Student and Environmental Protests in Chile: The Role of Social Media

Texto completo

(2) 152. ANDRÉS SCHERMAN, ARTURO ARRIAGADA AND SEBASTIÁN VALENZUELA. theoretical discussion, we turn to the empirical analyses using a cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of young adults (School of Journalism Universidad Diego Portales & Feedback, 2011). We describe who protests and uses Facebook and Twitter, and we test the correlations between using social media and participation in the student and environmental movements in Chile in 2011. We conclude by discussing the contribution of our findings to current debates on citizenship, participation and new media.. The context of the 2011 protests in Chile Derided during most of the 1990s and early 2000s as an ‘indifferent’ and ‘politically disengaged’ group, Chilean students – both high school and university – demanded in 2011 through massive street protests that the government end for-profit universities, offer free higher education and improve the quality of the educational system in general. The leaders of the movements relied on social media, including Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, to communicate with the rest of the student body and amplify the voice of the demonstrations to attract media attention and public support. Thus, in similar fashion to developments in other countries (Bennett and Segerberg, 2012; Ekström and Östman, 2013), the diffusion of the Internet and social media has changed the way young people in Chile exert their citizenship, increasingly blurring the boundaries between online and offline political participation. At the same time, green movements mobilised youth against HidroAysén – a planned power plant in Chilean Patagonia – through large public demonstrations in Santiago, the capital city. Promoted by the Spanish company Endesa and the Chilean company Colbún, HidroAysén involved the construction of five plants on the Baker and Pascua rivers, flooding 5,910 hectares of pristine land, and installing a transmission line across most of the southern and central regions of Chile. The project, as could be expected, garnered the firm opposition of environmental groups. The strength and widespread nature of these social movements became evident on reviewing some of the results of the survey on Youth, Participation and Media Consumption 2011 (School of Journalism Universidad Diego Portales & Feedback, 2011) – an annual study carried out in the three most important urban centres in the country since 2009. According to this study, in 2012, 33 per cent of the population between 18 and 29 years old confirmed they had attended at least one public demonstration over the last 12 months – a figure that is more than double the response rates obtained in the 2009 and 2010 surveys for the same question.. Youth, participation and online media In step with the international trend, young people in Chile account for low participation levels in national politics. From 1988 to 2009, the levels of electoral participation of youth between 18 and 29 years old diminished from 35 to 9 per cent. Some authors believe this worldwide phenomenon of low electoral commitment reflects changes in the definition and individual practice of exercising citizenship. Bennett (2008) and Dalton (2008), among others, suggest that ‘obedient citizens’ are being replaced by ‘self-actualising citizens’. The former channel their political actions through more traditional forms of participation such as voting, whereas the latter do so through civic actions such as community work and non-conventional political activities like protesting, incorporating the use of digital technologies. © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(3) SOCIAL MEDIA AND PROTESTS IN CHILE. 153. As expected, the increasing use of online media for political issues has generated an academic debate on the connection between their use and the type of political behaviour adopted by young people (Xenos and Moy, 2007). The so-called ‘cyberoptimists’ adopt an instrumental vision of the Internet by suggesting that it decreases the costs of communication, association and participation (Rheingold, 2000). ‘Cyberpessimists’, on the contrary, argue that the use of the Internet drives people away from politics, public affairs and social life (Nie, 2001). However, this dichotomy ignores a more nuanced reality, where the consequences of online media in the political participation of individuals are contingent to the various contexts, uses and traits of people employing these media (Bimber, 2001, 2003; Kwak, Shah and Holbert, 2004; Shah, Kwak and Holbert, 2001). In other words, the effects of online technologies on the political behaviour of young people are mediated by specific uses (e.g. information versus entertainment) and moderated by predispositions. Prior research lends support to a more nuanced view of social media effects on political behaviour. Vitak et al. (2011) found that social network sites can impact psychological engagement, campaign recruitment and access to resources – all necessary ingredients for participation. Studying young people as well, Xenos, Vromen and Loader (2014) argued that social media use may influence engagement by interacting with individuals’ socialisation and emerging forms of citizenship. Specifically, these authors posited that exposure to social media – whether incidental or not – can increase participation for people raised in families where political discussion is usual. In addition, social media can moderate the relationship between new forms of citizenship (e.g. opinion expression in digital media, fighting for consumers’ rights, etc.) (Xenos, Vromen and Loader, 2014). In their study on adolescents, Ekström and Östman (2013) found that online and offline participation through social media was different depending on whether social media was used for consuming information, talking with others users, creating content or searching for entertainment. Bearing in mind these considerations, the meta-analysis developed by Boulianne (2009) using US data did not find any evidence to suggest that the use of technology and online services is related to a lower political commitment of people. On the contrary, a positive association exists between being exposed to online information and political participation (Owen, 2008; Raynes-Goldie and Walker, 2008; Valenzuela, 2013; Valenzuela, Park and Kee, 2009). In the case of Chilean youth, prior research has found a positive connection between the use of online platforms, including social media, and their level of participation in political and civic activities (Scherman and Arriagada, 2012; Scherman, Arriagada and Valenzuela, 2012). These results are consistent with studies carried out in other countries (see Bakker and De Vreese, 2011; Gil de Zúñiga and Valenzuela, 2011; Harlow, 2012).. Protests and the use of social media A study on social media begs the question of what social media is in the first place. Here we will rely on Ellison and Boyd’s (2013, p. 158) definition. According to the authors, social media are platforms ‘in which participants (1) have uniquely identifiable profiles that consist of user-supplied content, content provided by other users, and system-level data; (2) can publicly articulate connections that can be viewed and traversed by others; and (3) can consume, produce, and interact with streams of user-generated content’. Profiles allow users to obtain substantial information about the profile owners and their respective social networks, including personal trajectory, photographs, networks of contacts, and literary and musical tastes (Gil de Zúñiga, Jung and Valenzuela, 2012). Furthermore, © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(4) 154. ANDRÉS SCHERMAN, ARTURO ARRIAGADA AND SEBASTIÁN VALENZUELA. communication between users of social media can be either public (e.g. commenting on a user’s Facebook Wall) or private (e.g. chatting or internal messaging). Howard and Parks (2012) suggest that, in addition to these characteristics, social media consist of: the informational structure and necessary tools to produce and distribute content with individual value, but that reflect shared values; content in digital form of personal messages, news and ideas which are then converted into cultural products; and persons, organisations and industries that produce and consume technological tools and their content. Social media provide a wide variety of possibilities for promoting participation among youth, especially in protest demonstrations. By presenting online individuals’ offline social networks, websites such as Facebook or Twitter facilitate access to a large number of contacts, increasing the probability of reaching critical mass. The digital nature of these media diminishes the monetary cost involved in the mass distribution of information to mobilise individuals. Social media can also promote the construction of social and individual identity – information relevant to the protesting activity (Dalton, Sickle and Weldon, 2009) – enabling multiple channels for interpersonal feedback and peer acceptance and strengthening group standards. These sites can also operate as information centres. For example, Facebook users have a news feed that monitors their contacts with regular updates on what they are doing (Hargittai, 2007). Likewise, these services allow users to create and join groups with common interests. Hence, people belonging to social and political movements can receive useful information that may be difficult to obtain otherwise, such as finding opportunities to become involved in politics. At the same time, the frequent participation of individuals – in both online and offline groups – helps build trust among members, thus increasing the social media potential to stimulate commitment in protests, as well as other political behaviours (Kobayashi, Ikeda and Miyata, 2006). Social media are effective platforms for social interaction. Whether as an instance for chatting, connecting with family, friends and society, or accessing content of other people, social media can create the conditions that instill in youth an interest for collective public affairs. In addition, social media allow people to find others with similar ideas (Fábrega and Paredes, 2013) and, eventually, to organise activities with them. At the same time, through these sites people can access alternative news sources and increase their levels of social capital (Ellison et al., 2014; Valenzuela, Park and Kee, 2009). Finally, people noninterested in politics can engage with public affairs due to a casual or incidental exposure to social media (Xenos, Vromen and Loader, 2014, p. 154). The connection between social media use and protests has been shown in several international studies. In fact, the social mobilisations and democratisation in the Arab world in 2011, known as the ‘Arab Spring’, has intensified research on the relationship between social media and participation. Tufekci and Wilson (2012) found that the use of social media (mainly Facebook) had increased the likelihood of Egyptians attending the protests at Tahir Square against the Hosni Mubarak regime. Likewise, Lim (2012) explains how social media helped to articulate opposition movements to the government even before demonstrations began in 2011. In this context, social media emerge as resources to develop collective experiences – a necessary condition for the success of social movements and protests. As Bennett (2008) suggests, with their condition as ‘digital natives’,1 young people can experiment with new ways of exercising citizenship that aspire to achieving collective experiences associated with the use and appropriation of social media. For this reason, the first hypothesis of this article sets forth that: © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(5) SOCIAL MEDIA AND PROTESTS IN CHILE. 155. H1.1: There is a positive relationship between Facebook and the participation of Chilean youth in protest demonstrations. H1.2: There is a positive relationship between Twitter and the participation of Chilean youth in protest demonstrations. The relationship proposed in the first part of the hypothesis implies that users of this social media are more inclined to protest because they become involved in activities that are essential for collective action such as processing useful information, exchanging and forming opinions on public affairs, and building a common identity with their peers. This means that having a Facebook account or frequent media use increases the probability of performing these activities, but does not mechanically facilitate the action of protesting. Because Facebook and Twitter are different platforms, it is advisable to analyse their influence on protest participation separately. For one thing, the demographic profile of users is different. In Chile, Facebook has always been more popular among youth than Twitter (see Figures 3 and 4). The socioeconomic profile of users varies across network sites: whereas Facebook users are similarly distributed among the rich, middle and poor classes, Twitter users tend to come disproportionately from higher income groups (School of Journalism Universidad Diego Portales & Feedback, 2011). Moreover, the types of networks tapped by Facebook and Twitter are different, too. Facebook tends to be a symmetric network because both parties, or ‘friends’, must approve their Facebook relationship (Valenzuela, Arriagada and Scherman, 2014). Thus, Facebook ‘friendships’ tend to occur among people with an existing, offline relationship, which explains the benefits of Facebook for maintaining existing social ties (Ellison, Steinfield and Lampe, 2007). In contrast, Twitter networks are rather asymmetrical: users can have a relationship without both agreeing to it. Although Twitter users can protect their accounts by asking for permission to approve potential followers, compared to Facebook it is safe to assume that Twitter is more open to weak-tie relationships. Considering the differences in the social ties promoted by Facebook and Twitter, it is not surprising that both sites differ considerably in the type of content that is shared by users. Whereas Facebook users mostly share material related to their private and social spheres (e.g. family events, personal pictures, and videos), Twitter users frequently post and discuss news, current events and politics (School of Journalism Universidad Diego Portales & Feedback, 2011).. Postmaterialism and ideology In addition to describing the nature of the relationship between Facebook use and protesting – and the mechanisms through which this relationship exists – it is important to analyse the conditions that may regulate the role of online social relationships. There are reasons to believe that political and cultural values of individuals can expand or diminish the role played by social media. ‘Materialist values’ refer to security and survival goals that can be attained by material means, such as economic growth and maintaining public order. ‘Postmaterialist values’, in turn, emphasise autonomy and quality-of-life aspects, prioritising goals such as self-expression and achieving gender equality. They are postmaterialist in the sense that they do not refer to material or economic conditions per se. In his seminal The Silent Revolution, Inglehart (1977) © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(6) 156. ANDRÉS SCHERMAN, ARTURO ARRIAGADA AND SEBASTIÁN VALENZUELA. developed and tested two propositions regarding the development of these values. The scarcity hypothesis states that people’s goals are shaped by their socioeconomic environment so that the greatest value is placed on aspects of life that are in relatively short supply. It implies that wealth promotes postmaterialist values, whereas economic decline promotes materialist values. This relationship, however, is qualified by the socialisation hypothesis, which posits that the effect of the socioeconomic environment on goal priorities is not immediate, but takes place over the long run. Thus, most values develop before reaching adulthood and change relatively little thereafter (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005). In the case of Chile, a period of high economic growth and relative prosperity has coincided with the diffusion of postmaterialist values among young people.2 Not surprisingly, this process has been characterised by a tendency for youth to opt for direct political action (e.g. street demonstrations) instead of participating through conventional channels such as voting. At the same time, the participative and open nature of the internet and social media is coherent with a spirit of disrespect for traditional forms of authority – typical of postmaterialism – among those who use them for protesting and political mobilisation. Different studies have shown that the existence of postmaterialist values is associated with online media use (Davis and Owen, 1998; Theocharis, 2010). The question is whether postmaterialist values contribute to the emergence of online extra-institutional forms of political participation. In his study of the political participation of young people in Greece, Theocharis (2010, p. 215) found ‘postmaterialism is a weak predictor of online extrainstitutional activities’. For these reasons, we think that the interaction between posmaterialist values and social media influences political participation – albeit values are one of myriad possible mechanisms. In addition to postmaterialist values, an individual’s ideology may broaden the relationship between the use of social media and protesting. In general, people at the left of the ideological spectrum are more likely to participate in protests as part of their repertoire of political actions (Dalton, Sickle and Weldon, 2009). In Chile, issues such as public education and the environment are ‘owned’ (Petrocik, 1996) by progressive social movements and left-wing political parties. However, it must be said that postmaterialist values and the issues related to left-wing groups overlap each other. Hence, individuals with left-wing ideas may foster the relationship between Facebook and Twitter use and elite-challenging activities such as protesting. In sum: H2: The existing relationship between the use of social media and protesting is moderated by individuals’ political and cultural values. Specifically, the relationship between the use of Facebook and Twitter and the action of protesting is stronger in individuals that identify with postmaterialist values. Social capital is another dimension worthy of consideration. For Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992, p. 14), social capital is ‘the sum of the resources, actual or virtual, that accrue to an individual or a group by virtue of possessing a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition’. In the same direction, Lin (2001) equated social capital to an ‘investment in social relations’, which highlights the importance of personal relationships (Ellison, Steinfield and Lampe, 2007). Prior research has shown that social capital has a positive relationship with political participation in various ways. Through social capital, civil society can become strengthened and the social coordination of individuals is facilitated – both of which can result in higher levels of participation (Gil de Zúñiga, Jung and Valenzuela, 2012; Putnam, 2000; Valenzuela, Park and Kee, 2009). © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(7) SOCIAL MEDIA AND PROTESTS IN CHILE. 157. Interest in politics and political trust, are important determinants of participation, too. Interest in politics is an important predictor of political participation (Mannarini, Legittimo and Talò, 2008). Moreover, trust in political authorities has a controversial effect on political participation. Some authors say that trust in authorities increases participation overall (Fennema and Tillie, 1999; Sharoni, 2012), whereas others posit that trust increases conventional political participation only, but that mistrust triggers extra-institutional forms of participation, such as protests. Furthermore, when mistrust is accompanied by the perception of having a great capacity to influence public policy decisions, unconventional participation is particularly likely (Gamson, 1968; Johnson, Kaye and Kim, 2010; Mannarini, Legittimo and Talò, 2008). Although we do not posit specific hypotheses about the interaction between social media use, social capital, political interest and trust, we take into account these factors as control variables in the statistical models.. Method To test the hypotheses, we rely on data from the Youth, Participation and Media Consumption Survey of 2011, which contains detailed measures of protest participation, social media use and other sociodemographic variables. This survey interviewed 1,737 individuals aged 18 and older, living in Chile’s three largest urban centres (Greater Santiago, Greater Valparaíso and Greater Concepción), which comprise nearly two-thirds of the country’s adult population. The sample was probabilistic and queried using a face-to-face questionnaire. For the regression analyses, only young adults (in the 18–29 age group) were selected (N = 1,014). For more details on the survey, see Valenzuela, Arriagada & Scherman (2012). In order to test the hypotheses, regression models were built to explain two dependant variables: participation in the student movement (measured through an index with a minimum and maximum value of 0 and 4,3 respectively), which accounts for the type of activities carried out by the people in relation to this issue); and participation in the movement that opposed the HidroAysén construction (also considered through the construction of a counter, with minimum and maximum values of 0 and 3, respectively).4 There are five groups of explanatory variables: (1) use of online and traditional mass media (consumption hours of broadcast television, radio, press and online media); (2) presence on social media (registered with a Facebook and Twitter account); (3) postmaterialist values and ideology; (4) political and social variables previously identified as determinant of political participation (trust in institutions, social capital, political effectiveness, interest in politics); and (5) sociodemographic variables (gender, age and socioeconomic level).. Results Descriptive results Of the 1,014 respondents, 50.4 per cent were men, their mean age was 23.5 (standard deviation (S.D.): 3.6) and socioeconomic status was distributed in the following manner: 6.4 per cent ABC1 (upper class), 24 per cent C2 (upper middle class), 48 per cent C3 (lower middle class) and 21.8 per cent D–E (low class). In the realm of participation, the mean of activities linked with the student protests was 1.3 (S.D.: 0.9) measured through an index between 0 and 4, and the actions linked with environmental protests was 0.9 (S.D.: 0.8) measured through an index between 0 and 3. © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

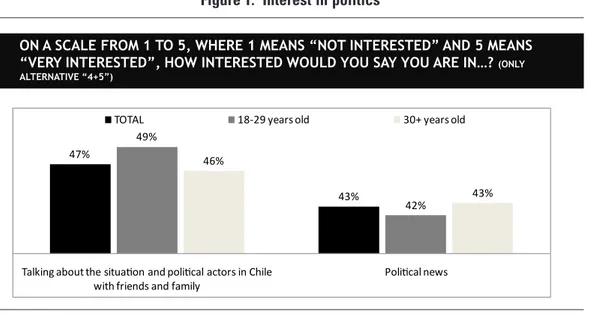

(8) 158. ANDRÉS SCHERMAN, ARTURO ARRIAGADA AND SEBASTIÁN VALENZUELA. Another relevant finding revealed that even though young people have voted with much less frequency than the rest of the population over the last two decades, the level of declared interest in politics for the 18–29 age group is not less than that of older individuals. In other words, despite an obvious lack of electoral participation among youth, this does not mean a lesser connection of youth with the debate on issues of public interest, or, as we recently analysed, in their wish to demonstrate publicly (see Figures 1 and 2). As Figures 1 and 2 show, interest in politics displayed by young people is very similar to that of the rest of the population. In fact, their political participation through non-electoral channels exceeds that of adults on several occasions. The survey also showed the extensive use of social media among Chilean youth. Facebook, without a doubt, leads the pack: 86 per cent of the population between 18 and 29 stated they were registered on this platform and 52 per cent logged on at least once a day. Twitter occupies a distant second place: 21 per cent declared having an active account and 14 per cent logged on every day. Likewise, the frequency in use of these social media in the 18–29 year old segment is significantly higher than in the adult population. While 86 per cent of youth have a Facebook account, only 39 per cent of the 30 + age group are in the same situation and, in the case of Twitter, the percentage of youth registered on this network is triple that of adults (see Figures 3 and 4). The relationship between youth participation in public affairs and the use of social media can be analysed in two important conflicts that marked the debate agenda in Chile in 2011: student demonstrations and first-semester protests against the HidroAysén power plant. Figure 1: Interest in politics ON A SCALE FROM 1 TO 5, WHERE 1 MEANS “NOT INTERESTED” AND 5 MEANS “VERY INTERESTED”, HOW INTERESTED WOULD YOU SAY YOU ARE IN…? (ONLY ALTERNATIVE “4+5”). TOTAL 49% 47%. 18-29 years old. 30+ years old. 46% 43%. Talking about the situaƟon and poliƟcal actors in Chile with friends and family. 43% 42%. PoliƟcal news. Source: Youth, Participation and Media Consumption 2011 Survey. © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(9) SOCIAL MEDIA AND PROTESTS IN CHILE. 159. Figure 2: Non-electoral participation. IN THE LAST TWELVE MONTHS, HAVE YOU…? (ONLY FOR AFFIRMATIVE ANSWERS). TOTAL. 18-29 AÑOS. 30+ AÑOS. 32%. 16%. 14% 10%. 10%. ParƟcipated in public protests and gatherings?. 13% 9%. Signed a ciƟzen peƟƟon addresses to a public authority?. 8%. 6%. AƩend a forum or debate on poliƟcal issues or public interest?. 7%. Figure 3: Registered on Facebook. DO YOU HAVE A FACEBOOK ACCOUNT?. 30 years +. 14%. 39% 61%. 86%. YES NO Source: Youth, Participation and Media Consumption 2011 Survey.. © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2). 7%. ParƟciping in a meeƟng with authoriƟes?. Source: Youth, Participation and Media Consumption 2011 Survey.. 18-29 years. 7%. YES NO.

(10) 160. ANDRÉS SCHERMAN, ARTURO ARRIAGADA AND SEBASTIÁN VALENZUELA. Figure 4: Registered on Twitter. DO YOU HAVE A TWITTER ACCOUNT?. 30 years +. 18-29 years. 7% 21% 79%. 93% YES YES NO. NO. Source: Youth, Participation and Media Consumption 2011 Survey.. project. Both conflicts were covered in depth in the 2011 survey, placing special emphasis on the ways in which people were informed and/or participated in each event. In terms of participation, social media played a relevant role in both conflicts as a medium through which a significant number of young people expressed their opinion or helped communicate information on the issue. For example, in the case of HidroAysén, communicating or exchanging news on the project was the second most frequent form in which youth related to the debate and was only exceeded by interpersonal conversations. Even communicating messages on social media and incorporating into groups created within them was much more widespread than traditional forms of participation such as street demonstrations, meetings with authorities, approaching political parties or attempting to contact traditional mass media (see Figure 5). In generational terms, there is also an obvious difference in the intensity with which youth use social media to become involved in this type of debate in comparison with the rest of the population. To cite just one example, while 42 per cent of young people exchanged information on the HidroAysén project through social media, only 14 per cent of those older than 30 did the same. In the case of student demonstrations, the role of social media as a form of youth participation was also important and it constituted the most frequent form of involvement in this debate after interpersonal conversations (see Figure 6). More than enabling new forms of participation, social media have also become a source of relevant information on issues of public interest, especially for youth. This situation became apparent on asking for the principal form in which people informed themselves on the HidroAysén project. Internet news sites and social media surpassed radio and newspapers in the ranking of the most important information sources in the 18–29 age group. In any case, © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(11) © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2). 55%. 14%. Communicate or exchange informaƟon on social networks?. 22%. 42%. 11%. Join a group of Facebook?. 18%. 35%. 7% 5%. 5%. 3%. 4%. 3%. 2%. 4%. 30+ years old. 1%. Contribute money Contact Join poliƟcal party to promote the tradicƟonal mass or group? project? media?. 5%. 18-29 years old. AƩend a public demonstraƟon?. 11%. 22%. Source: Youth, Participation and Media Consumption 2011 Survey.. Talk about the issue with other people?. 60%. 74%. TOTAL. THOSE WHO ANSWERED AFFIRMATIVELY; BASE: ONLY THOSE WHO HAVE HEARD OF THE PROJECT; N=1.505). WITH REGARD TO THE DEBATE ON THE HIDROAYSÉN PROJECT, DID YOU…?. Figure 5: Forms of participating in the Hidroaysén debate. 1%. 1%. Contact and authority?. 1%. (ONLY FOR. SOCIAL MEDIA AND PROTESTS IN CHILE 161.

(12) 80%. 67%. 22%. 45%. 14% 12%. AƩend a public protest?. 18%. 33%. 9%. Join a group in Facebook?. 17%. 39%. 9%. 15% 7%. 18-29 years old. Contribute a money to promote a project?. Source: Youth, Participation and Media Consumption 2011 Survey.. Talk about the issue Communicate with other people? informaƟon on social network?. 71%. TOTAL. 8%. 3% Join a local organizaƟon?. 4%. 2% 3% 1%. 1% 1% 1% Contact tradiƟonal Join a poliƟcal party Contact an authority? mass media? or group?. 3% 5% 2%. 30+ years old. WITH REGARD TO THE STUDENT CONFLICT, DID YOU…? (ONLY FOR THOSE WHO ANSWERED AFFIRMATIVELY; BASE: ONLY THOSE WHO HAVE HEARD OF THE PROJECT; N=1.721). Figure 6: Form of participating in the debate on student conflict. 162 ANDRÉS SCHERMAN, ARTURO ARRIAGADA AND SEBASTIÁN VALENZUELA. © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(13) SOCIAL MEDIA AND PROTESTS IN CHILE. 163. we must highlight that in spite of this difference with some of the traditional mass media (radio and press), digital platforms are still far behind television, which continues to dominate the information diet of Chileans of all ages (see Figure 7).. Testing of hypotheses The results of the regression analysis (see Table 1) substantiate our first hypothesis: having a Facebook account and being registered on Twitter are variables that are related to a higher participation in the student movement and protests against the construction of HidroAysén. This reaffirms the mobilising potential that social media can exert, even on a segment of the population that has overwhelmingly shown its distance from traditional political institutions (mainly parliamentarians and political parties) and electoral participation. In comparison to online social network use, traditional mass media news consumption shows a low association with the analysed forms of participation. News consumption from broadcast television and the press does not have a significant impact on the forms of participation associated with the student movement, and in the case of demonstrations against HidroAysén, the impact of exposure to broadcast television news is negative. Meanwhile, radio shows a positive relation with the possibility of getting involved in the student movement, but the impact is relatively limited. On the other hand, the use of online mass media for information (news sites and blogs) does show a positive impact on the two movements under analysis, accounting for a clear contrast with traditional mass media. In line with the theory of ‘changing values’, the presence of postmaterialist values and the ideological position also appear linked with participation in both movements. Young people with postmaterialist values5 (i.e. when able to choose, they privilege freedom of expression or greater participation in political decisions over alternatives such as keeping law and order or a lower inflation rate) show a significantly higher link than the rest of their peers with non-electoral political participation, especially in the student movement. Likewise, those who identify with right-wing political views6 are less likely to become involved in this type of participation. Along with variables linked to the use of social media and mass media, it is relevant to analyse the weight of other factors that have been approached by literature specialised in political participation. Social capital, measured in terms of the respondents’ participation in different types of social organisations, shows an important impact. In fact, not belonging to any type of social organisation diminishes the probability of a youth becoming involved in the student movement or demonstrations against HidroAysén. Other highly relevant variables are political interest and institutional trust. The former is a strong predictor of participation while the latter has a negative effect, meaning that the people who took part in the two forms of protests we are measuring did so because of strong mistrust of institutions (particularly political institutions). Indeed, this mistrust was precisely one of the factors that led them to demonstrate. On analysing the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents, the incidence of the socioeconomic level is remarkable: belonging to a high-income group (ABC1) is positively related to having participated in the protest movements, which does not hold true for any other socioeconomic segment. This reflects that the participation of higher-income segments © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(14) 63%. 77%. 16% 5%. News website on Internet. 8%. TOTAL. 11% 5%. Social networks. 7%. Source: Youth, Participation and Media Consumption 2011 Survey.. Television. 73%. PROJECT; N=1.505). 5%. Radio. 3%. 6%. 18-29 years old. 3%. 3% Print newspapers. 3%. 2%. 2% Family, friends or acquaintances. 2%. 30+ years old. 0%. 1% Print magazines. 1%. WHAT IS THE MAIN MASS MEDIA YOU HAVE USED TO OBTAIN INFORMATION ON THE DEBATE ON THE HIDROAYSÉN PROJECT? (BASE: ONLY THOSE WHO HAVE HEARD OF THE. Figure 7: Media used to be informed on Hidroaysén project. 164 ANDRÉS SCHERMAN, ARTURO ARRIAGADA AND SEBASTIÁN VALENZUELA. © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(15) SOCIAL MEDIA AND PROTESTS IN CHILE. 165. Table 1: Poisson regressions for predicting participation in the student movement and opposition to the Hidroaysén project. Gender (Female) Male SEG (D–E) (low class) ABC1 (upper class) C2 (upper middle class) C3 (lower middle) Age Values (Materialism) Mixed Postmaterialism Trust in other people (No) Yes Trust in institutions Political effectiveness Political interest Associativity (Participates) Does not participate in organisations Political position (left-right) Hours of broadcast TV news Hours of radio news Hours of press news Hours of online media news Registered on Facebook (No) Yes Registered on Twitter (No) Yes N Deviation (Value/gl). Student movement (B). Opposition to Hidroaysén (B). −0.068. 0.004. 0.293* 0.165 0.032 −0.046**. 0.227* 0.121 0.017 −0.003. 0.134 0.415**. 0.055 0.150*. 0.121 −0.194** 0.008 0.130**. 0.293** −0.213** 0.003 0.138**. −0.303** −0.079** −0.012 0.046* 0.020 0.033*. −0.205** −0.037** −0.020* −0.002 0.004 0.040*. 0.221*. 0.173*. 0.180* 704 0.663. 0.186* 704 0.392. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.. in these movements was greater than that of the rest of the population, even though, in principle, these protests sought to benefit the poorest sectors of society, as is the case of the petitions made by the student movement. Finally, analysis of the interaction between the presence of postmaterialist values and social network use (see Table 2) did not provide enough evidence to substantiate our second hypothesis that the use of social media and protesting is moderated by people’s social and political values. Although the use of social media and the presence of postmaterialist values © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(16) 166. ANDRÉS SCHERMAN, ARTURO ARRIAGADA AND SEBASTIÁN VALENZUELA. Table 2: Poisson regressions to predict participation in student movement and actions in opposition to the Hidroaysén project (including interaction effects). Gender (Female) Male SEG (D–E) (low class) ABC1 (upper class) C2 (upper middle class) C3 (lower middle) Age Values (Materialism) Mixed Postmaterialism Trust in other people (No) Yes Trust in institutions Political effectiveness Political interest Associativity (Participates) Does not participate in organisations Political position (left-right) Hours of broadcast TV news Hours of radio news Hours of press news Hours of online media news Registered on Facebook (No) Yes Registered on Twitter (No) Yes Interactions Facebook x Postmaterialist values Twitter x Postmaterialist values N Deviation. Student movement (B). Opposition to Hidroaysén (B). −0.063. 0.003. 0.315** 0.182** 0.037 −0.046** 0.138 −0.146. 0.220* 0.113 0.017 −0.003 0.053 0.293. 0.123 −0.205** 0.004 0.133**. 0.240** −0.213** 0.005 0.137**. 0.309** −0.079** −0.012 0.043* 0.020 0.031*. 0.202** −0.036** −0.020 −0.003 0.004 0.040**. 0.110. 0.210*. 0.132. 0.162*. 0.566* 0.148 704 0.659. −0.185 0.089 704 0.392. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.. are significant predictors of participation (as independent variables), it does not hold true when the interaction between both is analysed. Only in the case of participation in the student movement does the joint presence of postmaterialist values and being registered on Facebook show a significant impact – a finding that was not repeated on establishing the determinant factors of the protests against HidroAysén or on studying the interaction between postmaterialist values and the use of Twitter. © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(17) SOCIAL MEDIA AND PROTESTS IN CHILE. 167. We can think of two reasons that may explain why H2 was not supported. From a methodological perspective, there may be a problem with measurement error. In this research, postmaterialism was gauged with Inglehart’s (1997) classic four-item index, which has been found to be less reliable than the more extensive 12-item measure proposed later by the same author (Inglehart, 1990). As is well known, measurement error can significantly attenuate correlation. From a theoretical perspective, the scant work available that has tested the interaction between values and using digital media has also not been able to establish a strong relationship between postmaterialism and online political participation (e.g. Theocharis, 2010, p. 215).. Conclusion This article has analysed the relationship between the use of social media and youth protests in Chile on issues of education and the environment. According to the analyses presented, we conclude that there is a positive relationship between the use of both Facebook and Twitter and participation in student demonstrations and street marches against the construction of a power plant in the Patagonia. Controlling for ideology, political interest, social capital and traditional media, people with an active account in these online media are more likely to protest. It is relevant to note that this study deals two different movements – student and environmental – formed by individuals with different characteristics and goals that use social media intensively to influence the public debate. This phenomenon could be indicative of a more general change in the way young people are protesting, where social media are becoming more important in coordination and motivation for participation in social movements. Nevertheless, the greater role of social media does not remove the importance of demonstrations outside the online world. Although it is not possible to separate the offline and online spheres, the lower costs for accessing information and resources to coordinate actions with social media reinforce the attendance to public protests. Offline and online actions are complementary forms of participation – not competitive ones. It is also important to note that social media have a stronger association with public participation than do traditional media. The results show that newspaper reading is not related to the participation in the movements under study. They also demonstrate that the exposure to broadcast television news has a small negative relationship and, finally, exposure to radio news increases slightly the possibility of protesting. In summary, this investigation shows that for urban youth in Chile, the association between social media and participation is more relevant than traditional sources of information. This result is consistent with prior research not only in Chile, but elsewhere (Valenzuela, 2013; Valenzuela, Arriagada and Scherman, 2012; White and McAllister, 2014; Xenos and Moy, 2007). As a consequence, it is likely that new protest cycles will confirm the power of social media over other media in mobilising youth. The relationship between social media and public participation notwithstanding, it should be emphasised that traditional variables related to citizen participation – ideology, political interest and social capital – are important factors associated with the involvement in the student and environmental movements and should always be considered in analyses that involve public participation. In this sense, following the idea of the ‘virtuous circle’ (Norris, 2000), social media probably reinforce and strengthen previous interests in public affairs, © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(18) 168. ANDRÉS SCHERMAN, ARTURO ARRIAGADA AND SEBASTIÁN VALENZUELA. increasing the possibility of participation. The influence of media is not mechanical; it is part of a more complex process that involves multiple variables. Regarding the hypothesis that tested the interaction between postmaterialist values and social media use on participation, the data presented do not allow us to confirm that the use of social media is moderated by people’s political and cultural values. Bearing in mind that Facebook and Twitter use and ascribing postmaterialist values are predictors of participation in protests, the interaction between values and social media use only has a positive relationship in the case of the student movement and not in the case of the HidroAysén protests. Despite the fact that the interaction between values and social media use shows a weak association with participation in protests, it is important to analyse the strong relationship between postmaterialist values and participation (see Table 1). Young people that ascribe to postmaterialist values – linked to self-expression and quality of life – are more likely to participate in social movements. This result is consistent with the strong economic growth of Chilean economy in the last 25 years, allowing the transition from materialist to postmaterialist values in Chilean society (Scherman and Arriagada, 2012). Although the use of these digital platforms reduces the costs of organising and spreading the petitions of those protesting in the public sphere, the socioeconomic differences observed among the users of these online digital media is alarming. This inequality of information and technological capital may minimise the political repertoire of similar citizens or that have not yet incorporated the use of Facebook or Twitter into exercising their citizenship. The cross-sectional characteristic of our data limits the possibility of establishing causal relationships; however language was used carefully to not imply causal effects. Also, due to the usage of survey data, the self-report about participation and media use may be affected by social desirability bias. The usage of panel data would allow the establishment of causal relationships with more confidence. Regarding the case studies, the types of participation analysed in both cases (if the person joined organisations linked to the student movement, if they participated in public demonstrations, if they donated money and if they spoke about the subject with other people) are oriented towards legal changes or another type of reaction by the government or the state. There are open questions regarding the relationship between protest and the use of social media when the counterpart is a private company. Bennett (2004) suggests that there are less institutionalised forms of protest – labeled ‘lifestyle politics’ – where political communication and demands ‘adopt a lifestyle vocabulary anchored in consumer choice, self-image, and personal displays of social responsibility’ (Bennett, 2004, p. 102). This form of protest (e.g. boycotting) can involve actors with various motivations and forms of expressions that are organised in similar or different ways by actors using social media platforms. Future research should explore further the relationship between people’s cultural values and use of social media. Given that we found a weak, but positive, interaction between these two variables for the student movement, it is possible that we may find this phenomenon in other situations. Similarly, there is a black-box that needs to be opened regarding the types of networking and engagement formed through uses of social media that evolve into protest. Finally, a qualitative inquiry on social media use for protest behaviour and political participation should be conducted. © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(19) SOCIAL MEDIA AND PROTESTS IN CHILE. 169. Acknowledgments The authors are grateful to Teresa Correa, who contributed with important comments that enriched this article. Also, we are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their feedback and contributions.. Notes 1 This concept refers to managing the technical knowhow to use digital technology. Having grown up in the digital era, youth are more exposed to the use and appropriation of these digital technologies. This leads to the development of skills and knowledge in order to use technology such as online social media. 2 In the period 1986–2011, the Chilean economy had an average growth of 5.4 per cent. In the same period, the population in poverty fell from 38.6 per cent (1990) to 15.1 per cent (2009). Meanwhile, the per capita gross domestic product (PPT) increased from US$3,350 (1986) to US$15,800 (2011). 3 In order to construct this counter, four factors linked to the student movement are considered: if the person joined organisations linked to the student movement; if they participated in public demonstrations; if they donated money; and if they spoke about the subject with other people. People who did not perform any of these activities received the minimum value of 0, while those who did all of them received the maximum value of 4. 4 With the same logic of the previous indicator, three factors linked to the opposition to Hidroaysén were considered: participation in public demonstrations; making money donations; and talking about the subject with others. 5 For this work, the postmaterialism index with four items proposed by Ronald Inglehart was used and the respondents were classified as mixed or materialist postmaterialists. 6 This variable was measured on a scale from 1 to 10 in which the respondents were asked to place themselves, with 1 representing the left and 10 the right.. References Bakker, T.P. and De Vreese, C.H. (2011) ‘Good News for the Future? Young People, Internet Use and Political Participation’, Communication Research 38, pp. 451–470. Bennett, W.L. (2004) ‘Branded Political Communication: Lifestyle Politics, Logo Campaigns and the Rise of Global Citizenship’ in M. Micheletti, A. Follesdal and D. Stolle (eds.), The Politics behind Products, New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, pp. 101–126. Bennett, W.L. (2008) ‘Changing Citizenship in the Digital Age’ in W.L. Bennett (ed.), Civic Life Online: Learning How Digital Media Can Engage Youth, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 1–24. Bennett, W.L. and Segerberg, A. (2012) ‘The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics’, Information, Communication and Society 15, pp. 739–768. Bimber, B. (2001) ‘Information and Political Engagement in America: The Search for Effects of Information Technology at the Individual Level’, Political Research Quarterly 54, pp. 53–67. Bimber, B. (2003) Information and American Democracy, New York: Cambridge University Press. Boulianne, S. (2009) ‘Does Internet Use Affect Engagement? A Meta-Analysis of Research’, Political Communication 26, pp. 193–211. Bourdieu, P. and Wacquant, L. (1992) An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Dalton, R.J. (2008) ‘Citizenship Norms and the Expansion of Political Participation’, Political Studies 56, pp. 76–98. Dalton, R.J., Sickle, A. and Weldon, S. (2009) ‘The Individual-Institutional Nexus of Protest Behaviour’, British Journal of Political Science 40, pp. 51–73. Davis, R. and Owen, D. (1998) New Media and American Politics, New York: Oxford University Press. Ekström, M. and Östman, J. (2013) ‘Family Talk, Peer Talk and Young’s People Civic Orientation’, European Journal of Communication 28, pp. 294–308. Ellison, N.B., Steinfield, C. and Lampe, C. (2007) ‘The Benefits of Facebook “Friends”: Social Capital and College Students’ Use of Online Social Network Sites’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12, pp. 1143–1168. Ellison, N.B., Vitak, J., Gray, R. and Lampe, C. (2014) ‘Cultivating Social Resources on Social Network Sites: Facebook Relationship Maintenance Behaviors and Their Role in Social Capital Processes’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19(4), pp. 855–870. Ellison, N.B. and Boyd, D. (2013) ‘Sociality through Social Network Sites’ in W.H. Dutton (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Internet Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 151–172. Fábrega, J. and Paredes, P. (2013) ‘La Política Chilena en 140 Caracteres’ in A. Arriagada and P. Navia (eds.), Intermedios, Medios de Comunicación y Democracia en Chile, Santiago: Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales, pp. 199–223. © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(20) 170. ANDRÉS SCHERMAN, ARTURO ARRIAGADA AND SEBASTIÁN VALENZUELA. Fennema, M. and Tillie, J. (1999) ‘Political Participation and Political Trust in Amsterdam: Civic Communities and Ethnic Networks’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 25, pp. 703–726. Gamson, W.A. (1968) Power and Discontent, Homewood, IL: Dorsey. Gil de Zúñiga, H. and Valenzuela, S. (2011) ‘The Mediating Path to a Stronger Citizenship: Online and Offline Networks, Weak Ties and Civic Engagement’, Communication Research 38, pp. 397–421. Gil de Zúñiga, H., Jung, N. and Valenzuela, S. (2012) ‘Social Media Use for News and Individuals’ Social Capital, Civic Engagement and Political Participation’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 17, pp. 319–336. Hargittai, E. (2007) ‘Whose Space? Differences among Users and Non-Users of Social Network Sites’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13, pp. 276–297. Harlow, S. (2012) ‘Social Media and Social Movements: Facebook and an Online Guatemalan Justice Movement That Moved Offline’, New Media and Society 14, pp. 225–243. Howard, P. and Parks, M. (2012) ‘Social Media and Political Change: Capacity, Constraint and Consequence’, Journal of Communication 62, pp. 359–362. Inglehart, R. (1977) The Silent Revolution, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Inglehart, R. (1990) Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Inglehart, R. (1997) Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic and Political Change in 43 Societies, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Inglehart, R. and Welzel, C. (2005) Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence, New York: Cambridge University Press. Johnson, T.J., Kaye, B.K. and Kim, D. (2010) ‘Creating a Web of Trust and Change: Testing the Gamson Hypothesis on Politically Interested Internet Users’, Atlantic Journal of Communication 18, pp. 259–279. Kobayashi, T., Ikeda, K.I. and Miyata, K. (2006) ‘Social Capital Online: Collective Use of the Internet and Reciprocity as Lubricants of Democracy’, Information, Communication and Society 9, pp. 582–611. Kwak, N., Shah, D.V. and Holbert, R.L. (2004) ‘Connecting, Trusting and Participating: The Interactive Effects of Social Associations and Generalized Trust on Collective Action’, Political Research Quarterly 57, pp. 643–652. Lim, M. (2012) ‘Clicks, Cabs and Coffee Houses: Social Media and Oppositional Movements in Egypt, 2004–2011’, Journal of Communication 62, pp. 231–248. Lin, N. (2001) Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Mannarini, T., Legittimo, M. and Talò, C. (2008) ‘Determinants of Social and Political Participation among Youth: A Preliminary Study’, Psicología Política 36, pp. 95–117. Nie, N.H. (2001) ‘Sociability, Interpersonal Relations and the Internet: Reconciling Conflicting Findings’, American Behavioral Scientist 45, pp. 420–435. Norris, P. (2000) A Virtuous Circle: Political Communications in Post-Industrial Democracies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Owen, D. (2008) ‘Election Media and Youth Political Engagement’, Journal of Social Science Education 78, pp. 14–25. Petrocik, J.R. (1996) ‘Issue Ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980 Case Study’, American Journal of Political Science 40, pp. 825–850. Putnam, R. (2000) Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of the American Community, New York: Simon & Schuster. Raynes-Goldie, K. and Walker, L. (2008) ‘Our Space: Online Civic Engagement Tools for Youth’ in W.L. Bennett (ed.), Civic Life Online: Learning How Digital Media Can Engage Youth, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 161–188. Rheingold, H. (2000) Tools for Thought: The History and Future of Mind-Expanding Technology, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Scherman, A. and Arriagada, A. (2012) ‘Jóvenes, Postmaterialismo y Consumo en Medios’ in A. Scherman (ed.), Jóvenes, Participación y Medios, Santiago: Universidad Diego Portales, pp. 8–17. School of Journalism Universidad Diego Portales & Feedback (2011) Third Survey on Youth, Participation and Media Consumption [Data file]. Available from: http://www.cip.udp.cl/encuesta-jovenes-y-participacion-periodismo-udpfeedback-2011 [Accessed 6 August 2014]. Shah, D.V., Kwak, N. and Holbert, R.L. (2001) ‘ “Connecting” and “Disconnecting” with Civic Life: Patterns of Internet Use and the Production of Social Capital’, Political Communication 18, pp. 141–162. Sharoni, S. (2012) ‘E-Citizenship: Trust in Government, Political Efficacy and Political Participation in the Internet Era’, Electronic Media and Politics 1(8), pp. 119–135. Theocharis, J. (2010) ‘Young People, Political Participation and Online Postmaterialism in Greece’, New Media and Society 13, pp. 203–223. © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(21) SOCIAL MEDIA AND PROTESTS IN CHILE. 171. Tufekci, Z. and Wilson, C. (2012) ‘Social Media and the Decision to Participate in Political Protest: Observations from Tahrir Square’, Journal of Communication 62, pp. 363–379. Valenzuela, S. (2013) ‘Unpacking the Use of Social Media for Protest Behavior: The Roles of Information, Opinion Expression and Activism’, American Behavioral Scientist 57, pp. 920–942. Valenzuela, S., Arriagada, A. and Scherman, A. (2012) ‘The Social Media Basis of Youth Protest Behaviour: The Case of Chile’, Journal of Communication 62, pp. 299–314. Valenzuela, S., Arriagada, A. and Scherman, A. (2014) ‘A Longitudinal Study of Social Media and Youth Protest: Facebook, Twitter and Student Mobilization in Chile (2010–2012)’, International Journal of Communication 8, pp. 2046–2070. Valenzuela, S., Park, N. and Kee, K.F. (2009) ‘Is There Social Capital in a Social Network Site? Facebook Use and College Students’ Life Satisfaction, Trust and Participation’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14, pp. 875–901. Vitak, J., Zube, P., Smock, A., Carr, C., Ellison, N. and Lampe, C. (2011) ‘It’s Complicated: Facebook Users’ Political Participation in the 2008 Election’, Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking 14(3), pp. 107–114. White, S. and McAllister, I. (2014) ‘Did Russia (Nearly) Have a Facebook Revolution in 2011? Social Media’s Challenge to Authoritarianism’, Politics 34, pp. 72–84. Xenos, M. and Moy, P. (2007) ‘Direct and Differential Effects of the Internet on Political and Civic Engagement’, Journal of Communication 57, pp. 704–718. Xenos, M., Vromen, A. and Loader, B. (2014) ‘The Great Equalizer? Patterns of Social Media Use and Youth Political Engagement in Three Advances Democracies’, Information, Communication and Society 17, pp. 151–167.. About the authors Andrés Scherman (MA, Universidad Católica de Chile) is Associate Professor in the School of Communications at Diego Portales University, where he is also Director of the International Master in Communication. His research focuses on political participation, political communication, social media and youth. Andrés Scherman, School of Communications, Universidad Diego Portales, Vergara 240, Santiago, Chile. E-mail: andres.scherman@udp.cl. Twitter: @aschermant Arturo Arriagada (PhD, London School of Economics and Political Science) is Assistant Professor in the School of Communications and Adjunct Professor in the School of Sociology at Diego Portales University. His research topics are the relation between culture and digital technologies, political communication and social media. Arturo Arriagada, School of Communications, Universidad Diego Portales, Vergara 240, Santiago, Chile. E-mail: arturo.arriagada@udp.cl. Twitter: @arturoarriagada Sebastián Valenzuela (PhD, University of Texas at Austin) is Assistant Professor in the School of Communications at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and Associate Researcher at the National Research Centre for Integrated Natural Disaster Management (CIGIDEN). He specialises in political communication, social media and public opinion research. His work is supported in part by CONICYT (Chile) via Fondap no. 15110017. Sebastián Valenzuela, School of Communications, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Alameda 340, Santiago, Chile. E-mail: savalenz@uc.cl. Twitter: @SebaValenz. © 2014 The Authors. Politics © 2014 Political Studies Association POLITICS: 2015 VOL 35(2).

(22)

Figure

Documento similar

Predictive models built from variations of the random forest algorithm were used in this research to estimate the mechanical properties of steel coils in order to classify them

Even though the 1920s offered new employment opportunities in industries previously closed to women, often the women who took these jobs found themselves exploited.. No matter

After the Spanish withdrawal from the territory in 1975, Morocco waged a brutal military campaign against the Polisario, and large numbers of people fled to refugee camps, where

Doyle, 2010; Kjus, 2009; Bardoel, 2007). Two forms of participation coexist in the public media: 1) an official and structural type of participation, linked to the

Based on this information schools were advised to organise groups of teachers (and in the two professional development schools to include in the group also student teachers)

With this in mind the two scattering models are now used to calculate the particle’s effective radius with respect to time; first the measured refractive index is squared in order

In order to estimate and forecast the volatility of stock index return in Amman Stock Exchange (ASE) market, four different ARCH-type models will be used, two models for testing the

In the preparation of this report, the Venice Commission has relied on the comments of its rapporteurs; its recently adopted Report on Respect for Democracy, Human Rights and the Rule