Availableonlineatwww.sciencedirect.com

Revista

Mexicana

de

Biodiversidad

www.ib.unam.mx/revista/ RevistaMexicanadeBiodiversidad87(2016)18–28

Taxonomy

and

systematics

Assessment

of

non-cultured

aquatic

fungal

diversity

from

different

habitats

in

Mexico

Estimación

de

la

diversidad

de

hongos

acuáticos

no-cultivables

de

diferentes

hábitats

en

México

Brenda

Valderrama

a,

Guadalupe

Paredes-Valdez

a,

Rocío

Rodríguez

b,

Cynthia

Romero-Guido

b,

Fernando

Martínez

b,

Julio

Martínez-Romero

c,

Saúl

Guerrero-Galván

d,

Alberto

Mendoza-Herrera

e,

Jorge

Luis

Folch-Mallol

b,∗aInstitutodeBiotecnología,UniversidadNacionalAutónomadeMéxico,AvenidaUniversidad2001,Col.Chamilpa,62210Cuernavaca,Morelos,Mexico bCentrodeInvestigaciónenBiotecnología,UniversidadAutónomadelEstadodeMorelos,AvenidaUniversidad1001,Col.Chamilpa,62209Cuernavaca,

Morelos,Mexico

cCentrodeCienciasGenómicas,UniversidadNacionalAutónomadeMéxico,AvenidaUniversidads/n,Col.Chamilpa,62210Cuernavaca,Morelos,Mexico dCentroUniversitariodelaCosta,UniversidaddeGuadalajara,AvenidaUniversidad203,DelegaciónIxtapa,48280PuertoVallarta,Jalisco,Mexico eCentrodeBiotecnologíaGenómica,InstitutoPolitécnicoNacional,BoulevarddelMaestros/nesq.ElíasPi˜na,Col.NarcisoMendoza,88710Reynosa,

Tamaulipas,Mexico

Received20August2013;accepted27September2015 Availableonline28February2016

Abstract

WiththeaimtoexplorethediversityofaquaticfungiinMexicowepresentaninvestigationusingafragmentofthe18SribosomalDNAas amolecularmarkerobtainedfromdifferentwaterbodies(marine,brackishandfreshwater).RibosomalgenefragmentswereobtainedbyDNA amplification,theresultingsequenceswerecomparedusingmultiplealignmentsagainstacollectionofclassifiedreferencefungalsequencesand thensubjectedtophylogeneticclusteringallowingtheidentificationandclassificationofDNAsequencesfromenvironmentalisolatesasfungal downtothefamilylevel,providedenoughreferencesequencewereavailable.Fromourensembleof2,020sequencesidentifiedasfungal,23.8% wereclassifiedatthefamilylevel,48.5%attheorderlevel,13%attheclass/subphylumleveland14.7%ofthesequences(allfromthesame site)couldnotbeunambiguouslypositionedinanyofourreferencefungalgroupsbutwerecloselyrelatedtouncultivatedmarinefungi.The mostfrequentlyrecoveredphylumwasAscomycota(89.1%),followedbyChytridiomycota(8.1%),Basidiomycota(2.8%)andMucoromycotina (1.3%).

AllRightsReserved©2015UniversidadNacionalAutónomadeMéxico,InstitutodeBiología.Thisisanopenaccessitemdistributedunderthe CreativeCommonsCCLicenseBY-NC-ND4.0.

Keywords: Aquatichabitats;Fungi;Taxonomicclassification;Fungalpopulations;18SribosomalDNA

Resumen

Con lafinalidad deexplorarladiversidad dehongosacuáticosen México,se presentauna investigaciónusando unfragmento del ADN ribosomal18Scomounmarcadormolecularobtenidodemuestrasdecuerposacuáticoscondiferentescaracterísticas(marino,salobreydulce). LosfragmentosdelosgenesribosomalesseobtuvieronmediantelaamplificacióndeADN,lassecuenciasresultantessecompararonmediante alineamientosmúltiplesconunaseleccióndesecuenciasdehongoscomoreferenciayposteriormenteseanalizaronfilogenéticamente,permitiendo laidentificaciónyclasificacióndesecuenciasdeADNprovenientesdeaisladosambientaleshastalacategoríadefamilia,cuandohubosuficientes secuenciasdisponibles.Delas2,020secuenciasidentificadascomohongos,un23.8%seclasificaroncomofamilia,un48.5%comoorden,un13%

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:jordi@uaem.mx(J.L.Folch-Mallol).

PeerReviewundertheresponsibilityofUniversidadNacionalAutónomadeMéxico.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2016.01.013

comoclase/subphylumyun14.7%delassecuencias(todasdelmismolugar)nopudieronsercolocadasinequívocamenteenalgunodelosgrupos dehongosquesetomaroncomoreferencia,peroseencontraronmuycercanamenterelacionadasahongosmarinosnocultivables.Elphylummás representadofueAscomycota(89.1%),seguidodeChytridiomycota(8.1%),Basidiomycota(2.8%)yMucoromycotina(1.3%).

DerechosReservados©2015UniversidadNacionalAutónomadeMéxico,InstitutodeBiología.Esteesunartículodeaccesoabiertodistribuido bajolostérminosdelaLicenciaCreativeCommonsCCBY-NC-ND4.0.

Palabrasclave: Hábitatsacuáticos;Hongos;Clasificacióntaxonómica;Poblacionesfúngicas;ADNribosomal18S

Introduction

Currentestimatesoffungaldiversitybasedontheplant:fungi ratio found in countries where both populations are suffi-cientlywellstudiedsuggesttheexistenceof1.5millionspecies (Hawksworth,1991,2001;Mueller&Schmit,2007).Thestudy offungaldiversityisimportantbecausefungiaredecomposers oforganicmatterandcompriseamajorproportionofmicrobial biomass.Recently,globalclimatechangeandthebetterknown roleoffungiinbiogeochemicalcycleshaveenforcedthe impor-tanceofstudyingfungaldiversity(Chapinetal.,2000;Wardle &Giller,1996).

Studiesoffungaldiversityhavebeenlimitedbythelackof appropriatemicrobiologicalmethods(Kimura,2006;Torsvik& Ovreas,2002).The applicationof molecularapproachessuch asextracting,cloningandamplifyingDNAfromenvironmental samplescurrentlyallowsustoexplorebiodiversitywithoutthe needofculturing.Inthisregard,18SribosomalDNA(rDNA) sequenceshavebeenextensivelyusedtoexplorefungal diver-sity (Hunt, Boddy, Randerson, & Rogers, 2004; Le Calvez, Burgaud,Mahé,Barbier,&Vandenkoornhuyse,2009;Monchy etal.,2011;Piquet,Bolhuis,Meredith,&Buma,2011)andmany specificprimershavebeendesignedforthispurpose(Borneman &Hartin,2000;Moon-vander Staay,De Wachter,&Vaulot, 2001;Vainio&Hantula,2000).Thecapacityoftheseprimers to reveal fungal diversity in environmental samples is based ontheirspecificityinpreferentiallypriming fungalsequences andalsotheirabilitytorepresentallfungalphylaatthe same time(Anderson,Campbell,&Prosser,2003;Huntetal.,2004). Moleculartools,including18SrDNAsequenceanalysis,have beenusedrecentlytore-definefungaltaxonomybasedon multi-locusphylogeneticanalyses(Hibbettetal.,2007;Jamesetal., 2006).Asaconsequence,ourviewoftraditionalfungalgroups haschangeddrastically.

Ifterrestrialfungiare stilllargelyunder-described,aquatic fungiareevenlesswellknown.Mostofthecultivatedaquatic speciesbelongtotheChytridiomycotaandAscomycotaphyla (Mueller & Schmit, 2007; Mueller, Bills, & Foster, 2004; Sheareretal.,2007)andmanyfungal-relatedmicrobes belong-ingtothestraminipiles (oomycetesandhyphochytriomycetes inparticular) havebeen described (Mueller etal., 2004; Van der Auwera et al., 1995). In Mexico, an important effort to explorefungaldiversityhasbeenmade(Guzmán,1998). Explo-rationof aquaticfungaldiversity hasalsobeen conductedby traditionalmethodsisolatingfungifromfreshwaterandmarine environments(González&Chavarría,2005;González,Hanlin, Herrera, & Ulloa, 2000; González, Hanlin, & Ulloa, 2001; Heredia,Reyes,Arias,Mena-Portales,&MercadoSierra,2004).

In marine environments, ascomycetes and mitosporic fungi weremainlyfound,althoughonebasidiomycetewasreported (Gonzálezetal.,2001).

To explorethe diversityofaquaticfungiinMexicoandto demonstratethepotentialofaclassificationsystembasedona singlemolecularmarker,wepresentaninvestigationofdifferent waterbodies(marine,brackishandfreshwater)usingafragment of 18S rDNA sequences andthe results of our phylogenetic clusteringapproach.

Materialsandmethods

Descriptionofthesampledlocations

Zempoala, Morelos (fresh water, 19◦0120N, 99◦1620W). The Zempoala Lagoons comprises 7 pris-tine water bodies located in a protectedpark in the state of Morelos at 2670–3686masl. The area is surrounded by a temperateforestofpines,firsandoaks.Sampleswereobtained fromoneofthepermanentlagoons.

Carboneras, Tamaulipas (brackish water, 24◦3741.88N, 97◦4259.19W). Fishery and leisure town located at 58km from San Fernando inthe state of Tamaulipas. It belongs to thecentralsectionofLagunaMadre.

Mezquital, Tamaulipas (sea water, 25◦1455.70N, 97◦3105.54W).Locatedintheeasternsideofthewiderpart ofLagunaMadre,itisconnectedtotheGulfofMexicothrough anartificialnavigationchannel.

Media Luna, Tamaulipas(brackishwater, 25◦0947.64N, 97◦4016.35W).Locatedatthewesternsideofthewiderpart of LagunaMadre,andduetopoor roadconditionsandtothe absenceoflargesettlements,thisisoneofthelessspoiledareas. ThedistancebetweentheMezquitalandMediaLunasampling placesisapproximately12km.

El Rabón, Tamaulipas (hypersaline sea water,

25◦2623.68N, 97◦2434.79W). At the northern end of LagunaMadre, thisareahassufferedserious transformations due to human activity and had become dry. Recently, the wetlandshavebeenrestoredbypumpinginseawater.

Carpintero. Tamaulipas (fresh water, 22◦1401.12N, 97◦5120.67W). Belonging to the Pánuco River basin and located in a protectednatural parkcovering 7ha, Carpintero Lagooniscurrentlyusedforfishandcrocodilebreedinggrounds. InspiteoftheurbanlocationofthesiteintheCityofTampico itisrelativelyunspoiled.

20 B.Valderramaetal./RevistaMexicanadeBiodiversidad87(2016)18–28

abovesealevel.Withanaveragevolumeof500millionm3itis usedforaquaticsportsandsportfishing.

Bahía de Banderas, Jalisco (sea water, 20◦3858.93N, 105◦2451.94W).Locatedintheborderbetweenthestatesof NayaritandJaliscointhePacificCoast,itisthelargestbayin Mexico with asurface of 773km2. The Ameca Rivermouth dividesthebay,whichhasahighpopulationdensitybasedon PuertoVallarta.

Cruz de Huanacaxtle, Nayarit(sea water, 20◦4412.96N, 105◦2317.53W).Acoastalsitewithlowanthropogenicimpact locatedinthe northendofBahía deBanderasinthestate of Nayarit.ThedistancebetweentheBahíadeBanderasandCruz deHuanacaxtlesampledsitesisapproximately15km.

Zacapulco,Chiapas(mangroveswampwater,15◦0407N, 92◦4520W).Unspoiledmangrovearealocated200km north-westof theborderofthe stateofChiapaswithGuatemalaon the PacificOcean coastline.At14masl,theestuarine salinity oscillateswiththetides.Theperennialvegetationprovides cov-erageforthehabitatofmanyaquaticbirds.Thereisnoseasonal daytimechangeandtemperaturesvarybetween25and35◦C.

Santa Catarina, Querétaro (fresh water, 20◦4730.6N, 100◦2701.66W).An artificialwaterreservoirlocated25km northwestofthecityofQuerétarointhestateofQuerétaroat 2035masl.

Samplecollection

We decided to collect samples from water instead from organicmattertorecoverawiderselectionofthefungal popu-lationineachsite,notonlyofthosedirectlyinvolvedindecay. Samples were collected from 0.5m below the water surface using acleanandsurfacesterilizedcontainer.Typicalsample volumeswere20L.Thewholesamplewaspassedthrough3 lay-ersofsterilecheeseclothandafterwardsfilteredthrough5m PVDFmembranes(Millipore).Thebiomasslayerwasscrapped withaspatula fromthe membranes,washedin3–5ml ofthe samewaterandcentrifugedin3differentEppendorftubesfor replica analysis. Final biomass volumes were of 0.1–0.3ml. Pelletswerefrozenat−20◦Cuntilextraction.

DNAextraction

The whole pellet was processed andtotal DNA extracted usingtheUltraCleanSoilDNAKit(MoBio,Carlsbad,USA)in accordancetothemanufacturer’sinstructions.TotalDNAwas analyzedforintegritybyagarosegelelectrophoresis.

RibosomalDNAamplification

TotalDNAaliquotswereamplified usingprimers nu-SSU-0817andnu-SSU-1536(Borneman&Hartin,2000),yieldinga primary product of approximately 750bp.Reaction mixtures contained 2.5mM MgCl2, 1mM dNTPs mix, 5pM of each primer,50ngoftotalDNAastemplate,1Xreactionbufferand 5UofTaqpolymerase(Altaenzymes,Alberta,Canada). Reac-tionmixturesweresubjectedtoaninitialdenaturationstepof 5minat95◦Cfollowedby30amplificationcycles(30sat95◦C,

30sat55◦C,45sat72◦C)andafinalextensionstepof2min at72◦C.AmplificationswereperformedinaPCRsprint ther-malcycler(ThermoElectronCorporation,USA).Theresultant fragments were separated by agarosegel electrophoresis, the amplifiedfragmentwasvisualizedbyethidiumbromide stain-ing,excisedandpurifiedwiththeQIAquickgelextractionkit (QIAGEN,Hilden,Germany).

Libraryconstruction

AmplifiedfragmentsweredirectlyclonedinthepGemT-easy vector(Promega,Madison,USA)andtransformedby electro-poration into Escherichiacoli strain DH5␣.Insert-containing clonesweredetectedbythelackofcolorationinthepresence of X-galandIPTGandpickedinfreshplates.Plasmidsfrom 6 randomly selectedclones from each library were extracted byalkalinelysisandsequencedforinsertverification.Inthose caseswheretheamplificationproductcouldnotbedetectedin atleast4outofthe6clonesorwhenthesequencedinsertswere not offungalribosomalgenes,the procedurewas repeatedto obtainabetteryieldorquality.

DNAsequencing

Agroupof384randomlyselectedclonesfromeachlibrary wassequencedinsetsof496-wellplates.Colonieswerepicked andplasmidDNAextractedbyalkalinelysis.Theconcentration andintegrityofisolatedDNAwereverifiedbyagarosegel elec-trophoresisandsequencedwiththeT7primerintheSequencing UnitoftheCentrodeCienciasGenómicas(UNAM).

Controlexperiments

GenomicDNA ofdifferent organismswasused as control beforesampleamplification.Fromprokaryoticsources:E.coli,

RhizobiummelilotiandSpirulinamaxima.Fromfungalsources:

Aspergillusnidulans,Debaryomyceshansenii,Yarrowia lipoly-tica,Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizophyllumcommune and

Bjerkandera adusta. For an arthropod source we used DNA fromCentruroideslimpidusandfromplantsources,Arabidopsis thalianaandPhaseolusvulgaris.Inallcasesthesampleswere kindlyprovidedbycolleaguesattheInstitutodeBiotecnología (UNAM) and the Centro de Investigación en Biotecnología (UAEM).

Sequenceanalysis

Table1

Taxonomicclassificationofreferencesequencesusedinthiswork.

Phylum Class/Subphylum Order Family Species GI

Ascomycota Saccharomycetes Saccharomycetales Mitosporic Saccharomycetales

CandidasakestrainJCM8894 4586748

Candidafluviatilis 4586709

CandidamembranifaciensstrainW14-3 124494629

Saccharomycetaceae Kazachstaniasinensis 114050511

Kluyveromyceshubeiensis 33114591

Saccharomycescerevisiae 270308944

Eurotiomycetes Onygenales Onygenaceae Castanedomycesaustraliensis 21732245

Mycocaliciales Mycocaliciaceae Chaenothecopsissavonica 2804615

Chaetothyriales Incertaesedis Coniosporiumsp.MA4597 66990818

Eurotiales Trichocomaceae Penicilliumsp.EnrichmentculturecloneNJ-F4 270311611

Aspergillussp.Z3b 151384867

AspergillusunguisstrainF3000054 120431388

Leotiomycetes Helotiales Bulgariaceae BulgariainquinansisloteAFTOL-ID916 91841147

Dermateaceae PeziculacarpineaisolateAFTOL-ID938 91841226

Dothideomycetes Capnodiales Davidiellaceae MycosphaerellatassianastrainTS01 238734423

Capnodiaceae Leptoxyphiumsp.MUCL43740 50726934

Pleosporales Pleosporaceae Alternariasp.enrichmentculturecloneNJ-F7 270311614

Glyphiumelatum 17104830

Phomasp.CCF3818 213876689

Incertaesedis Norrliniapeltigericola 56555555

Sordariomycetes Xylariales MitosporicXylariales Dicymaolivacea 13661088

Hypocreales Mitosporic

Hypocreales

Fusariumoxysporum 291482357

Ophiocordycipitaceae Hirsutellacitriformis 11125693

Incertaesedis PutativePaecilomycessp.080834 89112992

Diaporthales Valsaceae ValsellasalicisisolateAFTOL-ID2132 112785209

Cryphonectriaceae ChrysoporthecubensisisolateAFTOL-ID2122 112785199

Basidiomycota Ustilaginomycetes Ustilaginales Ustilaginaceae Pseudozymasp.JCC20718S 77167276

Agaromycetes Polyporales Polyporaceae Coriolopsisbyrsina 288557592

Agaricales Cyphellaceae Radulomyceshiemalisisolate5444a 116687716

Auriculariales Auriculariaceae AuriculariaceaecloneAmb18S699 134022019

Russulales Peniophoraceae Peniophoranuda 2576440

Tremellomycetes Tremellales Tremellaceae Cryptococcusvishniacii 7262452

Filobasidiales Filobasidiaceae Filobasidiumglobisporum 21326776

Cystofilobasidiales Cystofilobasidiaceae Cystofilobasidiuminfirmominiatumisolate AFTOL-ID1888

109289344

Microbotrymycetes Leucosporidiales Nonidentified LeucosporidiumscottiisolateAFTOL-ID718 51859977 Sporidiobolales Mitosporic

Sporidiobolales

RhodotorulaglutinisAFTOL-ID720 111283841

Blastocladiomycota Blastocladiomycetes Blastocladiales Catenariaceae Catenomycessp.JEL342isolateAFTOL-ID47 49066429 Chytridiomycota Chytridiomycetes Chytridiales Chytridiaceae BlyttiomyceshelicusisolateAFTOL-ID2006 108744678

Chytriomycessp.JEL378isolateAFTOL-ID 1532

108744670

Chytriomycetaceae EntophlyctishelioformisisolateAFTOL-ID40 49066425

Entophlyctissp.JEL174isolateAFTOL-ID38 49066423 Cladochytriaceae PolychitriumaggregatumstrainJEL109 47132215 Rhizophlyctidiales Rhizophlyctidaceae RhizoplhyctisroseaisolateAFTOL-ID43 490664428

RhizophydiumelyenseisolateAFTOL-ID693 108744666

TriparticalcararcticumisolateAFTOL-ID696 108744667 Fungiincertae

sedis

Mucoromycotina Mucorales Mucoraceae MucorplumbeusstrainUPSC1492 33334392

Thamnidiaceae Backusellactenidia 11078007

Fungi/metazoan incertaesedis

Protozoa Eccrinales Eccrinaceae EccrinidusflexilisisolateSPA11C45 50083273

Rozellida Rozelliidae RozellaallomycisisolateAFTOL-ID297 49066437

Rozellasp.JEL347isolateAFTOL-ID16 47132211

Ichthyosporeae Nonidentified Nonidentified Ichthyoponidasp.LKM51 3894141

Ichtyophonida Nonidentified Anurofecarichardsi 4322029

Nonidentified Choanoflagellida Acanthoecidae Stephanoecadiplocostata 37359232

Salpingoecidae Lagenoecasp.antarctica 120407515

Alveolata Dinophyceae Nonidentified Unclassified

Dynophyceae

22 B.Valderramaetal./RevistaMexicanadeBiodiversidad87(2016)18–28

fungiso wedecided toleave allambiguoussequencesinthe set for further analysis. Approved sets were automatically aligned using the Clustal W algorithm (Larkin et al., 2007) containedinMegaversion4(Tamura,Dudley,Nei,&Kumar, 2007).Mostofthesequencealignedinthefirstround,although optimizationof the surroundingsof variable regionsrequired manualalignment.Vectorbornefragmentswereremovedafter alignment.Asetofribosomalsequencesfromwell-identified organisms(Table1)wasaddedtoeach alignmentforinternal referenceandthegroupwasre-alignedandmanuallyoptimized withClustalW.Wesometimesdetectedgroupsofexperimental sequences that did not cluster with reference sequences but withinthemselves.Inthesecasesweidentifiedeachoneofthe sequences by looking for the closestmatch in the databases usingtheBLASTtool.Forsomesequences,theclosestmatch resulted to be an entry from a characterized species but in othercaseswe recoveredentriesfromenvironmentalsurveys. Phylogenies were reinforced by including sequences from characterizedspeciestothereferencesequencelistand, some-times,sequencesfromunculturedsources(Table2).Sequence clusteringwasperformedusingtheNeighborJoiningalgorithm (Saitou&Nei,1987)containedinMegaversion4.

Results

Amplificationoffungal18SribosomalDNAfromreference isolates

Control genomic DNA from different sources was tested foramplificationwithprimersnu-SSU-0817andnu-SSU-1536. Templates from non-fungal sources were unable to support amplification while fungal sources specifically amplified the internalfragmentof18SrDNA(datanotshown).In5outof6 fungalsamples(A.nidulans,D.hansenii,Y.lipolytica,S. cere-visiae,andB.adusta)thesizeoftheamplifiedproductmatched theexpected762bp(datanotshown).Sequencedataqualitywas assessedbysequencingacontrollibrarygeneratedby amplifi-cationof18SrDNAfromS.cerevisiae.

Identificationandphylogeneticanalysisofnu-SSU-0817 andnu-SSU-1536amplificationlibraries

TotalDNAfromwatersamplesfrom11differentsites(see Section ‘Materialsandmethods’)wasisolated, afragment of the 18S rDNA amplified and cloned in genetic libraries for individual clonesequencing.In thoserarecaseswhererDNA

Table2

Non-culturedreferencesequencesusedinthiswork.

Definition CloneID GInumber ClosestmatchbyBLAST

Unculturedfungi CloneBAQA254 20377933 Phaeopleosporaeugeniicola(Ascomycota)

UnculturedbasidiomycetecloneH18E128 149786618 Filobasidiumglobisporum(Basidiomycota) UnculturedbasidiomycetecloneMV2E89 149786738 Cryptococcusvishniacci(Basidiomycota) UnculturedbasidiomycetecloneMV5EEF18 149786752 Pseudozymasp.(Basidiomycota) UnculturedbasidiomycetecloneLC235EP14 95115857 Pseudozymasp.(Basidiomycota)

Unculturedascomycete 27530772 Davidiellatassiana(Ascomycota)

UnculturedascomycetecloneLC234EP18 95115853 Bulgariainquinans(Ascomycota)

Unculturedascomyceteisolate 21902393 Phomasp.(Ascomycota)

Unculturedrhizosphereclone 23504803 Mucorplumbeus(Mucoromycotina)

UnculturedChytridiomycotacloneMV5E291 149786790 Rhizophydiumelyensis(Chytridiomycota)

CloneCCW24 29423782 Triparticalcararcticum(Chytridiomycota)

CloneCCW48 27802600 Entophlyctisconfervae-glomeratae(Chytridiomycota)

Clonecontrol46 151413777 Rozellasp.JEL347(Chytridiomycota)

CloneRBfung138 90904231 Candidasp.Y6EG-2010(Ascomycota)

CloneWIM48 113926798 Basidiobolushaptosporus(Fungiincertaesedis)

CloneF47(S2) 86604435 Preussialignicola(Ascomycota)

CloneNAMAKO-37 114217391 Basidiobolushaptosporus(Fungiincertaesedis)

CloneSSRPD64 126033366 Phaeophleosporaeugeniicola(Ascomycota)

CloneZeuk2 59709949 Phaeophleosporaeugeniicola(Ascomycota)

Unculturedeukaryotes Clone051025T2S4WTSDP12094 223030789 Cryothecomonaslongipes(Cryomonadida)

Clone18BR20 124541005 Paracalanusaculeatus(Copepoda)

CloneSCM15C21 56182170 Pentapharsodinumtyrrhenicum(Dinoflagellate)

CloneSCM27C27 50541716 Acartialongiremis(Copepoda)

CloneSCM28C135 56182295 Diaphanoecagrandis(Choanoflagellidae)

CloneSCM37C13 50541727 Pantachogonhaeckeli(Cnidaria)

CloneSCM38C38 50541719 Paracalanusparvus(Copepoda)

CloneSCM38C41 56182194 Ichthyodiniumchabelardi(Alveolata)

CloneSCM38C62 56182178 Dinophyceaesp.CCMP1878(Dinoflagellate)

CloneSCM38C9 50541718 Paracalanusparvus(Copepoda)

CloneSSRPB26 126033229 Gymnodiniumaureolum(Alveolata)

CloneTAGIRI-8 67624905 Gymnodiniumbeii(Alveolata)

CloneCYSGM-24 133778655 Amastigomonasmutabilis(Apusozoa)

IsolateE3 30144455 Duboscquellasp.Hamana/2003(Alveolata)

CloneMB04.31 146157556 Oithonasimilis(Copepoda)

sequences from phylogenetic groups other than fungi were recovered,thesewereremovedfromthecollectionbefore clus-tering. The only exception to this behavior was the sample from Carpintero lagoon, where the 146 sequences recovered weremoresimilartoreferencesequencesfromdinoflagellates thanfromfungi.Thissetofsequenceswasremovedfromour analysis.

Clusteringanalysisofthelibraries

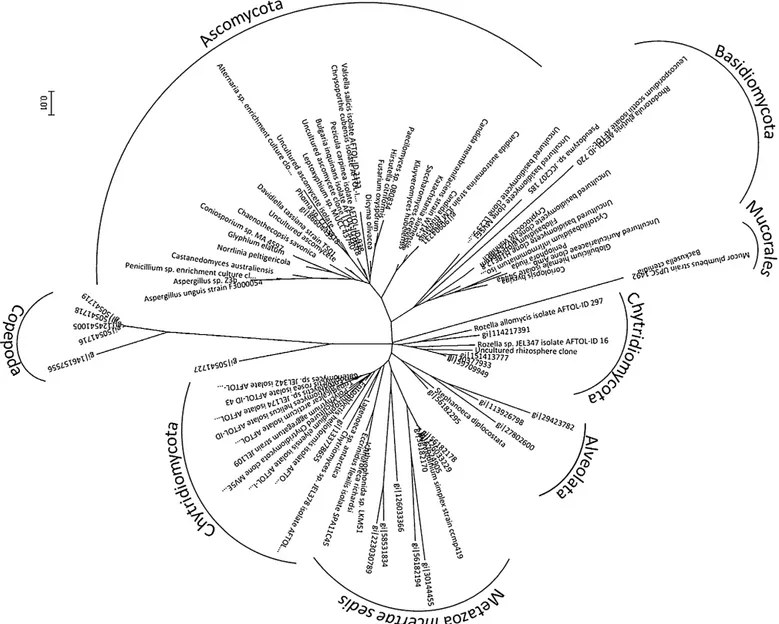

Wetestedtheabilityofourmolecularmarker,afragmentof the 18rDNA gene containing regionsV4–V8, toreconstruct a clustering profile consistent withthe taxonomic classifica-tionusingourensembleofreferencesequences(Fig.1).Once therobustnessoftheclusteringmethodwasdemonstrated,the environmental sequences from 10 of our 11 libraries (after removingthesamplesfromCarpinteroLagoonforthereasons described above) were organizedby site along withthe fun-galreferencesequencesasdescribedinSection‘Materialsand

methods’. Serialreconstructions of the 10libraries were per-formedusingthemanuallyoptimizedmultiplealignmentfrom each site, whichincluded the recovered referencesequences, untilarobustandinformativephylogramwasobtained.Based onthesephylograms,weidentifiedthemostprobabletaxonomic classificationoftheenvironmentalsequencesbytheirclustering withreferencesequences.

Bythemethodologydescribedabove,wewereableto iden-tify529oftheenvironmentalsequencesatthefamilylevel,1077 attheorderleveland288attheClass/Subphylumlevel.Only 326sequences,allfromthesamesite,didnotgroupwithany ref-erencesequencebuttouncultivatedclonesfrommarinesources (Table3).ThemostabundantphylumfoundwasAscomycota (1458sequences)(Fig.2),followedbyChytridiomycota(133 sequences)(Fig.3).Sequencesbelongingtophylum Basidiomy-cota(45sequences)(Fig.4)andtosubphylumMucoromycotina (21 sequences)wereseldom recovered as wellas non-fungal sequencesbelongingtoChoanoflagellidaeandEccrinales (29 sequences)(Fig.5).

24

B.

V

alderr

ama

et

al.

/

Re

vista

Me

xicana

de

Biodiver

sidad

87

(2016)

18–28

Table3

Identificationofenvironmentalsequences.

Sampledsites

Phylum Class/Subphylum Order Family Genus Zempoala Carboneras Mezquital Cruz Huanacaxtle

Vicente Guerrero

Media Luna

El rabón

Zacapulco Santa Catarina

Bahía Banderas

Totalby genus

Saccharomycetes (363)

Saccharomycetales Mitosporic Saccharomycetal

Candida 63 6 69

Nonidentified Nonidentified 9 213 71 293

Nonidentified Nonidentified Nonidentified 1 1

Nonidentified(260) Nonidentified Nonidentified Nonidentified 7 253 260

Leotiomycetes(3) Heliotiales Dermateaceae Pezicula 3 3

Ascomycota (1279)

Eurotiomycetes (18)

Eurotiales Trichocomaceae Aspergillus 1 1 5 7

Chaetothyriales Nonidentified Nonidentified 6 6

Verrucarriales Verrucariaceae Norrlinia 1 1

Nonidentified Nonidentified Nonidentified 4 4

Sordariomycetes (630)

Hypocreales Nonidentified Nonidentified 1 10 109 120

Diaporthales Cryphonectriaceae Chysoporthe 8 1 9

Hypocreales Mitosporic Clavicipitaceae

Paecilomyces 24 12 61 11 234 26 368

Nonidentified Nonidentified 133 133

Euascomycetes(1) Pleosporales Pleosporaceae Phoma 1 1

Dotyideomycetes(1) Capnodiales Davidiellaceae Davidiella 1 1

Nonidentified(3) Nonidentified Nonidentified Nonidentified 2 1 3

Mucorales(27) Nonidentified(27) Nonidentified Nonidentified Nonidentified 4 4 19 27

Chytridiomycota (299)

Nonidentified Nonidentified Nonidentified 3 3

Nonidentified Nonidentified 35 35

Spizellomycetales Spizellomyceteaceae Tripalcalcar 6 6

Spizellomycetales incertaesedis

Rozella 13 179 4 23 1 5 225

Chytridiomycetes (299)

Chytridiales Endochytriaceae Nonidentified 1 1

Nonidentified Nonidentified 4 4

Chytridiaceae Blyttiomyces 10 10

Chytriomyces 1 3 4

Cladochytriaceae Polychytrium 4 4

Rhizophydiales Rhizophydiaceae Rhizophydium 4 2 1 7

Basidiomycota (40)

Tremellomycetes (9)

Filobasidiales Nonidentified Nonidentified 3 3

Filobasidieaceae Nonidentified 2 1 3

Cystofilobasidales Cystofilobasidiaceae Nonidentified 3 3

Agaromycetes(14) Polyporales Nonidentified Nonidentified 1 13 14

Pucciniomycotina(2) Microbotrimycetes Leucosporidiales Leucosporidium 2 2

Atractielomycetes(2) Soporidiobolales Nonidentified Nonidentified 2 2

Ustilagomycetes(2) Nonidentified Nonidentified Nonidentified 2 6 8

Nonidentified(5) Nonidentified Nonidentified Nonidentified 1 4 5

Marineclones (326)

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

Dotyideomycetes/Capnodiales/Capnodiaceae (1) Dotyideomycetes/Capnodiales/Davidiellaceae (1) Leotiomycetes/Helotiales/Dermateaceae, Bulgariaceae (2) Leotiomycetes/Helotiales/Non identified (2)

Sordariomycetes/Diaporthales/Non identified (4) Sordariomycetes/Hypocreales/Ophiocordycipitaceae (4) Eurotiomycetes/Mycocaliciales/Trichocomaceae (5) Sordariomycetes/Hypocreales/Incertae sedis (6) Zemp

oala

Carboner as

Mezquital

Cruz huan aca

xtle

Vice nte gu

errero Med

ia luna El r

abón

Tapachula Santa catar

ina

Bah ía de bander

as

Figure2.AscomycotadiversityinthesampledsitesidentifiedbyClass(sub-phyllum)/order/family.

Diversityestimation

MolecularOperationalTaxonomicalUnits(MOTUS) diver-sity was estimated using the Shannon Index, which gives a measure of both species numbers and the evenness of their abundanceaspresentedinTable4(Shannon,1948).Thevalue of the index ranges from low values (reduced species rich-nessandevenness)tohighvalues(extendedspeciesevenness and richness). In this work, the lowest diversity value was obtainedforMediaLunaandBahíadeBanderas,sampleswith a single MOTU identified in each (H=0). In contrast, the

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Chytridiomycetes/Rhizophydiales/Rhizophydiaceae (4) Chytridiomycetes/Chytridiales/Chytridiaceae (4)

Chytridiomycetes/Spizellomycetales/Spizellomycetaceae (14) Non identified (33)

Chytridiomycetes/Chytridiales/Non identified (10) Chytridiomycetes/Spizellomycetales/Non identified (35) Zempo

ala

Carboner as

Mezquital

Cruz huanacaxtleVicen

te guerrero Medi a luna

El r abón

Tapa chula

Santa catar ina

Bahía de bander as

Figure3.ChytridiomycotadiversityinthesampledsitesidentifiedbyClass(sub-phyllum)/order/family.

highestdiversityvaluewasobtainedfortheZempoalalagoon (H=2.285), slightlyhigherthanthe totaldiversitybyfamily (H=2.130).

26 B.Valderramaetal./RevistaMexicanadeBiodiversidad87(2016)18–28

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Non identified (15) Ustilaginomycetes/Non identified (8)

Mycrobotryomycetes/Leucosporidiales/Non identified (2) Tremellomycetes/Cystofilobasidales/Cystofilobasidiaceae (3) Mycrobotryomycetes/mitosporic Sporidiobolales (2)

Agaricomycetes/Polyporales/Non identified (13) Tremellomycetes/Filobasidiales/Filobasidieaceae (2) Zempoala Carbon

eras Mezqui

tal

Cruz huan acaxt

le

Vicente guerre ro

Media luna El r abón

Tapachula San

ta catar ina

Bahía de bander as

Figure4.BasidiomycotadiversityinthesampledsitesidentifiedbyClass(sub-phyllum)/order/family.

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

Rozzellida/Rozelliidae/Non identified (33) Eccrinales/Ichtyosporeae (1)

Matches to uncultivated clones from marine sources (326)

Choanoflagellidae/Acanthoecidae (12) Mucoromycotina/Mucorales (21)

Choanoflagellidae/Salpingoecidae (17) Zempoa

la

Carboner as

Mezquital

Cruz h uanacaxtle

Vicente gue rrero

Media luna

El r abón

Tapachu la

Santa catar ina

Bahía de band eras

Figure5.NonfungalmicrobialdiversityinthesampledsitesidentifiedbyClass(sub-phyllum)/order/family.

Discussion

Inaquaticenvironmentsorganicmatterdecompositionoccurs throughacomplexbutwelldefinedfungalsuccession(Barlocher &Kendrick,1974;Gessner, Thomas,Jean-Louis, &Chauvet, 1993).Themostcommonapproachusedforaquaticfungi diver-sity surveys involvesthe collection of organic material from natural sources such as plant debris or from artificial baits andthemicroscope-basedestimationofspeciesrichness.Using thisapproach, richness depends on the ability of the species inthecommunitytosporulate.Alternatively,molecular meth-ods may be applied for the identification of fungal species,

independentlyoftheirmetabolicstatusorlifecyclestage. Com-parative studies performed on decaying leaves indicate that bothapproachesarecomplementaryintheelucidationof pop-ulationcompositionanddynamics(Nikolcheva,Cockshutt,& Barlocher,2003).

Table4

Shannondiversityvaluescalculatedforthesampledsite.

Location Environment Npersite Spersite Hpersite

Zempoala Freshwatertemperatelagoon 171 25 2.285

Carboneras Brackishcoastallagoon 215 9 0.743

Mezquital Marinecoastallagoon 85 4 0.769

CruzdeHuanacaxtle PacificOceancoastline 64 8 1.749

VicenteGuerrero Dam 153 7 0.583

MediaLuna Brackishcoastallagoon 213 1 0

Elrabón Hypersalinecoastallagoon 241 3 0.148

Zacapulcp Mangroveswamp 361 8 0.906

SantaCatarina Artificialwaterreservoir 164 6 1.003

BahíadeBanderas PacificOceancoastline 326 1 0

Totalbyfamily 1,993 39 2.130

ofthesestudiesreferonlytocertaingroupsoffungi(yeasts,for example).

SmallsubunitribosomalDNAsequences(18SrDNA)have beenusedasmolecularmarkersforreconstructingfungal taxon-omy(Brunsetal.,1992;Hibbettetal.,2007;Jamesetal.,2006) andforthedescriptionoffungaldiversityinsoilsandwater bod-ies(Andersonetal.,2003;Huntetal.,2004;Monchyetal.,2011; Piquetetal.,2011).SmallsubunitrDNAsequenceshavebeen usedtoexplorebiologicaldiversityandspecializedsoftwarehas beendevelopedtodiscriminateamongprokaryoticand eukary-oticsequences(Bengtssonetal.,2011).18SrDNAsequencesare stillwidelyusedtoexploreenvironmentalsamples.Thesetof primersusedherewasdesignedfortheamplificationoffungal ribosomalDNA,inparticularaninternalfragmentof the18S ribosomalparticlegene betweenvariable regionsV4 andV8 (Borneman&Hartin,2000).Intheoriginalpapertheseprimers wereunabletoamplifyDNAisolatedfromorganismsotherthan fungiandoperationalspecificitywasdemonstratedbythe tar-getedamplificationoffungal18Sribosomalsequencesfromsoil samples(Andersonetal.,2003).

Species designation of non-cultured individuals based on molecularmarkers presentsthe intrinsicweakness of lacking a statistically sound method. In some cases the identifica-tion is based on the overall similarity of query sequences to referencesequencesinpublic databases in paired alignments usingarbitrarilydesignatedlimits.Inordertoenforcethe tax-onomical robustness of our work, we adapted the identity interval rank concept originally devised for the classifica-tionof plant-nodulatingbacterial species (Lloretet al.,2007; Martínez-Romero, Orme˜no-Orrillo, Rogel, López-López, & Martínez-Romero,2010).

Our approach is based on clustering of experimental sequences and a set of taxonomically classified reference sequencesencompassingknownfungalphylaandbasallineages. This gives enough information to reconstruct the taxonomic classificationofthe organisms.Sometimes clusteringpatterns were sensitive to the distribution of experimental sequences unlessmorereferencesequenceswereincluded.Inthesecases, we identified clusters of experimental entries lacking refer-ence sequences and used them to retrieve their best match inthe databases. Inclusionof thesenewreference sequences in the alignments settled tree topology. Each cluster was

taxonomicallyidentifiedusingtheclassificationofthereference sequenceslocated within, atdifferent levels,from phylumto family.

The sequencevariabilityof the 18S rDNAfragments sup-portstheclusteringreconstruction of ourreferencesequences assembledwithtaxonomicconsistency.Thisincludesthe iden-tificationof asubgroupof Chytridiomycetesbelongingtothe

Rozella genus,whichisknown tocluster separately(Hibbett etal.,2007).Itisimportanttonotethatwewereabletorecover sequencesfrom allfungal phyla, indicatinglittle bias for the collection procedureor the amplificationprimers used.From theentire collection,23.8%ofthe sequencescould be identi-fiedatthefamilylevel,48.5%attheorderleveland13%atthe class/subphylumlevel.

Theimportant roleof woodandleaflitterdegradation has beenascribedtoaquaticascomycetessincebasidiomycetesare scarce inwaterhabitats andotherorganismssuch asbacteria rarelyhavetheabilitytocompletelymineralizelignin(Simonis, Raja, &Shearer, 2008). Thus, it was not surprising that the Ascomycota was the most frequently recovered phylum and Sordariomycetesthemostfrequentlyrecoveredclass.The occur-renceofnon-identifiedascomyceteswasdocumentedinonly3 ofthesampledsitessupportingthatideathatthisphylumisthe best characterized eveninaquatic habitats. The second most abundantphylumdescribedinaquaticenvironmentsis Chytrid-iomycotaand,accordingly, itwasthe secondmostfrequently foundgroupforoursequencewith41%ofthesequences iden-tifiedatthefamilylevel.

28 B.Valderramaetal./RevistaMexicanadeBiodiversidad87(2016)18–28

Acknowledgments

ThisworkwaspartiallyfundedbygrantConacyt-Semarnat 2004-01-0100.WearegratefultoJoséLuisFernándezandDr. VíctorGonzálezfromCCG-UNAMforDNAsequencingand Prof.MichaelA.Pickardforcriticalreadingofthemanuscript.

References

Altschul,S.F.,Madden,T.L.,Schaffer,A.A.,Zhang,J.,Zhang,Z.,Miller,W., etal.(1997).GappedBLASTandPSI-BLAST:anewgenerationofprotein databasesearchprograms.NucleicAcidsResearch,25,3389–3402.

Anderson,I.C.,Campbell,C.D.,&Prosser,J.I.(2003).Potentialbiasoffungal 18SrDNAandinternaltranscribedspacerpolymerasechainreactionprimers forestimatingfungalbiodiversityinsoil.EnvironmentalMicrobiology,5, 36–47.

Barlocher,F.,&Kendrick,B.(1974).Dynamicsofthefungalpopulationon leavesinastream.JournalofEcology,62,761–791.

Bengtsson, J.,Eriksson, K. M.,Hartmann, M.,Wang, Z., Shenoy, B. D., Grelet,G.A.,etal.(2011).Metaxa:asoftwaretoolforautomated detec-tion and discrimination amongribosomal small subunit (12S/16S/18S) sequences of archaea, bacteria, eukaryotes, mitochondria, and chloro-plastsinmetagenomesandenvironmentalsequencingdatasets.AntonieVan Leeuwenhoek,100,471–475.

Borneman,J.,&Hartin,R.J.(2000).PCRprimersthatamplifyfungalrRNA genesfromenvironmentalsamples.AppliedandEnvironmental Microbiol-ogy,66,4356–4360.

Bruns,T.D.,Vilgalys,R.,Barns,S.M.,González,D.,Hibbett,D.S.,Lane,D. J.,etal.(1992).Evolutionaryrelationshipswithinfungi:analysesofnuclear smalsubunitrRNAsequences.MolecularPhylogeneticsandEvolution,1, 231–241.

Chapin,F.S.,Zavaleta,E.S.,Eviner,V.T.,Naylor,R.L.,Vitousek,P.M., Reynolds,H. L.,etal. (2000).Consequences ofchanging biodiversity. Nature,405,234–242.

Gessner,M.O.,Thomas,C.M.,Jean-Louis,A.M.,&Chauvet,E.(1993).

Stablesuccessionalpatternsofaquatichyphomycetesonleavesdecayingin asummercoolstream.MycologicalResearch,97,163–172.

González,M.,Hanlin,R.,Herrera,T.,&Ulloa,M.(2000).Fungicolonizing hair-baitsfromthreecoastalbeachesofMexico.Mycoscience,41,259–262.

González,M.,Hanlin,R.,&Ulloa,M.(2001).Achecklistofhighermarine fungiofMexico.Mycotaxon,80,241–253.

González,M.C.,&Chavarría,A.(2005).Somefreshwaterascomycetesfrom Mexico.Mycotaxon,91,315–322.

Guzmán,G.(1998).InventoryingthefungiofMexico.Biodiversityand Con-servation,7,369–384.

Hawksworth,D.L.(1991).Thefungaldimensionofbiodiversity:magnitude, significance,andconservation.MycologicalResearch,95,641–655.

Hawksworth,D.L.(2001).Themagnitudeoffungaldiversity:the1.5million speciesestimaterevisited.MycologicalResearch,105,1422–1432.

Heredia,G.,Reyes,M.,Arias,R.M.,Mena-Portales,J.,&Mercado-Sierra,A. (2004).Adicionesalconocimientodeladiversidaddeloshongos conidi-alesdelbosquemesófilodemonta˜nadelestadodeVeracruz.ActaBotanica Mexicana,66,1–22.

Hibbett,D.S.,Binder,M.,Bischoff,J.F.,Blackwell,M.,Cannon,P.F.,Eriksson, O.E.,etal.(2007).Ahigher-levelphylogeneticclassificationoftheFungi. MycologicalResearch,111,509–547.

Hunt,J.,Boddy,L.,Randerson,P.F.,&Rogers,H.J.(2004).Anevaluationof 18SrDNAapproachesforthestudyoffungaldiversityingrasslandsoils. MicrobialEcology,47,385–395.

James,T.Y.,Kauff,F.,Schoch,C.L.,Matheny,P.B.,Hofstetter,V.,Cox,C.J., etal.(2006).Reconstructingtheearlyevolutionoffungiusingasix-gene phylogeny.Nature,443,818–822.

Kimura,N.(2006).Metagenomics:accesstounculturablemicrobesinthe envi-ronment.MicrobesandEnvironments,21,201–215.

Klaubauf,S.,Inselsbacher,E.,Zechmeister-Boltenstern,S.,Wanek,W., Gotts-berger, R., Strauss, J., et al. (2010). Molecular diversity of fungal communitiesinagriculturalsoilsfromLowerAustria.FungalDiversity, 44,65–75.

Larkin,M.A.,Blackshields,G.,Brown,N.P.,Chenna,R.,McGettigan,P. A.,McWilliam,H.,etal.(2007).ClustalWandClustalXversion2.0. Bioinformatics(Oxford,England),23,2947–2948.

LeCalvez,T.,Burgaud,G.,Mahé,S.,Barbier,G.,&Vandenkoornhuyse,P. (2009).Fungaldiversityindeep-seahydrothermalecosystems.Appliedand EnvironmentalMicrobiology,75,6415–6421.

Lloret,L.,Orme˜no-Orrillo,E.,Rincón-Rosales,R.,Martínez-Romero,J., Rogel-Hernández,M.A.,&Martínez-Romero,E.(2007).Ensifermexicanumsp. nov.anewspeciesnodulatingAcaciaangustissima(Mill.)KuitzeinMexico. SystematicandAppliedMicrobiology,30,280–290.

Martínez-Romero,J.C.,Orme˜no-Orrillo,E.,Rogel,M.A.,López-López,A., & Martínez-Romero,E.(2010).Trendsinrhizobialevolutionandsome taxonomicremarks.InP.Pontarotti(Ed.),Evolutionarybiology–concepts, molecularandmorphologicalevolution(pp.301–315).Berlin:Springer.

Monchy,S.,Sanciu,G.,Jobard,M.,Rasconi,S.,Gerphagnon,M.,Chabe,M., etal.(2011).Exploringandquantifyingfungaldiversityinfreshwaterlake ecosystemsusingrDNAcloning/sequencingandSSUtagpyrosequencing. EnvironmentalMicrobiology,13,1433–1453.

Moon-vanderStaay,S.Y.,DeWachter,R.,&Vaulot,D.(2001).Oceanic18S rDNAsequencesfrompicoplanktonrevealunsuspectedeukaryoticdiversity. Nature,409,607–610.

Mueller,G.,&Schmit,J.(2007).Fungalbiodiversity:whatdoweknow?What canwepredict?BiodiversityandConservation,16,1–5.

Mueller,G.M.,Bills,G.F.,&Foster,M.S.(2004).Biodiversityoffungi inven-toryandmonitoringmethods(Vol.1)Burlington,MA:ElsevierAcademic Press.

Nikolcheva, L.G.,Cockshutt, A.M.,& Barlocher,F.(2003).Determining diversityoffreshwaterfungiondecayingleaves:comparisonoftraditional andmolecularapproaches.AppliedandEnvironmentalMicrobiology,69, 2548–2554.

Piquet,A.M.,Bolhuis,H.,Meredith,M.P.,&Buma,A.G.(2011).Shiftsin coastalAntarcticmarinemicrobialcommunitiesduringandaftermelt water-relatedsurfacestratification.FEMSMicrobiologyEcology,76,413–427.

Saitou,N.,&Nei,M.(1987).Theneighbor-joiningmethod:anewmethod forreconstructingphylogenetictrees.MolecularBiologyandEvolution,4, 406–425.

Shannon,C.E.(1948).Amathematicaltheoryofcommunication.BellSystem TechnicalJournal,27,379–423.

Shearer,C.,Descals,E.,Kohlmeyer,B.,Kohlmeyer,J.,Marvanova,L.,Padgett, D.,etal.(2007).Fungalbiodiversityinaquatichabitats.Biodiversityand Conservation,16,49–67.

Simonis,J.L.,Raja,H.A.,&Shearer,C.A.(2008).Extracellularenzymesand softrotdecay:areascomycetesimportantdegradersinfreshwater?Fungal Diversity,31,135–146.

Tamura,K.,Dudley,J.,Nei,M.,&Kumar,S.(2007).MEGA4:Molecular Evolu-tionaryGeneticsAnalysis(MEGA)softwareversion4.0.MolecularBiology andEvolution,24,1596–1599.

Torsvik,V.,&Ovreas,L.(2002).Microbialdiversityandfunctioninsoil:from genestoecosystems.CurrentOpinioninMicrobiology,5,240–245.

Vainio,E.J.,&Hantula,J.(2000).Directanalysisofwood-inhabitingfungi usingdenaturinggradientgelelectrophoresisofamplifiedribosomalDNA. MycologicalResearch,104,927–936.

VanderAuwera,G.,DeBaere,R.,VandePeer,Y.,DeRijk,P.,VandenBroeck, I.,&DeWachter,R.(1995).ThephylogenyoftheHyphochytriomycota asdeducedfromribosomalRNAsequencesofHyphochytriumcatenoides. MolecularBiologyandEvolution,12,671–678.