Use of English lexical borrowings in Sonoran border Spanish

Texto completo

(2) USE OF ENGLISH LEXICAL BORROWINGS IN SONORAN BORDER SPANISH. Thesis presented. By JAY PAUL PENCE DUDGEON. Presented far the Virtual University of the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey in partial fulfillrnent far the degree of. MASTER IN EDUCATION WITH A SPECIALIZATION IN APPLIED LINGUISTICS (ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE TEACHING) ..,'. '. May, 2000.

(3) INSTITUTO TECNOLOGICO Y DE ESTUDIOS SUPEIUORES DE MONTERREY UNIVERSIDAD VIRTUAL CAMPUS SONORA NORTE ') ,}r: 1¡ ... ,. ACTA DE EXAMEN Y AUTORIZACION DE LA EXPEDICION DE GRADO ACADEMICO. Los suscritos, miembros del jurado calificador del examen de grado sustentado hoy por JAY PAUL KERMIT PENCE DUDGEON en opción al grado académico de MAESTRO EN EDUCACION, ESPECIALIDAD EN LINGUISTICA (INGLES). hacemos constar que el sustentante resultó. m._ ~=. rr¿j~@ .. MTRA .MARIA TERESA Mlli. ;. CERVANTES. o. r,o 'ba.do. -\)Oí U Y'lct. ni ~ d . ,. /~~ DRA. CLAUD;,;;;,.,sm!o~. Hago constar que el sustentante, de acuerdo con documentos contenidos en su expediente, ha cumplido con los requisitos de graduación, establecidos en el Reglamento Académico de lo~ogramas de graduados. Universidad Virtual.. ING. LUIS. Director de Servicios Escolares. Expida.se el grado académico mencionado, con fecha 23 DE Ml\YO DE. ING. CARLOS CRUZ LIMON. Rector de la Universidad Virtual. Hermosillo, Sonora,. e. 03 DE MAYO DE 2000..

(4) ABSTRACT. USE OF ENGLISH LEXICAL BORROWINGS IN SONORAN BORDER SPANISH MAY, 2000 JAY P. PENCE BACHELOR OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA MASTER OF THEOLOGICAL STUDIES HARVARD UNIVERSITY MASTER OF EDUCATION INSTITUTO TECNOLÓGICO Y DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES DE MONTERREY Directed by Professor Fabiola Ponce Ehlers-Zavala, Ph.D.. This study examined the use of English lexical borrowings, or anglicisms, in the everyday speech of border region residents in Sonora, Mexico. A written questionnaire was applied to 287 public high school students from four cities at varying distances from the U.S.-Mexican border. These cities were Agua Prieta, Magdalena, Caborca, and Navajoa. The purpose of the study was to establish density of anglicisms in border Spanish for sociolinguistic purposes related to language education. The questionnaire asked participants to selector provide synonyms for 50 standard Spanish lexical items. lt was hypothesized that a high percentage of subjects would selector provide English lexemes as synonyms rather than standard Spanish synonyms. Moreover, it was hypothesized that the percentage of anglicisms selected by subjects would be related to their proximity to the border. The findings show that the use of anglicisms in the speech of high school students in the border region of Sonora is measurably significant. Using a multi-choice. ¡¡.

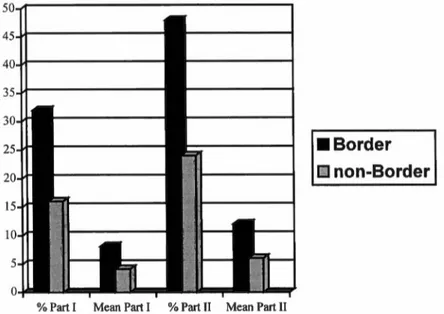

(5) method, border region participants selected anglicisms as synonyms 32% of the time, while non-border participants selected anglicisms only 16%. Using a method asking participants to provide their own synonyms, border region speakers responded with anglicisms 48% of the time, while non-border region speakers 24%. The results indicate neither fonnal English classes, time spent in the United States, nor use of computer and internet are measurable extra-linguistic characteristics of Sonaran speakers. However, a small but significant difference was demonstrated between cable television viewing and prívate English lessons and use of anglicisms, when comparing border and non-border speakers. This study concludes that the high density of anglicisms in the speech of border region Sonaran high school students warrants special consideration of these speakers in second language instruction. Moreover, the use of anglicisms is related to the factor of geography more than any other non-linguistic variable. Thus, a proposal for English as a Second Language (ESL) vocabulary instruction that accounts for these border culture Spanish speakers and their linguistic variety is provided for border culture classrooms.. 111.

(6) CONTENTINDEX. Chapter. Page. ABSTRACT ..................................................................... ii CONTENT INDEX ............................................................ iv TABLE INDEX ................................................................. vii FIGURE INDEX ............................................................... viii INTRODUCTION.................. . ........................................... 1 1.1 Theme .......................................................... 2 1.2 Background ................................................... 3 1.3 Problem ....................................................... 4 1.4 Hypothesis .................................................... 6 1.5 Relevance ..................................................... 6 1.6 Outline ......................................................... 7 2. BACKGROUND ANO THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS: SOCIOLINGUISTICS .............................. 9 2.1. Introduction to Sociolinguistics ............................ 9 2.1.1. Sociolinguisitcs and Spanish ................. 12 2.2. Dialectology ................................................. 14 2.3. Lexical Dialectological Studies .......................... 16 2.4. Review of Lexical Dialectology ......................... 18 2.5. Lexical Studies of English Borrowings in Spanish .... 22 2.6. Summary .................................................... 27. iv.

(7) 3. BACKGROUND ANO THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS: ENGLISH AS A SECOND LANGUAGE ...... 28 3.1. The Universalization ofEnglish, Language Planning and Education ................................... 28 3.2. English as a Second Language (ESL) Theory .......... 36 3.3. ESL Vocabulary Instruction Theory ................... .44 3.4. Summary ................................................... 45. 4. METHODS ..................................................................... 46 4.1. Design ........................................................ 46 4.2. Participants ................................................. .48 4.3. Materials .................................................... 50 4.3.1.. The Questionnaire ........................... 51. 4.3.2.. The Lexical Items ........................... 52. 4.3.3.. Extra-linguistic Variables ................. 54. 4.4. Procedures ................................................. 55 5. RESULTS ...................................................................... 57 5.1. Statistical Analysis ....................................... 57 5.2. Overall Sample Statistics ................................ 58 5.2.1.. Overall Results from Part J.. .............. 58. 5.2.2.. Overall Results from Part II ............... 60. 5.2.3.. Results for each City ....................... 62. 5.2.4.. Summary of Overall Results .............. 63. 5.3. Border and non-Border City Comparison ............. 64 5.4. Demographic Results .................................... 69 5.5. Summary .................................................... 74 6. DISCUSSION ANO CONCLUSIONS .................................... 75 6.1. Discussion ................................................. 75. V.

(8) 6.1.1. Discussion of Sample ...................... 76 6.1.2. Discussion of Methodology ............... 76 6.1.3. Discussion of Extra-linguistic Variables .................................... 76 6.1.4. Discussion of Theoretical lmplications ................................. 81 6.2. Conclusions ............................................. 85 7. IMPLICATIONS FOR ESL EDUCATION AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH ....................... 89 7 .1. Implications of Results ................................ 89 7.2. Didactic Techniques for the ESL Classroom in Sonora ................................................ 89 7.3. Suggestions for Further Research .................... 96 REFERENCES .............................................................. 98 APPENDICES .............................................................. 107 Appendix A ................................................ 108 Appendix B ................................................ 118 Appendix C ................................................ 131 Appendix D ................................................ 144 VITAE. vi.

(9) TABLES INDEX. Table. Page. Number and Gender of Participants by City ......................... 50 2. English Synonym Selection for Part l.. ............................... 59. 3. Negative Responses and Spanish Responses ........................ 60. 4. English Synonym Selection for Part II. .............................. 61. 5. No Responses and Spanish Responses for Part II .................. 62. 6. Percent of English Synonyms: Agua Prieta v. Navajoa ........ 65-66. 7. Inferential Statistics of Significance for Part I ...................... 67. 8. lnferential Statistics of Significance for Part 11 ..................... 68. 9. Demographic Categories ............................................... 69. 10. Use ofTechnology: Overall. .......................................... 70. 11. Use of Technology: Border City v. non-Border City .............. 71. 12. Direct Exposure to English: Overall ................................. 72. 13. Direct Exposure to English: Border City v. non-Border City ..... 73. 14. Evaluation of Questionnaire: Overall ................................ 73. 15. Evaluation of Questionnaire: Border City v. non-Border City ... 74. 16. Total Number of Anglicisms by Method ........................... 77. VII.

(10) FIGURES INDEX. Figure. Page. The State of Sonora .................................................... 49 2. Selection of Anglicisms by City: 5 Cases .......................... 63. 3. Frequency of English Selection for 10 Lexical Items ............ 64. 4. Summary of Results: Border v. non-Border ........................ 68. 5. Cable T.V. Use by City ............................................... 80. 6. Socio-linguistic Border Zone of Sonora ............................ 87. viii.

(11) CHAPTERI. Introduction. 1. The rapid spread of American culture and the English language throughout the world have become controversia) issues, especially with the advent oftechnology and the conclusion of the cold war. One only needs to look at today's periodicals and news journals to identify the perceived advantages and fears of a universal set of values and mode of communication. Less newsworthy, but perhaps more important, is the study of inter-cultural influences, and the mutual effects of cultures and languages in everincreasing contact. As the planet becomes increasingly smaller, such studies will prove essential for the further beneficia) development of civilization. The study of languages in contact plays a significant role in understanding cultures, values, and human development. Although the scientific field of how society and languages relate, called sociolinguistics, is relatively new and often misunderstood, understanding how languages change can help us to understand how people change. Sociolinguistics recognizes factors such as ethnicity, age, gender, and geographic area in the attempt to understand language use and change (Hudson, 1980; Trudgill, 1974). One of the principie tenants of sociolinguistics is: language and society are so closely related that one cannot communicate anything through language without revealing something about ones self (Trudgill, 197 4 ). English and Spanish are two of the world · s most heavily used languages. The study of how they interact and change each other and their respective speakers, especially considering the traditional differences between Anglo and Latin cultures, emerges as an important scientific and humanistic endeavor. The purpose of the following study is to contribute a small amount to this endeavor.. 1.

(12) Theme 1.1. The focus of this investigation is the use of English vocabulary in the daily spoken Spanish of Mexicans living along the Arizona-Sonora border. The use ofwords from another language, called lexical borrowing, is a common linguistic occurrence for all languages (Hudson, 1980). For example, a native English speaker might use the word. patio, a term borrowed from Spanish to designate an area outside the house. However, there is a distinction between a lexical item that has become an accepted and permanent part of the standard language, and a lexical item that has been borrowed only recently or by a specific group of speakers. This distinction provokes many questions about the proper use of the borrowing language, and the values and education of its speakers. Although there are relatively few studies (e.g., Galindo, 1996; Bustamante, 1982) which address the theme of border Spanish in Mexico, border speakers are clearly aware of the differences between the Spanish they speak and the Spanish spoken in other parts of Mexico and Latin America. For example, in Sonora I have heard individuals speak of country speech, coastal speech, southern speech, and border speech as distinct dialects of Spanish. The explicit theme ofthe present study, then, is the product of the following questions: 1.. Do Mexicans from the border region speak a variety of Spanish that includes a high quantity of borrowed English lexical items?. 2.. Do border region speakers use more English lexical items than non-border region speakers?. 3.. What are the implications for education and language instruction for speakers of border Spanish?. 2.

(13) Background 1.2. The preceding research questions evolved from my English as a Second Language (ESL) teaching experience at the Instituto Tecnologico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey (ITESM) campus in Hermosillo, Sonora from 1992 until the present. 1t is the culmination of a very basic reality in my classrooms: students from towns nearer the border have a broader English vocabulary than other students not from the border region, regardless of amounts of formal English education. Nevertheless, though students closer to the border tend to have a greater vocabulary and understand English better, their usage is often erroneous or awkward in terms of accepted standard English. In addition, because these border region students know more English vocabulary, they tend to become easily bored by classroom instruction that fails to account for their unique linguistic awareness of English. Thus, I began to wonder whether ESL instruction, or at least vocabulary instruction, for students from border areas ought to be altered or specialized in accordance with their apparent informal knowledge of English. The theme of border Spanish is not new. There are a number of interesting linguistic, sociolinguistic, educational, and sociological studies that have been conducted in recent years about Mexican-American speakers of Spanish living in the United States ( e.g., Gal indo, 1996; Penal osa, 1980; Studerus, 1996). Generally, the theme of these studies involves how the dominant culture and language of the United States affects the language and behavior of Mexican-American Spanish speakers in a variety of ways. Nevertheless, information about border Spanish from the Mexican side of the international frontier is more scarce: there are relatively few studies about how U.S. culture, especially in terms of language, impacts Spanish speaking Mexicans living along the border in Mexico. The purpose of this study is to begin to address precisely this type of question.. 3.

(14) Problem 1.3. A specific inquiry into the possible impact of the English language on everyday border Spanish prompts three important questions. 1.. Does a discernable geographic area exist along the U.S.-Mexican border where a distinct variety of spoken Spanish, characterized by numerous English lexical borrowings, is used by native speakers?. 2.. What non-linguistic factors might also contribute to the use of such a variety of border Spanish? That is, Can a study be conducted which controls or limits sorne of the many extra-linguistic factors so that one variable, such as geography, can be statistically correlated to the use of the English lexical borrowings?. 3.. How can the use of English lexical borrowings, and the non-linguistic variables, be measured such that the measurement provides possibilities for broader interpretation?. The problem here is the scope of the phenomena and the variety of factors that are at play in this socio-cultural reality. From a sociolinguistic perspective, one must determine what linguistic items should be measured, and how their use proves (or disproves) the presence of a unique Spanish language variety. Most sociologists and border studies experts will not argue with the belief that the culture along both si des of the U.S.-Mexico border is unique, and somewhat distinct from the non-border cultures of both countries (Alvarez, 1995). The purpose of this study is to attempt to represent, in a specific and concrete fashion, one linguistic aspect that makes Mexican border culture unique. A study ofthe presence of English lexicon in native speech requires an extensive lexical sample of Spanish speaking Mexican natives from the border region. A large sample from different geographical locations, at distinct distances from border, might. 4.

(15) provide a broad view of the use of English lexical items in border Spanish. Further, a focused selection of subjects from each geographic site might help explain why or how English lexical borrowing occurs in the border region. Thus, a written questionnaire testing the knowledge and use of 50 borrowed English lexical items, or anglicisms, was administered to 300 native Spanish speakers from Sonora. Of this sample, one-fourth (75) were taken from Agua Prieta, one-fourth from Magdelena, and one-fourth from Caborca, ali towns at varying distances from the U.S. border and considered border region communities. The final fourth of the sample was taken from Navajoa, Sonora, a community over 600 kilometers from the U.S. border and not considered a border region town. Using a method that asks for synonyms for common standard Spanish words, the questionnaire sought to measure the extent to which Sonoran speakers use anglicisms in their daily spoken Spanish. In addition, the questionnaire elicited sociological data related to six other non-linguistic factors, in order to attempt to assess the relative importance of geography in the use of anglicisms in spoken Spanish. These factors were: age, gender, use of computer technology (specifically the internet), cable and satellite television viewing, time spent in the United States, and formal English language instruction. In order to narrow the focus of the study, the questionnaire was only applied to public high school students between the ages of 16 and 18. Focusing the sample in terms of age and economic background made data collection more efficient, and minimized the non-linguistic factors because ali of the participants had similar demographic profiles. The questionnaires were administered during the month ofDecember, 1999 by a team of native Sonorans under my direction. The data were analyzed, descriptively and inferentially, using the SPSS statistical software package version 7.5. Statistical. 5.

(16) information presented included simple numerical calculations of frequency and usage, cross-tabulations, and t-test analysis of statistical significance.. Hypothesis 1.4. This study posits two hypotheses. 1.. The use of borrowed English lexicon in Sonoran border Spanish is significant as compared to other geographic areas.. 2.. The frequency of usage of English lexicon is related to the speakers proximity to the U.S.-Mexico international border.. Moreover, this study posits that English language classes, number of days spent in the United States, use of computers, intemet, and cable television will not emerge as decisive factors in the use of anglicisms. Rather, geography will emerge as the key non-linguistic factor in determining the frequency of anglicisms in the speech of Sonora high school students.. Relevance 1.5. The importance of this study rests in the implications it may hold for understanding border communities and their unique varieties of language, as well as for foreign language teaching. The demographic data gathered may prove useful for sociolinguists, linguists, and experts in Spanish language and culture. Confirmation of the hypotheses would lend weight to the theory that the U.S.-Mexican border is a unique culture in itself, and must be treated so in socio-political terms. Identification of a distinct Spanish variety along the border would also benefit the residents of this region because it would confirm a unique cultural status, thereby affirming their language and culture, rather than stigmatizing it. Moreover, this inforrnation could benefit ESL theory and instruction, particularly in Mexico and its border classrooms. lt may benefit second. 6.

(17) language acquisition theory in general, especially in light of the increasing amount of people who speak mixed-languages as a result of globalization. This research might also be of interest to the State govemment, as well as educational administrators in border areas, in terms of language planning. Finally, this theme has global interest as well. Through technology, the world is becoming smaller, and, increasingly, peoples are encountering other cultures and languages. Ali govemments and cultures should have an interest in how linguistic professionals will identify and manage these language confrontations far the benefit of everyone. The study of border varieties of Spanish and their implications far ESL instruction are justified far three reasons. First, these linguistic communities are growing atan increasing rate and their value and presence must be taken into account, both socially and educationally. Second, cultures are growing more universal, and English is the language ofthe world: knowledge of English will be the prerequisite far membership in the global community in the next generation. Third, few similar studies have been done to date, and the field is relatively new and unexplored.. Outline 1.6. In arder to accomplish the objectives of the present study this paper has been divided into seven distinct chapters. The succeeding chapters are organized in the fallowing manner. Chapter II, Background and Theory, reviews the relevant sociolinguistic and dialectological studies. Chapter III provides the concomitant Background and Theory far the English language and ESL theory. Chapter IV presents the Methods of data collection. Chapter V is concerned with the presentation and interpretation of the Results of the research. Chapter VI Discusses the results and presents the Conclusions of the study. Finally, Chapter VII elaborates on the Implications of the study far Second Language Education in Mexico. Included here are. 7.

(18) sorne ideas for Further Research which the present study suggests. A final section of References and the Appendix conclude the paper.. 8.

(19) CHAPTERII. Background and Theoretical Considerations: Sociolinguistics. 2. The linguistic aspect of this research project is based in two areas: sociolinguistics and dialectology. The following is a brief review ofthe issues, theories, and studies related to the present research. The chapter is divided into the following six parts: introduction to sociolinguistics, dialectology, lexical dialectological studies, review of lexical dialectology, lexical studies of English borrowings in the Spanish language, and a summary.. Introduction to Sociolinguistics 2.1. Sociolinguistics is based on the beliefthat language is inexorably related to society, culture and context (Trudgill, 1974). Researchers have realized only recently that sociolinguistics reveals much not only about language, but also about society and human beings. As Trudgill (1974) states: "A study of language totally without reference to its social context inevitably leads to the om ission of sorne of the more complex and interesting aspects of language and to the loss of opportunities for further theoretical progress" (p. 32). The formal study of linguistics and society did not become widespread until the 1970s. The novelty of the field has meant, inevitably, that sociolinguistics has had to fight for acceptability. For example, linguists like Bloomfield and Labov recognized the importance of examining language in its social context, but their work has not been fully accepted by theoretical linguists like those from the Chomskean school (Hudson, 1980; Lastra, 1992). Nevertheless, many linguists believe that any study of. 9.

(20) language cannot occur without consideration ofthe speaker and the social context and, thus, traditional linguistics must go hand-in-hand with sociolinguistics (Hudson, 1980). Sociolinguistics begins with a personal experience of language first, and a collection of data second (Hudson, 1980). lt is a difference of emphasis based on the beliefthat the study of human speech must be conducted in relation to human beings in order to include the possibility of finding social explanations for the structures and use of language (Hudson, 1980; Trudgill, 1974 ). In this sen se, as Hudson ( 1980) points out, the proper object of sociolinguistics is not theory, but everyday (spoken) speech and language use. Thus, for example, sociolinguistics questions the distinction between Dutch and German along sorne parts of their respective international border because speakers can communicate easily with one another. Likewise, it questions the shared categorization of the language spoken by African-Americans living in Detroit and Welshman in Wales as English because these two groups of speakers cannot communicate effectively (Hudson, 1980). This scientific approach based on realism is further demonstrated in the notion of dialect. Sociolinguistics holds that a language dialect refers to lexical, grammatical, and/or phonetic differences within languages (Hudson, 1980). Moreover, each version or variety of the language is as legitimate as any other: there is no such thing as a standard variety of English in the sense that the term refers to value or superiority. A standard variety indicates a dialect chosen as a reference point for linguistic characteristics and functions, but does not represent linguistic superiority (Hudson, 1980). Sociolinguistics, then, claims that the speech community is crucial to understanding the language of the speakers (Hudson, 1980; Trudgill, 1974; Lastra, 1992). According to Hudson ( 1980) and Trudgill ( 1974 ), identifying a specific speech community and its unique language variety are basic tasks in sociolinguistic work. The socio-cultural factors that sociolinguistics may take into account in the attempt to identify. 10.

(21) a speech community include, but are not limited to: socio-economic status, ethnicity, age, gender, geography, nationality, and context. Bloomfield (1933) developed the idea that, if speech communities can be delimited, then they can be studied in terms of unique linguistic features that then define and delimit particular linguistic varieties and boundaries. In general, there are two techniques for the collection of sociolinguistic data: the recorded oral interview, and the questionnaire. Despite the fact that language differences are constituted by many linguistic factors, most sociolinguistic work (e.g., Labov, 1972; Chesire, 1982) has been concemed with phonology: the examination of differences and change in sounds between language varieties. Thus, the former method is more common. Basically, an interviewer elicits speech from a subject, usually through a non-directed casual conversation, and records the speech using a tape recorder. The speech sample is then transcribed and analyzed for the linguistic variant to be studied (Hudson, 1980). In order to do this properly the interviewer(s) must record literally hundreds of hours of speech to collect enough examples ofthe linguistic variant under study. In many cases, hours of recorded speech may produce only a few examples ofthe variant sound or word that the researcher is looking for. As a consequence, this type of research is limited to a few, well-funded and established linguists. Sometimes, as in the case of the Linguistic Atlas ofNew England (1939-43), this task can take seores of researchers years to complete. Dueto the impractical nature of this kind of data collection and analysis for short term or very specific studies (as in the case of a dissertation, for example), sociolinguists' have developed a variety of efficient techniques to provoke and elicit the speech they wish to study. These techniques fall into two categories: direct and indirect questioning. Chambers and Trudgill (1980) explained the differences between the two techniques. A direct question might ask: "what do you calla 'cup'." An indirect question is somewhat. 11.

(22) more subtle, and resembles questions like: "What do you sweeten coffee with?" (seeking to elicit the word "sugar" from the subject), or "What can you make from milk?" (Chambers and Trudgill, 1983). With Labov (1972) the sociolinguist became more sophisticated in the attempt to record natural speech, and thus minimizing the problem of the observer' s paradox. In a famous sociolinguistic study, Labov (1972) examined the pronunciation ofthe phonetic variant of /r/ in New York City by visiting department stores and asking clerks where an item was located (knowing it was located on the "faurth floor"). He then privately transcribed what he heard. In this fashion he was able to make sorne interesting revelations about the use of the linguistic variant in question. Although not used in this famous case, tape recording of speech seems to be the methodology of choice by most sociolinguists studying phonological variants of language. Another accepted methodology far sociolinguistic research is the questionnaire, either oral or written. The written questionnaire has the advantage of being more efficient and practica! than the recorded interview. The written questionnaire dates to the genesis of sociolinguistics itself in the 19th century. French and German linguists used the postal system to collect data from school masters and public officials (Chambers and Trudgill, 1980). In a sense, the written questionnaire and the recorded interview are similar: both tend to ask similar questions and, theoretically, elicit similar infarmation. Sociolinguistics and Spanish 2.1.1. The amount of sociolinguistic research of Spanish is notas substantial as that far English. A number ofthe current studies of Spanish dialectology, far example, are concerned with the language as it is spoken in the United States (Galindo, 1996; Penalosa, 1980). Included among these are two studies of mood variability (specifically, the use of the subjunctive) in Spanish (Studerus, 1996; Escamilla, 1982). Both studies used a written questionnaire, applied to Mexican-Americans living in Texas, to determine. 12.

(23) if, and to what extent, the use of the subjunctive in the Spanish spoken by these speakers was affected by exposure to the English language. Interestingly, both studies concluded that the Spanish spoken in Texas constitutes a unique dialect or variety of Spanish because of the extra-Iinguistic factors these speakers are exposed to. In other words, these studies claimed that the use of the subjunctive by Spanish speakers in Texas tends to decrease in relation to the time they have lived in the United States (Escamilla, 1982; Studerus, 1996). Another representative example of a sociolinguistic study of Spanish was that conducted by Lope Blanch ( 1970) on the different dialect zones of Mexico. This series of reports attempted to expand on a phonological study of Mexican territory conducted by Ureña in 1921. Ureña' s study distinguished between six dialect zones in Mexico: the north, the center, the gulf coast, the south, the Yucatan region, and Chiapas. Lope Blanch and his team administered a written questionnaire, which included more than 700 linguistic problems of syntax and grammar, to almost 500 subjects in 20 different cities in Mexico. This survey was administered both in person and vía correspondence over several years. In addition to the written questionnaire, the spoken speech of six subjects from each locale was recorded using the undirected dialogue method, and then analyzed for phonology in order to "corroborate and amplify the inforrnation obtained in the questionnaires" (p. 5. Note: ali translations are mine unless otherwise indicated). The conclusion confirrned Ureña' s demarcation of dialect zones in Mexico (Lope Blanch, 1971 ). Unfortunately, these studies failed to address, other than in passing, the possibility of a unique border dialect zone within the north dialect zone. This study does not lend itself to very accurate or reliable data or conclusions about specific dialects and variants of Spanish because the sample size was too narrow for the geographic areas under examination.. 13.

(24) Another seminal study of sociolinguistics that has particular relevance to the present research was conducted by Hensey ( 1972). Hensey examined the language contact zone on the Brazilian-Uruguayan border in terms of bilingualism, border communities, and linguistic interference in and between Spanish and Portuguese. Using different methods, including several types of written questionnaires, Hensey concluded that linguistic and cultural influence operates both directions on the border communities he studied. That is, Brazilian border communities use a style of Portuguese influenced by Spanish, and Uruguayan border communities use a style of Spanish influenced by Portuguese. Hensey' s study ( 1972) is important for three reasons. First, in the study of lexical borrowings between these border communities and their respective languages, a written questionnaire, utilizing pictures and drawings to elicit responses, was used. Second, it was one of the first studies to demonstrate the components of border dialects. And third, it attempted to demonstrate the connection between linguistic and cultural elements. That is, Hensey posited linkages between border dialect communities and their traditions and values (as seen in, for example, literature), which non-border dialect communities did not share. The weakness of this study, at least compared to the present research, is the lexical similarity of Spanish and Portuguese, which, as Hensey himself admits, share up to 90% of the same lexicon.. Dialectology 2.2. The present study seeks to identify a unique speech community along the border between Mexico and the United States (on the Mexican side). lt examines the characteristics of a Spanish variety which incorporates the use of English language vocabulary in the daily speech of its speakers. This type of study falls under the category of a branch of sociolinguistics called dialect geography or simply dialectology (Chambers. 14.

(25) and Trudgill, 1980). As Trudgill (1974) explained, geographical features such as distance and barriers affect the progress and path of linguistic change. Dialectology attempts to measure linguistic variables in terms of areas and boundaries, and it represents them physically on maps or charts. As Chambers and Trudgill (1980) showed, dialectological maps plot each individual use of a particular variable on a map, as compared to the use of contrary variables. These maps usually include lines between the two areas to show where the variable is generally used and where it is not. These geographic boundaries are called isoglosses. One theory used to explain much of dialect geography is called the wave theory which, as its name implies, claims that linguistic change emits from a certain geographical locus (for whatever reason), and spreads outward from that area (see Bailey, 1973). Often a dialectological study will attempt to representa linguistic variable not only in tenns of geography, but also as it is related to one or more other sociological factors, such as age or socio-economic status. That is, a study that focuses on the interaction between independent (sociological) variables and linguistic variables. This trend in dialectology is characterized by studies of urban communities of speakers (Labov, 1972; Sankoff, 1972). Examples of representative studies in this field include those conducted for the Linguistic Atlas ofNew England (Kurath, Hanley, Bloch and Lowman, 1939-43), which discovered a distinct three-way division of lexical and phonetic dialects in Massachusetts. By conducting surveys throughout the state, it was discovered that most speakers from the eastern third of the state u sed one set of names and pronunciations for specific items and concepts, while the rest of the state used another. F or example, the concept of a pancake in one part of the state was normally termed fritter, while the term griddle-cake was used in another part. The tenn "normally" was used relatively: the study showed. 15.

(26) various usages of terms but distinguished a definite preference of usage by simply considering greater number of examples of usage. Another good example of dialectology is provided by Chesire ( 1982) in her analysis ofthe morphological and syntactic differences between standard English and the English spoken in and around Reading, England. In this study, the author recorded the speech of working-class adolescents while they were playing ata public playground. This research attempted to eliminate as much non-linguistic variation (independent factors) as possible. Chesire claimed to have "eliminated" the "better-known aspects of sociolinguistic variation," namely age, sex, economic class, topic, context, and values by recording children playing ata working class playground who were "roughly" the same age and who "shared a number of common values and activities" (p. 5). By comparing the childrens' use ofthe pre-established Iist of morphemes and syntax with standard English, the author attempted to make general claims about the dialect spoken in Reading. This method for classifying and controlling non-Iinguistic variables is ambiguous because it assumes certain demographic and sociological characteristics ofthe participants simply by their presence in a certain location. No concrete demographic data about the children was collected by Chesire and, therefore, the results of her study are not as conclusive.. Lexical Dialectological Studies 2.3. Sociolinguistic studies focusing on lexicon are less common in comparison to their counterparts in phonology or syntax. According to sorne of the leaders in the field of sociolinguistics (e.g., Trudgill, 1974), the sub-field itselfhas an ambiguous presence in most sociolinguistic texts. A prime example is Lope Blanch's text Estudios Sobre el Español de México ( 1991 ). This text contains three main sections, including the Introduction, Phonetics, and Grammar, but only mentions Spanish lexicon in passing. In. 16.

(27) discussing the archaic nature of the Spanish spoken in Mexico as compared to Spain, Lope Blanch mentioned that this "archaism is most evident in the lexical terrain. (Words) forgotten in the peninsula maintain their vitality in Mexico"(p. 14). He then proceeded to list sorne of the lexical items still used in Mexico but not in Spain, for example: lindo; pararse; andprieto (p. 14). The author mentioned lexicon only one other time, in the discussion of the influence of indigenous languages and speakers on Spanish. Here, again, he listed sorne words used in Mexican Spanish, but not in Spain, which are derived from indigenous lexemes, such as: chapulín and milpa (p. 29). Where and how this small amount of information was obtained is left unsaid. Curiously, the entire subject of lexical study in the Spanish of Mexico is relegated to a few lines. The impression retained by the reader is that vocabulary is either so obvious that it should be understood, or so unimportant that it does not merit mention. This imprecision is also reflected in the English language studies, as well as in the English language textbooks on dialectology. For example, in Trudgill's important introductory text on sociolinguistics (1974), the field of lexical study is mentioned twice, and only once in relation to dialect geography. In speaking of linguistic innovations and language boundaries, Trudgill stated that lexical items spread according to the field in which a particular language tends to dominate (p. 177). Thus, he pointed out, English words have come to dominate science and technology vocabulary in many languages. Unfortunately, Trudgill does not expand on the concepts oflexical loaning and borrowing beyond this. Hudson (1980) is only a little better. In his text on sociolinguistics, two pages are dedicated to lexical borrowing and loan translations in the chapter on varieties of language. Interestingly, Hudson explained how sorne words lose their foreign pronunciation when adopted by another language, while other lexical items may be used only as models by which native constructions are created. The passage continued on to imply that linguistic borrowing from one language to another entails more than. 17.

(28) convenience, as sorne other authors (e.g., Hidalgo, 1983) have claimed, but may involve syntax and morphology. Hudson concluded this brief account with the provocative question: "Are there any aspects of language which cannot be borrowed?"(p. 60). Unfortunately, this author leaves the reader wondering why there are not more studies demonstrating specifically why and how this borrowing is being done. Poplack, Sankoff, and Miller ( 1988) studied the French spoken in the OttawaHull region of Canada in terms ofthe nature and impact of English on speakers from five communities. Going door to door, this team obtained over 270 hours ofrecorded speech that were then transcribed with English words and phrases noted by English orthography. This study is important for its in-depth delimitation and classification of dialectological terms, like borrowing, code-switching, and loan words. The authors concluded that active use of English vocabulary by these native French speakers was less than I percent of the total corpus, and that most of these were momentary or faddish borrowings that were not used by the majority of the subjects, nor had any long-term impact on French.. Review of Lexical Dialectology 2.4. In spite of the work of researchers like Poplock, Sankoff, and Miller ( 1988), the general body of dialectological work fails to adequately answer questions about how lexical studies are done and why they are significant. The two best sources for information about lexical dialectological theory and terminology that I have found are Sociolinguística para hispanoamericanos (1992) by Yolanda Lastra, and Bilingualism ( 1989) by Suzanna Romaine. Lastra' s chapter on Languages in Contact and Romaine' s on The Bilingual Speech Community elaborated the relevant terminology and distinctions related to lexical studies. Unfortunately, though both texts provide excellent and detailed information, it seems that they both confirm the ambiguity and lack of consensus in a fledgling academic field. As Romaine remarked, questions of language interference and. 18.

(29) borrowing are the most commonly described dialectological phenomena, but also the most hotly debated (p. 50). Citing Weinrich (1953), both Lastra (1992) and Romaine (l 989) began with the term interference: meaning a deviation, either phonological, grammatical, or lexical, from the linguistic norm dueto a bilingual speakers' familiarity with more than one language. In other words, the process involving the introduction of fareign elements, including lexical items, into the structure of a language. Unfartunately, there is not universal acceptance of this term. Romaine cited a series of other authors who use different tenns to refer to these two same concepts. Most authors seem to imply, however, that linguistic interference between two languages is originally caused by bilingual speakers. The significant issue far the present study is how and why non-bilingual speakers use fareign lexical items in their daily speech. Fortunately, Weinrich seems to provide a clue as to how to resolve this question in his claim that there is a need far further study to determine whether interference is caused linguistically when languages are in contact via bilingual individuals, or whether it is caused by non-linguistic factors of the socio-cultural nature. Here the notions of languages in contact and cultures in contact become intimately interrelated, as sociolinguistic theory demands. In arder to further define the notion of interference, Lastra ( 1992) presented the term linguistic borrowing (or transfer) and the sub-tenns momentary borrowing and established borrowing. The distinction between the sub-terms is crucial far the present study: the farmer is a type of interference used by a bilingual speaker in spoken speech, the latter a modification in the language itself. Haugen (l 950), in one of the first attempts to categorize lexical influence between languages in contact, made a congruent distinction: words that are fully assimilated into a language (phonologically and morphologically) are not the same as partially assimilated words. The fanner are called loanwords, while the latter are words used by mono lingual speakers, who may not even. 19.

(30) be aware of their foreign origin. Poplock and Sankoff ( 1984) made a more specific distinction in this respect. They claimed that momentary borrowing (or nance borrowing, as they term it) by bilingual individuals occurs when one cannot remember the precise word in his native language and substitutes a foreign word in its place. How and why bilingual speakers switch from one language variety to another, called code-switching (or alternation), is not agreed u pon by ali scholars. Far example, Hudson ( 1980) claimed code-switching occurs only among members ofthe same community, while Lastra disagreed with this point. Sorne scholars, like Romaine (1989), believe that codeswitching can occur between different varieties of the same language or even between styles of speech within the same variety. This understanding of code-switching stands in contrast to the notion of diglossia, in which the speaker uses one distinct language or another depending on the social context (Romaine, 1989). The result is a general confusion of terminology where the use of a single utterance from another language can be termed mixing, tag switching, or lexical borrowing depending on the author and the study involved (Romaine, 1989). What these disparate theories share is an understanding of the concepts of bilingual and bilingualism. How much of another language must a speaker know to be considered bilingual? Can one be a "passive bilingual" (Romaine, 1989) if one can understand a dialect similar to one' s own? Can a speaker be an unconscious or unwilling bilingual if one experiences linguistic interference of any type? As Lastra ( 1994) pointed out, an established linguistic borrowing is easier to study because it should be recurrent, and should spread amongst many speakers (implying nonbilingual speakers), rather than existing only in a particular moment with a particular speaker. These are sociolinguistic concerns which have yet to be clearly worked-out, especially in terms of pedagogy and language instruction. There are two kinds of lexical borrowing ( or lexical transference ). In the first type, termed borrowed form, the morphemes of the word of one language are adapted to. 20.

(31) the new language. In the second type, termed extension of meaning, the borrowed lexical item assumes a new or additional meaning in the borrowing language (Lastra, 1992). An example of the former is the word holishmok in German, which comes from the exclamation in English, "holy smoke!" An example of the latter is the word ministro in Spanish, which has come to have the additional meaning of protestant clergy dueto the influence of English (Lastra, 1992; Romaine, 1989). Borrowing can take semantic or grammatical forms as well, but such issues are beyond the scope of the present paper. An important distinction for the present study is that between code-switching and lexical borrowing. Though these processes may be related ( depending on how one understands bilingual and the role of the bilingual individual when languages are in contact), sorne scholars ( e.g., Lastra, 1992) claim there is a difference that is manifested in pronunciation. Leo un magazine, in which the noun is pronounced using standard English, is an example of code-switching. In contrast, Leo un lmayasín/ is an example of lexical borrowing (Lastra, 1992). Lastra stated: "Monolinguals use established borrowings since momentary borrowings are employed only by bilingual individuals and are not always phonetically integrated (in the borrowing language). (Momentary borrowings) are a kind of alternation of only one word, generally a noun" (p. 192). Romaine (1989) concurred with similar words: (Bilingual) speakers rely heavily on nonce borrowing (though) in principie, the whole lexicon of the two languages is at the disposal of the proficient bilingual...(These nonce borrowings) provide a source of potentially integratable items for other less proficient bilingual and monolingual members to draw on (p. 63). The present study attempts to provide more information with respect to precisely whether or not monolinguals use momentary lexical borrowings or ifthey are limited to bilingual speakers. This task may be difficult in the sense that is has not been readily. 21. 000820.

(32) attempted. According to Lastra, "The role of bilinguals as opposed to monolinguals ... in the dissemination of (lexical) borrowings, has not been empirically studied"(p. 189). Romaine ( 1989), citing Ha ugen ( 1953 ), Poplock and Sankoff ( 1984), and others claimed that "borrowed items seem to have an uncertain linguistic status ... each individual (speaker) may adopt it to varying degrees ... or in different form from one occurrence to the next"(p. 58). In order to begin to understand how linguistic borrowing takes place, one must consider more thanjust linguistic phenomena. The present study seeks to considera specific demographic group, and explicit extra-linguistic variables, in order to focus the ambiguous problem of lexical dialectology. The objective is to provide manageable information which may prove useful for language education theory.. Lexical Studies of English Borrowings in Spanish 2.5. The quantity of studies dealing with English lexical borrowings in Spanish are few and, in general, not well done. It is difficult to account for this paucity of research, especially in light ofthe increasing significance of contact between U.S. culture and Mexican culture along one ofthe world's largest bi-national frontiers. In my research for the present study, I have encountered three similar studies that are reviewed next. Margarita Hidalgo conducted the first of these studies for her Ph.D. dissertation in 1983. The study, titled Language Use and Language Attitudes in Juarez, Mexico, applied a written questionnaire to 85 residents of Juarez in arder to elicit information about codeswitching. As the author stated, the purpose of her study was to investigate "the specific domains and frequency with which English is used in Juarez, and (to explore) the use of Spanglish" (p. vii). Hidalgo (1983) made an important distinction between informal language setting and usage, and formal language settings and usage, which served as a basis for her general position about the use of English by Juarez residents:. 22.

(33) The use of English (lexical borrowings) is restricted to informal situations which enhance a relaxed atmosphere and tone of conversation. This sporadic, informal use of English is definitely a style ofthe young adults under thirty-five who have studied English formally for a number of years (p. 48).. Further, this study claimed that English borrowing is restricted by very specific domains and only infrequently occurs regularly between Mexicans. In conclusion, Hidalgo (1983) claimed that her study shows that English use by Mexicans in Juarez was related to socioeconomic status and the environment of the border, which facilitates exposure to informal sources of English language use. Unfortunately, this study has a number of serious errors which make the data related to the use of English borrowings by Mexicans questionable. For example, the questionnaire has no specific linguistic aspects that deal with English. Section 2 of the questionnaire, "intended to measure the Subjects' informal use of English," was "a comprised measure based on approximations of functions ofthis language and its domains" (Hidalgo, 1983, p. 50). Thus, rather than any sort of linguistic questions, the questionnaire consisted of questions such as: "12. How often do you write in English" and "13. In general, your knowledge of English is ... " (p. 227). At severa) points the author mentioned common anglicisms used by Mexicans and, at one point, even provided a chart that listed 11 items with their popular version, English source, and whether their use was stigmatized in Spanish. However, these data were not obtained from the questionnaire but from "discussions," which occurred apart from the questionnaire, with sorne of the subjects (p. 130). Additional problems with the methodology include the manner in which the subjects were selected for study. As Hidalgo (1983) indicated on page 52, subjects were. 23.

(34) selected dueto "convenience" and "willingness to participate" from visits to stores and restaurants. 1t is difficult to accept, scientifically, Hidalgo' s inductive conclusions about English lexical borrowings for twofold reasons. First, the sample size was too small since it represented a variety of ages and economic classes. Second, the method for subject selection was problematic: subjects not willing to participate were excluded. Granted, the purpose of Hidalgo's study was more than the use of language, it also hadas a goal exploring the attitudes Mexicans had toward languages and their use. But there is a dubious relationship between the two. As she stated herself: "There is nota complete correspondence between language attitudes and language behavior" (p. 26). Nevertheless, it is clear that this study failed to understand or capture the nature of the use of English lexical borrowings by Spanish-speaking Mexicans on the border. As Hidalgo admitted, "The use of English with other Mexicans is an exceptional, incongruent fonn of behavior whose parameters deserve a more cautious and exhaustive study" (p. 69). Huyke Freiría conducted a similar study which is included in a text edited by Lope Blanch called Estudios Sobre el Español Hablado en las Principales Ciudades de America ( 1977). This study dealt with the presence of anglicisms in San Juan, Puerto Rico. lts purpose was to investigate the density of anglicisms in the "standard educated linguistica" of San Juan in four distinct lexical areas: transportation and travel, mass communication, entertainment, and the office (Lope Blanch, 1977). In order to execute the study, Huyke used an oral questionnaire consisting of open-ended questions that were designed to provoke responses of the English lexical words in question. For example, in the area of transportation, the participants were asked to name "those words that you associate or use with 'train'" (Lope Blanch, 1977, p. 65). For her study, Huyke defined an "anglicism" as fulfilling one of the following criteria: a word whose fonn - whether phonetically adopted to Spanish or in its original fonn - comes from English; or, a word. 24.

(35) whose meaning is accepted in Spanish but comes from English (Lope Blanch, 1977, p. 69). In other words, check and chequear were both considered anglicisms for this study. The results revealed that of the entire lexical corpus elicited from the subjects, only 10.4% were anglicisms, as defined using the broad criteria cited above (Lope Blanch, 1977, p. 71). The study concluded with a detailed list of ali the English lexical items used and their individual frequency, which proved useful for the selection of items used in the present study. Despite the interesting distribution of lexical infonnation provided for by Huyke in her series of charts and lists, her study lacks significant impact in the field of lexical dialectology for two reasons. First, the number of subjects and their breadth of demographic representation made any inductive conclusions about speech in San Juan dubious. Huyke used only 12 subjects, which included persons in age from 26 to 58 years (Lope Blanch, 1977, p. 66). Moreover, other than information about education levels, no other sociological information was provided. Second, the scope and results of the research were misleading. The stated objective of the study was the density of anglicisms present in the educated speech of San Juan; therefore, ali of the subjects possessed at least one university degree as a criterion for participating in the study. Unfortunately, as many sociolinguists claim (e.g., Trudgill, 1977), non-standard speech occurs more frequently and naturally in less formal circumstances. Thus, to study a feature of non-standard speech in educated Spanish, via a formal questionnaire, seems contradictory from a methodological and theoretical standpoint. Huyke herself made an enigmatic statement in this regard on page 65: "Pero es poco probable que se utilicen en. conversaciones cotidianas." This accounts for the seemingly low percentage of density of anglicisms in the speech of San Juan, a city that has as one of its official languages English. The present study hopes to avoid these errors with a much larger sample of. 25.

(36) subjects, a more specific sociological focus, and an emphasis on daily, informal, spoken Spanish. A third study far consideration is that conducted by Diana Alicia Bustamante far a Ph.D. dissertation (1987), titled Choice of Language by Individuals in Border and Interior Regions: A Study of Media Impact on Mexican lssues. In her discussion of Spanish and the use of anglicisms, Bustamante made sorne startling claims. Using as basis a study conducted by a Mexican government agency, Bustamante commented on the use of anglicisms along the border as compared to the interior of Mexico: "Interior cities show a higher use score on the use of Anglicisms than border cities ... the only difference between the two regions is dueto social class, not region (p. 28)." These data were based on a study sponsored by the National Commission far the Defense of the Spanish Language and conducted by the Center far the Study of Northern Mexican Border (CENOFEX) in 1982. Unfortunately, CENOFEX no longer exists and their building in Tiajuana where CENOFEX was located, no longer claims to have the study it conducted. Moreover, as Bustamante herself admitted on pp. 22-23, the Commission in question was created with the purpose of eradicating and stigmatizing the use of English in Mexican Spanish. This problematic example aside, Bustamante's research contains other methodological errors and sorne dubious research. To begin, the method used to measure language use, as in the study conducted by Hidalgo ( 1983), does not correspond to any real linguistic information, despite its claims. Far example, the questionnaire included the question, "What is the frequency with which you have contact with the following means of communication?" Then it listed four aspects of media and asked subjects to mark their use in English, Spanish, from the USA, and from Mexico (Bustamante, 1987, p. 32). The connection between language choice and use was not based on linguistic observation. In addition, the data base used far her conclusions was problematic because the cities selected far study are not representative. 26.

(37) of the Spanish of Mexico and its dialect zones as defined by Lope Blanch (1991 ). For example, Mexico City and Acapulco, representing the interior of Mexico, ranked highest in use of English lexical items, while Matamoros (on the Texas border) ranked last (Bustamante, 1987). Unfortunately, the lexical fields chosen for the study, including business and travel, are naturally more common in these popular tourist cities that have a high number of foreign visitors. Finally, the political agenda of the agency that provided the data used by Bustamante, explicitly conducted to defend and protect the use of standard Spanish in Mexico, tainted her later claims. One of the objectives ofthe present study ofthe use of English lexical items in border Spanish is to disprove the notion that border Spanish does not contain a higher density of anglicisms than Spanish in the interior of Mexico.. Summary 2.6. The purpose of this review of sociolinguistic theory and research was twofold. First, it helped locate and focus the present study in terms of methodology and objectives. Sociolinguistic studies attempt to examine how language is used by speakers in the context of everyday life. Questionnaires or tape recordings provide information about the language used by speakers. Then this linguistic information is analyzed for selected variables, or in terms of specific sociological factors. Phonological studies dominate sociolinguistic work, but other fields, such as dialectology, also constitute sociolinguistics. The second purpose of this review was to demonstrate the paucity of studies related to the use of anglicisms in Mexican Spanish, and to analyze their content and quality. No study dedicated exclusively to the examination of the use of anglicisms by border Mexicans was identified in this research. Moreover, the four similar studies identified in this review contain questionable results dueto methodological problems.. 27.

(38) CHAPTERIII. Background and Theoretical Considerations: English as a Second Language. 3. The educational aspect of this paper is concerned with English as a Second Language (ESL) instruction. This chapter seeks to provide a brief review ofthe following themes as they pertain to the present research: the universalization of English, language planning and education, English as a Second Language leaming theory, and ESL vocabulary instruction theory. A summary concludes the chapter.. The Universalization of English, Language Planning and Education 3.1. The universalization ofthe English language signifies an unprecedented linguistic reality in the history of civilization: today it is used as a means of communication by more people than any other language ever (Kachru, 1996). As English becomes more universal, the diversity of English, in terms of dialects and styles, increases. Obvious examples of this process are seen in the dominance of English in fields like science and technology, international business and banking, aviation and tourism, and education at higher levels. However, most people fail to recognize or understand the nature of this reality and its implications. Goerge Steiner pointed out as early as the 1970s that the center ofthe English language has shifted away from its origins (Kachru, 1996). English is now a language of the world, rather than of justa particular culture or country. One scholar has even stated that "the native. 28.

(39) speaker is irrelevant" in the natural development of English asan international language (Widdowson, 1983, p. 382). Linguists who favor this view use the example of the elusive and changing English lexicon as evidence for the myth of a standard English language. These scholars, led by Widdowson, SavilleTroike, and Kachru, emphasize the unneeded and unwanted input of native speakers from England, the United States, or anywhere else in the development of English. English lexis, they point out, are constantly invented and adapted and cannot be contained in a standard lexicon. English vocabulary has so diversified that different groups of users have developed their own specialized lexicons for communal communicative functions (Widdowson, 1983). This understanding of the English language has important implications for linguistic proficiency and regulation. On the one hand, a speaker would be considered proficient to the extent that he possesses the language and makes it his own, rather than just submitting to standard dictates of form. On the other hand, English must be seen as self-regulating, "appropriate to different conditions of use" (Widdowson, 1983). Linguistically, English is characterized by its tolerance to (linguistic) variation and its multiplicity of standard dialects (Lastra, 1992), as opposed to, for example, French which is characterized by its identification to a particular culture and its inherent rigidity. This basic reality is reflected in the fact that there are four non-native speakers ofEnglish for every one native speaker (Kachru, 1996), and that English is recognized as the official language of at least 37 countries: "English is the only natural language that has considerably more non-native users than native users" (Lastra, 1992, p. 347).. 29.

(40) The impact ofthe universalization of English on foreign cultures, other languages, language learning, literature, society, politics, economics, and ideology have yet to be fully studied or understood. In his paper on World Englishes, Braj Kachru ( 1996) attempted to delimit how English is affected by, and affects, linguistically and culturally distinct contexts. Therein, the author also provided sorne clues as to how language instruction and language planning might be approached in the attempt to contend with this important phenomenon. Kachru identified this complex affective process by its reciproca! manifestations. One, called Englishization, refers to the process of change that English has initiated in the other languages ofthe world (p. 138). The other manifestation Kachru termed Acculturation ofEnglish, which refers to linguistic changes occurring in English as a result of contact with, and use by, different cultural groups (p. 138). This concept takes into account the variety of non-standard English dialects spoken around the globe and attempts to not only legitimize, but also embrace their existence. This term applies to the methods and approaches to ESL instruction that exist throughout the world and which, according to the author, need to be re-examined. Unfortunately, the global initiation of bilingualism in English, a true paradigm shift both linguistically and socially, has yet to provide any concomitantly new and adequate methodology for the study of its implications on language planning and bilingual education. The problems of language planning and language education seem clear enough at first glance. For example: Can language planning and control be exercised, or is the attempt futile or destructive? Does the diffusion of English imply the loss or death of other languages? Does a standard English exist and. 30.

(41) how should the varieties of English be compared and valued? Which English variety should be taught to second language leamers and who should teach it? What qualifications will the language instructor need? What language variety should be the medium of instruction? Should the attainment of native-like competence be the goal of ESL teaching or not? And, What type of language instruction is adequate or appropriate for new sociolinguistic contexts where ESL learning is occurring (Nichols, 1996)? However, these issues are not so easily resolved when placed in the context of non-Anglo, non-first world cultural concepts of power and politics. In Mexico, for example, the notion of a distinct and independent Mexican culture itself is invariably linked to the preservation of apure Spanish as the national tangue. In arder to confront this perceived problem the Mexican govemment has created the National Commission for the Defense ofthe Spanish Language (Comisión Naciónal Para La Defensa Del Idioma. Español), which has led to the attempt to provide sorne empirical research to verify the supposition that linguistic and cultural change is taking place in Mexico as a result of the influence of English and the bordering United States (Bustamante, 1987). This Commission led to the questionable study conducted by the Centro de Estudios Fronterizos Del Norte de Mexico (CEFNOMEX) cited in Chapter II. In addition, the Commission has led to publicity campaigns that ridicule the use of non-standard Spanish and play on the fears of average Mexicans (Bustammante, 1987). Mexican politicians seem to be influenced by doomsayers like Seda (1980), who have predicted the extinction of Puerto Rican culture and Spanish dueto English code-. 31.

(42) switching: a prophecy which is not supported by current sociolinguistic studies of Puerto Rican Spanish (e.g., see Lope Blanch, 1977). This fear of linguistic and, by extension, cultural contamination from Mexico's powerful northern neighbor influences paradigms of language teaching in Mexico. As the English language exerts ever increasing influence over Spanish via the speech patterns of Mexican youth, the govemment claims this interference may lead to fossilization of errors and subsequent nonstandard varieties of Spanish From the language educators perspective, the problem is twofold. First, the knowledge and use of non-standard varieties of the target language (English), which may differ from the instructor' s variety of English is an issue. Second, the question of which English variety is dictated by the curriculum: a pedagogical conundrum which must be addressed in the classroom. Ultimately, the fear is that the linguistic death ofMexican Spanish itself may result. The stance ofthe Mexican govemment, however, is misguided and not based on linguistic reality. As Romaine (1989) pointed out, language loss/death is not a real threat to the situation in Mexico because language switching and borrowing does not cause language loss: there is nota real connection between grammar competence and other linguistic competences, like lexical borrowing. Moreover, using schools as the principie agents of language control and arbitration are ineffective because linguistic interference is socially determined, not linguistically controlled (Romaine, 1989). In other words, any attempt to control the usage and development of Spanish must begin with the control of people and their behavior, a task which no govemment is capable of in any comprehensive sense (Wiley, 1996).. 32.

(43) The Mexican government would likely find more success in its language planning policy, especially with respect to the interference of the English language in the many varieties of spoken Spanish, if it assumed a stance oftolerance based on sociolinguistic reality. The first step would be to recognize non-standard varieties of Spanish as legitimate forms of communication that represent distinct cultures and societies. As Romaine ( 1989) pointed out, non-standard varieties are stigmatized in all countries. Various sociolinguists now promote tolerance in the classroom as the best method to promote social and linguistic variation (e.g., Hornberger, 1996; Rickford, 1996). Issues of linguistic prejudice and social inequality are directly related to the act of recognizing a regional linguistic variety as a legitimate mode of communication, both within and without the communities where it is used. Failure to do this may have a number of educational consequences related to ESL instruction. For example, Hornberger (1996) suggested that when educational planning takes into account the language community and its culture, the quality of language learning improves. Further, iflanguage instruction does not consider the cultural and linguistic varieties in the classroom, Hornberger warned, the sociological impact on the learner can be negative. For example, if only standard English vocabulary is taught in a classroom with learners who possess and use English lexical items in different formats, the learner will assume the hidden message that his use of these lexical items is inferior, less important, and less useful. And by extension, his native linguistic variety and even his culture assume these same characteristics (Hornberger, 1996).. 33.

(44) The informed sociolinguistic stance would be to legitimize ali varieties of Mexican Spanish and question the need and benefits of attempting to impose standard Spanish. Further, the claim of the superiority of standard Mexican Spanish would be revealed as a myth with no scientific basis. Finally, in terms of language planning, sociolinguistics would warn against the dangers oftight central control, and emphasize the benefits of maintaining the variety and richness of cultures within Mexican society. Lastra (1992) implied that language planning should be conducted for one reason: if a communication problem exists; then, control of a language must occur. However, in Mexico's case no such problem exists. In fact, one ofthe principie objectives of much language planning is lexical expansion in arder to communicate more effectively with industrialized nations and their languages, which is happening naturally in Spanish by, for example, the borrowing of English lexical items. Lastra also pointed out the need to study the effects of any language change or regularization on the groups being affected, something not being done in Mexico. At stake is the recognition and empowerment of the various geographic and linguistic cultures in Mexico, and, indeed, the success of Mexican society in general. As Hornberger (1996) stated: "Language and language use both shape and mediate young peoples' participation in educational opportunities, and, ultimately, their contribution, real and potential, to the larger society" (p. 452). In terms of language education, specifically ESL instruction, Mexico must develop new paradigms of pedagogy (method and materials) that respond to the new challenges that English lexical borrowing, and a wide variety of spoken Spanish varieties, present. Up to the present, this challenge has yet to. 34.

(45) be met, if even recognized. Lastra (1992) claimed that bilingual education in Mexico is considered non-existent or poor by ali scholars, and that there are no extant studies of bilingual education in Latin America. Zoreda ( I 996) suggested using popular texts from different cultures in the ESL classroom in order to foster a "creative understanding of the foreign culture" and language which would then "help students begin the critical process of discovering and questioning their own identities, preferences and subjectivities" (p. 3). She claimed that Mexicans educators must change the way they approach American culture and the English language in order to:. Rescue a rather fossilized college English curriculum with the purpose of upgrading it so it may contribute to the formation of graduates in Mexico as transcultural literates capable of confronting others cultures critically and simultaneously appreciating their own culture. We would then be working toward the end of irrational, chauvinistic policies of "in verse discrimination" toward foreign cultures (Zoreda, I 996, p. I ).. Many scholars concur with Zoreda, and have concluded that language teaching should occur in the learners' own variety, with an instructor who is a native speaker ofthat variety, and the variety of the target language should conform to the leamers linguistic variety and cultural context (e.g., Homberger, I 996; Ricker, I 996; and Nichols, 1996). Before this can be done, however, a sociolinguisitic study ofthe Spanish language and its dialects in Mexico is required. Before such studies. 35.

Figure

Documento similar

Taking into account that the tendency in Spanish schools is to establish a bilingual primary education system (Spanish and English), those students who do not major in English

Finally, Figure 4 presents the relationship between adjusted trade and distance for intra-national flows when we use highly disaggregated geographical units as origin and

Finally, Figure 4 presents the relationship between adjusted trade and dis- tance for intra-national flows when we use highly disaggregated geographical units as origin and

López & Morant ( 1991) have studied these differences, and although women also use swearwords and vulgar language, both their range and its use are limited: they

Las políticas represivas de la administración de Donald Trump hacia los migrantes, la manipulación del simbolismo jingoísta de la frontera y la reactivación de su más

However, little research has been carried out within the field of English literature as a pedagogic device for English as a foreign language (hereafter abbreviated as EFL) purposes

Native language referred to native English (NE), while non-native allowed for categories of English as a second language (ESL) speakers who have a non-English cultural background,

Trade finance enables companies to manage their cash flow and lower the risks involved in cross-border transactions by giving them access to financing that is particularly suited for