In this experiment when participants did not respond to the sounds for 30 s. they were given a signal on a moni-tor to respond. Participants did not always respond to the sounds in spite of the warning signal when they were devoted to the mental task. The length of time when participants did not respond even if the warning signal was presented was used as an index of habituation. There was a high correlation between two trials in the habituation period for each participant. It was also found that the group of participants who showed long periods of habituation said, in answer to a questionnaire, that they became habituated to noise fairly easily in dai-ly life situations.

ruidos de alta frecuencia se puede producir la adaptación de la sonoridad, y la sensación de sonoridad disminuye cuando los ruidos están presentes por periodos más largos.

La habituación a los sonidos es el fenómeno que consiste en que cuando se presenta cierto estímulo repetidamente a un auditorio, las respuestas al estímulo disminuyen gradualmente y finalmente desaparecen. La habituación es distinta de la adaptación o la fatiga, en el sentido de que es fácil superar la habituación cuando se dirige la atención hacia el estímulo. No es fácil medir la habituación con métodos psicológicos conven-cionales, donde los pacientes deben prestar atención para juz-gar el estímulo. En los experimentos que utilizan el método de valoración continua por categoría, los participantes no deben necesariamente prestar atención al estímulo específico todo el tiempo. Esto hace posible aproximarse a una medida de la ha-bituación [25, 26].

Cuando la duración del sonido es larga, los participantes pueden no prestar atención a los sonidos todo el tiempo, por lo tanto pueden no ser conscientes de la existencia de soni-dos en determinasoni-dos momentos y ni siquiera responden cuando son requeridos. Esto puede ocurrir especialmente cuando los participantes están ocupados en un ejercicio mental o si se presentan también otros estímulos. Puede re-flejarse el efecto en el número de respuestas. Se descubrió que el número de respuestas desciende cuando los partici-pantes están habituados al ruido.

Revista de Acústica. Vol. 38. Nos3 y 4 33 Psychological evaluation of sound environment along

tem-poral stream

Evaluación psicológica del entorno acústico a lo largo del tiempo

Another index of habituation is the number of responses made [27]. When participants pay attention to sounds, they re-spond to each change in their impression of sounds. On the other hand, when they are habituated to sounds, they are not conscious of the change and do not respond.

Habituation is closely related to annoyance. If we are ha-bituated to a certain sound, we are not annoyed by the sound. However, if we cannot be habituated to a sound and it is repeat-ed, the sound will become noise. Such cases sometimes hap-pen in neighbourhood noise. Habituation is an important phe-nomenon when we consider the sound environment. It would be important to decrease the sound that is difficult to be habitu-ated to. The method of continuous judgment by category is a good method to examine habituation that cannot be measured by conventional psychophysical methods.

5. Prediction of future

We can behave properly in our daily life without special consciousness. However, our proper behavior is based on our memory of our past experience, perception and cognition of the present situation and the prediction of the future. Since we can predict the future, we can avoid the dangerous happenings. In the evaluation of sound environment, also we can predict how the sound will change in the future on the basis of memory and the perception and cognition of the present situation.

5.1 Prediction of future in the continuous judgment

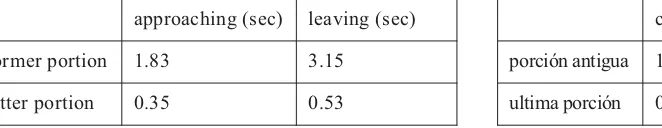

[image:17.652.85.416.762.826.2]There is a time lag between listening to a sound and the subjective response to it. In the method of continuous judg-ment by category, reaction time is estimated by calculating the coefficient of correlation between the sound levels and the sub-jective responses. Since the reaction time may be considered to be different when the change of the sound level can be pre-dicted, the coefficient of correlation was calculated dividing the portions of an aircraft noise in the continuous judgment. It was found that the reaction time was longer in the former unpre-dictable portions of the sound level than the latter preunpre-dictable portions as shown in Table 2. This finding suggests that the participants responded by their prediction of the change of the sound.

Table 2 Reaction time to the loudness of aircraft noise by the met-hod of continuous judgment by category

Otro índice de la habituación es el número de respuestas rea-lizadas [27]. Cuando los participantes prestan atención a los soni-dos, responden a cada cambio. Pero cuando están habituados a los sonidos no son conscientes de los cambios y no contestan.

La habituación está muy relacionada con la molestia. Si es-tamos habituados a cierto sonido, este sonido no nos molestará. Sin embargo, si no podemos habituarnos a un sonido y éste se repite, el sonido se convertirá en ruido. Estos casos se dan a menudo con los ruidos del barrio. La habituación es un fenó-meno importante, si consideramos el sonido medioambiental. Sería importante hacer disminuir el sonido al que es difícil ha-bituarse. El método de valoración continua por categoría cons-tituye un buen método para examinar la habituación que no se puede medir con métodos psicológicos convencionales.

5. Predicción del futuro

Podemos comportarnos convenientemente en nuestra vida cotidiana sin ser especialmente conscientes de ello. Sin embargo, nuestro propio comportamiento está basado en la memoria de nuestra experiencia pasada, en la percepción y el conocimiento de la situación presente y en la predicción del futuro. Ya que podemos predecir el futuro, podemos evi-tar los acontecimientos peligrosos. En la evaluación del so-nido medioambiental también podemos predecir cómo cam-biará el sonido en el futuro, basándonos en la memoria y en la percepción y conocimiento de la situación actual.

5.1 Predicción del futuro en la valoración continua

Existe un intervalo de tiempo entre la escucha de un sonido y la respuesta subjetiva a éste. En el método de valoración con-tinua por categoría, se estima el tiempo de reacción calculando el coeficiente de correlación entre los niveles acústicos y las respuestas subjetivas. Habida cuenta de que el tiempo de reac-ción puede considerarse diferente cuando se puede predecir el cambio de nivel acústico, se calculó el coeficiente de correla-ción dividiendo las porciones del ruido de un avión en valora-ciones continuas. Se descubrió que el tiempo de reacción era más largo en las antiguas porciones de nivel acústico imprede-cibles que en las últimas porciones predeimprede-cibles, como se mues-tra en la Tabla 2. Este descubrimiento sugiere que los partici-pantes responden por su predicción del cambio de sonido.

Tabla 2 Tiempo de reacción de la sonoridad de un ruido de avión por el método de valoración continua por categoría

comienzo (segundos) final (segundos)

porción antigua 1.83 3.15

ultima porción 0.35 0.53

approaching (sec) leaving (sec)

former portion 1.83 3.15

5.2 Subjective response on the basis of the future prediction

When the temporal stream of sounds has some regu-larity and it is recognized, we can predict and control our responses to it. In our former study [28] perceived synchronization between the first beat of a rhythm and delayed visual signal was examined. The sound signal consisted of four sounds, the first sound of which has a stress so that the four sounds make a rhythm. The visu-al signvisu-al was presented only once close to the first beat of the four sounds. When participants pressed a key on a computer keyboard, the visual signal was presented. There was a delay between the key press of the partici-pants and the presentation of the visual signal. The task of the participants was to press a key so that the first beat of the sound signals and the visual signal might be perceived as being presented simultaneously taking the delay of the presentation of the visual signal into ac-count. This means that the participants should press the key predicting the timing of both signals. The results showed that the participants could recognize the tempo-ral stream and press the key properly predicting the tim-ing.

6. Final remarks

A study of psychological evaluation of environmen-tal sounds has to be considered from various viewpoints including examination of physical metrics for the evalu-ation and technical countermeasures to reduce unwanted sound effectively. It is also necessary to find factors for the desirable sound environment, to settle the environ-mental quality standard of noise taking social back-ground into account and to establish community rule not to produce unnecessary sounds in cooperation with en-vironmental administration of central and local govern-ments. For such purposes, it is inevitable to consider the temporal aspects such as memory of past experience and prediction of the future. Though it is difficult to verify these aspects, in this paper empirical experimen-tal methods and the results were introduced aiming to challenge the evaluation of long-term environmental sounds.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to Professor Emeritus Seiichiro Namba of Osaka University for his valuable advice and comments on this paper.

5.2 Respuesta subjetiva en base a la predicción futura

Cuando el flujo temporal de los sonidos tiene cierta regularidad y es reconocido, podemos predecir y contro-lar nuestras respuestas. En nuestro anterior estudio [28] se examinó la sincronización percibida entre el primer compás de un ritmo y la señal visual retrasada. La señal sonora consistió en cuatro sonidos, el primero de ellos con especial énfasis, haciendo que los cuatro sonidos for-masen un ritmo. La señal visual fue presentada única-mente una vez, muy cerca del primer compás del ritmo. Se presentaba la señal visual al presionar los participan-tes una tecla del ordenador. Existía un retraso entre el momento de presionar la tecla y la presentación de la se-ñal visual. La tarea de los participantes consistía en pre-sionar una tecla de manera que pudiera parecer que el primer compás de las señales sonoras y la señal visual eran presentados a la vez, teniendo en cuenta el retraso de la presentación de la señal visual. Esto significa que los participantes debían presionar la tecla prediciendo la aparición de las dos señales. Los resultados mostraron que los participantes podían reconocer el flujo temporal y presionar correctamente la tecla prediciendo el ritmo.

6. Consideraciones finales

Un estudio sobre la evaluación psicológica de los so-nidos medioambientales debe ser considerado desde va-rios puntos de vista, incluyendo el análisis de la física métrica para la evaluación, así como las contramedidas técnicas para reducir de manera eficaz el ruido no desea-do. También es necesario encontrar factores para el en-torno acústico deseable con el fin de establecer el están-dar de calidad medioambiental del ruido, teniendo en cuenta los antecedentes sociales y estableciendo una re-gla social para evitar la producción de ruidos innecesa-rios, todo ello en cooperación con las administraciones medioambientales tanto a nivel central como local. A tal efecto, es inevitable considerar los aspectos temporales, como son la memoria de la experiencia pasada y la pre-dicción del futuro. Aunque sea difícil verificar estos as-pectos, en este artículo se han presentado métodos expe-rimentales empíricos, y se han introducido los resultados con el propósito de plantear como un reto la evaluación de los sonidos medioambientales a largo plazo.

Agradecimientos

Revista de Acústica. Vol. 38. Nos3 y 4 35 Psychological evaluation of sound environment along

tem-poral stream

Evaluación psicológica del entorno acústico a lo largo del tiempo

References. Referencias

[1] S. Namba, “On the psychological measurement of loud-ness, noisiness and annoyance: A review”, Journal of the Acoustical Society of Japan (E), 8, 211-222 (1987).

[2] S. Kuwano, S. Namba and S. Kato, “Loudness of impul-sive sound”, Journal of the Acoustical Society of Japan, 34, 316-317.

[3] S. Kuwano and S. Namba, “On the dynamic character-istics of hearing and the loudness of impulsive sounds”, Transactions of the Technical Committee on Noise, Acoustical Socity of Japan, N-8303-13, 79-84 (1983).

[4] S. Kuwano, S. Namba, H. Miura and H. Tachibana, “Evaluation of the loudness of impulsive sounds using sound exposure level based on the results of a round robin test in Japan”, Journal of the Acoustical Society of Japan (E), 8, 241-247 (1987).

[5] T. Sone, K. Izumi, S. Kono, Y. Suzuki, Y. Ogura, M. Ku-magai, H.Miura, H. Kado, H. Tachibana, K. Hiramatsu, S. Namba, S. Kuwano, O. Kitamura, M. Sasaki, M. Ebata and T. Yano, “Loudness and noisiness of repeated impact sound: Results of round robin tests in Japan (II)”, Journal of the Acoustical Society of Japan (E), 8, 249-261 (1987).

[6] S. Kuwano, H. Fastl and S. Namba, “Relation between loud-ness of sounds with under critical duration and LAeq(2) in the

case of impulsive noise”, Proceedings of the spring meeting of the Acoustical Society of Japan, 757-758 (2007).

[7] S. Kuwano, S. Namba and Y. Nakajima, “On the noisi-ness of steady state and intermittent noises”, Journal of Sound and Vibration, 72, 87-96 (1980).

[8] S. Namba and S. Kuwano, “The relation between overall noisiness and instantaneous judgment of noise and the effect of background noise level on noisiness”, Journal of the Acoustical Society of Japan (E), 1, 99-106 (1980).

[9] S. Kuwano, S. Namba, T. Mizunami and M. Morinaga, “The effect of different kinds of noise on the quality of sleep under the controlled conditions “, Journal of Sound and Vibration, 250 (1), 83-90 (2002).

[10] S. Namba and S. Kuwano, “Psychological study on Leq as a measure of loudness of various kinds of nois-es”, Journal of the Acoustical Society of Japan (E), 5, 135-148 (1984).

[11] S. Kuwano, “Temporal aspects in the evaluation of en-vironmental noise”, Proceedings of the International Congress on Noise Control Engineering, 109-119 (2000).

[12] S. Kuwano and S. Namba, “Continuous judgment of level-fluctuating sounds and the relationship between overall loudness and instantaneous loudness”, Psycho-logical Research, 47, 27-37 (1985).

[13] S. Kuwano, “Continuous judgment of temporally fluc-tuating sounds”, in H. Fastl, S. Kuwano and A. Schick (Eds.),Recent Trends in Hearing Research, (BIS, Old-enburg, 1996), pp.193-214.

[14] S. Kuwano, S. Namba, T. Kato and J. Hellbrueck, “ Memory of the loudness of sounds in relation to

over-all impression”, Acoustical Science and Technology, 24 (4), 194-196 (2003).

[15] S. Namba, S. Kuwano, H. Fastl, T. Kato, J. Kaku and K. Nomachi, “Estimation of reaction time in continu-ous judgment”, Proceedings of International Congress on Acoustics, 1093-1096 (2004).

[16] P. Fraisse, Psychology du Temps, (Press University, 1957), (Japanese translation by Y. Hara, revised by K. Sato).

[17] T. J, Schultz, “Synthesis of social surveys on noise an-noyance”, Journal of the Acoustical Society of Ameri-ca, 64, 377-405 (1978).

[18] H. M. E. Miedema and H. Vos, “Exposure-response relationships for transportation noise”, Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 104 (6), 3432-3445 (1998).

[19] J. Kaku, M. Kabuto, T. Kageyama, K. Kuno, S. Kuwano, S. Namba, S. Sueoka, H. Tachibana, K. Ya-mamoto, M. Yamashita, and K. Kamigawara: Stan-dardization of social survey method in Japan, Proceed-ings of Inter-noise 2004?CD-ROM (2004).

[20] J. Hochberg, “Organization and the Gestalt tradition”, in Handbook of Perception, Vol.1, edited by E. C. Carterette and M. P. Friedman, (Academic Press, New York, 1974), pp.179-210.

[21] H. Helson, Adaptation Level Theory, (Harper & Row, 1964).

[22] S. Kuwano, S. Namba and T. Kato, “Memory of the loudness of sounds using sketch method”, Proceedings of International Congress on Noise Control Engineer-ing, CD-ROM, (2003).

23] S. Kuwano, S. Namba and T. Kato, “Perception and memory of loudness of various sounds”, Proceedings of International Congress on Noise Control Engineering, CD-ROM, (2006).

[24] B. Scharf, “Loudness adaptation”, in Hearing Researcha and Theory, Vol.2, edited by J. V. Tobias and E. D. Schu-bert, (Academic Press, New York, 1983), pp. 1-57.

[25] S. Namba and S. Kuwano, “Measurement of habitua-tion to noise using the method of continuous judgment by category”, Journal of Sound and Vibration, 127, 507-511 (1988).

[26] S. Namba, S. Kuwano, A. Kinoshita and Y. Hayakawa, “Psychological evaluation of noise in passenger cars -The effect of visual monitoring and the measurement of habituation”, Journal of Sound and Vibration, 205, 427-434 (1997).

[27] N. Hato, S. Kuwano and S. Namba, “A measurement method of car interior noise habituation”, Transactions of the Technical Committee on Noise, the Acoustical Society of Japan, N95-48, 1-4 (0995).

![Fig.1 Relation between loudness and LAE of impulsive sounds [3]](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_es/5458703.111310/2.652.306.526.546.758/fig-relation-loudness-lae-impulsive-sounds.webp)

![Fig.3 Relation between switch-off-behavior of sound and LAeq[9]. The sounds Nos.7 and 8 are songs and peoples’ talk](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_es/5458703.111310/3.652.286.529.225.468/relation-switch-behavior-sound-laeq-sounds-songs-peoples.webp)

![Figura 4 Ejemplo de registro de valoraciones continuas [14]. Lalínea roja indica el nivel acústico y la línea azul indica la respues-ta subjetiva.](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_es/5458703.111310/4.652.293.542.501.585/figura-ejemplo-registro-valoraciones-continuas-lalinea-acustico-subjetiva.webp)

![Fig.5 Overall noisiness judgments made just after the instantane-ous judgments (blue circles) and those made one month after theinstantaneous judgments (red diamonds) are plotted against theaverage of instantaneous judgments [8].](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_es/5458703.111310/8.652.354.536.607.793/noisiness-judgments-instantane-judgments-theinstantaneous-theaverage-instantaneous-judgments.webp)

![Figura 7 Relación entre la valoración global y las valoracionesinstantáneas cuya media ha sido obtenida utilizando un punto decorte de 30 dB por debajo del nivel máximo, omitiendo las partesde los niveles inferiores [12].](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_es/5458703.111310/9.652.49.240.104.310/relacion-valoracion-valoracionesinstantaneas-obtenida-utilizando-omitiendo-partesde-inferiores.webp)

![Fig.8 Relation between recalled loudness and sound level [14]](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_es/5458703.111310/10.652.44.279.585.776/fig-relation-recalled-loudness-sound-level.webp)

![Table 1 Sound sources used in the experiments [22, 23]](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_es/5458703.111310/11.652.34.544.618.802/table-sound-sources-used-experiments.webp)

![Fig.10 Relation between recalled loudness in Experiments 1 and 2[23]](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_es/5458703.111310/12.652.51.279.270.504/fig-relation-recalled-loudness-experiments.webp)