UNIVERSIDAD TÉCNICA PARTICULAR DE LOJA

La universidad católica de Loja

ESCUELA DE BIOQUÍMICA Y FARMACIA

MODALIDAD PRESENCIAL

“Evaluación del efecto del inóculo

Micorrízico arbuscular en el crecimiento de

Cinchona pubescens

y

Cinchona officinalis

en condiciones de vivero”

Trabajo de fin de carrera previa

a la obtención del título de:

Bioquímico – Farmacéutico

Autoras

:

Guachón Medina Tania Cecilia

Prado Vivar María Belén

Director:

Ing. Lucero Mosquera Hernán Patricio

Loja – Ecuador

CESIÓN DE DERECHOS

Nosotras, Tania Cecilia Guachón Medina y María Belén Prado Vivar,

declaramos conocer y aceptar la disposición del Art. 67 del Estatuto

Orgánico de la Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja que en su parte

pertinente textualmente dice: “Forman parte del patrimonio de la

Universidad la propiedad intelectual de investigaciones, trabajos científicos

o técnicos y tesis de grado que se realicen a través o con el apoyo

financiero, académico o institucional (operativo) de la Universidad”.

Loja, enero de 2012

Tania Cecilia Guachón Medina María Belén Prado Vivar

AUTORA AUTORA

Ing. Hernán Patricio Lucero Mosquera.

CERTIFICACIÓN

Ing.

Hernán Lucero Mosquera.

DIRECTOR DE TESIS

C E R T I F I C O:

Una vez revisado el trabajo de investigación realizado por las alumnas

Tania Cecilia Guachón Medina y María Belén Prado Vivar, previo a la

obtención del título de BIOQUÍMICO FARMACÉUTICO, se autoriza su

presentación final para la evaluación correspondiente.

Loja, enero de 2012

Ing. Hernán Lucero Mosquera.

DIRECTOR DE TESIS

AUTORÍA

Los conceptos, ideas y resultados vertidos en el desarrollo del

presente trabajo de investigación son de absoluta responsabilidad

de sus autoras.

Tania Cecilia Guachón Medina María Belén Prado Vivar

DEDICATORIA

Quiero dedicar mi trabajo de tesis a Dios el dueño de mi vida, a mis Padres: Segundo y

Matilde y a mi hermana Alexandra, por ser los pilares fundamentales de mi vida y quienes

durante todos estos años supieron siempre darme apoyo incondicional y palabras de aliento

cuando me sentía desanimada, sin su ayuda no hubiese podido culminar mi meta.

Tania G.

La presente tesis, la dedico a mi familia que gracias a sus consejos y palabras de aliento he

logrado salir adelante. A mi compañera de tesis Tania, por su apoyo y comprensión a los largo

de todo este proceso. Con todo el cariño y amor les dedico todo mi esfuerzo y la felicidad que

causa en mi cumplir con una etapa mas en mi vida.

AGRADECIMIENTO

A Dios, por ser nuestro guía, y darnos la sabiduría y valor necesario para sobrellevar todos los

obstáculos y terminar con éxito esta investigación. A nuestros padres, por la confianza y apoyo

que han contribuido positivamente para llevar a cabo esta difícil jornada.

A la Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja en cuyas aulas tuvimos la oportunidad de

formarnos integral y profesionalmente, al Centro de Biología Celular y Molecular por

brindarnos los medios para llevar a cabo esta investigación.

Quedamos especialmente agradecidas con nuestros dos directores de tesis, el Ing. Hernán

Lucero y el Ing. Paul Loján, quienes compartieron sus conocimientos, experiencias y guías,

apoyándonos en todo momento con sus acertados comentarios, sugerencias y correcciones que

contribuyó para la finalización del presente proyecto.

A nuestras amigas y compañeros de carrera por apoyarnos y compartir todas las experiencias

buenas y malas que tuvimos durante nuestra vida estudiantil. Y a todas las personas que de

forma directa o indirecta estuvieron ahí de forma incondicional.

CONTENIDO

Pág

CESIÓN DE DERECHOS ii

CERTIFICACIÓN iii

AUTORÍA iv

DEDICATORÍA v

AGRADECIMIENTO vi

CONTENIDO vii

RESUMEN xi

ABREVIATURAS xxii

FIN, PROPÓSITO Y COMPONENTES DEL PROYECTO xxiii

1. INTRODUCCION Y ANTECEDENTES: 1.1 Micorrizas:

1.1.1 Definición 1

1.1.2 Clasificación Morfológica de Micorrizas 1

1.2 Micorrizas Arbusculares:

1.2.1 Descripción de HMA 3

1.2.2 Arquitectura de la micorriza Arbuscular 4

1.2.2.1 Hifas 4

1.2.2.1.1 Hifas intercelulares 4

1.2.2.1.2 Hifa intracelular 4

1.2.2.1.3 Hifa extraradicular 4

1.2.2.2 Apresorios 5

1.2.2.3 Vesículas 5

1.2.2.4 Arbúsculos 5

1.2.2.5 Células Auxiliares 5

1.2.3 Clasificación de los HMA 6

1.3 Simbiosis HMA-Planta hospedera:

1.3.1 Multiplicación de inóculo Micorrízico 7

1.3.2 Plantas hospederas 8

1.3.3 Sustrato 9

1.4 Ciclo simbiótico de HMA 9

1.5.1 Etimología 11

1.5.2 Generalidades y Uso 11

1.5.3 Cinchona officinalis L. 12

1.5.3.1 Descripción taxonómica 12

1.5.3.2 Ubicación geográfica en el Ecuador 12

1.5.3.3 Descripción 13

1.5.4 Cinchona pubescens L. 13

1.5.4.1 Descripción taxonómica 14

1.5.4.2 Ubicación geográfica en el Ecuador 14

1.5.4.3 Descripción 14

1.6 Cultivo invitro de Hongos Micorrízicos Arbusculares

1.6.1 Cultivo monoxénico 14

1.6.2 Raíces Hospederas transformadas 15

1.7 Rol ecológico e Importancia de los HMA en la restauración de ecosistemas degradados 15

1.8 Efectividad e infectividad de los HMA 16

2. METODOLOGÍA

2.1 Sitio de estudio y muestreo 18

2.2 Multiplicación in vivo del inóculo de HMA aislados desde Cinchona pubescens en plantas trampa de Lolium perenne

18

2.3 Determinación del porcentaje de colonización de raíces micorrizadas de las plantas trampa 19

2.4 Condiciones del Ensayo 19

2.5 Parámetros evaluados 21

2.5.1 Determinación del porcentaje de colonización de las plantas Cinchona officinalis y

Cinchona pubescens:

21

2.6 Aislamiento in vitro de HMA 22

2.6.1 METODO 1: Obtención de cultivos monospóricos de HMA in vitro 22

2.6.1.1 Obtención de los propágulos 22

2.6.1.2 Selección de los propágulos de HMA 22

2.6.1.3 Extracción, desinfección y siembra de las esporas 22

2.6.2 METODO 2: Obtención de cultivos de raíces de HMA in vitro. 23

2.7 Análisis estadístico 24

3. RESULTADOS Y ANALISIS

3.1 Evaluación de la colonización de las plantas trampa. 25

3.2 Resultado del “ensayo prueba”. 25

3.3 Evaluación de las plantas de Cinchona officinalis y Cinchona pubescens 26

3.3.1 Mortalidad de las plantas 27

3.3.2 Resultados de las variables respuesta 28

3.3.2.2 Número de Hojas 29

3.3.2.3 Diámetro de tallo 30

3.3.2.4 Tamaño de la raíz 31

3.3.2.5 Tamaño total 32

3.3.2.6 Peso aéreo 33

3.3.2.7 Peso radicular 33

3.3.2.8 Peso seco aéreo 34

3.3.2.9 Peso seco radicular 35

3.3.3 Evaluación del porcentaje de colonización 37

3.3.3.1 Análisis estadístico del porcentaje de colonización. 37

3.3.3.1.1 Frecuencia de Micorrización %F 38

3.3.3.1.2 Abundancia Arbuscular en el sistema radicular %A 39

3.4 Resultados de los cultivos in vitro de HMA 41

3.4.1 Resultados del cultivo monospórico de HMA 41

3.4.2 Resultados del cultivo de raíces de HMA in vitro 42

4. CONCLUSIONES 45

5. PERSPECTIVAS A FUTURO

47

6. BIBLIOGRAFÍA

48

5. ANEXOS 53

LISTA DE TABLAS

Pág.

Tabla 1: Clasificación de los hongos micorrízicos arbusculares. 7 Tabla 2: Tratamientos utilizados para el establecimiento del ensayo. 20 Tabla 3: Porcentaje de mortalidad y supervivencia de las plantas. 27

LISTA DE FIGURAS

Pág. Figura 1: Principales estructuras de los tipos de micorrizas. 3 Figura 2: Representación de un hongo Micorrízico Arbuscular. 4

Figura 3: Estructura de los Hongos Micorrízicos. 6

Figura 4: Ciclo de vida de los HMA durante el establecimiento de la simbiosis funcional. 10

Figura 5: Foto del árbol de Cinchona officinalis. 12

Figura 7: Plantas en el invernadero. 20

Figura 8: Cultivo monospórico de Scutellospora savanicola. 23 Figura 9: Segmentos de raíz con Glomus sp en cultivo in vitro. 24 Figura 10: Estructuras micorrízicas encontradas en las plantas trampa de Lolium perenne. 25 Figura 11: "Ensayo prueba" con plantas de Cinchona officinalis inoculadas con MUCL41883. 26 Figura 12: Evaluación de las variables respuesta de las planta. 26 Figura 13: Evaluación de la colonización de las plantas de Cinchona en estudio. 37 Figura 14: Germinación de Scutellosporasavanicola sobre medio MSR. 42

Figura 15: Cultivo de raíces con Glomus sp. 42

LISTA DE GRAFICAS

Pág.

Gráfica 1: Altura de las plantas 29

Gráfica 2: Número de Hojas de las plantas 30

Gráfica 3: Diámetro de tallo de plantas 30

Gráfica 4: Tamaño de raíz de las plantas 31

Gráfica 5: Tamaño Total de las plantas 32

Gráfica 6: Peso aéreo de las plantas 33

Gráfica 7: Peso radicular de las plantas 34

Gráfica 8: Peso seco aéreo de las plantas 34

Gráfica 9: Peso seco radicular de las plantas 35

Gráfica 10: Porcentaje de Frecuencia de Micorrización 38

Gráfica 11: Porcentaje de Abundancia Arbuscular 39

LISTA DE ANEXOS

Pág. Anexo 1: Datos generales de la planta hospedera (Lolium perenne) 53 Anexo 2: Modificación del Método tinción de Phillips y Hayman (1974). 54 Anexo 3: Distribución de las plantas en el invernadero 55

Anexo 4: Fotos del ensayo 56

Anexo 5: Estimación de la micorrización 60

RESUMEN

Los hongos micorrízicos arbusculares (HMA) son organismos que viven

simbióticamente con la mayoría de plantas. Por el papel clave que juegan

en el desarrollo de plantas invasoras frente a especies nativas; el presente

trabajo estableció un ensayo con 288 plantas entre Cinchona officinalis y

pubescens,

bajo un diseño basado en cuatro tratamientos: inóculo

Galápagos, inóculo MUCL41883, fertilizante y testigo. Evaluamos

parámetros: altura, número de hojas, diámetro de tallo, tamaño radicular y

total, peso fresco y seco, y porcentaje de colonización.

Los resultados

mostraron efectos positivos en tratamientos con HMA, la mayor tasa de

mortalidad se dio con fertilizante. La asociación Cinchona pubescens –

MUCL41833 demostró mayor porcentaje de colonización (92.64%).

También realizamos cultivos in vitro de HMA con esporas de Scutellospora

savanicola

y segmentos de raíces colonizadas con

Glomus sp.

germinadas sobre medio MSR, para luego establecer simbiosis en raíces

transformadas de

Medicago truncatula. Los resultados mostraron que el

cultivo de esporas formó una masa enredada de hifas con distribución

limitada, no así el cultivo de raíces en donde no se evidenció germinación

alguna.

Palabras Clave

: micorrízica, inóculo,

Cinchona

, monoxénico.

SUMARY

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are soil organisms that live

symbiotically with most plants. On the key role they play in growth and

development of invasive plant versus native species, the present work

established a study of 288 plants from Cinchona officinalis and pubescens,

under an experimental design based on four treatments: Galapagos

inoculum, MUCL41883 inoculum, fertilizer and a control. The parameters

evaluated were: height, leaf number, stems diameter, root size, total fresh

and dry weight, and percentage of colonization. The results showed positive

effects in treatment with AMF, but not with fertilizer, which showed higher

mortality rate. Mycorrhizal colonization, the association

Cinchona

pubescens - MUCL41833 showed better results (92.64%).

Also, we realized cultivation

in vitro of AMF spores of

Scutellospora

savanicola and root segments colonized by

Glomus

sp. germinated on

MSR medium, and then establish symbiosis in

Medicago

truncatula roots

transformed. The results indicate that the cultivation of spores showed no

intraradical colonization only the formation of a tangled mass of hyphae with

limited distribution, while root crops failed because there was no evidence

of germination any time.

EVALUATION OF THE EFFECT OF ARBUSCULAR MYCORRHIZAL INOCULUM IN THE GROWTH OF Cinchona officinali ANDCinchona pubescens UNDER GREENHOUSE

CONDITIONS.

María B. Prado1, Tania C. Guachón1, Hernán P. Lucero2, Paul D. Loján2

1

Biochemistry and Pharmacy School~Technical University of Loja, San Cayetano Alto s/n, Postal Code 11-01-608, Loja, Ecuador

e-mail: mbprado@utpl.edu.ec; tcguachon@utpl.edu.ec

2

Center of Molecular and Cell Biology~ Technical University of Loja, San Cayetano Alto s/n, Postal Code 11-01-608, Loja, Ecuador

e-mail: hplucero@utpl.edu.ec; paulojanarmijos@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are soil organisms that live symbiotically with most plants. On the key role they play in growth and development of invasive plant versus native species, the present work established a study of 288 plants from Cinchona officinalis and pubescens, under an experimental design based on four treatments: Galapagos inoculum, MUCL41883 inoculum, fertilizer and a control. The parameters evaluated were: height, leaf number, stems diameter, root size, total fresh and dry weight, and percentage of colonization. The results showed positive effects in treatment with AMF, but not with fertilizer, which showed higher mortality rate. Mycorrhizal colonization, the association Cinchona pubescens - MUCL41833 showed better results (92.64%).

Also, we realized cultivation in vitro of AMF spores of Scutellospora savanicola and root segments colonized by Glomus sp. germinated on MSR medium, and then establish symbiosis in Medicago truncatula roots transformed. The results indicate that the cultivation of spores showed no intraradical colonization only the formation of a tangled mass of hyphae with limited distribution, while root crops failed because there was no evidence of germination any time.

Key words: Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, Inoculum, species of Cinchona, monoxenic cultures.

INTRODUCTION:

The term mycorrhizal derives from the Greek:

myco (fungal) and rhyza (root), it is a symbiosis between the roots of most plants and certain soil fungi (Hernandez et al. 2001), (Read, 1999). Within the type endomycorrhizae find arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), whose name derives from the characteristics that these fungal structures present the arbuscules and vesicles (Gonzales, et al. 2005).

This association benefits the plant in terms of absorption of nutrients, especially of those little mobile as phosphorus (Holguin, et al. 1996), and thanks to the greater volume of soil explored by the extraradical hyphae, the intake of water by the

plant increases, improving tolerance to water stress and stimulate root and air growth (Smith and Read, 1997). This is an environmentally friendly alternative that will reduce the pollution problems caused by over use of chemical fertilizers (Martinez, et al. 2007).

where it has demonstrated severe invasive characteristics. Unlike this species, we find

Cinchona officinalis, a species native to southern Ecuador and considered of great importance for its antimalarial action, but it is threatened and is considered a priority species for conservation and study (Loaiza and Sanchez, 2006), because in natural conditions shows low germination, rate found only in small and remote places.

The aim of our study is based on checking the effect of AMF communities associated with C. pubescens on the island of Santa Cruz - Galapagos on the growth of plants of C.

pubescens and C. officinalis in greenhouse conditions. Also using and applying methods for the isolation of HMA, by using monoxenic cultures, a technique that has managed to produce in vitro culture of roots which have been inoculated with spores of AMF previously disinfected on synthetic media previously.

Consequently, the use of these microsymbionts could be taken into account in the design of any system of agricultural production, because they are considered as biological substitutes of mineral fertilizers (Castillo, et al. 2009).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For this research we used two types of fungal material: one from Santa Cruz Island - Galapagos (S 0.66226, 90.3248 W; from a C. pubescens forest of the Charles Darwin Foundation donated by Heinke Jager) and one strain MUCL41833 of

Rhizophagus irregulare, from the Micoteca Catholic University of Leuven.

The multiplication of the Galapagos inoculum was conducted in pots and in duplicate in 10 host plants of Lolium perenne, and were kept in bags Sun Bags ® for about 4 months. After this time, several roots were extracted at randomly and using the staining method of Phillips and Hayman (1970), and also with the help of the microscope we determined which plants had a higher percentage of colonization, this would be of great importance for our study

1. Experimental design:

Before starting our study, we realized a "trial test", which consisted of ten plants of Cinchona officinalis which were inoculated with MUCL41883 for two months, then evaluated their mycorrhizal colonization by staining and verifying the success of the symbiosis. This was the basis for future studies.

For the main essay (trial), seeds of Cinchona pubescens and Cinchona officinalis were germinated previously in vitro for two months and then were transplanted to pots in the greenhouse.

When the plants showed an appropriate size our assay (trial) began. A total of 144 plants of C. pubescens and 144 of C. officinalis were divided into three blocks, four replications, three replicates by treatment and four treatments, which were: T1= Galapagos inoculum, T2= MUCL41883 inoculum, T3= fertilizer and T4=control.

During the months of May to August, they were under greenhouse conditions for their growth. After this time we proceeded to analyze, the response variables evaluated were: mortality, plant height, leaves number, fresh weight, dry weight and percentage of colonization.

Parameters evaluated:

2. Isolation in vitro of HMA:

Because in our culture no spores were found to implement these methods, the propagules were selected: Scutellospora savanicolla cultures (1455-2), from roots of Cedrela montana

(Mycorrhiza for Reforestation Project) and roots isolation of Glomus sp. (E2-GLO1), from a potato culture of Saraguro (VALORAM Project).

2.1 AMF spore culture in vitro:

S. savanicolla spores were obtained by applying the method of sieving and decanted of Gerdermann and Nicolson (1963), and extracted under a stereoscope, before being subjected to a desinfection process based on the protocol of Cranenbrouck, et al. (2005).

Disinfected spores were captured using a micropipette and sterile tips and deposited in the Modified Strullu Romand Medium (MSR), and incubated in the shade at 27 ° C. Once it was verified the germination of spores were inoculated on Medicago truncatula transformed roots on MSR medium alike.

2.2. Culture roots with AMF in vitro:

Roots isolation of Glomus sp. (E2-GLO1) were washed with tap water to remove every particle of soil.

The disinfection of the root was made based on Cranenbrouck, et al. (2005), with the help of a sonicator and using solutions such as demineralized water, Calcium Hypochlorite, chloramine T solution at 2% and washed with antibiotic solution, and finally fragments of approximately 0.5 cm were selected at random in laminar flow chamber, and with the help of a sterile scapler and forceps five pieces each were placed in Petri plate filled with MSR and incubated at 27 ° C

3. Statistical Analysis:

Data was analyzed with the method of analysis of variance and mean comparison test (Tukey, P

<0.05) using the program Statistical Analysis System (SAS).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ten plants were evaluated Lolium perenne trap through their roots staining using the method of Phillips and Hayman (1970). Under the microscope it was observed that seven of them had great presence of mycorrhizal structures (Fig.1), confirming the multiplication of the Galapagos inoculum, suitable for our trial.

Figure 1: Mycorrhizal structures found in plants to trap Lolium perenne) arbuscules, b) c) vesicles and hyphae.

Assay results:

Two months after inoculation of C. officinalis

plants with MUCL41883, we found that there are plant symbiosis - AMF by staining roots under the method of Phillips and Hayman (1970). This subsequently allowed us to start our test with greater security (Fig. 2).

[image:15.612.317.542.495.603.2]

After three months of growth under green- house conditions, we began to evaluate all of the proposed parameters.

Table 1. Mortality rate of C. pubescens and C. officinalis, with all treatments

Of the 288 plants studied, 133 plants died (46.18%). Also, 36 of the plants used for treatment, presented higher mortality rate in T3, with C. pubescens (88.8%) and C. officinalis

(63.8%) plants, (Table 1).

The highest rate of mortality was due to using very high doses of fertilizers, since its excess causes symptoms similar to the excess of water, also keep in mind that the finer is the root, the greater must be the dilution of fertilizers (Silva, F., 1999).It is also necessary to know the conditions that each plant needs, Morton and Benny (1990) explain that some plant species decrease in number or disappear when attempting to multiply in pots.

Response variables evaluated

• Height

Graph 1. Height plant of C. pubescens and C. officinalis in the four treatments. T1: Inoculum Galapagos, T2: MUCL41833 Inoculum, T3: Fertilizer, T4: Witness. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations. Different letters show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

The species tested showed no significant difference (p = 0.44) between them. While no significant difference between treatments (p = 0.02). In the Graphic 1 we see that T1 - C. officinalis gave better results in height (3.1 cm), while T3 - C. pubescens was the lowest result was that (0.1cm).

The growth rates of plants are related to the association with AMF (Smith and Read, 1997). Most soil exploration have their aerial hyphae increase the absorption of nutrients by taking them to the host plant. (Harrison, 1997), thus increasing the physiological changes in plant growth.

• Number of leaves

Graph 2: Number of leaves of plants of C. pubescens and C. officinalis in the four treatments. T1: Inoculum Galapagos, T2: Inoculum MUCL41833, T3: Fertilizer, T4: Witness. Vertical

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

T1 T2 T3 T4

He ight (c m ) Treatments Height C. pubescens C. officinalis

a ab

bc c 0.00 2.00 4.00 6.00 8.00 10.00 12.00

T1 T2 T3 T4

Num be r of le ave s Treatments

Number of leaves

C. pubescens C. officinalis MORTALITY RATESpecie Treatment Dead Living

Ci n c h o n a Pu b e s c e n s

Galápagos inoculum T1 61.11 % 38.88% MUCL41833 inoculum T2 27.77 % 72.22 % Fertilizer T3 88.88 % 11.11 % Control T4 61.11 % 38.88 %

Ci n c h o n a Of fi c in a lis

Galápagos inoculum T1 13.88 % 86.11 % MUCL41833 inoculum T2 8.33 % 91.66 % Fertilizer T3 63.88 % 36.11 % Control T4 44.44 % 55.55 %

TOTAL 46.18 % 53.81 %

cd

d

[image:16.612.324.552.83.216.2]

lines indicate standard deviations. Different letters show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

Statistically evaluated species showed no significant difference (p = 0.77) between them. Significant difference between treatments (p = 0.0013). The graph 2, indicates that T1 and T2 with C. officinalis gave better results (7 leaves). The lowest score: T3 with C. pubescens was (1 leave).

• Stem Diameter

Graph 3: Stem Diameter of C. pubescens and C. officinalis plants in the four treatments: T1: Galapagos inoculum, T2: MUCL41833 inoculum, T3: Fertilizer, T4: Control. Vertical lines Indicate standard deviations. Different letters show significant Differences (p ≤ 0.05).

The results show that the species tested showed no significant difference (p = 0.94), not was there between treatments (p = 0.20). It is clear to see in Graphic 3, that T1 - C. officinalis gave better results in terms of stem diameter (0.26 cm). While the T3 - C. officinalis was the lowest result that was obtained (0.041 cm).

Hernandez and Chialloux, (2001)., mentioned that the physiological effects that cause the AMF in terms of uptake of moisture and nutrients to appreciate a greater force of the stem and leaf area of plants.

• Size of root

Graph 4: Size of plant root C. pubescens and C. officinalis in the four treatments. T1: Galapagos Inoculum, T2: MUCL41833 Inoculum, T3: Fertilizer, T4: Control. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations. Different letters show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

These results show that the species tested showed significant difference (p = 0.048). Between treatments was not significant

difference (p = 0.11). The best result was with T1 -

C. officinalis (4.075 cm). While the T3 - C. pubescens was the lowest result (0.84 cm).

(Graph 4).

• Total size

Graph 5: Total size of the plants of C. pubescens and C. officinalis in the four treatments. T1: Galapagos Inoculum, T2: MUCL41833 Inoculum, T3: Fertilizer, T4: Control. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations. Different letters show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

0.00 0.10 0.20 0.30 0.40 0.50 0.60 0.70 0.80

T1 T2 T3 T4

Di a met er ( cm) . Treatments

Stem Diameter

C. pubescens C. officinalis aa a a

0.00 1.00 2.00 3.00 4.00 5.00 6.00 7.00

T1 T2 T3 T4

Siz e of plant r oot (c m ) Treatments

Size of root

C. pubescens C. officinalis

a a

a a 0.00 2.00 4.00 6.00 8.00 10.00 12.00

T1 T2 T3 T4

To tal si ze ( cm) Treatments

Total size

C. pubescens C. officinalisa

b

Statistically significant difference was observed between species (p = 0.0006) and between treatments (p = 0.0133). Best we see with T1 - C. officinalis with a total size average of 7.40 cm, compared to T3 - C. pubescens was the lowest with an average of 0.47 cm. (Graph. 5)

Rivera and Fernández, (1997), indicate that the plants colonized by AMF stimulate root development and plants show better growth than non-mycorrhizal, an issue that is related to the above mencionado and as to the further exploration of the root system.

• Aerial Weight

Graph 6: Weight aerial plants of C. pubescens and C. officinalis in the four treatments. T1: Galapagos Inoculum, T2: MUCL41833 Inoculum, T3: Fertilizer, T4: Control. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations. Different letters show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

The results show that the species tested showed no significant difference (p = 0.05) between them. Not is there between treatments (p = 0.058). ). The graph 6 indicates better result by combining T2 - C. pubescens (0.170 g). The lowest result was seen with T3 - C. pubescens (0.0036 g). • Root Weight

Graph 7: Root weight Plant of C. pubescens and

C. officinalis in the four treatments. T1: Galapagos Inoculum, T2: MUCL41833 Inoculum, T3: Fertilizer, T4: Control. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations. Different letters show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

The species tested showed no significant difference (p = 0.46) between treatments were not (p = 0.73). The graph 7 indicates better result by combining T1 - C. officinalis (0.042 g). The lowest result was seen with T3 - C. pubescens (0.0091 g).

• Air Dry Weight

Graph 8: Air dry weight of plants of C. pubescens and C. officinalis in the four treatments. T1: Galapagos Inoculum, T2: MUCL41833 Inoculum, T3: Fertilizer, T4: Control. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations. Different letters show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

The species tested showed no significant difference (p = 0.60) nor treatment (p = 0.50). The best result was obtained with T2 - C. pubescens

0.000 0.100 0.200 0.300 0.400 0.500

T1 T2 T3 T4

A eri a l Wei gh t ( gr) Treatments

Aerial Weight

C. pubescens C. officinalis a a b b 0 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06 0.07 0.08 0.09T1 T2 T3 T4

R o o t w e ig h t (g ) Treatments

Root weight

C. pubescens C. officinalisa a

a a 0 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06

T1 T2 T3 T4

A ir d ry w e ig h t (g ) Treatments Air dry weight

(0.021 g) and C. officinalis (0.019 g). The lowest result was seen with T3 - C. pubescens (0.0006 g). (Graph 8)

• Root Dry weight

Graph 9: Root dry weight of plants of C. pubescens and C. officinalis in the four treatments. T1: Galapagos Inoculum, T2: MUCL41833 Inoculum, T3: Fertilizer, T4:Control. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations. Different letters show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

The species tested showed no significant difference (p = 0.47) each, or between treatments (p = 0.10).The graph 9, indicates better result by combining T2 - C. pubescens (0.0059 g). The lowest result was seen with T3 - C. pubescens

(0.0001 g).

The literature mentions that the presence of AMF increase biomass, since the plant's vascular system becomes more and rapid availability of nutrients, accelerating their photosynthetic activity thus can maintain its physiological equilibirio increased biomass production. (Alinhhoff, et al.

2009).

We were able to realize that the parameters evaluated were significantly higher in mycorrhizal plants than in the non-mycorrhizal. Smith, et al. (2004), explains that the formation and function of AMF isolates varies between different species and even between isolates of the same species. Therefore, our results support the fact that some plants inoculated with MUCL41833 inoculum or Galapagos showed better responses in growth parameters raised with respect to the other

treatments. Although statistical analysis showed a "no significance" between treatments, we can see a better effect on mycorrhizal plants over non-mycorrhizal in the greenhouse.

PERCENTAGE OF COLONIZATION ASSESSMENT

After discussing the roots stained mycorrhizal structures could be found who reported colonization. Some of the observed structures are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3: a). Arbuscules, b) c). Colonizing the root vesicles, d). Hyphae, structures found in both plant species Cinchona, evaluated after three months of inoculation.

Statistical analysis of the percentage of colonization:

For the statistical analysis of the percentaje of colonization, we considered only the data of T1 and T2, because the other two did not reveal any mycorrhizal colonization.

Frequency of mycorrhization F%:

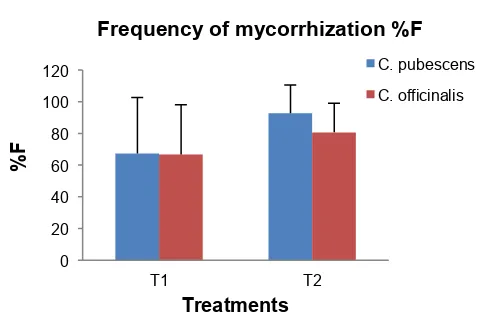

Graph 10: Percentage of Frequency of mycorrhization %F in C. pubescens and C. officinalis plantas with treatments: T1: Galapagos Inoculum, T2: MUCL41833 Inoculum. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations.

0 0.002 0.004 0.006 0.008 0.01 0.012 0.014 0.016

T1 T2 T3 T4

Ro o t d ry w e ig h t (g ) Treatments

Root dry weight

C. pubescens C. officinalis 0 20 40 60 80 100 120

T1 T2

%F

Treatments

Frequency of mycorrhization %F

[image:19.612.321.562.517.675.2]

Percentage in the Frequency of mycorrhization % F no statistical significance between species (p = 0.60), whereas if there was between treatments (p = 0.0509). Better results were obtained with T2 (MUCL41833). in both species, C. pubescens with an average of 92.64 % F, and C. officinalis with a 80.72 %F. The T1 is observed that both species responded to a lesser percentage than T2. Since their % F was 66.76 and 67.22 in C. officinalis and

C. pubescens respectively. (Graph 10).

Arbuscular abundance in the root system A%:

Graph 11: Arbuscular Abundace in the root system %A of C. pubescens and C. officinalis plants in treatmenst: T1: Galapagos Inoculum, T2: MUCL41833 Inoculum. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations.

It was determined that the percentage of abundance Arbuscular %A was statistically significant between species (p <0.0001) and between treatments (p <0.0001). The best results were obtained with T2 (MUCL41833) and C. pubescens with an average of% A 12.28. In other results was negligible presence of arbuscules. (Graph 11).

The arbuscules have a very short life span, when it dies is replaced by a younger provided that the exchange of nutrients is active. When this stops the arbuscules die and there are only internal colonization vesicles (Rocha, et al. 2009). When viewed under a microscope that was founded, because in both species the presence of vesicles was abundant.

The benefits of early inoculation with AMF contribute to improving the adaptability of plants. Plenchette, et al. (1983),describes the benefits of AMF are: nutrition and increased plant growth, increased defense against pathogens and ability to overcome situations of biotic and abiotic stresses. This was evident with both T1 and T2, where the mortality rate was lower and growth was higher in relation to the other two treatments T3 and T4.

Native species of AMF isolated from soil C. pubescens in the Galapagos Islands, showed a high infectivity for both species, making sure that the fungal material is useful. According to Hass and Krikum (1985), it is important to note that an inoculum with roots colonized as infective propagules is of excellent quality as long as you use immediately, because without the living plant, the mycelium colonizing dies in a few weeks still stored under freezing conditions..

Solis, et al. (2009), revealed that placed in direct contact the root system of the plant fungal propagules allows for faster colonization of the root. When the inoculation began the roots of C. pubescens had more size and better root system than C. officinalis, allowing more contact with the inoculum seeing reflected in the higher percentage of colonization obtained.

On the other hand the successful invasion of quinine (Cinchona pubescens) in the Galapagos Islands may be provided by native mycorrhizae (Schmidt and Scow, 1986), which make than an exotic species makes became more competitive than natives ones.

In terms of species Cinchona officinalis, is answered positively with both AM inocula. The beneficial effects of the artificial introduction of a mycorrhizal inoculum are more evident in soils where native AMF populations do not exist or have been eliminated by use of unfavorable agricultural practices for their development as soil fumigation and intensive cultivation (Rivera, et al. 1997). We know that more research is needed to explain the benefits that Cinchona plant with AMF inoculation, the results of this study suggest that 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22

T1 T2

%A

Treatments

Arbuscular Abundance %A

C. pubescens

these fungi could be used as an agricultural management strategy to improve the growth of this species in danger of extinction. This will be promoting sustainable agriculture and minimizing dependence on agricultural inputs, especially chemical fertilizers with the consequent reduction in environmental damage.

In vitro culture of AMF:

AMF spore culture:

Of the 50 Scutellospora savanicola spores that were disinfected to germinate on MSR medium, only 15 showed successful germination at two weeks. This is where contact was established hypha germinating spores of S. savanicola in

Medicago truncatula roots transformed.

[image:21.612.320.553.152.249.2]The evaluation of the presence of S. savanicola in the epidermal cells of the roots was made with the help of a stereoscope. After 42 days of inoculation, we could not see a typical colonization intrarradical, more if we could detect a marked and localized development of hyphae in the culture medium, which spread in a radius of 2-3 cm from the spore inoculated. (Figure. 4)

Figure 4: Germination of Scutellospora savanicola about MSR medium.

AMF roots culture in vitro:

The cultivation of root segments infected with

Glomus sp, gave no tangible result, after growing segments for more than a month on MSR medium, they showed no positive germination. (Fig. 5)

[image:21.612.76.306.443.635.2]

Figure 5:a) Growing AMF colonized roots in the MSR medium

b) Germination root segment, notice how no germination occurs even after and 40 days of incubation

It is not yet clear whether the major differences occur at higher taxonomic levels (genus, suborder). (INVAM, 1993). To date, the literature mentions that only 8% of the known species are used in this type of culture in vitro for the rest not yet know the conditions in which they develop (Cranenbrouck, et al. 2005).

Abbott, et al. (1994) showed that mycorrhizal root segments functioned as effective propagules

Glomus and Acaulospora but not for isolates of

Scutellospora. Likewise, Brundrett, et al. (1999), determined that the spores were useful for the establishment of most species of Acaulospora, Gigaspora and Scutellospora, while presenting little success with root fragments.

Germination time should also be considered for such crops as for raicesgeneralmente fragments is between 2-15 days (Declerck, et al. 2001), but in our assessment that did not happen, since before being placed in the middle crop colonization were not found, which could be a cause of failure of this trial.

Another key factor as Becard and Fortin, (1998), is to get the nutrients necessary for the establishment of AMF and also indicates that some sugars such as sucrose may be inhibitory to mycorrhizal colonization. The above could be one of the causes of the colonization of roots transformed spores of M. truncatula was not favored, since our medium containing sucrose MSR.

Finally we believe that the species should be considered root transformed to be used, since transformed carrot roots are categorized as one of the most suitable species to date for the cultivation of AMF, due to its ease of propagation and maintenance (Declerck, et al. 2001).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We’d like to thank CBCM Centro de Biología Celular y Molecular for their financial support and all the whole team working within the Area of Mycorrhizae, especially to Ing. Hernán Lucero and Ing. Paul Loján for their invaluable assistance on the project.

REFERENCES

ABBOTT L., ROBSON A., GAZEY C., (1994). Selection of inoculant vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. In: NORRIS J., READ D., VARMA A., (eds). Techniques for mycorrhizal research. Academic. San Diego. ALINHOFF C., CACERES A., LUGO L., (2009), Cambios en la biomasa de raíces y micorrizas arbusculares en cultivos itinerantes del Amazonas Venezolano. INCI, 34(8):571-576.

BÉCARD G. and FORTIN J., (1988). Early events of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza formation on Ri T-DNA transformed roots. New phytologist 108: 211-218 BRUNDRETT M., BOUGHER N., DELL B., GROVE T.,, MALAJCZUK N., (1996). Working with mycorrhiza in forestry and agriculture, first edition, Aciar Moniograph publisher, Australia, 185 pp.

CASTILLO R., SOTOMAYOR L., ORTIZ O., BORIE F., RUBIO R., (2009). Effect of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on an Ecological Crop of Chili Peppers (Capsicum annuum L.), Chilean J. Agric. Res, .69:79-87

CRANENBROUCK S., VOETS L., BIVORT C., RENARD L., DECLERCK S., (2005). Methodologies for in Vitro Cultivation Of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi With Root Organs, In: DECLERCK S., STRULLU S., Fortin J., (Eds.), In Vitro Culture of Mycorrhizas, Belgium, 396 pp.

DE SOUZA F., DECLERCK S., (2003). Mycelium development and architecture, and spore production of Scutellospora reticulata in monoxenic culture with Ri T-DNA transformed carrot roots, Mycologia, 95(6):1004– 1012.

DECLERCK S., CRANENBROUCK S., LE BOULENGÉ E., (2001). Modeling the sporulation dynamics of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in monoxenic culture. Mycorrhiza 11:225–230

GEDERMANN J., NICOLSON H., (1963). Spore of micorrhizal endogone species extracted from soil by wet sieving and decanting. Transactions of the Brithish of Mycological society. 46:235-244.

GONZÁLEZ C., MONROY A., GARCÍA E., OROZCO M., (2005). Influencia de hongos micorrizógenos arbusculares (hma) en el desarrollo de plántulas de Opuntia streptacantha Lem. sometidas a sequía en condiciones de invernadero , Revista Especializada en Ciencias Químico-Biológicas, 8(1):5-10.

HARRISON J., (1997). The arbuscular mycorrhizal simbiosis: AN underground association. Review Elsevier Trends Journal, 2(2): 54-60

HASS J., KRIKUM J., (1985). Efficacy of endomycorrhizal-fungus isolates and inoculums quantities required for growth response. New Phytol. 100(4): 613-621

HERNÁNDEZ M. and CHIALLOUX M., (2001). La nutrición mineral y la biofertilización en el cultivo del tomate (Licopersicon esculentum Mill). Temas de Ciencia y Tecnología. 5 (13):11

HOLGUIN G., BASHAN Y., FERRERA-CERRATO R., (1996), Interactions between Plants and Beneficial Microorganims. Ed. Terra, 14:2

International Culture Collection of Arbuscular & Vesicular- Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (INVAM), searched 2011, http: www.invam.caf.wvu.edu.

LOAIZA T., SÁNCHEZ E., (2006). La corteza de Loja, Revista Ecuador Tierra Incógnita, ECU-10:1-4

MATÍNEZ V., López M., DIBUT-ÁLVAREZ B., PARRA Z. y RODRÍGUEZ J., (2007). La fijación biológica de nitrógeno atmosférico en condiciones tropicales. Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Agricultura. 172 p. MORTON J., BENNY G., (1990). Revised classification of Arbuscular mycorhizal fungi (Zygomycetes): a new order, Glomales, two new suborders, Glominae and Gigasporineae, ando two familes, Acaulosporaceae and Gigasporaceae, with an emendation of Glomaceae, Mycotaxon, 37:471-491.

PHILLPS J. and HAYMAN D., (1970). Improve procedure for clearing roots and stainin parasitic and vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid asesment of infection. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 55: 158-161.

PLENCHETTE C., (2000). Receptiveness of some tropical soils from banana fields in Martinique to the arbuscular fungus Glomus intraradices. Appl. Soil Ecol. 15: 253-260.

READ D., (1999), Mycorhiza: the state of the art., Second Edition. Varma & Hock Publisher. Berlin, pp 3-34.

RIVERA R., FERNÁNDEZ F., SÁNCHEZ C., BUSTAMANTE C., HERRERA R. y OCHOA M., (1997). Efecto de la inoculación con hongos Micorrizógenos VA y bacterias rizosféricas sobre el crecimiento de posturas de cafeto (Coffeea arabica L.) Cultivos Tropicales 18 (3). 15-23

ROCHA L., RAMOS C., ROSALES C., (2009), Multiplicación de Hongos Micorrízicos arbusculares MA nativos de cultivos de cacao (Theobroma cacao), en Maiz (Zea mays), bajo distintos tratamientos agronómicos, Tesis- Universidad Popular del Cesar, Valledupar.

SCHMIDT S. and SCOW K., (1986). Mycorrhizal fungi on the Galapagos Islands. Biotropica, 18, 236-240. SILVA F., (1999). Manual de análisis químicos de suelos, plantas y fertilizantes, Embrapa informática Agropecuaria, Brasilia, 370pp.

SMITH S., SMITH F., JAKOBSEN I., (2004). Functional diversity in arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbioses: the contribution of the mycorrhizal P uptake pathway is not correlated with mycorrhizal responses in growth or total P uptake. New Phytol 162:511-524.

SMITH S., READ D., (1997). Mycorrhizal Symbiosis., 2da edición, Academic Press publisher , London. 605 pp.

SOLIS G., CARDENAS F., (2009) Efecto de los hongos micorrisógenos arbusculares (glomus fasciculatum) en el crecimiento y desarrollo del cultivo de tomate de

mesa (solanum lycopersicum) variedades alambra y fortuna en la zona urcuquí provincia de imbabura. Tesis Doctoral.

ABREVIATURAS

Nomenclatura

Hongo Micorrízico Arbuscular HMA

Micorriza Arbuscular MA

Hifas hif.

Vesículas ves.

Arbúsculos arb.

Tratamiento: Inóculo de Galápagos T1

Tratamiento: Inóculo MUCL41883 T2

Tratamiento: Fertilizante T3

FIN, PROPÓSITO Y COMPONENTES DEL PROYECTO

Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja

FIN, PROPÓSITO Y COMPONENTES DEL PROYECTO

Fin del Proyecto (objetivos de desarrollo):

Dilucidar el efecto de las comunidades de HMA asociados a C. pubescens

provenientes de la isla de Santa Cruz – Galápagos sobre el crecimiento de plántulas

de C. pubescens y officinalis en etapa de vivero.

Aportar información para desarrollar, utilizar y aplicar técnicas y/o métodos para el aislamiento de HMA con el fin de incentivar su uso en el campo agrícola como

biofertilizantes de primera elección.

Propósito del Proyecto (objetivo inmediato)

Aislar HMA (Hongos Micorrízico arbusculares) que se encuentren asociados a

Cinchona pubescens de Isla Santa Cruz, Galápagos.

Determinar los porcentajes de colonización por HMA, probadas en plantas de

Cinchona pubescens y officinalis en Loja.

Fortalecer los estudios ya realizados en la Universidad, dentro del CBCM en el campo de las micorrizas.

Componentes del Proyecto (productos)

Con este estudio, y en base a nuestros objetivos propuestos esperamos obtener:

Cultivos de HMA asociados a C. pubescens provenientes de la Isla Santa Cruz,

Galápagos.

Multiplicación de HMA en plantas hospederas micotróficas de Loliumperenne.

Mejorar el crecimiento y supervivencia de las plantas micorrizadas de Cinchona, con respecto a sus homólogas en cuanto a la masa seca total, el número de tallos, la tasa

INTRODUCCIÓN Y ANTECEDENTES

Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja

1.

INTRODUCCIÓN Y ANTECEDENTES:

1.1 MICORRIZAS:

1.1.1 Definición:

El término micorriza proviene del griego: myco, (hongo), y rhyza, (raíz), este término fue

acuñado por A.B. Frank en 1885, para describir las asociaciones simbióticas entre raíces

vegetales y hongos del suelo.1 Casi todas las especies vegetales son susceptibles de formar

simbiosis con micorrizas porque estas se encuentran en la mayoría de los hábitats naturales,

(más del 90% de todas las especies vegetales conocidas presentan al menos un tipo de

micorriza).2

Algunos de los beneficios que obtiene la planta con esta asociación son en el aumento del

crecimiento aéreo y radicular gracias a la mayor absorción de nutrientes del suelo,

especialmente de aquellos poco móviles como por ejemplo el fósforo, magnesio, calcio,

potasio, azufre, hierro, cobre, boro y manganeso;3 además debido al mayor volumen de suelo

explorado por las hifas, se incrementa la captación de agua a la planta, mejorando la

tolerancia al estrés hídrico.4

La diversidad funcional de los hongos micorrízicos provee la oportunidad de seleccionar un

hongo adaptado específicamente al hospedero, medio ambiente y condiciones de suelo que

optimiza el crecimiento de las plantaciones.5

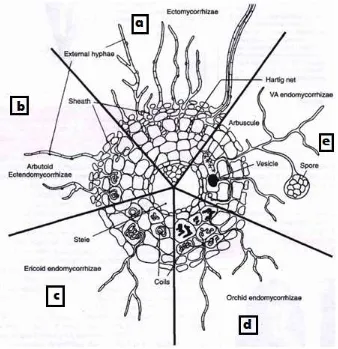

1.1.2 Clasificación Morfológica de Micorrizas:

Se pueden distinguir tres grupos fundamentales según la estructura de la micorriza formada6:

1 FRANK A. B., (1885), On the root symbiosis depending nutrition through hypogeous fungi of certain trees. Proc. Amer. Conf. Myc, 6:18-25. 2 HERNÁNDEZ M., (2000), Las micorrizas arbusculares y las bacterias rizósfericas como complemento de la nutrición mineral de tomate (lycospersicon esculentm mill), Tesis de Maestría, Inca.

3 HOLGUIN G., BASHAN Y., FERRERA-CERRATO R., (1996), Interactions between Plants and Beneficial Microorganims. Ed. Terra, 14:2 4 SMITH S., READ D., (1997). Mycorrhizal Symbiosis., 2da edición, Academic Press publisher , London. 605 pp.

5 BRUNDRETT M., BOUGHER N., DELL B., GROVE T.,, MALAJCZUK N., (1996) Working with mycorrhiza in forestry and agriculture, first edition, Aciar Moniographpublisher, Australia, 185 pp.

INTRODUCCIÓN Y ANTECEDENTES

Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja

Ectomicorrizas: Este grupo de micorrizas se caracteriza por tener un manto compacto de

hifas que cubre las raíces cortas con una red micelial, la cual crece entre las células corticales

por lo que se la conoce como Red de Harting.7 (Fig. 1a).

Ectendomicorriza: Tienen características intermedias entre las Ectomicorrizas y las

Endomicorrizas, 6 pues presentan un manto muy reducido pero la red de Harting está bien

desarrollada, además existe una ligera penetración de las hifas al interior de las células de la

corteza radical, no existen vesículas ni arbúsculos.8 (Fig. 1b)

Endomicorrizas: Este grupo se caracteriza por no formar manto y las hifas penetran en las

células de la epidermis y del córtex de la raíz.9 Por lo que una especie puede infectar a un

gran número de especies vegetales, lo que las hace poco específicas. Son mucho menos

sensibles a las agresiones externas que las ectomicorrizas debido a que sus esporas

germinan con facilidad alejadas de raíces vivas y pueden crecer considerablemente sin

contacto con ninguna raíz10. Este grupo se subdivide en:

Ericoides: estos hongos carecen de vesículas y arbúsculos, sin embargo cuentan con

estructuras intracelulares las cuales semejan a espirales que son estructuras típicas de

estos hongos.8 (Fig. 1c)

Orquidoides: Son micorrizas de orquídeas, tras penetrar en la células de la raíz forma

ovillos dentro de la célula hospedera, así como agregados poco organizados de hifas

(pelotones) que liberan los nutrientes cuando degeneran.5 (Fig. 1d)

Arbusculares: Se caracterizan por la penetración de las hifas del hongo en las células

de la epidermis y córtex de la raíz y por la ausencia de manto sobre la superficie de la

misma 5. (Fig. 1e)

7 FERRERA-CERRATO R., GONZÁLEZ-CHÁVEZ M., (1998). La simbiosis micorrízica en el manejo de vivero de los cítricos. Textos Universitarios, Universidad Veracruzana, México pp. 37-63.

8YU T., EGGER K.,, PETERSON R., (2001), Ectendomycorrhizal associations characteristics and functions, Mycorrhiza 11: 167-177.

9 GONZÁLEZ C., MONROY A., GARCÍA E., OROZCO M., (2005) Influencia de hongos micorrizógenos arbusculares (hma) en el desarrollo de plántulas de Opuntia streptacantha Lem. sometidas a sequía en condiciones de invernadero , Revista Especializada en Ciencias Químico-Biológicas, 8(1):5-10,

INTRODUCCIÓN Y ANTECEDENTES

Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja

Fig. 1. Principales estructuras de los tipos de micorrizas (Figura tomada de Selosse y Le Tacon F. 1998)11

1.2 MICORRIZAS ARBUSCULARES

1.2.1 Descripción de los HMA

Los hongos micorrízicos arbusculares se asocian con las raíces de la mayoría de las especies

vegetales y les proporcionan múltiples beneficios: mayor captación de nutrientes, resistencia a

las condiciones de estrés provocadas por patógenos de hábitos radicales, salinidad, sequía,

acidez y elementos tóxicos.3 También son responsables de influenciar en la diversidad vegetal

y la productividad en ecosistemas naturales.12 Estos hongos presentan un crecimiento intra e

11 SELOSSE M., LE TACON F., (1998), The land flora: a phototroph fugus partnership, Tree, 13 (1): 15-20

[image:28.612.133.471.120.469.2]INTRODUCCIÓN Y ANTECEDENTES

Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja

intercelular en la corteza de la raíz de la planta, una característica específica es la formación

de estructuras intraradicales denominadas arbúsculos que consisten en ramificaciones

dicotómicas repetidas de un hifa, hasta dar una estructura similar a un árbol muy ramificado

(Fig. 2). Los HMA son simbiontes obligados, de esta manera, esta simbiosis permite a las

plantas captar fotosintatos que favorecen su desarrollo y propagación.

Fig. 2: Representación de un hongo Micorrízico Arbuscular: (Figura tomada de Moore-Landecker B. 1996)13

1.2.2 Arquitectura de la micorriza Arbuscular

1.2.2.1 Hifas

Las hifas son estructuras filamentosas que en conjunto forman un micelio.

Existen tres tipos de hifas: las intercelulares, intracelulares y las extraradicales.

1.2.2.1.1 Hifas intercelulares:

Son aquellas que crecen dentro de la pared de las células de la raíz (Fig. 3a).

1.2.2.1.2 Hifas intracelular:

Son aquellas que crecen entre la pared de las células de la raíz (Fig. 3b.)

1.2.2.1.3 Hifas extraradicular: (Fig. 3c.)

[image:29.612.199.446.232.466.2]

INTRODUCCIÓN Y ANTECEDENTES

Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja

Este tipo de hifas se clasifican en tres subtipos según su morfología y las funciones que

llevan a cabo: hifas infectivas, son las que inician los puntos de colonización en una o

varias raíces; hifas absorbentes son las que se encargan de explorar el suelo para la

extracción de nutrientes y las hifas fértiles son las que llevan las esporas.14

1.2.2.2. Apresorios

Son apéndices, que se forman cuando una hifa hace contacto con la superficie de una célula

epidérmica de la raíz15, esta estructura facilita la penetración del hongo.16 (Fig. 3d.)

1.2.2.3. Vesículas

Son órganos de paredes delgadas que almacenan lípidos y glicolípidos se forman a partir del

hinchamiento de una hifa terminal.3 Las vesículas pueden ser inter o intracelulares y pueden

ser encontradas tanto en el interior como en las capas externas del parénquima cortical. Estas

no están presentes en todos los géneros de HMA.17 (Fig. 3e.)

1.2.2.4 Arbúsculos

Son minúsculas ramificaciones dicotómicas, sirven como sitio de intercambio nutrimental

entre el hongo y el hospedero. Son de corta duración 9 a 15 días, al cabo de lo cual colapsan

o son digeridos por la célula hospedera, después de un gran período de actividad

metabólica.18 (Fig. 3f.)

1.2.2.5. Células auxiliares

Son estructuras abultadas de paredes delgadas, que se agrupan en las hifas extraradicales.

Puede presentar una superficie espinosa o lisa y son característicos de Scutellospora y

Gigaspora, son abundantes durante la colonización temprana, pero disminuyen durante la

esporulación. Al parecer no funcionan como propágulos.19

14 GUZMÁN S., FARÍAS J., (2005), Biología y regulación molecular de la micorriza Arbuscular, Avances en Investigación Agropecuaria, 9:17-31.

15 LEON D., (2006), Evaluación y Caracterización de Micorrizas Arbusculares asociadas a Yuca (Manihot esculenta sp) en dos regiones de la amazonia colombiana. Trabajo de tesis para el titulo de microbiólogo, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá.

16 GARCIA J., OCAMPO J., (2002), Regulation of the plant defence response in arbuscular mycorrhizal simbiosis, J.Exp. Bot., 53:1377-1386 17 MOSSE B., (1981). Vesicular micorrizas arbusculares, Investigación de Agricultura Tropical, Universidad de Hawai, Hawai.

18 REQUENA N., (1996), Exploración de la biodiversidad microbiana (hongos de las micorrizas arbuscula-Rhizobium-Rizobacterias) en un ecosistema mediterráneo desertificado dirigida a una estrategia de revegetación, Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Granada.

INTRODUCCIÓN Y ANTECEDENTES

Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja

[image:31.612.103.508.111.393.2]

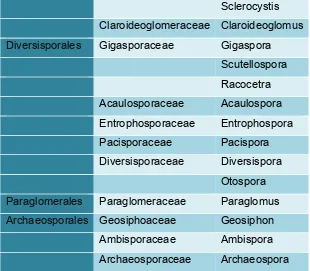

Fig. 3.: Estructura de los Hongos Micorrízicos Arbusculares (Figura tomada de Chung, P. 2005) 1.2.3 Clasificación de los HMA

Tradicionalmente la espora ha sido la estructura más usada para la identificación de HMA en

los primeros estudios de taxonomía. Actualmente se han venido usando estudios moleculares

para el esclarecimiento de las relaciones filogenéticas entre hongos, que revela un gran

número de nuevas especies.4

En la siguiente tabla se detalla la clasificación más actualizada:

Phylum: Glomeromycota

Class: Glomeromyces

Orden Familia Genero

Glomerales Glomeraceae Glomus

Funneliformis

INTRODUCCIÓN Y ANTECEDENTES

Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja

Sclerocystis

Claroideoglomeraceae Claroideoglomus

Diversisporales Gigasporaceae Gigaspora

Scutellospora

Racocetra

Acaulosporaceae Acaulospora

Entrophosporaceae Entrophospora

Pacisporaceae Pacispora

Diversisporaceae Diversispora

Otospora

Paraglomerales Paraglomeraceae Paraglomus

Archaeosporales Geosiphoaceae Geosiphon

Ambisporaceae Ambispora

[image:32.612.148.458.122.393.2]Archaeosporaceae Archaeospora

Tabla 1: Clasificación de los hongos micorrizicos arbusculares (en base a la clasificación de Schüßler and Walker 2010)

1.3 SIMBIOSIS HMA-PLANTA HOSPEDERA

1.3.1 Multiplicación de inóculo Micorrízico:

El carácter de simbionte obligado de los HMA conlleva al uso de plantas hospederas para que

pueda completar su ciclo de vida.20

Los ecosistemas naturales ofrecen comunidades de hongos micorrízicos nativos que

frecuentemente son usados como fuente de inóculo. Estos propágulos fúngicos están

constituidos por trozos de raíces colonizadas, esporas y segmentos de hifas que por lo

general se encuentran concentrados en los primeros centímetros del suelo.21

20 USUGA C., CASTAÑEDA D., FRANCO A., (2008) Multiplicación de hongos micorriza arbuscular (H.M.A) y efecto de la micorrización en plantas micropropagadas de banano, Revista Facultad Nacional de Agronomía 61:4279-4290.

INTRODUCCIÓN Y ANTECEDENTES

Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja

Las muestras de suelo generalmente son tomadas de porciones cercanas a la raíz, éstas,

pueden contener diferentes tipos de propágulos, pero son las esporas que por sus

características morfológicas permiten la identificación de las especies.5 Sin embargo las

esporas provenientes de estas porciones de suelo pueden no estar en buenas condiciones

para su identificación, por lo que el inóculo tiene que multiplicarse en plantas hospederas

micotróficas cultivadas en sustratos o suelo estéril. Este sistema conocido como cultivo

trampa permite multiplicar las especies nativas colectadas del campo.22

No todas las asociaciones entre HMA-planta son compatibles, pudiendo en algunos casos

beneficiar en mayor grado a un hospedero y adaptarse a determinadas condiciones

edafoclimáticas evidenciando marcadas diferencias no sólo estructurales sino también

funcionales entre especies.23

1.3.2 Plantas hospederas:

Se ha demostrado que la asociación de HMA y plantas no es específica, puesto que

cualquiera de los HMA puede colonizar a cualquiera de las plantas susceptibles de formar

simbiosis.5 Algunos hongos muestran un mejor grado de efectividad que beneficia el

establecimiento de la micorriza bajo determinadas condiciones.24

Las principales condiciones que se deben tomar en cuenta para la elección de una panta

hospedera óptima son: ser micótrofa obligada y no selectiva a las diferentes especies de

hongos micorrízicos arbusculares; adaptarse a un rango amplio de condiciones de suelo y

clima; rústica para que su mantenimiento no requiera mucho espacio ni cuidados en el

invernadero o en condiciones de vivero; con semillas con un alto porcentaje de germinación;

no debe tener enfermedades radicales en común con los cultivos en los cuales se utilizara el

inoculo.23

22 SIEVERDING E., (1991) Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza management in tropical agrosystems, Academic Press, Great Britain 605pp. 23 LINDERMAN R., DAVIS E., (2004), Varied response of marigold (Tagetes spp.) genotypes to inoculation with different arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Sci. Hort. 99:67-78