INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH ON AGGRESSION AND VIOLENCE

Risk Factors for Child-to-Parent Violence

Izaskun Ibabe&Joana Jaureguizar& Peter M. Bentler

Published online: 25 May 2013

#Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013

Abstract One of the goals of the present work was to study the relationship between child-to-parent violence (CPV) and other types of intra-family violence such as inter-parental violence and parent-to-child violence, in order to verify which of these two types of domestic violence is a more relevant risk factor for CPV and to analyze the presence of gender differ-ences in the bi-directionality of violence. Another purpose was to identify the psychological profile of perpetrators. The sample comprised 485 adolescents from the province of Gipuzkoa (Spain), of both sexes, taken from nine schools and aged 12 to 18. Parent-to-child violence and inter-parental violence were significant risk factors for CPV. Evidence was found in support of a social learning taking into account gender: boys were more likely to be physically aggressive toward the mother if she was also physically victimized by the father. Differences were found in the pro-files of adolescents who behave violently toward their parents (inappropriate upbringing by mother, social maladjustment, and drug abuse) depending on gender.

Keywords Child-to-parent violence . Adolescents . Family violence . Maladjustment . Gender differences

Violence against parents is understood to be any act by a child to gain power and control over parents by causing them physical, psychological, emotional or financial harm (Cottrell2001). Following Cottrell’s (2001) definition, psy-chological abuse occurs when children intimidate the parent, making him or her fearful while emotional abuse refers to making the parent think he or she is insane, making manipu-lative threats (such as threatening to run away, commit suicide or otherwise hurt themselves without really intending to do so) and controlling the running of the household. Child-to-parent violence (CPV) is a phenomenon that has become high-profile in recent years, though there appears to be little support or potential for intervention available, compared to cases of other types of family violence. It is difficult to provide data on the prevalence of parent abuse because of the secretive nature of this phenomenon as well as to the methodology used (quantitative vs. qualitative studies) and the sample stud-ied (community sample, clinical sample, court data or age of the aggressors). In the United States, rates of aggression toward parents range between 7 % and 29 %, but in Canada and France the rates are slightly lower (see reviews by Gallagher 2008, and Kennair and Mellor2007). There, this study focuses on the current family dynamics and the psycho-logical characteristics of adolescents, in order to throw some light on this kind of family violence. Moreover, this study aims to compare and contrast the risk factors found in a general population with those found in clinical or legal-based data sets.

Perpetrators and Victims: Gender Differences

Previous research on parent abuse (based on the evidence from clinical or legal samples) indicates that the majority of aggressors are males aged between 10 and 18 who attack Author Note This research was supported by a grant from the

University of the Basque Country, Spain (EHU06/95) to the first and second authors. The first author would like to thank the Department of Psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, for their hospitality during her sabbatical visit, which greatly facilitated the completion of this manuscript.

I. Ibabe (*)

Department of Social Psychology and Behavior Sciences Methodology, University College of Psychology, University of the Basque Country, Avda. Tolosa 70, 20018 Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain

e-mail: izaskun.ibabe@ehu.es J. Jaureguizar

University College of Teaching Training, University of the Basque Country, Lejona, Spain

P. M. Bentler

their mothers, mainly in one-parent families (Agnew and Huguley 1989; Ibabe and Jaureguizar 2010; Kethineni 2004; Paulson et al. 1990; Walsh and Krienert 2007, 2009). A recent meta-analysis of a total sample of 3,660 young people identified by parents or researchers as violent toward their parents found that 72 % of these juveniles (2,609) were boys (Gallagher2008). However, other authors report similar percentages of son and daughter aggressors (McCloskey and Lichter 2003; Stewart et al. 2005). According to Pagani et al. (2004) and Gallagher (2008), gender differences in parent abuse depend on the kind of research methodology used with clinical, anecdotal and forensic studies finding more son perpetrators, and epide-miological studies finding no sex differences. The available evidence does suggest sex differences in CPV, insofar as sons are more likely to be physically abusive toward their parents, while daughters are more likely to be emotionally and verbally abusive (Evans and Warren-Sohlberg 1988; Nock and Kazdin 2002). For this reason, sons might be more likely to be referred to clinical or law services.

As for the victims of CPV, most studies agree unequivo-cally that mothers are far more often the victims of abuse from their children. However, the methodology used to gather the data must be taken into account. On the one hand, research based on community samples using adolescent and parent self-reports show small differences between the number of father and mother victims (Gallagher2008). On the other hand, survey research shows differences in victimization depending on the severity of violence. Cornell and Gelles (1982) found mothers reported being the victims of their child’s violence slightly more than fathers (11 % versus 8 %), but when the violence was severe it was five times more commonly aimed at mothers (5 % to 1 %). Gallagher (2008) concludes that when parents are the respondents in survey studies and only severe violence is taken into account, the gender ratio of parent victims (i.e., about 80 % of mothers) is fully consistent with the clinical and court evidence. According to social learning theory, a possible explanation for mothers being the most frequent victims of their children’s violence may be the modeling the child receives from seeing the father abusing the mother. Another factor may be that the child grew up with disrespectful or derogatory beliefs about women, and learned to see violent and abusive behaviors toward the mother as acceptable (Gelles and Straus 1988; Howard1995).

Bi-Directionality of Family Violence

The link between growing up in a violent family context and subsequent parent abuse is becoming increasingly highlighted in the literature on this issue (Kennedy et al.2010; Maxwell and Maxwell2003; Pagani et al.2009). In any case, a distinction

should certainly be drawn between two kinds of family vio-lence and their influence on child-to-parent aggression: inter-parental violence and parent-to-child violence.

Inter-parental violence has been identified in some stud-ies as a decisive factor for future son-to-mother violence (e.g., Cottrell and Monk 2004; Ulman and Straus 2003), even when controlling for young people’s externalizing symptoms (Boxer et al.2009). In a recent study, Boxer et al. (2009) found a linear relationship between family ag-gression and CPV in their clinically-referred sample. When there was neither inter-parental violence nor parent-to-child violence, only 25 % of young people exhibited CPV, but when inter-parental and parent-to-child aggressions were reported, 75 % exhibited CPV. According to social learning theory, early childhood experiences and parent-child rela-tionships, such as witnessing abuse and the effects of dif-ferent parenting styles and abuse within the home, influence later behavior patterns (Downey1997). Children learn how to behave by witnessing interparental abuse and by experiencing violent behavior from their parents. Results from studies targeting gender differences in the influence of inter-parental violence on CPV indicate that daughters who witness parental aggression are less likely than sons to be violent toward their parents (Langhinrichsen-Rohling and Neidig1995).

Boxer et al. (2009) reported evidence in support of the idea that young people are likely to learn to behave aggressively from their same-sex parent. They observed that young people were more likely to be physically abusive toward an opposite-sex parent, if that parent also was victimized physically by the same-sex parent (e.g., boys would be more likely to aggress physically against his mother, if his mother was victimized physically by his father).

In the case of parent-to-child violence, many studies sug-gest the hypothesis of the bi-directionality of family violence as an explanation for child-to-parent aggression: those chil-dren who abuse their parents are more likely to have previ-ously suffered violence from their parents (Boxer et al.2009; Langhinrichsen-Rohling and Neidig 1995; Mahoney and Donnelly2000; Straus and Hotaling1980). This would be in the line of the coercion theory explained by Patterson and colleagues (Granic and Patterson2006; Patterson1982,1986; Patterson et al.1984), which suggests that CPV is a logical outgrowth of earlier hostile and aggressive interactions be-tween parents and children. The influence of harsh punish-ment of children by parents has raised the question of the importance of parenting styles for the development of violent behaviors in children.

Parenting Styles

children and includes four parenting styles: authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and uninvolved (Baumrind1991), with two main dimensions: parental responsiveness (paren-tal warmth or supportiveness) and degree of paren(paren-tal de-mand (behavioral control) (Maccoby and Martin 1983).

Authoritarian parents are highly controlling in the use of

authority and rely on punishment, but are not responsive.

Authoritative parentsare both demanding and responsive.

Permissive parentsare warm and accepting, but their main

concern is not to interfere with their children’s creativity and independence; these parents are more responsive than de-manding.Uninvolved parentsare low in both responsiveness and demandingness.

Many studies report that poor parental discipline and supervision, as well as hostile parenting, are important risk factors for the development of antisocial behaviors in ado-lescence (Loeber et al.1993; Yoshikawa1994). Studies on child-to-parent violence have identified the following risk factors: difficulties in child-parent relationships, parents with unrealistic expectations, and a lack of adequate com-munication skills (Kennedy et al.2010; Paulson et al.1990; Peek et al.1985).

Gallagher (2008) reported in his review that results about parenting styles differ depending on the type of study. On the one hand, clinical, criminological, health and qualitative studies found that young people are more likely to engage in parent abuse when their parents are overly permissive, and/or apply inconsistent rules and consequences (Cottrell2005; Paulson et al.1990; Robinson et al.2004). On the other hand, quantitative research generally shows that parent abuse occurs when parents are excessively con-trolling or authoritarian (Cottrell and Monk2004; Gallagher 2004; Pagani et al.2004). It has been suggested that in such circumstances parents often apply the same level of rigid control that they applied when their children were younger, causing feelings of humiliation, infantility and re-sentment in adolescents (Straus and Stewart1999). According to Patterson (1980), it is the inconsistent use of punishment, rather than the punishment itself, that contributes to parent abuse.

Although the findings on permissive and authoritarian parenting and their influence on child-to-parent violence may seem paradoxical, both are indeed frequently asso-ciated with adolescents’ delinquent behaviors. Both the authoritarian and permissive styles have been suggested as “ineffective”parenting styles that fail to develop self-control in children (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990) be-cause they: (a) fail to monitor or track the child’s behavior, (b) fail to recognize deviant behavior when it occurs, and (c) fail to correct misconduct. Parents might foster aggressive attitudes either through their own behavior (exerting violence) or by neglecting to do anything about aggressive acts by their children (Unnever et al.2006).

Psychological Profile of Children

According to family systems approach, individual family members and the subsystems that make up the family sys-tem are mutually influenced by and mutually dependent upon one another (von Bertalanffy 1975). This means that not only do parents’characteristics influence the child, but the characteristics of the child may also influence the rela-tionship with parents. Thus, the profile of aggressive ado-lescents and their psychological and social adjustment should also be studied. Many studies describe children who abuse their parents in adolescence as showing lower frustra-tion tolerance and more opposifrustra-tional and aggressive behaviors as well as being more demanding compared to both the general population and to children and adolescents with iden-tified conduct problems (Cottrell and Monk2004; Nock and Kazdin2002). Substance abuse has also been associated with child-to-parent violence (Evans and Warren-Sohlberg 1988; Jackson2003; Pagani et al.2004,2009). Pagani et al. (2009) found significant predictive associations between high levels of substance abuse in both child-to-father physical aggression and verbal aggression, while Pagani et al. (2004) reported that substance abuse among adolescents increased the mother’s likelihood of becoming a victim of verbal aggression by 60 %. Moreover, Walsh and Krienert (2007) found signif-icant sex differences in the relationship between drug abuse and CPV, with sons being significantly more likely than daughters to use drugs or alcohol in cases of both maternal and paternal abuse.

Serious mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders, seem infrequent in adolescents who abuse their parents. However, behavior disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, show special rel-evance (The National Clearinghouse on Family Violence 2003). The results by Kennedy et al. (2010) indicate that juvenile offenders who were violent toward a parent were more psychologically disturbed (more psychiatric hospitaliza-tions, psychotropic medication use or suicide attempts) than those offenders who committed other kinds of offense.

peer group influences the emergence of maladjusted behaviors (Farrington2003).

The current study focuses on child-to-parent violence in a community sample, with a specific emphasis on analyzing gender differences between perpetrators (son vs. daughter) and victims (father vs. mother) in three types of child-to-parent violence (physical, psychological and emotional) in order to shed light on the contradictory results about gender differences from previous studies. One of goals of the present work was to study the relationship between child-to-parent violence and other types of intra-family violence such as inter-parental violence and parent-to-child violence, in order to verify which of these two types of domestic violence is a more relevant risk factor for CPV and to analyze the presence of gender differences in the bi-directionality of violence. Another goal was to identify the psychological profile of perpetrators and the parenting style of their families.

Hypotheses

a) Sons are expected to exert physical violence against their parents more frequently than daughters, while daughters are expected to be more frequently emotionally and verbally abusive towards their parents (Nock and Kazdin2002). b) Mothers are likely to be more frequently the victims of

CPV than fathers (Ibabe and Jaureguizar2010). c) It was hypothesized that a bi-directionality of violence

would be found: it is more likely in families in which parents maltreat their children that there will also be child-to-parent abuse (e.g., Boxer et al. 2009; Ulman and Straus 2003). This bi-directional relationship is expected to be weaker in the case of daughters. d) When physical marital violence is present in the home

there will be a higher probability of finding children who are abusive towards their parents. This relationship between marital violence and child-to-parent violence is expected to be weaker in the case of daughters (Boxer et al.2009).

e) Considering that antisocial behaviors are related to child-to-parent violence (Ibabe et al.in press), it was hypothesized that adolescents who abuse their parents will show personal and social maladjustment.

Methods

Participants

The sample comprised 485 young people of both sexes (55 % sons and 45 % daughters) aged 12 to 18 (X ¼15;SD¼1:69)

from 8 schools (both public and grant-assisted private schools) in the Basque Country (Spain). With regard to violent behaviors, about 21 % of the children in this study had been physically violent to a parent (60 % sons-40 % daughters) and 33 % of them had subjected a parent to psychological abuse (56 % sons and 44 % daughters).

Instruments

Multi-factor Self-Assessment Child Adjustment Test

(TAMAI) (Hernández1998, 3rd. ed.)

The TAMAI is an individually and/or collectively self-applied test for children and adolescents aged 8 to 18. This instrument consists of a 175-itemself-report questionnaire with true-false response format. Its goal is to determine the degree of adjustment at the personal, family, school and social levels, with a view to identifying the roots of malad-justment. It has eight dimensions: personal maladjustment, school maladjustment, social maladjustment, family dissatis-faction, dissatisfaction with siblings, appropriate upbringing by mother, appropriate upbringing by father, and discrepancy of upbringing. Appropriate upbringing is divided into four categories: personalized upbringing (care, affect, respect and control), over-protective (excessive concern and support), per-missiveness (excessive concessions to children’s demands) and restriction/authoritarian style (excessive attitude of control, emotional rejection or abandonment). The alpha reliability coefficient was .87 (Hernández1998).

Drug Abuse

Drug abuse was assessed by a subscale from the Millon

Adolescent Clinical Inventory (MACI) (Millon 2004). The

MACI is designed to assess personality characteristics and clinical syndromes in adolescents. It consists of 160 items grouped into 27 scales which are divided into three main areas: personality characteristics, concerns and clinical syn-dromes. For the current study we used only the 10 items related to drug use (Substance-Abuse Proneness Scale) in-cluded in the clinical syndromes domain. For nine items, participants received one point for each answer as true, since these items were positive (e.g.,“I tried hard drugs to see their effects”). However, the 10th item was negative (e.g.,“Never take drugs, whatever happens”), and in this case the “true” answers were reverse-scored. In this study the alpha reliability coefficient for the scale was .73.

Behavior Assessment System for Children

González et al. 2004) is a multidimensional instrument measuring numerous aspects of behavior and personality including both positive (adaptive) and negative (clinical) dimensions. It is based on statements that must be answered “true” or “false”. The questionnaire for adolescents (aged 12–18) is made up of 14 scales, but only a subset of the psychological scales was used: social stress (level of stress experienced by children in interactions with their peers), sensation-seeking (tendency to take risks, liking for noise and thrill-seeking), anxiety (feelings of nervousness, worry and fear; tendency to feel overwhelmed by problems), esteem (feelings of esteem, respect and self-acceptance) and external locus of control (belief that rewards and punishments are controlled by external events or other people). These rating scales consisted of 62 items. The Spanish adaptation of the test has adequate psychometric properties (see González et al. 2004). Alpha reliability coefficients for the scales used were between .73 and .83.

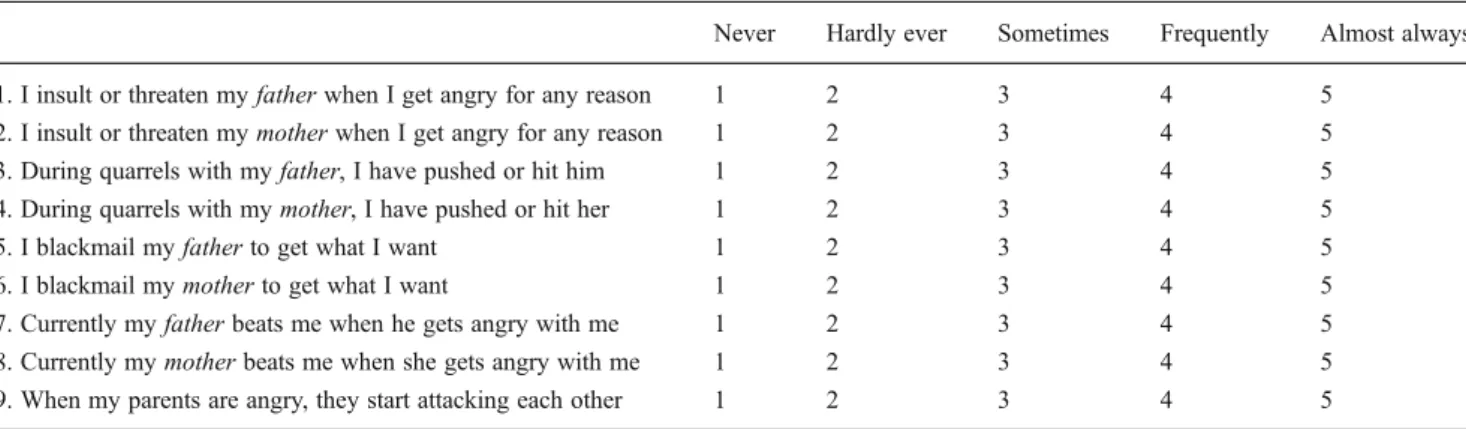

Intra-family Violence ScaleThis questionnaire measures

fam-ily violence: child-to-parent violence and other types of famfam-ily violence (parent-to-child violence and marital violence). This instrument includes nine items with a Likert-type 5-point scale ranging from 1 =Neverto 5 = Almost always, according to the degree of frequency of the violent behavior

(SeeAppendixTable).

Procedure

Once the necessary authorization had been obtained from the relevant institutions, participants were informed of the study goals and of the voluntary nature of their participation. They filled out the protocol at their schools during normal lesson time, collectively, and under the supervision of one of the researchers involved in the study. Data-collection in-structions were standardized and written step-by-step. In each session, participants were informed of the anonymous and confidential nature of the information they provided, and they were never required to identify themselves. The time necessary for application of the protocol varied considerably depending on participants’age (from 60 to 90 min). Once the data had been analyzed, all school staff was offered an infor-mational talk about the factors associated with intra-family violence.

Data Analysis

All data analysis was carried out using SPSS version 17 for Windows, except the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) which was performed using EQS 6.1. Maximum-likelihood exploratory factor analysis was performed for the intra-family violence scale. There were three factors, based on the standard

eigenvalues >1 criterion and they explained 66 % of the total variance. The solution was rotated using Oblimin. The first factor (43 % of total variance) was defined by five items reflecting physical family violence (e.g., “During quarrels with my father/mother, I have pushed or hit him/her”), while the second factor (20 % of total variance) was defined by two items referring to psychological violence against parents (e.g., “I insult or threaten my father when I get angry for any reason”). The third factor (13 % of total variance) corresponded to two items related to emotional violence (e.g., “I blackmail my mother to get what I want). To determine whether it was possible to distinguish clearly between intra-family physical violence and child-to-parent physical vio-lence, items for the first factor were entered in a specified two-factor solution. The first factor was defined by items related to the CPV, while the second factor was related to items on violence from parents to children. However, the item related to marital violence was not associated with either of the two factors. Reliability analysis and confirmatory factor analysis were made for this scale.

We examined child-to-parent violence depending on child’s gender (son vs. daughter), type of violence (physical, psychological and emotional), and parent’s gender (father vs. mother) using a 2×(3×2) mixed model ANOVA. The dependent variables were measured by the frequency of violent behaviors against their parents as reported by the children. The Greenhouse-Geisser correction of degrees of freedom was applied where necessary, and an a posteriori Bonferroni correction for post-hoc analysis was applied because it is a mixed design ANOVA.

Next, we analyzed violent behavior in the family in the present situation, focusing on physical violence. To examine the bi-directionality of violence in child-to-parent violence, a 2×2×2 ANOVA was used, with Parent-to-Child Violence (yes/no), Marital Violence (yes/no) and Child’s Gender (son vs. daughter) as between-group factors, in order to exam-ine the relative strength of the two variables of family violence (parent-to-child physical violence and marital violence) in the physical child-to-parent violence depending on child’s gender. The dependent variable was measured by the frequency of physical violence against their parents as reported by the children. Tukey post-hoc analysis was applied to comparisons of interaction analysis

by mother and social maladjustment as predictor variables. Also it was checked whether the model obtained was valid for both sons and daughters.

Results

Reliability and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The results indicated that alpha reliability coefficients for the child-to-parent violence scale (alpha = .80) and intra-family violence scale (alpha = .79) were adequate. Subsequently, we applied a confirmatory factor analysis containing a second-order latent factor comprising the CPV (physical, psychological and emotional) and a first-order latent factor referring to intra-family violence. The CFA model presented an adequate fit to the data with the robust method (standardized kurtosis coeffi-cient, Yuan et al.2004= 180.91, Y Bχ2 (20, N= 485) = 47.1,

CFI=.95,NNFI=. 91,IFI=.95,RMSEA=.054). In addition, the results indicated that the CPV scale (alpha = .80) and the family violence scale (alpha = .79) had adequate reliability. According to Nunnally’s (1978) criteria, alpha≥.70 signifies adequate reliability in the psychology field.

Type of Child-to-Parent Violence and Gender Differences

There were two significant main effects: Type of Violence F(1.97, 798.2)=44.75,p<.001,η2=.09, and Parent’s Gender, F(1, 434)=13.84,p<.001,η2=.03. According toa posteriori Bonferroni correction, the rate of physical violence (M=1.38) was lower than those for psychological (M=1.59) (p<.001) and emotional violence (M=1.93) (p<.001). Furthermore, adolescents behaved more violently toward their mother (M= 1.67) than toward their father (M=1.59).

Type of Violence interacted significantly with Child’s Gender, F(1.97, 798.2) = 5.05, p= .007, η2= .11, and also with Parent’s Gender,F(1.84, 798)=6.72,p=.001,η2=.01. According to Fig.1, the results of the Type of Violence × Child’s Gender interaction indicate that sons directed more physical violence towards their parents than daughters (p= .03), while there were no significant differences for psychological and emotional violence.

Additionally, in the second interaction analysis adolescents were found to be more psychologically violent (p=.001) and emotionally violent (p=.001) towards mothers than towards fathers, but such differences were not found for physical violence (see Fig.2).

Bi-Directionality of Violence in Child-to-Parent Violence

There were three significant main effects: Parent-to-Child ViolenceF(1, 427)=6.54,p=.01,η2=.01, Marital Violence, F(1, 427) =24.35, p=.000, η2=.05, and Child’s Gender,

F(1, 427) = 22.76, p< .001, η2= .05. Adolescents that suf-fered physical abuse from the parent showed more violent behaviors toward the parent (M= 4.09) than those who did not experience physical abuse (M= 2.54).

Parent-to-Child Violence and Marital Violence interacted significantly with Child’s Gender, [F(1, 427)=3.97,p=.047,

η2

=.02, andF(1, 427)=20.00,p<.001,η2=.04, respectively] (See Figs.3and4). According to Tukey post-hoc comparisons of the first interaction, when adolescents suffered abuse by their parents, sons presented significantly higher levels of violence than daughters (p<.001). However, there were no significant differences between sons’and daughters’violence when they had not been abused by their parents.

According to the main effect of marital violence, adoles-cents who observed marital violence at home showed more physical child-to-parent violence (M=4.87) than those who

1 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2 2.2

Physical Psychological Emotional

Estimated M

a

rginal

M

e

ans

Type of violence Child's Gender

Son

Daughter

Fig. 1 Interaction between type of violence and child’s gender

1 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2 2.2

Physical Psychological Emotional

Estimated M

a

rginal

M

e

ans

Type of violence Parent's Gender

Father

Mother

did not witness marital violence at home (M= 2.53). As shown in Fig. 4, Tukey post-hoc analysis of the second interaction revealed that sons and daughters showed the same level of violence against their parents when marital violence was not present at home. When they did witness marital violence at home, sons presented much higher levels of violence against their parents than daughters (p<.001).

Parenting Style and Psychological Profile of Adolescents

Appendix Table shows the correlations between violence

towards parents, parenting style and psychological profile of children. Child-to-parent physical abuse was linked to inappropriate upbringing by the mother (r=−.17, p=.002), emotional rejection by the mother (r= .16, p= .001) and some psychological variables of adolescents, such as low self-esteem (r=−.21, p= .001), external locus of control (r=.13,p=.008), social maladjustment (r=.21,p<.001) and drug abuse (r=.22, p<.001). Moreover, psychological and

emotional violence against parents were linked to these psy-chological variables. It should also be noted that child-to-parent emotional abuse was correlated with permissive par-enting style (by the father r= .15, p= .002; by the mother r= .11, p= .02), authoritarian style by the mother (r= .10, p=.04), and emotional rejection by the mother (r=.16,p=.001). Multiple regression analyses were carried out to examine some variables as predictors of child-to-parent physical violence. The best predictors of physical violence against parents were drug abuse (β=.23, p< .001), inappropriate upbringing by mother (β=−.15, p= .006) and social mal-adjustment (β= .14, p= .009), R2= .10, F(3, 317) = 12.63, p<.001. Gender differences were also found in the profile of children who battered their parents. For sons, the model explained 20 % of variance in child-to-parent physical vio-lence, and inappropriate upbringing by mother (β=−.28, p< .001), social maladjustment (β=.25, p<.001) and drug abuse (β=.18,p=.009) were significant predictors,R2=.20, F(3, 169)=15.78, p<.001. However, among daughters this model explained only 7 % of variance in child-to-father vio-lence,R2=.07,F(3, 144)=4.64,p=.01, and only drug abuse was statistically significant (β=.25,p=.003). The characteris-tics of sons who batter their parents are different from those of daughters, and the variables studied were found to predict the violent behavior of sons much better.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to analyze gender differ-ences between perpetrators (son vs. daughter) and victims (father vs. mother) in three types of child-to-parent violence (physical, psychological and emotional). The difference be-tween psychological and emotional abuse is supported theo-retically by numerous scientific articles (e.g., Cottrell 2001; Edenborough et al. 2008; Haw 2010; Howard and Rottem 2009; Kennair and Mellor2007) and empirically by the results of the exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis previously presented. Two significant interactions emerged: gender of perpetrator × type of violence, and gender of victim × type of violence. Furthermore, relations between different types of intra-family violence (child-to-parent violence, inter-parental violence and parent-to-child violence) were found, and the results revealed gender differences in the bi-directionality of family violence. Finally, we identified family risk factors (inappropriate upbringing by mother and marital violence) and adolescents’personal risk factors (drug abuse and social maladjustment) that predict child-to-parent physical violence.

Perpetrators and Victims

As expected, sons were found to use more physical violence against their parents than daughters, although the difference

2 2.5 3 3.5 4 4.5 5 5.5 6

No Yes

Estimated M

a

rginal

M

e

ans

Child-to-Parent Violence Child's Gender

Son

Daughter

Fig. 3 Interaction between child’s gender and parent-to-child violence

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

No Yes

Estimated M

arginal M

eans

Marital Violence Child's Gender

Son

Daughter

was very small. Traditionally, it has been thought that males are more aggressive than females in both domestic violence and community-based gang aggression, and research has backed this up (Archer2004; Paulson et al. 1990). Congruent with such findings, Ulman and Straus (2003) found that in four out of five studies on child-to-parent violence, more boys than girls hit parents. In line with our own results, Gallagher (2008) suggests in his review that the trend seems to be toward fewer differences between girls and boys as the severity of parent abuse decreases. In that review, studies using survey data (with community samples and with high-risk adolescents) failed to find any statistically significant differences in gender of aggressor, while in other types of studies (clinical, judicial and qualitative) boys were found to be perpetrators of child-to-parent violence by about three to one in comparison to girls. Consistent with this conclusion, Walsh and Krienert (2007), using a large cross-national sample of reported offenders (n=17,957), found that sons were the predominant offenders in child-to-parent violence. In aggravated assault, simple as-sault, or intimidation, sons were consistently the largest cate-gory of child-to-parent violence offenders. In regards to psychological and emotional abuse, although we hypothe-sized that this would be more common among daughters, no differences were found.

It was also hypothesized that mothers would be victims of parent abuse more frequently than fathers. This hypoth-esis was partially confirmed, since there was an interaction between parent’s gender and type of violence. As far as physical violence is concerned, no differences were found, though mothers suffered more psychological and emotional violence than fathers regardless of the child’s gender. Our result is in line with Gallagher’s (2008) conclusion, since he found that in community samples based on adolescents’and parents’self-reports there were only small differences in victimization of fathers and mothers.

It is also possible that the most serious crimes are committed against mothers, so that in judicial or clinical samples the number of mothers who are the victims is much higher. In any case, it is not easy to explain why mothers were usually the victims of their children’s violence in a legal sample from the Basque Country (Spain) (Ibabe et al.2009; Ibabe and Jaureguizar2010), while in a community sample from the same region the rates of physical violence against fathers and mothers were similar. In the former study, using the legal sample (court reports), Ibabe et al. (2009) found that 80 % of the victims were mothers abused by their sons. In the present study, children were the survey respondents, and it may be that they failed to report violence towards mothers ac-curately since assaulting mothers is largely considered unacceptable in our society. In general, indeed, there is

a clear cultural norm that defines hitting parents as particu-larly discreditable behavior (Ulman and Straus2003). It is, of course, also possible that when fathers are victims of their children’s violence they are reluctant to turn to the judicial system to solve their family conflict because of feelings of guilt and shame.

Bi-Directionality of Family Violence

In this study the hypothesis of the bi-directionality of vio-lence was verified: adolescents in families where both inter-parental and parent-to-child physical violence were present were the most likely to engage in CPV. This finding is consistent with Pagani et al.’s (2009) research with a community sample in which they reported that a child-hood behavioral pattern characterized by physical ag-gression showed the highest risk of verbal agag-gression and physical aggression toward fathers, regardless of sex. This result is consistent with recent research using clinic-referred samples (Boxer et al. 2009) or judicial samples (Kennedy et al.2010).

According to our hypothesis, the bi-directionality of family violence was much higher in sons than in daugh-ters. These results are also consistent with Stith et al.’s (2000) meta-analysis on the intergenerational transmis-sion of spouse abuse. The findings of that meta-analysis suggest that both experiencing child abuse and witnessing interparental violence are more strongly associated with sub-sequently becoming a perpetrator of partner violence for men than for women.

Family and Children’s Profile

In the present study some parenting styles or parenting practices by the mother were associated with child-to-parent physical violence, but the intensity of that relationship was not high. Appropriate upbringing by mothers was a protective factor for physical violence against parents, while emotional rejection by mother was a risk factor. It is well known that young people are more likely to engage in parent abuse when their parents are overly permissive, display in-consistent rules (e.g., Paulson et al.1990) or are excessively controlling (Cottrell and Monk2004). However, in this study permissive and authoritarian parental styles were only related to emotional CPV not to physical and psychological abuse. It may be that family discipline method is not as relevant as the showing of clear signs of affection and acceptance (Hernández et al.2008).

Previous studies have shown that abused or neglected children with attachment problems could be violent to carers (Briggs and Broadhurst2005; Stanley and Goddard2002). It is possible that a weak parent-child involvement through shared activities and positive communication is a risk factor for verbal aggression from sons and daughters. Pagani et al. (2009) noted that being a college-educated father was associated with a 40 % greater chance of experiencing verbal aggression from children. However, there was no such link between maternal education and aggression toward mothers. College-educated fathers are more likely to have jobs with more responsibility and consequently weaker relationships with children; parents in such families may have less room to maneuver in the family conflict context.

Regarding the profile of adolescents who battered their parents, drug abuse, self-esteem, external locus of control

and social maladjustment were moderately associated with physical, psychological and emotional CPV. Previous stud-ies have linked the abuse of alcohol or drugs to child-to-parent abuse (Jackson2003; Pagani et al.2004,2009). Pagani et al. (2009) reported that problematic substance use by sons dou-bled the risk of child-to-father physical aggression. It seems that high levels of substance use make sons both verbally and physically uninhibited about confronting their fathers. In ad-dition, we found gender differences in risk factors for CPV, since inappropriate upbringing and social maladjustment were risk factors for boys but not for girls.

In sum, although most studies on this phenomenon are in agreement that mothers are far more often the victims of abuse from their young children, in this study with a community sample there were only small differ-ences in the victimization of fathers and mothers. The bi-directionality was much higher in boys than in girls, possibly as a result of cultural socialization practices and modeling influences of same-sex parent behavior (Boxer et al.2009; Stith et al.2000).

Finally, a limitation of the present research is that the data was obtained exclusively from adolescent self-reports. Future research should also obtain information from other family members for a fuller and more accurate perspective on the family. However, it should be noted that some re-search on adolescence stresses the importance of the ado-lescent’s subjective experience, arguing that the way in which children perceive their parents’ behavior is of more influence on their development than is parents’actual be-havior (Steinberg et al.1992). In any case, further research is needed to analyze the psychological and psychopatholog-ical profile of adolescents who behave violently toward their parents with different types of samples (community, clinical and judicial).

Appendix

Table 1 Intra-family violence scale

Never Hardly ever Sometimes Frequently Almost always

1. I insult or threaten myfatherwhen I get angry for any reason 1 2 3 4 5 2. I insult or threaten mymotherwhen I get angry for any reason 1 2 3 4 5 3. During quarrels with myfather, I have pushed or hit him 1 2 3 4 5 4. During quarrels with mymother, I have pushed or hit her 1 2 3 4 5

5. I blackmail myfatherto get what I want 1 2 3 4 5

6. I blackmail mymotherto get what I want 1 2 3 4 5

References

Agnew, R., & Huguley, S. (1989). Adolescent violence toward parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 5(3), 699–711.

Archer, J. (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: a meta-analytic review.Review of General Psychology, 8(4), 291–322. Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence, 11(1), 56–95.

Boxer, P., Gullan, R. L., & Mahoney, A. (2009). Adolescents’physical aggression towards parents in a clinically referred sample.Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38(1), 106–116. Briggs, F., & Broadhurst, D. (2005). The abuse of foster carers in

Australia.Journal of the Home Economics Institute of Australia, 12(1), 25–35.

Cornell, C. P., & Gelles, R. J. (1982). Adolescent-to-parent violence. Urban Social Change Review, 15(1), 8–14.

Cottrell, B. (2001).Parent abuse: The abuse of parents by their teenage children. Canada: The Family Violence Prevention Unit Health. Cottrell, B. (2005).When teens abuse their parents. Halifax: Fernwood

Publishing.

Cottrell, B., & Monk, P. (2004). Adolescent-to-parent abuse. A qual-itative overview of common themes. Journal of Family Issues, 25(8), 1072–1095.

Crawford-Brown, C. (1999). The impact of parenting on conduct disorder in Jamaican male adolescents.Adolescence, 34(134), 417–436. Downey, L. (1997). Adolescent violence: a systemic and feminist

perspective. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 18(2), 70–79.

Edenborough, M., Jackson, D., Mannix, J., & Wilkes, L. M. (2008). Living in the red zone: the experience of child-to-mother vio-lence.Child and Family Social Work, 13(4), 464–473.

Evans, E. D., & Warren-Sohlberg, L. (1988). A pattern of analysis of adolescent abusive behaviour towards parents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 3(2), 201–216.

Farrington, D. P. (2003). Advancing knowledge about the early pre-vention of adult antisocial behaviour. In D. P. Farrington & J. W. Coid (Eds.),Early prevention of antisocial behaviour(pp. 1–31). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Farrington, D. P., & West, D. J. (1993). Criminal, penal and life histories of chronic offenders: risk and protective factors and early identifi-cation.Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 3(4), 492–523. Gallagher, E. (2004). Youth who victimise their parents.Australian

and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 25(2), 94–105. Gallagher, E. (2008). Children’s violence to parents: A critical

literature review. Master thesis. Melbourne, Australia: Monash University. Retrieved April 18, 2012 from, http://web. aanet.com.au/eddiegallagher/Violence%20to%20Parents%20-%20Gallagher%202008.pdf.

Gelles, R. J., & Straus, M. A. (1988).Intimate violence. New York: Simon and Schuster.

González, J., Fernández, S., Pérez, E., & Santamaría, P. (2004). Adaptación española del Sistema de Evaluación de la Conducta en Niños y Adolescentes: BASC [Spanish adaptation of the Behavior Assessment System for Children and Adolescents]. Madrid: TEA Ediciones.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990).A general theory of crime. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Granic, I., & Patterson, G. R. (2006). Toward a comprehensive model of antisocial development: a dynamic systems approach. Psychological Review, 113(1), 101–131.

Haw, A. (2010).Parenting over violence. Government of Western Australia. Department for Communities. Retrieved October 1, 2012 from http://patgilescentre.org.au/about-pgc/reports/parent-ing-over-violence-final-report.pdf.

Hernández, P. (1998).Test Autoevaluativo Multifactorial de Adaptación Infantil (TAMAI), [Multi-factor Self-Assessment Child Adjustment Test (TAMAI)]. Madrid: TEA Ediciones.

Hernández, M., Gómez, I., Martín, M. J., & González, C. (2008). Prevención de la violencia infantil- juvenil: estilos educativos de las familias como factores de protección [Prevention of child and adoles-cents’violence: Parenting styles as protection factors].International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 8(1), 73–84. Howard, J. (1995). Family violence: children hit out at parents.

Community Quarterly, 34, 38–43.

Howard, J., & Rottem, N. (2009).It all starts at home. Male adolescent violence to mothers. Inner South Community Health Service Inc and Child Abuse Research Australia, Monash University. Ibabe, I., & Jaureguizar, J. (2010). Child-to-parent violence: profile of

abusive adolescents and their families. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(4), 616–624.

Ibabe, I., Jaureguizar, J., & Díaz, O. (2009). Adolescent violence against parents: is it a consequence of gender inequality?The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 1(1), 1–13. Ibabe, I., Jaureguizar, J., & Bentler P. M. (in press) Protective factors for

adolescents violence against authority.Spanish Journal of Psychology. Jackson, D. (2003). Broadening constructions of family violence: mothers’ perspectives of aggression from their children. Child and Family Social Work, 8(4), 321–329.

Kennair, N., & Mellor, D. (2007). Parent abuse: a review. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 38(3), 203–219.

Kennedy, T. D., Edmonds, W. A., Dann, K. T. J., & Burnett, K. F. (2010). The clinical and adaptive features of young offenders of child-parent violence.Journal of Family Violence, 25(5), 509–520.

Kethineni, S. (2004). Youth-on-parent violence in a central Illinois county.Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2(4), 374–394. Kratcoski, P. C., & Kratcoski, L. D. (1982). The relationship of

victimization through child abuse to aggressive delinquent behav-iour.Victimology: An International Journal, 7(1–4), 199–203. Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., & Neidig, P. (1995). Violent backgrounds

of economically disadvantaged youth: risk factors for perpetrating violence?Journal of Family Violence, 10(4), 379–397.

Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Neidig, P., & Thorn, G. (1995). Violent marriages: gender differences in levels of current violence and past abuse.Journal of Family Violence, 10(2), 159–176. Loeber, R., Wylie-Weiher, A., & Smith, C. (1993). The relationship

between family interaction and delinquency and substance use. In D. Huizinga, R. Loeber, & T. P. Thornberry (Eds.),Crime and justice: An annual review of research(Vol. 7, pp. 29–149). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In P. H. Mussen & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.),Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development(4th ed., pp. 1–101). New York: Wiley. Mahoney, A., & Donnelly, W. O. (2000, June). Adolescent-to-parent

physical aggression in linic-referred families: Prevalence and co-occurrence with parent-to-adolescent physical aggression. Paper presented in Victimization of Children and Youth: An International research Conference, University of New Hampshire. Durham, NH. Maxwell, C. D., & Maxwell, S. R. (2003). Experiencing and witnessing familiar aggression and their relationship to physically aggressive behaviours among Filipino adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(2), 1432–1451.

McCloskey, L. A., & Lichter, E. (2003). The contribution of marital violence to adolescent aggression across different relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(4), 390–412.

Millon, T. (2004).MACI. Inventario Clínico para Adolescente [MACI. Adolescent Clinical Inventory]. Madrid: TEA Ediciones. Nock, M. K., & Kazdin, A. E. (2002). Parent-directed physical

Nunnally, J. C. (1978).Psychometric theory(2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pagani, L. S., Larocque, D., Vitaro, F., & Tremblay, R. E. (2003). Verbal and physical abuse toward mothers: the role of family configuration, environment, and doping strategies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(3), 215–223.

Pagani, L. S., Tremblay, R. E., Nagin, D., Zoccolillo, M., Vitaro, M., & McDuff, P. (2004). Risk factor models for adolescent verbal and physical aggression toward mothers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(6), 528–537.

Pagani, L. S., Tremblay, R. E., Nagin, D., Zoccolillo, M., Vitaro, F., & McDuff, P. (2009). Risk factor models for adolescent verbal and physical aggression toward fathers.Journal of Family Violence, 24(3), 173–182.

Patterson, G. R. (1980). Mothers: the unacknowledged victims. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 45(59), 1–49.

Patterson, G. R. (1982).Coercive family process. Eugene: Castalia. Patterson, G. R. (1986). Performance models for antisocial boys.

American Psychologist, 41(4), 432–444.

Patterson, G. R., Dishion, T. J., & Bank, L. (1984). Family interaction: a process model of deviancy training.Aggressive Behavior, 10(3), 253–267.

Paulson, M. J., Coombs, R. H., & Landsverk, J. (1990). Youth who physically assault their parents.Journal of Family Violence, 5(2), 121–133.

Peek, C. W., Fischer, J. L., & Kidwell, J. S. (1985). Teenage violence toward parents: a neglected dimension of family violence.Journal of Marriage and the Family, 47(4), 1051–1058.

Reynolds, C., & Kamphaus, R. W. (1992).Behavior assessment system for children-BASC. Circle Pines: American Guidance Service. Robinson, P. W., Davidson, L. J., & Drebot, M. E. (2004). Parent abuse

on the rise: A historical review.American Association of Behavioral Social Science Online, 58–67. Retrieved April 18, 2012 from,http:// aabss.org/Perspectives2004/AABSS_58–67.pdf.

Stanley, J., & Goddard, C. (2002). In the firing line: violence and power in child protection work. Chichester: Wiley.

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Dornbusch, S. M., & Darling, N. (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed.Child Development, 63(5), 1266–1281.

Stewart, M., Jackson, D., Mannix, J., Wilkes, L., & Lines, K. (2005). Current state of knowledge on child-to-mother violence: a litera-ture review.Contemporary Nurse, 18(1–2), 199–210.

Stith, S. M., Rosen, K. H., Middleton, K. A., Busch, A. L., Lundeberg, K., & Carlton, R. P. (2000). The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: a meta-analysis.Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62(3), 640–654.

Straus, M. A., & Hotaling, G. T. (1980).The social cause of husband-wife violence. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Straus, M. A., & Stewart, J. H. (1999). Corporal punishment by

American parents: national data on prevalence, chronicity, sever-ity and duration, in relation to child and family characteristics. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2(2), 55–70. The National Clearinghouse on Family Violence (2003).Parent abuse:

The abuse of parents by their teenage children. Canada: Canada Government. Retrieved October 1, 2012 from, http://www. phac-aspc.gc.ca/ncfv-cnivf/pdfs/Abuse_E.pdf.

Ulman, A., & Straus, M. A. (2003). Violence by children against mothers in relation to violence between parents and corporal punishment by parents.Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 34, 41–60. Unnever, J. D., Cullen, F. T., & Agnew, R. (2006). Why is “bad”

parenting criminogenic? Implications from rival theories.Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 4(1), 3–33.

von Bertalanffy, L. (1975). General system theory and psychiatry. In S. Arieti (Ed.),American handbook of psychiatry, Vol I(2nd ed., pp. 1095–1117). New York: Basic Books.

Walsh, J. A., & Krienert, J. L. (2007). Child-parent violence: an empirical analysis of offender, victim, and event characteristics in a national sample of reported incidents.Journal of Family Violence, 22(7), 563–574.

Walsh, J. A., & Krienert, J. L. (2009). A decade of child-initiated family violence: comparative analysis of child parent violence and parricide examining offender, victim and event characteristics in a National Sample of Reported Incidents, 1995–2005.Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(9), 1450–1477.

Yoshikawa, H. (1994). Prevention as cumulative protection: effects of early family support and education on chronic delinquency and its risks.Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 28–54.