Chromosomal Instability in Amniocytes

From Fetuses of Mothers Who Smoke

Rosa Ana de la Chica, MSc Isabel Ribas, PhD

Jesús Giraldo, PhD Josep Egozcue, MD Carme Fuster, PhD

T

HE LONG-TERM PUBLIC HEALTH consequences of regular to-bacco consumption include an increased risk of coagulation problems, cancer, cardiovascular dis-ease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and adverse effects on nancy. Maternal smoking during preg-nancy has many consequences both during and after pregnancy, such as in-fertility, coagulation problems, obstet-ric accidents such as extrauterine pregnancy or placenta previa, and in-trauterine growth retardation.1Arela-tionship between postnatal exposure to tobacco and childhood cancer, espe-cially leukemia and lymphomas, has also been suggested.2

Tobacco contains a high number of mutagenic compounds.3Recently, the

presence of tobacco-specific metabo-lites has been described in fetal blood and cell-free amniotic fluid (trans-ferred from the mother via placenta) and in newborns from women who smoke,4-6suggesting a possible

geno-toxic effect of smoking during preg-nancy. However, although many cyto-genetic studies have demonstrated the existence of an increased incidence of chromosomal aberrations, sister chro-matid exchanges (SCEs), micronu-clei, and fragile-site expression in pe-ripheral blood lymphocytes of adult

sible genotoxic effect of tobacco on the embryo and fetus are available. Only in-direct data using chorionic villi have been published11,12; in one case, an

in-crease in SCEs was found in direct preparations,11while in the other,

chro-mosomal lesions were not increased.12

In this study we assess the possible genotoxic effect of maternal smoking on amniotic fluid cells, based on the presence of an increased

chromo-ties. We also analyze whether any chro-mosomal regions are especially af-fected by exposure to tobacco in the fetus.

Author Affiliations:Departament de Biologia Cel·lular, Fisiologia i Immunologia, Facultat de Medicina, Uni-versitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain (Ms de la Chica and Drs Egozcue and Fuster); Centro de Patología Celular, Barcelona, Spain (Dr Ribas); and Uni-tat de Bioestadística, FaculUni-tat de Medicina, Universi-tat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra (Dr Giraldo). Context Tobacco increases the risk of systemic diseases, and it has adverse effects on pregnancy. However, only indirect data have been published on a possible geno-toxic effect on pregnancy in humans.

Objectives To determine whether maternal smoking has a genotoxic effect on am-niotic cells, expressed as an increased chromosomal instability, and to analyze whether any chromosomal regions are especially affected by exposure to tobacco.

Design, Setting, and Patients In this prospective study, amniocytes were ob-tained by routine amniocentesis for prenatal diagnosis from 25 controls and 25 women who smoke (ⱖ10 cigarettes/d forⱖ10 years), who were asked to fill out a smoking questionnaire concerning their smoking habits. Chromosomal instability was ana-lyzed in blinded fashion by 2 independent observers in routine chromosome spreads. Breakpoints implicated in chromosomal abnormalities were identified by G-banding. Main Outcome Measures Association between maternal smoking and increased chromosomal instability in amniotic fluid cells, expressed as chromosomal lesions (gaps and breaks) and structural chromosomal abnormalities.

Results Comparison of cytogenetic data between smokers and nonsmokers (con-trols) showed important differences for the proportion of structural chromosomal ab-normalities (smokers: 12.1% [96/793]; controls: 3.5% [26/752];P=.002) and to a lesser degree for the proportion of metaphases with chromosomal instability (smok-ers: 10.5% [262/2492]; controls: 8.0% [210/2637];P=.04), and for the proportion of chromosomal lesions (smokers: 15.7% [391/2492]; controls: 10.1% [267/2637]; P=.045). Statistical analysis of the 689 breakpoints detected showed that band 11q23, which is a band commonly implicated in hematopoietic malignancies, was the chro-mosomal region most affected by tobacco.

Conclusions Our findings show that smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day for at least 10 years and during pregnancy is associated with increased chromosomal insta-bility in amniocytes. Band 11q23, known to be involved in leukemogenesis, seems es-pecially sensitive to genotoxic compounds contained in tobacco.

METHODS

Patients

In this prospective study, amniocytes were obtained by amniocentesis for pre-natal diagnosis. The study group con-sisted of 25 women smokers and 25 nonsmoking women between the 13th and 26th postmenstrual week. Women were first personally interviewed at length by one author (I.R.) regarding their consumption of alcohol, coffee, and tea. Only if the answers were nega-tive were women asked to fill out the smoking questionnaire concerning their current and previous smoking habits, those of their husbands, and smoking in their occupational setting. Smokers had smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day for at least 10 years. Nonsmokers (controls) were not exposed to to-bacco at home or at work (ie, no

pas-sive smoking). In the smokers group, 5 fathers smoked 5 to 20 cigarettes per day (S2, S5, S7, S8, and S17), 10 fa-thers were nonsmokers (S1, S3, S12, S13, S15, S16, S18, S20, S23, and S25), and the smoking habits of the rest of the fathers was unknown. The first 25 women who fulfilled all of these con-ditions and were in good health were included in each group. In total, 800 in-terviews were carried out. Four hun-dred ninety-six interviews were re-quired to find the 25 nonsmokers who fulfilled the strict criteria set up in our protocol; 175 interviews were re-quired to find the 25 mothers who had smoked 10 or more cigarettes daily for at least 10 years and who continued smoking during pregnancy. The 129 re-maining interviews correspond either to women who smoked fewer than 10

cigarettes per day, those who had smoked for less than 10 years, or those who had quit smoking when they knew they were pregnant.

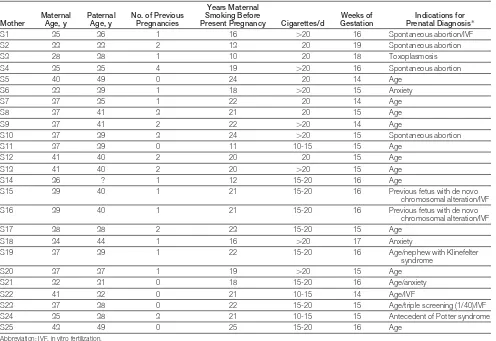

TABLE1andTABLE2present data for maternal age, paternal age, number of previous pregnancies, years of mater-nal smoking before present preg-nancy, number of cigarettes smoked per day, weeks of gestation, and the indi-cations for prenatal diagnosis for smok-ers and controls, respectively. The study was approved by the Universitat Au-tònoma de Barcelona institutional eth-ics committee. Informed consent was given in writing by all participants.

Cytogenetic Analysis

The amniotic fluid was centrifuged in 2 different tubes at 800 rpm for 5 min-utes at room temperature. The

super-Table 1.General Characteristics of the Mothers Who Smoke

Mother

Maternal Age, y

Paternal Age, y

No. of Previous Pregnancies

Years Maternal Smoking Before

Present Pregnancy Cigarettes/d

Weeks of Gestation

Indications for Prenatal Diagnosis*

S1 35 36 1 16 ⬎20 16 Spontaneous abortion/IVF

S2 33 33 2 13 20 19 Spontaneous abortion

S3 28 38 1 10 20 18 Toxoplasmosis

S4 35 35 4 19 ⬎20 16 Spontaneous abortion

S5 40 49 0 24 20 14 Age

S6 33 39 1 18 ⬎20 15 Anxiety

S7 37 35 1 22 20 14 Age

S8 37 41 3 21 20 15 Age

S9 37 41 2 22 ⬎20 14 Age

S10 37 39 3 24 ⬎20 15 Spontaneous abortion

S11 37 39 0 11 10-15 15 Age

S12 41 40 2 20 20 15 Age

S13 41 40 2 20 ⬎20 15 Age

S14 36 ? 1 12 15-20 16 Age

S15 39 40 1 21 15-20 16 Previous fetus with de novo

chromosomal alteration/IVF

S16 39 40 1 21 15-20 16 Previous fetus with de novo

chromosomal alteration/IVF

S17 38 38 2 23 15-20 15 Age

S18 34 44 1 16 ⬎20 17 Anxiety

S19 37 39 1 22 15-20 16 Age/nephew with Klinefelter

syndrome

S20 37 37 1 19 ⬎20 15 Age

S21 32 31 0 18 15-20 16 Age/anxiety

S22 41 32 0 21 10-15 14 Age/IVF

S23 37 38 0 22 15-20 15 Age/triple screening (1/40)/IVF

S24 35 38 3 21 10-15 15 Antecedent of Potter syndrome

[image:2.612.55.551.347.688.2]natant was removed under sterile con-ditions, leaving a pellet in 0.5 mL of amniotic fluid. Cells were resus-pended with fresh culture medium. Four cultures were set up: two 35-mm plastic petri dishes containing a 22-mm–square coverslip and 2 flat plas-tic tubes. The culture medium used for petri dishes was Chang (Irvine Scien-tific, Santa Ana, Calif ) with 1% peni-cillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, Calif ). The media used for tubes were RPMI:HAM-F10 (1:1) vitrogen) with 5.5% fetal calf serum (In-vitrogen); 2.5% ultroser G, which is a substitute for calf bovine serum (Ci-phergen Biosystems Inc, Fremont, Calif ); 2%L-glutamine (Invitrogen); and 1% penicillin-streptomycin

(Invit-and the medium changed every 2 to 3 days. Petri dishes were used only for prenatal diagnosis. For the present study, cultures from smokers and con-trols were both first grown in an RPMI: HAM-F10 medium. When cultures in a flat tube showed sufficient growth (ⱖ5 colonies), the cells were distrib-uted into 2 plastic petri dishes contain-ing Chang medium and harvested 24 hours later using an in situ fixation technique; colcemid was added for the last 45 minutes. The medium contain-ing colcemid was replaced by 0.8% so-dium citrate at room temperature for 12 to 15 minutes. A few drops of 3:1 methanol/acetic acid fixative were added to the hypotonic solution for 5 minutes. The fixative was replaced with

coverslips were allowed to dry under s p e c i f i c h u m i d i t y c o n d i t i o n s (48%-52%).

Preparations were stained with Leish-man stain (1:4 in LeishLeish-man buffer), coded, and evaluated for the presence of gaps and breaks by 2 authors (R.A.C., C.F.) blinded to participant smoking status. Differences were resolved by dis-cussion and consensus. Location and types of anomaly were recorded by each evaluator and compared at the end of the study. Cytogenetic evaluation was performed according to standard pro-cedures. Only high-quality meta-phases were analyzed. About 100 ran-domly selected metaphases uniformly stained were analyzed in each case. Later, preparations were destained for 1 minute in 3:1 methanol/acetic acid and immediately incubated for 10 to 30 minutes in 2xSSC at 65°C, washed with distilled water, air dried, and stained for 3 minutes with Wright Giemsa stain to identify the bands where the lesions were located. To characterize struc-tural chromosomal abnormalities (de-letions, acentric fragments, duplica-tions, translocaduplica-tions, inversions, and marker chromosomes), only high-quality banded metaphases were used; at least 25 banded metaphases per pa-tient were karyotyped.

Statistical Analysis

A generalized estimating equation (GEE)13was used for assessing the

[image:3.612.54.378.91.414.2]dif-ferences between the smoker and con-trol groups for the different types of chromosomal instability. The GEE ap-proach is an extension of generalized linear models designed to account for repeated within-individual measure-ments. This technique is particularly in-dicated when the normality assump-tion is not reasonable as, for instance, for discrete data. The GEE model was used instead of the classic Fisher ex-act test because the former takes into account the possible within-fetus cor-relation, whereas the latter assumes that all observations are independent. Since Table 2.General Characteristics of Nonsmoking Controls

Control Maternal Age, y Paternal Age, y No. of Previous Pregnancies Weeks of Gestation Indications for Prenatal Diagnosis*

C1 34 36 0 17 IVF (ICSI)

C2 36 36 2 16 Age/spontaneous abortion

C3 34 37 0 15 Anxiety

C4 34 35 3 16 Spontaneous abortion

C5 37 34 1 15 Age/spontaneous abortion

C6 34 32 1 16 Echographic fetal anomalies C7 34 42 0 16 Triple screening (1/77)⫹IVF (ICSI)

C8 37 37 4 14 Age

C9 33 36 2 13 Triple screening (1/151)

C10 29 29 0 16 IVF (ICSI)

C11 37 36 1 16 Age

C12 35 44 2 17 Age

C13 28 30 0 16 Triple screening (1/250) C14 34 30 1 15 Triple screening (1/64)

C15 33 35 1 14 Anxiety

C16 35 ? 0 15 IVF (ICSI)

C17 35 35 1 14 Triple screening (1/60)/spontaneous abortion

C18 26 28 0 26 Infection (cytomegalovirus) C19 30 33 2 16 Spontaneous abortion/IVF C20 39 41 3 17 Age/spontaneous abortion C21 37 38 2 16 Age/spontaneous abortion C22 31 31 2 16 Triple screening (1/188)/spontaneous

abortion

C23 36 38 1 15 Age/triple screening (1/85)

C24 31 31 0 23 Echographic signs/IVF

C25 36 36 0 ? Age/triple screening (1/41)

Abbreviations: ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF, in vitro fertilization.

for the inclusion in the model of addi-tional explanatory variables as covari-ates. In our analyses, the variance func-tion for the binomial distribufunc-tion and the logit link function were specified for the model. The response variable was defined as the number of chromo-somal anomalies/number of meta-phases tested for each fetus.

To identify which chromosome bands could be considered especially af-fected by the genotoxic effect of to-bacco, the fragile site multinomial method (version 995) was used.14,15This

multinomial statistical method is spe-cifically designed to identify chromo-somal fragile sites at loci where chro-mosome breaks are found. The fragile site multinomial method can be used for a maximum of 30 individuals, and the program performs the analyses for each individual separately and for the data pooled over all individuals. Be-cause the number of chromosomal ab-normalities per individual was much lower than the minimum (200 at the 400-band resolution level) required by the program to perform reliable esti-mates, only results from data pooled over the smoker and control groups were considered. The standardized2

andG2tests were used for assessing the

statistical significance of the chromo-some bands with breaks, gaps, or rear-rangements in each group.

To identify the bands with a greater sensitivity (implicated in structural chromosomal abnormalities or in chro-mosomal lesions) in smokers relative to controls, a variable was computed, defined for each band as the number of gaps and breaks (including those in-volved in structural abnormalities) in smokers minus their number in con-trols (difference). Bands with positive values in the computed variable indi-cated a greater tendency to break in smokers, while bands with negative val-ues suggested the opposite. In addi-tion, those bands with a computed dif-ference value more than 3 SDs from the mean difference were considered ex-treme values and selected for further

zero value for each of the individuals belonging to one group, alternative analyses such as the Fisher exact test and the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for which exactPvalue

com-putation was requested) were applied. Statistical significance was set at

P⬍.05. Statistical analyses were

car-ried out with SAS/STAT release 8.01 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). The GEE model was fitted using the REPEATED statement in the GENMOD proce-dure. The conservative type 3 score sta-tistics were used for the analysis of the model effects.16

RESULTS

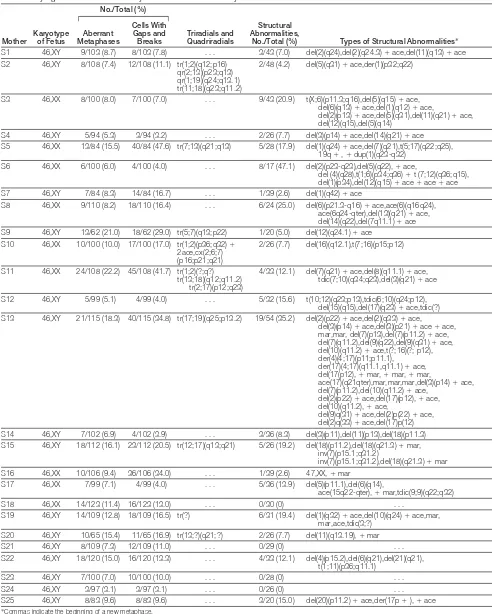

Chromosomal Instability in Amniocytes From Fetuses of Mothers Who Smoke

The number of metaphases with chro-mosomal instability, the frequency and type of chromosomal lesions, and the frequency of structural abnormalities in amniocytes from fetuses of the smoker and control groups are shown in TABLE3. The clinical data of the pa-tients (Tables 1 and 2) revealed that the mean maternal age in the smoker group was significantly higher than in the

con-not influence a study based on the analysis of lesions and structural ab-normalities, because maternal age in-fluences numerical but not structural abnormalities. In this regard, no sig-nificant correlation was obtained in our data between any of the above cytoge-netic variables and maternal age, within either the smoker or control groups. Nevertheless, because the GEE method used for the analysis allows for the in-clusion of continuous explanatory vari-ables as covariates, the contribution of age was considered. Moreover, the re-sults obtained for the whole sample were consistent with those from a par-ticular subset (all women except those who underwent in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection) in which no significant difference in ma-ternal age between smokers and con-trols was present. Finally, no differ-ences were found between smokers and controls for the number of weeks of gestation.

First, we used a reduced model in which age was not considered. In all analyses, the smoking effect was sig-nificant for chromosomal instability (smokers: 10.5% [262/2492]; con-Table 3.Frequency and Types of Chromosomal Instability in Amniocytes From Fetuses Carried by Smokers and Controls

Variable Smokers Controls

Total metaphases analyzed (uniform stain), No. 2492 2637 Total metaphases karyotyped (G-banded), No. 793 752 Chromosomal instability, No./total (%) 262/2492 (10.5) 210/2637 (8.0) Gaps and breaks, No. (%) (n = 2492) (n = 2637)

Total 391 (15.7) 267 (10.1)

Gaps 183 (7.3) 144 (5.5)

Breaks 208 (8.3) 123 (4.7)

Structural chromosomal abnormalities, No./total (%)* 96/793 (12.1) 26/752 (3.5)

Deletions 28 6

Deletions⫹acentric fragments 29 13

Acentric fragments 7 1

Translocations (⫹2der) 12 2

Dicentric translocations 5 2

Inversions 2 0

Duplications 1 0

Markers 11 2

Intrachromosomal reorganizations 1 0

*Similar values can be found in Price,17with 8% to 16% structural chromosomal abnormalities (total) and in Kerber and

[image:4.612.222.547.97.304.2]2492]; controls: 10.1% [267/2637];

P= .045), and to a higher degree for

structural chromosomal abnormali-ties (smokers: 12.1% [96/793]; con-trols: 3.5% [26/752];P= .002). In both

groups, the most frequent structural chromosomal abnormalities were de-letions and translocations (Table 3). De-letions (smokers: 7.2% [57/793]; con-trols: 2.5% [19/752]) and translocations (smokers: 2.1% [17/793]; controls: 0.5% [4/752]) were both also signifi-cant (P=.006 andP=.01, respectively).

Next, a model in which age was in-cluded as a covariate was considered. The age effect was not significant for any of the analyses performed (for chro-mosomal instability,P= .40;

chromo-somal lesions,P= .16; structural

chro-mosomal abnormalities, P= .64;

deletions,P= .40; and translocations, P=.10). The highPvalues obtained for

maternal age indicate that this factor does not influence the chromosomal anomalies observed and suggest that it could be removed from the model. Nev-ertheless, the model incorporating ma-ternal age was evaluated. The inclu-sion of this covariate increased theP

values of the smoking factor for all chro-mosomal anomalies analyzed. A nearly significant increase was observed in the percentage of metaphases with chro-mosomal instability in amniocytes from

fluential in amniocytes from smokers compared with those from controls (P= .10). In the smoker group, 2 cases

(S9 and S11) had metaphases with mul-tiple chromosomal lesions or pulver-ized cells; these metaphases were not included in the estimation of the num-ber of lesions. The much higher inci-dence of structural chromosomal ab-normalities in karyotyped metaphases in the smoker group than in the con-trol group remained significant (P=.01).

The incidence of deletions was higher in the smoker group than in the con-trol group (P= .01), while the

inci-dence of translocations became non-significant (P=.12). More than one third

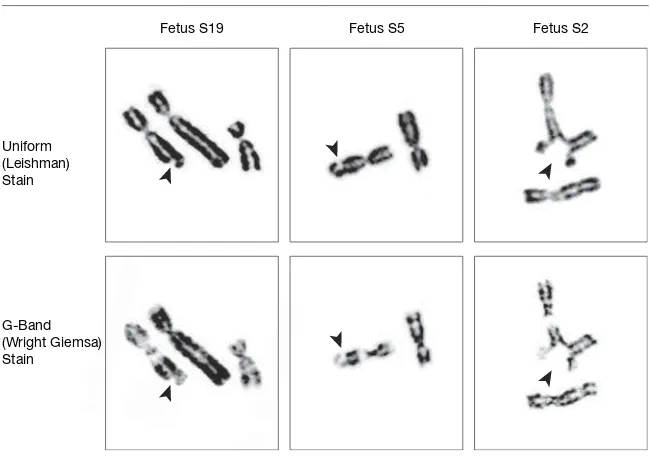

of the fetuses from mothers who smoke (36% [9/25]) had triradial or quadri-radial figures in their metaphases (S2, S5, S9, S10, S11, S13, S15, S19, and S20) (FIGURE1); in controls, only 1 quadri-radial was found (C24).

Finally, 5 smokers and 6 controls had become pregnant by in vitro fertiliza-tion or intracytoplasmic sperm injec-tion. To discard a possible effect of the hormonal treatment on the evaluation of the genotoxic effects of tobacco, the sta-tistical analyses were repeated exclud-ing these individuals. It is worth notexclud-ing that in this subset of women excluding those who had undergone in vitro fer-tilization or intracytoplasmic sperm

vious analyses, an extended model in-cluding maternal age as a covariate and a reduced model not including this fac-tor were considered. Similar results were obtained for both models. In the ex-tended model and as in the results ob-tained for the whole sample, maternal age showed no significant association with observed chromosomal anomalies. In this extended model, the results for the smoking factor reached statistical sig-nificance for both the proportion of meta-phases with chromosomal instability (smokers: 10.3% [200/1951]; controls: 7.2% [145/2023];P=.03) and the

pro-portion of structural chromosomal ab-normalities (smokers: 13.3% [83/624]; controls: 3.0% [17/570];P= .01) and

showed a marginal influence for the pro-portion of chromosomal lesions (smok-ers: 15.3% [298/1951]; controls: 9.0% [182/2023]; P= .08). The results

ob-tained for the reduced model reached sta-tistical significance for both the propor-tion of metaphases with chromosomal instability (P=.02) and the proportion of

structural chromosomal abnormalities (P=.002) and showed a nearly

signifi-cant association for the proportion of chromosomal lesions (smokers: 15.3% [298/1951]; controls: 9.0% [182/ 2023];P=.05).

Aneuploid metaphases were found in smokers and controls (smokers: 12.5% [99/793]; controls: 10.8% [81/752]) without showing statistical significance between them (P=.52 for the reduced

model;P=.36 for the extended model).

In sum, our results suggest that smoking during pregnancy has a geno-toxic effect that is not influenced by ma-ternal age.

Cytogenetic results for each indi-vidual are shown in TABLE 4 and TABLE5. All fetuses had normal consti-tutional karyotypes (46,XX or 46,XY). A p s e u d o m o s a i c i s m ( 4 6 , X Y , 8 3 % / 46,XY,t[X;1][p22.2;q25]17%) was de-tected in S16 but not confirmed after birth.

Specific Chromosome Bands Figure 1.Partial Metaphases of Amniocytes From Fetuses of Mothers Who Smoke, Showing

Spontaneous Chromosomal Instability

Quadriradials Multiple Breaks Multiple Gaps and Breaks

Fetus S2 Fetus S11 Fetus S13

Table 4.Cytogenetic Results in Amniocytes From Fetuses Carried by Mothers Who Smoke

Mother Karyotypeof Fetus

No./Total (%)

Triradials and Quadriradials

Structural Abnormalities,

No./Total (%) Types of Structural Abnormalities* Aberrant

Metaphases

Cells With Gaps and Breaks

S1 46,XY 9/103 (8.7) 8/103 (7.8) . . . 3/43 (7.0) del(2)(q24),del(2)(q24.3)⫹ace,del(11)(q13)⫹ace S2 46,XY 8/108 (7.4) 12/108 (11.1) tr(1;2)(q12;p16)

qr(2;13)(p23;q13) qr(1;19)(q24;q13.1) tr(11;18)(q23;q11.2)

2/48 (4.2) del(5)(q31)⫹ace,der(1)(p32;q22)

S3 46,XX 8/100 (8.0) 7/100 (7.0) . . . 9/43 (20.9) t(X;6)(p11.3;q16),del(5)(q15)⫹ace, del(6)(q13)⫹ace,del(1)(q12)⫹ace,

del(2)(p13)⫹ace,del(5)(q31),del(11)(q21)⫹ace, del(12)(q15),del(5)(q14)

S4 46,XY 5/94 (5.3) 3/94 (3.2) . . . 2/26 (7.7) del(3)(p14)⫹ace,del(14)(q21)⫹ace S5 46,XX 13/84 (15.5) 40/84 (47.6) tr(7;13)(q21;q13) 5/28 (17.9) del(1)(q24)⫹ace,del(7)(q21),t(5;17)(q22;q25),

19q⫹,⫹dup(1)(q23-q32) S6 46,XX 6/100 (6.0) 4/100 (4.0) . . . 8/17 (47.1) del(2)(p23-q23),del(5)(q22),⫹ace,

del (4)(q28),t(1;6)(p34;q36)⫹t (7;12)(q36;q15), del(1)(p34),del(12)(q15)⫹ace⫹ace⫹ace S7 46,XY 7/84 (8.3) 14/84 (16.7) . . . 1/39 (2.6) del(1)(q42)⫹ace

S8 46,XX 9/110 (8.2) 18/110 (16.4) . . . 6/24 (25.0) del(6)(p21.3-q16)⫹ace,ace(6)(q16q24), ace(6q24-qter),del(13)(q21)⫹ace, del(14)(q22),del(7q11.1)⫹ace S9 46,XY 13/62 (21.0) 18/62 (29.0) tr(5;7)(q13;p22) 1/20 (5.0) del(12)(q24.1)⫹ace

S10 46,XX 10/100 (10.0) 17/100 (17.0) tr(1;2)(p36;q32)⫹

2ace,cx(2;6;7) (p16;p21;q21)

2/26 (7.7) del(16)(q12.1),t(7;16)(p15;p12)

S11 46,XX 24/108 (22.2) 45/108 (41.7) tr(1;2)(?;q?) tr(13;18)(q12;q11.2)

tr(2;17)(p12;q23)

4/33 (12.1) del(7)(q21)⫹ace,del(8)(q11.1)⫹ace, tdic(7;10)(q34;q23),del(3)(q21)⫹ace S12 46,XY 5/99 (5.1) 4/99 (4.0) . . . 5/32 (15.6) t(10;12)(q23;p13),tdic(6;10)(q24;p12),

del(15)(q15),del(17)(q23)⫹ace,tdic(?) S13 46,XY 21/115 (18.3) 40/115 (34.8) tr(17;19)(q25;p13.2) 19/54 (35.2) del(2)(p22)⫹ace,del(2)(q33)⫹ace,

del(3)(p14)⫹ace,del(3)(p21)⫹ace⫹ace, mar,mar, del(7)(p13),del(7)(p11.2)⫹ace, del(7)(q11.2),del(9)(q22),del(9)(q31)⫹ace, del(10)(q11.2)⫹ace,t(?;16)(?; p12), der(4)(4;17)(p11;p11.1),

der(17)(4;17)(q11.1,q11.1)⫹ace, del(17(p12),⫹mar,⫹mar,⫹mar,

ace(17)(q21qter),mar,mar,mar,del(3)(p14)⫹ace, del(7)(p11.2),del(10)(q11.2)⫹ace,

del(2)(p22)⫹ace,del(17)(p12),⫹ace, del(10)(q11.2),⫹ace,

del(9)q(31)⫹ace,del(2)p(22)⫹ace, del(2)q(33)⫹ace,del(17)p(12) S14 46,XY 7/102 (6.9) 4/102 (3.9) . . . 3/36 (8.3) del(3)(p11),del(11)(p13),del(18)(p11.3) S15 46,XY 18/112 (16.1) 23/112 (20.5) tr(12;17)(q13;q21) 5/26 (19.2) del(18)(p11.2),del(18)(q21.3)⫹mar,

inv(7)(p15.1;q31.2)

inv(7)(p15.1;q31.2),del(18)(q21.3)⫹mar S16 46,XX 10/106 (9.4) 36/106 (34.0) . . . 1/39 (2.6) 47,XX,⫹mar

S17 46,XX 7/99 (7.1) 4/99 (4.0) . . . 5/36 (13.9) del(5)(p11.1),del(6)(q14),

ace(15q22-qter),⫹mar,tdic(9;9)(q22;q32) S18 46,XX 14/123 (11.4) 16/123 (13.0) . . . 0/30 (0) . . .

S19 46,XY 14/109 (12.8) 18/109 (16.5) tr(?) 6/31 (19.4) del(1)(q32)⫹ace,del(10)(q24)⫹ace,mar, mar,ace,tdic(3;?)

S20 46,XY 10/65 (15.4) 11/65 (16.9) tr(13;?)(q21;?) 2/26 (7.7) del(11)(q13.19),⫹mar S21 46,XY 8/109 (7.3) 12/109 (11.0) . . . 0/29 (0) . . . S22 46,XY 18/120 (15.0) 16/120 (13.3) . . . 4/33 (12.1) del(4)(p15.2),del(6)(q21),del(21)(q21),

banding in structural abnormalities and in chromosomal lesions in the smoker group and of the 259 breakpoints in the control group was not uniform (FIGURE2). With the exception of chro-mosome 22 in the smoker group and of chromosomes 21, 22, and Y in the control group, all other chromosomes were involved in structural abnormali-ties or in chromosomal lesions. To de-termine the possible existence of an as-sociation between the breakpoints found (at the 400-band resolution level) and those chromosome bands contain-ing fragile sites, the data on fragile sites accepted by the Committee on Hu-man Gene Mapping 11 were used.19The ttest showed a preferential location of

breakpoints in chromosome bands

con-taining fragile sites, both in smokers and in controls (P⬍.001 and P= .002,

respectively).

The fragile site multinomial method was used to identify those chromo-some bands that significantly ex-pressed breakpoints in the 2 groups. In both groups, the number of breaks re-quired to consider a band to be non-randomly affected was 4 or more. The results in the control group indicated that 12 bands were nonrandomly af-fected: 2q35, 7p15, 10q22, 11q13, and 14q24 (4 times each); 1p34, 1p22, 4q31, 6q21, and 12q13 (5 times each); and 1q32 and 17q21 (6 times each). In the smokers group, 30 bands were non-randomly affected: 1p34, 1q42, 2p13, 2p16, 2p23, 2q21, 3q21, 5q15, 6q22,

7p15, 15q24, 16q22, 16q23, and 17q23 (4 times each); 1q23, 2p21, 4q31, 6p21, 11q13, and 12q15 (5 times each); 1p36, 1q11.2, 1q32, 3p14, 7q11.2, 7q32, and 9q22 (6 times each); 11q23 (9 times, but only in smokers) (FIGURE3); 5q31 (10 times); and 17q21 (13 times) (TABLE6).

[image:7.612.56.547.323.671.2]To identify the bands with a greater propensity to break in smokers rela-tive to controls, the differences in the number of breaks for the bands listed above were calculated as described in the “Methods” section. The mean of these differences was 0.72 (SD, 1.78), with –3 and 9 the most negative and positive values. Applying the criterion of 3 SDs of the computed differences from their mean value as a classifying

Table 5.Cytogenetic Results in Amniocytes From Fetuses Carried by Nonsmoking Controls

Control Karyotype of Fetus No./Total (%) Triradials and Quadriradials Structural Abnormalities,

No./Total (%) Types of Structural Abnormalities* Aberrant

Metaphases

Cells With Gaps and Breaks

C1 46,XX 5/95 (5.3) 5/95 (5.3) . . . 0/28 (0) . . .

C2 46,XX 7/100 (7.0) 7/100 (7.0) . . . 2/27 (7.4) del(1)(q11.2)⫹ace,del(12)(q11)⫹ace

C3 46,XY 3/91 (3.3) 4/91 (4.4) . . . 0/27 (0) . . .

C4 46,XY 8/102 (7.8) 6/102 (5.9) . . . 2/31 (6.5) del(11)(q11),tdic(5;10)(q23;q21)⫹

ace(10)(q21-qter)

C5 46,XY 5/90 (5.6) 7/90 (7.8) . . . 0/27 (0) . . .

C6 46,XX 5/98 (5.1) 6/98 (6.1) . . . 1/32 (3.1) del(7)(p21)⫹ace C7 46,XX 8/94 (8.5) 13/94 (13.8) . . . 1/29 (3.4) t(1;7)(p22;p15) C8 46,XY 9/95 (9.5) 22/95 (23.2) . . . 1/24 (4.2) t(7;11)(q31;q24) C9 46,XX 6/92 (6.5) 10/92 (10.9) . . . 1/26 (3.8) del(11)(p11.1)⫹ace

C10 46,XX 16/92 (17.4) 27/92 (29.3) . . . 2/29 (6.8) del(3)(p14)⫹ace,del(11)(q14)⫹ace

C11 46,XY 8/100 (8.0) 16/100 (16.0) . . . 0/30 (0) . . .

C12 46,XX 7/123 (5.7) 6/123 (4.9) . . . 1/33 (3.0) del(10)(q22)

C13 46,XY 12/110 (10.9) 16/110 (14.5) . . . 2/31 (6.5) del(15)(q15)⫹ace,del(5)(p15.1) C14 46,XX 8/107 (7.5) 7/107 (6.5) . . . 1/28 (3.6) del(9)(q21)

C15 46,XX 13/117 (11.1) 18/117 (15.4) . . . 1/39 (2.6) del(7)(p14) C16 46,XY 12/107 (11.2) 13/107 (12.1) . . . 1/33 (3.0) t(X;1)(p22.2;q25)

C17 46,XX 8/122 (6.6) 8/122 (6.6) . . . 2/34 (5.9) der(14)t(14;17)(q32;q21),ace C18 46,XX 5/110 (4.5) 4/110 (3.6) . . . 1/29 (3.4) del(11)(p12)

C19 46,XX 9/121 (7.4) 13/121 (10.7) . . . 0/27 (0) . . .

C20 46,XY 6/112 (5.4) 8/112 (7.1) . . . 0/27 (0) . . .

C21 46,XX 12/119 (10.1) 12/119 (10.1) . . . 1/34 (2.9) mar

C22 46,XX 9/109 (8.3) 9/109 (8.3) . . . 0/27 (0) . . .

C23 46,XX 3/106 (2.8) 2/106 (1.9) . . . 1/25 (4.0) del(10)(p11.1)⫹ace

C24 46,XY 15/105 (14.3) 14/105 (13.3) qr(4;15)(q12;q15) 5/36 (13.9) del(5)(q11.2)⫹ace,del(5)(q11.2)⫹ace, del(12)(q11)⫹ace,del(6)(q23)⫹ace, del(17)(q22)⫹ace

distance, no bands with extreme nega-tive values were detected, whereas 3 bands with extreme positive values were found: 17q21 (difference, 7), 5q31 (dif-ference, 7), and 11q23 (dif(dif-ference, 9). The Fisher exact test and the nonpara-metric Wilcoxon rank-sum test reached statistical significance only for 11q23 (P= .02, both tests).

COMMENT

In this study, the main difficulty was to find heavy smokers (ⱖ10 ciga-rettes/d for ⱖ10 years) who also smoked during pregnancy, and con-trol women not exposed to tobacco at home or at work (total of 800 inter-views required). Moreover, smokers and controls had to be free of expo-sure to other clastogenic agents and not consume alcohol, coffee, or tea. In the present study it was found that, under these conditions, fetuses from preg-nant women who smoked had an creased frequency of chromosomal in-stability, evaluated by the presence of structural chromosomal abnormali-ties and chromosomal lesions.

Chromosomal instability and analy-ses of micronuclei in lymphocytes from peripheral blood have been success-fully used as biomarkers of genotoxic-ity both for assessing DNA damage at the chromosomal level and for quan-tifying early adverse human health ef-fects, in particular cancer.20,21

Periph-eral blood lymphocytes from heavy smokers (⬎30 cigarettes/d) or from children born to smokers show in-creases in structural chromosomal ab-normalities, SCEs, micronuclei, or frag-ile-site expression.7-10In utero, only

indirect data using chorionic villi have been published11,12; one study showed

an increase in SCEs while the other found no increase in chromosomal le-sions.

In our study, comparison of cytoge-netic data between groups of smokers and controls showed important differ-ences for the proportion of structural chromosomal abnormalities and to a lesser degree for the proportion of

meta-somal lesions. This propensity for a strong genotoxic effect in mothers who smoke (highest incidence of the most severe anomaly) is also observed for the chromosomal lesions, where the dif-ferences are more marked for breaks than for gaps (Table 3).

[image:8.612.226.548.195.702.2]Taking into account the way in which both groups had to be completed, ma-ternal age was by chance significantly higher in the smoker than in the con-trol group. It is well known that ma-ternal age is related to an increase in nu-merical chromosomal abnormalities

Figure 2.Distribution of Breakpoints in Amniocytes From Fetuses Carried by Mothers in the Smoker and Control Groups Displayed in the Idiogram (400-Band Resolution)

(especially trisomies and, among them, trisomy 21), but no study has related increasing maternal age to an increase in chromosomal lesions and struc-tural abnormalities. Nevertheless, 2 GEE models were considered, either in-cluding or not inin-cluding age as a co-variate. In all the analyses performed, inclusion of age as a covariate led to an increase in thePvalue of the smoking

model, those for chromosomal insta-bility (P= .04) and chromosomal

le-sions (P= .045), became nearly

signifi-cant (P=.05) and marginally influential

(P= .10), respectively, in the extended

model. The third chromosomal anomaly studied, structural chromo-somal abnormalities, remained signifi-cant in the extended model (P=.01).

Fi-nally, the analyses corresponding to a subset in which women who had be-come pregnant by in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection were excluded showed similar signifi-cance values for the smoking factor in the extended model compared with the reduced model for all 3 chromosomal anomalies studied.

It is worth noting that the maternal age factor was not significant in any of the analyses performed, suggesting that the reduced model in which this fac-tor was omitted could be more appro-priate for the description of our data. Keeping a nonsignificant covariate in an extended model can be considered adequate when this factor belongs to the

Neither of these circumstances ap-plies in the present case. As indicated above, maternal age was an observa-tional variable and it is numerical chro-mosomal abnormalities, not the anoma-lies studied in the present work, that are known to be associated with ma-ternal age. Because of these reasons, a reduced model can be more suitable than the extended model including ma-ternal age.

Our results show that fetuses ex-posed to tobacco smoke in utero have increased chromosomal instability in amniocytes, expressed as an increase of structural chromosomal abnormali-ties and chromosomal lesions, which is not influenced by maternal age. In the present study, no direct relationship be-tween the level of genotoxic tobacco compounds and chromosomal insta-bility has been demonstrated because the levels of tobacco-specific com-pounds (eg, cotinine) were not mea-sured in amniotic fluid or maternal se-rum. However, the fact that several studies have described the presence of these compounds in the blood of fe-tuses from women who smoke4-6seems

to support our findings, suggesting a possible genotoxic effect of smoking during pregnancy.

To determine if some chromosomal regions were especially affected by ex-posure of the fetus to tobacco, we local-ized the breakpoints implicated in chro-mosomal lesions and in structural abnormalities. An apparently nonran-dom distribution of breakpoints and a coincidence with fragile-site bands in the smoker and control groups was ob-served. The preferential location of breakpoints in fragile-site bands in chro-mosomal preparations from chorionic villi has been previously described.22,23

This coincidence has also been ob-served in lymphocyte chromosomes from cigarette smokers.7,24Recently,

Stein et al24and Spitz et al25have stated

that tobacco exposure increases chro-mosomal fragility due to an adaptation of DNA repair mechanisms to smok-Figure 3.Partial Metaphases of Amniocytes From Fetuses Carried by Mothers Who Smoke,

Showing Chromosomal Lesions on 11q23 Band

Fetus S19 Fetus S5 Fetus S2

Uniform (Leishman) Stain G-Band (Wright Giemsa) Stain

[image:9.612.54.379.100.330.2]Arrowheads indicate the localization of gaps (fetuses S19 and S5) and a triradial (S2).

Table 6.Expression of Chromosomal Abnormalities on the Most Affected Chromosome Bands (5q31, 11q23, and 17q21) From Fetuses Carried by Mothers Who Smoke and From Nonsmoking Controls

Band

Participant No. (No. of Abnormalities)

Smokers Controls

5q31 S2 (1), S3 (1), S5 (1), S8 (1), S11 (2), S13 (2), S16 (1), S19 (1)

C9 (1), C16 (1), C19 (1)

11q23 S2 (3), S5 (1), S14 (1), S15 (2), S19 (1), S22 (1) 17q21 S3 (1), S5 (1),

S13 (2), S15 (1), S17 (1), S18 (2), S19 (1), S21 (2), S22 (1), S25 (1)

[image:9.612.54.212.419.539.2]ineffective repair is transient and revers-ible. Several data sets suggest that to-bacco exposure induces in vivo fragile-site expression, which contributes to tumor formation.26,27

Our results show, in agreement with these studies, that tobacco exposure in-creases chromosomal instability due to late or incomplete DNA replication or to errors in repair mechanisms (ineffi-cient response or poor inducible re-pair response). Both mechanisms may affect the integrity of chromosomal structure in these regions, leading to the appearance of structural chromo-somal abnormalities, gaps, and breaks. Therefore, the chromosome break-points could produce deletions or dis-ruptions of functional genes, produc-ing developmental defects or genetic disorders, including cancer.

By comparing the breakpoint distri-bution in both groups using the frag-ile site multinomial method, 3 specific chromosome bands affected by expo-sure to tobacco have been detected: 5q31, 17q21, and, especially, 11q23. Breaks on 11q23, however, were only observed in smokers. Two of these bands, 5q31.1 and 11q23, correspond to regions where fragile sites FRA5C, FRA11B, and FRA11G are located. Ac-cording to the Committee on Human Gene Therapy,19FRA5C and FRA11G

are considered “fragile sites, aphidico-lin-type, common” and FRA11B a “frag-ile site, folic acid-type, rare.” In this sense, it should be noted that smokers have reduced concentrations of folic acid in serum,28 a fact that could

ex-plain the high incidence of break-points at 11q23.

It is worthwhile to note that chro-mosome breaks at 3p14.2, where the most common fragile site (FRA3B) is located, were only found in mothers who smoke (6 times). Although in the present study this site was not among the 3 breakpoints most expressed in amniocytes from fetuses of mothers who smoke (more than 8 lesions each), this finding is consistent with that of a previous study24in which FRA3B

ex-It has been suggested that the in-crease of chromosomal lesions and structural abnormalities or the very existence of an increased chromo-somal instability resulting from the genotoxic effect of tobacco could be in-dicative of an increased cancer risk and that fragile sites could be responsible for the chromosomal instability ob-served in cancer cells.27Moreover, an

increase of chromosomal instability is associated with an increase in the risk of cancer, especially childhood malig-nancies.29

For the last 30 years, consumption of tobacco by parents has been related to leukemia in infancy.2,30It is known that

a high proportion of infants (40%-60%), children (18%), and adults (3%-7%) with leukemia have molecular re-arrangements in chromosome band 11q23, but these rearrangements are not always detectable by cytogenetic analy-sis.31-34According to some authors,31-35

there is strong evidence that 11q23 re-arrangements occur in utero. These find-ings show the importance of the involve-ment of band 11q23 in events leading to leukemogenesis in infants. The other 2 bands most affected by tobacco in our study (5q31 and 17q21), although not affected in statistically significant pro-portions, are also involved in child-hood leukemia.34

In conclusion, maternal smoking of 10 or more cigarettes per day for 10 or more years, including during preg-nancy, is associated with increased chromosomal instability in amnio-cytes. Band 11q23, which seems to be especially sensitive to compounds con-tained in tobacco, is known to be in-volved in leukemogenesis. This band contains the genesATM(cell

prolym-phocytic leukemia),PLZF(leukemia

acute, promyelocytic;PLZF/RARAtype),

and MLL (leukemia,

myeloid/lym-phoid, or mixed lineage). Thus, the transplacental exposure to tobacco could be associated with an increased risk of pediatric hematopoietic malig-nancies. Epidemiologic studies will be needed to determine whether the

off-Author Contributions:Dr Egozcue had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design; analysis and interpreta-tion of data:de la Chica, Giraldo, Egozcue, Fuster.

Acquisition of data:Ribas.

Drafting of the manuscript:de la Chica, Ribas, Giraldo, Egozcue, Fuster.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important in-tellectual content; study supervision:Giraldo, Egozcue, Fuster.

Statistical analysis:Giraldo.

Obtained funding:Fuster.

Administrative, technical, or material support:de la Chica, Ribas.

Financial Disclosures:None reported.

Funding/Support:Financial support for this study was provided by the Comissionat per a Universitats i Re-cerca (2001, SGR-00201).

Role of the Sponsor:The Comissionat per a Univer-sitats i Recerca was not involved in the design and con-duct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and in-terpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Previous Presentation:Preliminary results of this study were presented at the Third European Cytogenetics Conference; July 7-10, 2001; Paris, France. Acknowledgment:We thank the Department of Ob-stetrics and Gynecology, Institut Universitari Dexeus and the Centro de Patología Celular for their kind col-laboration in providing the samples.

REFERENCES

1.Vogler GP, Kozlowski LT. Differential influence of maternal smoking on infant birth weight: gene-environment interaction and targeted intervention.

JAMA. 2002;287:241-242.

2.Ji BT, Shu XO, Linet MS, et al. Paternal cigarette smoking and the risk of childhood cancer among off-spring of nonsmoking mothers.J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:238-244.

3.Jalili T, Murthy GG, Schiestl RH. Cigarette smoke induces DNA deletions in the mouse embryo.Cancer Res. 1998;58:2633-2638.

4.Lackmann GM, Salzberger U, Tollner U, et al. Me-tabolites of a tobacco-specific carcinogen in urine from newborns.J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:459-465. 5.Jauniaux E, Gulbis B, Acharya G, et al. Maternal tobacco exposure and cotinine levels in fetal fluids in the first half of pregnancy.Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93: 25-29.

6.Milunsky A, Carmella SG, Ye M, et al. A tobacco-specific carcinogen in the fetus.Prenat Diagn. 2000; 20:307-310.

7.Ban S, Cologne JB, Neriishi K. Effect of radiation and cigarette smoking on expression of FUdR-inducible common fragile sites in human peripheral lymphocytes.Mutat Res. 1995;334:197-203. 8.Pluth JM, Ramsey MJ, Tucker JD. Role of mater-nal exposures and newborn genotypes on newborn chromosome aberration frequencies.Mutat Res. 2000; 465:101-111.

9.Rowland RE, Harding KM. Increased sister chro-matid exchange in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of young women who smoke cigarettes.Hereditas. 1999;131:143-146.

10.Littlefield LG, Joiner EE. Analysis of chromosome aberrations in lymphocytes of long-term heavy smokers.Mutat Res. 1986;170:145-150.

deoxyribo-ing in early pregnancy observed on chromosome ab-errations in chorionic villus samples.Mutat Res. 1993; 298:285-289.

13.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis us-ing generalized linear models.Biometrika. 1986;73:13-22.

14.Böhm U, Dahm PF, McAllister BF, et al. Identify-ing chromosomal fragile sites from individuals: a mul-tinomial statistical model.Hum Genet. 1995;95:249-256.

15.Greenbaum IF, Fulton JK, White ED, et al. Mini-mum sample sizes for identifying chromosomal frag-ile sites from individuals: Monte Carlo estimation.Hum Genet. 1997;101:109-112.

16.Stokes ME, Davis CE, Koch GG.Categorical Data Analysis Using the SAS System. 2nd ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2000.

17.Price PJ. Chromosome abnormalities in amniotic fluid cells in culture.Karyogram. 1988;14:10-11. 18.Kerber S, Held KR. Early genetic amniocentesis: 4 years’ experience.Prenat Diagn. 1993;13:21-27. 19.Human Gene Mapping 11: London Conference (1991): Eleventh International Workshop on Human Gene Mapping: London, UK, August 18-22, 1991. Cy-togenet Cell Genet. 1991;58:1-984.

20.Musthapa MS, Lohani M, Tiwari S, et al.

Cyto-biofuels: micronucleus and chromosomal aberration tests in peripheral blood lymphocytes.Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;43:243-249.

21.Norppa H. Cytogenetic biomarkers.IARC Sci Publ. 2004:179-205.

22.Miguez L, Fuster C, Pérez MM, et al. Spontane-ous chromosome fragility in chorionic villus cells.Early Hum Dev. 1991;26:93-99.

23.Caporossi D, Vernole P, Nicoletti B, et al. Char-acteristic chromosomal fragility of human embryonic cells exposed in vitro to aphidicolin.Hum Genet. 1995; 96:269-274.

24.Stein CK, Glover TW, Palmer JL, et al. Direct cor-relation between FRA3B expression and cigarette smoking.Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;34:333-340.

25.Spitz MR, Wei Q, Dong Q, et al. Genetic suscep-tibility to lung cancer: the role of DNA damage and repair.

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:689-698. 26.Glover TW. Instability at chromosomal fragile sites.

Recent Results Cancer Res. 1998;154:185-199. 27.Richards RI. Fragile and unstable chromosomes in cancer: causes and consequences.Trends Genet. 2001;17:339-345.

28.Anderson D, Zeiger E. Human monitoring. Envi-ron Mol Mutagen. 1997;30:95-96.

some fragility and predisposition to childhood malignancies.Anticancer Res. 1998;18:2359-2364. 30.Sasco AJ, Vainio H. From in utero and childhood exposure to parental smoking to childhood cancer: a possible link and the need for action.Hum Exp Toxicol. 1999;18:192-201.

31.Chen CS, Sorensen PH, Domer PH, et al. Mo-lecular rearrangements on chromosome 11q23 pre-dominate in infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia and are associated with specific biologic variables and poor outcome.Blood. 1993;81:2386-2393.

32.Pathology and genetics of tumours of haemato-poietic and lymphoid tissues. In: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, eds.World Health Organiza-tion ClassificaOrganiza-tion of Tumors. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2001:86.

33.Cox MC, Panetta P, Lo-Coco F, et al. Chromo-somal aberration of the 11q23 locus in acute leuke-mia and frequency of MLL gene translocation: re-sults in 378 adult patients.Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122: 298-306.

34.Hall GW. Childhood myeloid leukaemias.Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2001;14:573-591.

35.Ford AM, Ridge SA, Cabrera ME, et al. In utero rearrangements in the trithorax-related oncogene in infant leukaemias.Nature. 1993;363:358-360.

The greatest test of courage on earth is to bear defeat without losing heart.

Departament de Biologia Cel·lular, Fisiologia i Immunologia de la

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona,

ESTUDIO CITOGENÉTICO

EN AMNIOCITOS

DE GESTANTES FUMADORAS

El Dr. Josep Egozcue Cuixart y la Dra. Carme Fuster Marqués del

Departament de Biologia Cel·lular, Fisiologia i Immunologia de la

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona,

CERTIFICAN

Que Rosana de la Chica Díaz ha realizado, bajo su dirección, el

trabajo titulado “

Estudio citogenético en amniocitos de gestantes

fumadoras”

Este trabajo se ha realizado en la Unitat de Biologia Cel·lular i

Genètica Mèdica de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallés), noviembre de 2005

A J ordi

¡M ira este día! Pues es la vida, la propia vida de la vida.

especial a las siguientes:

A Josep Egozcue, a quién profeso una gran admiración, ya que confió en mí y en la idea de esta tesis, permitiendo que me integrase en su equipo de investigación. Por su interés, paciencia, comprensión, y por su aportación inestimable, tanto a nivel profesional como humana, sin cuya dirección no habría sido posible la realización de esta tesis.

A Carme Fuster, por ser la codirectora de esta tesis, por todo lo que he aprendido de ella, por su enorme paciencia y por su gran colaboración.

A Isabel Ribas, por facilitarme las muestras del estudio, por colaborar desde principio a fin de este trabajo y por estar siempre dispuesta a darme una mano.

A la Unidad de Biología Cel·lular i Genètica Humana de la Facultad de Medicina de la UAB por acogerme y permitirme llevar a cabo este estudio.

Y sobre todo a los profes de la Unitad , por su profesionalidad y afecto que me han demostrado en todos estos años: A Rosa Miró , a Joaquina Navarro por su gran amistad , a Jordi Benet, Cristina Templado, a Montse Garciá por nuestras charlas sobre plantas y otras cosas....

Al Centro de Patología Celular y Diagnóstico Prenatal (CPC) por facilitar las muestras del presente estudio. Especialmente quiero agradecer la colaboración de la Secretaria: Elisabeth Miras, a Begoña Méndez y a Marta Carrera.

A la Generalitat de Catalunya por la financiación otorgada a nuestro grupo de investigación (2001, SGR-00201).

A Alberto Plaja, por confiar siempre en mí, y a todos los compañeros del Valle d’Hebron ya que en momentos difíciles para mi supieron apoyarme y animarme para seguir luchando en todos los ámbitos

A Jesús Giraldo, por su soporte estadístico, su ayuda en la elaboración de los resultados y por la constancia que ha mostrado en todo momento.

A los colegas del Departamento de Hematología de la Dra. Woessner y el Dr. Francesc Solé.

A los compañeros del laboratorio:

Javier , Nuria Camats , Mery, Montse Codina (por sus ayudas con el Photoshop) , Bea, Pedro, Raquel , Vanesa, Ana , Yolanda (por sus consejos), Pere Puig, Angels Niubó (por todo su apoyo técnico y especialmente con el colorante Wright) y Anna Utrabo.

A los compañeros de Ciencias: Laura Latre, Nuria Arnedo, Marta Martí.

A mis compañeros de la reunión de bibliografía por sus enseñanzas y su sugerencias a lo largo de muchos y muchos años, ya desde la casa de Alberto con los zumos de Veneranda .

Al Dr. Costa-Jussa, quien me dio muchos ánimos para la realización de este proyecto.

A mis padres, sobre todo a mi padre por la confianza y porque fue él quién me animó a la realización de esta tesis.

A mis hermanos Javier y Marian, y a todos mis sobrinos: Ricard, por sus ayudas informáticas, Daniel, Julia, Gemma , Elisa y Berta.

Y sobre todo a Jordi, por su paciencia, por soportar y aguantar todas mis “ neuras” y porque sin él no hubiese terminado mi tesis doctoral.

Supongo que hay gente que no he nombrado pero que merecen mi agradecimiento.

Muchas Gracias a todos

INDICE

1.- INTRODUCCIÓN... 1

1.1 Consumo del tabaco: efecto sobre la salud... 1

1.1.1 Componentes del humo del tabaco... 6

1.2 Mutagénesis... 10

1.2.1 Anomalías cromosómicas... 11

1.2.1.1 Anomalías numéricas... 12

1.2.1.2 Anomalías estructurales... 12

1.2.1.2.1 tipo cromosoma... 13

1.2.1.2.2 tipo cromátide... 20

1.3 Lugares frágiles... 27

2.- OBJETIVOS... 29

3.- MATERIAL Y MÉTODOS... 31

3.1 Origen y características de la serie analizada... 31

3.2 Material de laboratorio... 36

3.3 Metodología experimental... 37

3.3.1 Técnica de cultivo y obtención de preparaciones... 37

3.3.2 Técnicas de identificación cromosómica... 39

3.4 Análisis al microscopio... 42

3.5 Análisis estadístico... 43

3.5.1 Modelo de ecuaciones estimado generalizado (GEE)... 43

4.1 Puesta a punto de la técnica Uniforme-Bandas G a partir de extensiones

de amniocitos realizadas previamente con fines diagnósticos... 47

4.2 Resultados citogenéticos... 50

4.2.1 Análisis de las metafases aberrantes... 50

4.2.2 Análisis de la inestabilidad cromosómica... 51

4.2.3 Análisis de los resultados citogenéticos obtenidos en relación a las características de las muestras... 57

4.2.4 Frecuencia de roturas cromosómicas por banda... 63

4.2.5 Bandas cromosómicas preferentemente afectadas... 64

4.2.6 Relación entre las bandas cromosómicas preferentemente afectadas y bandas donde se localizan lugares frágiles... 67

4.2.7 Regiones cromosómicas especialmente afectadas por el efecto genotóxico del tabaco... 68

5.- DISCUSIÓN... 71

5.1 Característica de la serie analizada... 71

5.2 Efecto genotóxico del tabaco... 73

5.2.1 Regiones cromosómicas especialmente afectadas por el consumo del tabaco... 76

5.2.2 Relación entre el incremento de la inestabilidad cromosómica, las regiones cromosómicas especialmente afectadas por la exposición al tabaco y cáncer... 79

6.- CONCLUSIONES... 89

7.- BIBLIOGRAFÍA... 91

8.- ANEXOS... 119

8.1 Encuesta... 119

1

1

-

-

I

I

N

N

T

T

R

R

O

O

D

D

U

U

C

C

C

C

I

I

Ó

Ó

N

N

1

11...111...---CCCooonnnsssuuummmooodddeeellltttaaabbbaaacccooo:::eeefffeeeccctttooosssooobbbrrreeelllaaasssaaallluuuddd

El tabaco (“Nicotiana tabacum”) es una planta originaria de América que

crece en climas húmedos y con temperaturas que oscilan entre los 18 y los 22 ºC

(Fig.1).

FIGURA 1. Hojas de Nicotiana tabacum

Fue utilizada por los indios amazónicos dentro de un contexto cultural

con fines mágico–religiosos y curativos. En 1492 al descubrir el Nuevo Mundo,

Colón no le dio mucha importancia al tabaco. Sin embargo, algunos de sus

acompañantes, empezando por Rodrigo de Jerez, cayeron rápidamente en el

hábito de fumar. Este hábito más adelante fue adquirido por los conquistadores

y después por los colonizadores y así, poco a poco, se fue introduciendo en

España y Portugal, y después progresivamente en Europa.

Hasta el siglo XIX la mayor parte del tabaco consumido era masticado o

fumado en forma de cigarros o en pipa. Por el contrario, el consumo de

cigarrillos es la forma predominantede consumo de tabaco desde los inicios del

consumo se deben, fundamentalmente, a la invención de máquinas

manufacturadoras de cigarrillos a finales del siglo XIX, incluso de tipo

doméstico, y la publicidad a gran escala de estos productos a partir de los

primeros años del siglo XX. Estos cambios en los patrones de consumo han

tenido importantes implicaciones sobre la salud.

Según el informe de la “European Actions on Smoking in

Pregnancy”(http://www.famp.es/famp/programas/euroscip/textospdf/INF

ORMEEESP) en la actualidad el 36% de la población adulta española es

fumadora y un 13% exfumadora, lo cual da una idea de la magnitud del

problema.

El cigarrillo es la forma de consumo de tabaco que goza de mayor

popularidad y aceptación (emboquillados o sin filtro, rubios y negros, light,

semilights o enteros). Le siguen, bastante por detrás, en cifras de consumo el

cigarro puro, la pipa y dos modalidades conocidas como “tabaco sin humo“: el

rapé (tabaco en polvo que se inhala), el tabaco de mascar y actualmente el

tabaco de hierbas (O’connor y col., 2005; Soldz y Dorsey, 2005)

Aunque todo consumo de tabaco conlleva serios riesgos para la salud,

cualquiera que sea el tipo que se consuma, es importante tener en cuenta que

hay diferencias significativas entre un tipo y otro, tanto desde el punto de vista

de la toxicidad como de la adicción. Si nos centramos en el tabaco fumado, el

riesgo es mayor cuanto mayor sea el número de cigarrillos consumidos, más

años se lleve fumando y más elevado sea el contenido de alquitranes y nicotina

de cada cigarrillo. Este último factor depende, de la forma de cultivo, el

momento de cosecha, el tipo de curado, la fermentación y la clase de aditivos.

Según los datos que maneja la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS),

el tabaquismo es hoy la epidemia más peligrosa en la humanidad después del

Sida ya que en todo el mundo se producen seis muertes por minuto por esta

personas fuman, es decir, el 18,3% de la población y se estima que de ellos

fallecerán 9 millones de aquí al año 2020, (de Seixas Correa, 2002)

Entre las principales consecuencias en la salud del individuo que

consume regularmente tabaco, Fig.2, se encuentran: incremento del riesgo de

problemas de coagulación, cardiovasculares, enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva

crónica, cáncer y efectos adversos en el embarazo (Petersen, 2003; Zdravkovic y

col., 2005;)

Otra consecuencia importante del hábito de fumar es que en los hombres

se observa una reducción en el recuento espermático, que es proporcional al

consumo de tabaco, y también se ha observado que es más probable encontrar

espermatozoides anormales, con un cromosoma Y extra, en jóvenes de 18 años

de edad (Rubes y col., 1998).

A pesar de la publicidad advirtiendo las consecuencias perjudiciales del

consumo de tabaco en la salud existe un elevado porcentaje de mujeres que

fuman. En general, el hábito de fumar ha sido siempre más común entre la

población masculina. Sin embargo, la diferencia entre géneros empezó a

disminuir hacia mediados de la década de los ochenta y se ha mantenido casi

invariable hasta hoy. En 1998, dicho consumo alcanzó el 22% de la población

femenina (Baumert y col., 2005). Según un estudio, reciente del Hospital Carlos

III, en España el porcentaje de mujeres que continúan fumando durante el

a

[image:23.595.116.423.145.585.2]b

FIGURA 2. Principales consecuencias del consumo del tabaco en la salud:

a) mortalidad debida al consumo de tabaco; b) diferentes tipos de cáncer que

pueden padecer los individuos que fuman.

Department of Health & Human Services, USA, 2004

Mujeres y hombres comparten los mismos riesgos de padecer

enfermedades respiratorias, circulatorias y cánceres a consecuencia del tabaco

pero además, en las mujeres fumar constituye un riesgo añadido para su

descendencia.

Las mujeres embarazadas que fuman cigarrillos tienen un mayor riesgo

de tener problemas de coagulación, placenta previa, infertilidad, niños nacidos

muertos (Desurmont, 2005), prematuros o con bajo peso al nacer (Wang y col.,

2002). Además, existe un mayor riesgo de tener abortos espontáneos

(Cnattingius, 2004). Dependiendo de la cantidad de cigarrillos, la disminución

de peso del recién nacido puede llegar a alcanzar hasta los 500 gramos ya que el

tabaco cambia las condiciones del desarrollo del feto (Vogler y Kozlowski, 2002).

El aumento del riesgo de alteraciones en el crecimiento físico no es lo

único que puede afectar a estos niños ya que también se han descrito

alteraciones en su desarrollo mental. Dichos trastornos pueden manifestarse

tanto a medio como a largo plazo, pudiendo llegar a constituir trastornos graves

de salud, ya que incluso pueden acabar en procesos cancerosos durante la

infancia o la adolescencia. (Stjernfeldt y col., 1986; Sasco y Vainio,1999).

Recientemente, se ha descrito que estos niños pueden desarrollar trastornos de

la conducta (Laucht y Schmidt, 2004; Gray y col., 2004).

Se conocen como fumadores pasivos aquellas personas, que a pesar de

no consumir tabaco, están en contacto directo con el humo del cigarrillo.

Cuando se fuma delante de otras personas se les está convirtiendo en

“fumadores pasivos” al obligarles a respirar un aire contaminado con el humo

que el fumador expulsa y el que genera el cigarrillo. A modo informativo, el

humo de un cigarrillo emana dos veces más alquitrán y nicotina que lo inhalado

por el fumador. Por ello el nivel de monóxido de carbono en la sangre de los no

(Husgafvel-En los últimos años se han llevado a cabo un elevado número de estudios

en fumadores pasivos ( Diethelm y col., 2005 ,;Nazaire, 2005). Cerca del 65% de

estos individuos evidencian trastornos directamente derivados del efecto nocivo

del tabaco. Las investigaciones de la Agencia de Protección del Medio Ambiente

en California (EPA) llevadas a cabo en 1997 avalaron la existencia de una

relación entre tabaquismo pasivo y la aparición de cáncer o de enfermedades

cardíacas. (Jinot y Bayard, 1994; Cardenas y col., 1997)

Resulta interesante mencionar la actitud contradictoria en la legislación

incluso de los países más adelantados. Mientras existen leyes gubernamentales

sobre el control alimentario que prohíben la utilización de aditivos

carcinogénicos, tanto en los alimentos para personas como para animales, no

existe una legislación similar con el cigarrillo. Sin embargo, afortunadamente se

están realizando cambios, principalmente en la publicidad, encaminados a

alertar al consumidor de los peligros que el tabaco produce en la salud.

Por último indicar que los cigarrillos se fabrican para crear dependencia

entre sus consumidores; el cigarrillo es la droga que con más asiduidad se

consume. Nadie se droga cada 25 minutos; el fumador si.

1

11...111...111...---CCCooommmpppooonnneeennnttteeesssdddeeelllhhhuuummmooodddeeellltttaaabbbaaacccooo

Los efectos nocivos del tabaco sobre el organismo dependen de las

sustancias químicas contenidas en la hoja del tabaco, precursoras de los

productos que aparecerán en el humo tras su combustión. Principalmente son:

la nicotina, el monóxido de carbono, los gases irritantes, y las sustancias

cancerígenas (Brunnemann y Hoffman, 1991; Jalili y col., 1998).

Prácticamente la totalidad del consumo actual se realiza mediante la

inhalación de la combustión de los productos del tabaco. Las diferentes regiones

del cigarrillo muestran distinta toxicidad (Fig.3). En el extremo del cigarrillo que

reacciones químicas que dificultan la identificación completa de todas las

sustancias que existen o se generan en el proceso de fumar.

La composición del humo de la calada depende del tipo de tabaco y de

múltiples factores como la profundidad de la inhalación, la temperatura de

combustión, la longitud del cigarrillo, la porosidad del papel y la presencia de

aditivos y filtros (Simon y col., 2005 ; Torikaiu y col., 2005).

La concentración de sustancias tóxicas es mayor a medida que se dan

pipadas al cigarrillo, hasta alcanzar en la última calada el doble que en la

primera. Hasta ahora se han reconocido cerca de 4.000 elementos químicos

presentes en la fase gaseosa y la sólida o en las partículas del humo del tabaco

(Brunnemann y Hoffmann, 1991)

La composición de la corriente principal que aspira el fumador es

bastante diferente de la secundaria que se escapa del cigarrillo al ambiente.

Muchas sustancias nocivas presentes en el humo están más concentradas en esta

corriente secundaria (monóxido y dióxido de carbono, amoniaco, benceno,

benzopireno, anilina, acroleína y otros muchos), lo que incrementa la toxicidad

de la atmósfera que genera (Hecht, 1999) (Tabla 1)

La mayoría de los efectos perjudiciales del humo de tabaco se deben a la

presencia de monóxido de carbono, óxidos de nitrógeno, amoniaco, ácido

cianhídrico y acroleína, entre otras sustancias (Surgeon General of the US 1979)

(Tabla 2).

TABLA 1. Principales sustancias químicas cancerígenas del humo del tabaco

Compuestos químicos genéricos Cancerígeno

Hidrocarburos policíclicos aromáticos Benzo (a) pireno

Benzo (b) fluoranteno

Benzo (f) fluoranteno

Benzo (k) fluoranteno

Dibenzo (a,i) pireno

Indeno (1,2,3-cd)

Antraceno

5-metilcriseno

Aza-arenos Dibenzo (a,h) acridina

7H- Dibenzo(c,f)carbazole

N- nitosaminas N- nitrosodietilamina

4- Metilnitrosamino -1-

(3-piridil-1-butanona)(NNK)

Compuestos orgánicos 1, 3,-Butadieno

Etil-carbonato

Compuestos inorgánicos Níquel

Cromo

Cadmio

Polonio-210

TABLA 2. Cantidad de los principales componentes presentes en el humo del

un cigarrillo

Principales componentes presentes en las partículas del humo del cigarrillo

Componente Concentración media por cigarrillo

Alquitrán 1-40 mg

Nicotina 1-2.5 mg

Fenol 20-150 mg

Catecol 130-280 mg

Pireno 50-200 mg

Benzo (a) pireno 20-40 mg

2.4 Dimetilfenol 49 mg

m- y p-Cresol 20 mg

p-Etilfenol 18 mg

Sigmasterol 53 mg

Fitosteroles (total) 130 mg

Alquitrán: Este componente es el de mayor grado tóxico, y está

constituido por más de 500 substancias distintas. Es irritante y cancerígeno

Nicotina: Es un alcaloide que induce la liberación de adrenalina,

noradrenalina y dopamina y a través de la acción sobre el Sistema Nervioso

Central, es la causante de la dependencia psíquica produciendo adicción del

fumador al consumo del tabaco. La cantidad que absorbe un individuo varía

con la intensidad de la inhalación; generalmente solo absorbe un 30% del

fuma en espacios cerrados, los no fumadores se convierten en fumadores

pasivos pues inhalan el humo presente en el ambiente.

También tiene un efecto vasoconstrictor, que afecta a distintos órganos

centrales, especialmente el corazón, a través de las arterias coronarias. El tabaco

también produce vasoconstricción de los vasos de la placenta de la mujer

embarazada, cuya función principal es el intercambio de oxígeno y nutrientes

con el feto, viéndose afectado éste en el desarrollo (peso y talla inferiores a lo

normal), y también por la acción de metales pesados inhalados por la madre,

que pasan al torrente circulatorio del feto (Gomolka y col., 2004)

. .

M onóxido de carbono: Es un gas que procede de la combustión

incompleta del tabaco. Este compuesto tiene la particularidad de competir con el

oxigeno en su combinación con la hemoglobina, pero al tener una afinidad 300

veces superior, forma un compuesto, la carboxihemoglobina, que no es útil para

la respiración celular al bloquear el transporte de oxígeno. Este efecto, sumado a

la vasoconstricción coronaria que da la nicotina, justifica la relación del hábito

de fumar y la aparición de accidentes coronarios.

Sustancias cancerígenas: En el humo del tabaco se han detectado

diversas sustancias cancerígenas, como el benzopireno, que se forman durante

la combustión del tabaco o del papel de los cigarrillos (IARC, 1986)

Recientemente, DeMarini (2004) ha publicado una revisión en la que se

evidencia el efecto genotóxico del tabaco en distintos tejidos en fumadores.

1

11...222...---MMMuuutttaaagggééénnneeesssiiisss

El ADN es una molécula con una gran estabilidad que, mediante la

replicación, es capaz de transmitir la información genética que contiene a las

mutaciones, siendo hereditarios, ya que la célula los trasmitirá a sus células

hijas.

Muchos carcinógenos químicos pueden ser activados metabólicamente, al

interaccionar con moléculas intracelulares, y producir daño genético.

Recientemente, diversos autores han detectado la presencia de metabolitos

específicos del tabaco en la orina de recién nacidos de gestantes fumadoras y de

gestantes fumadoras pasivas (Lackmann y col., 1999; Jauniaux y col., 1999;

Milunsky y col., 2000) lo que sugiere un posible efecto genotóxico en etapas

tempranas del desarrollo embrionario. Entre estas sustancias químicas se

encuentran:

NNAL: 4-(metilnitrosamino)- 1-(3-piridil)-1-butanol

NNAL-Gluc: 4-[(metilnitrosamino)-1-(3-piridil)but-1-yl]

β-O-D- ácido glucosidurónico

1

11...222...111...---AAAnnnooommmaaalllíííaaassscccrrrooommmooosssóóómmmiiicccaaasss

La mayoría de los agentes mutagénicos y carcinogénicos (clastogénicos)

producen daños en el ADN que conducen a roturas cromosómicas y por tanto a

la aparición de aberraciones cromosómicas. Por tanto, las aberraciones

cromosómicas que se llegan a observar mediante microscopia óptica son el

producto final de una larga cadena de acontecimientos. Estos agentes

clastogénicos son capaces de producir aberraciones cromosómicas a lo largo de

diferentes fases del ciclo celular (G1, S, G2) y difieren entre si por el daño

ocasionado ya sea a nivel cuantitativo como cualitativo.

Cualquier variación en el número básico o en la morfología de los

cromosomas de un individuo constituye una anomalía cromosómica. Las

aberraciones cromosómicas pueden clasificarse en dos grandes grupos: Si el

número total de cromosomas difiere de la dotación numérica normal (anomalías

numéricas) o si la morfología, de uno o más cromosomas, ha sido afectada