Fibra, estructura y actividad enzimática relacionada con su degradación

Texto completo

(2) Por este medio otorgo mi AVAL al Trabajo De Grado Titulado: “FIBRA, ESTRUCTURA Y ACTIVIDAD ENZIMÁTICA RELACIONADA CON SU DEGRADACIÓN” Del estudiante: ERIKA ALEJANDRA SOTO CHARRY Ya que cumple los requisitos mínimos para la sustentación del título de Médico Veterinario Zootecnista. Dado en la ciudad de Ibagué Tolima, Colombia. María del Roció Pérez Rubio Asesora. 1 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(3) Tabla de contenido Agradecimientos.....................................................................................................................6 Resumen.................................................................................................................................7 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................8 1.. Introducción ..................................................................................................................9. 2.. Justificación ................................................................................................................ 10. 3.. Objetivos .................................................................................................................... 11. 4.. 3.1.. General ................................................................................................................ 11. 3.2.. Específicos........................................................................................................... 11. Metodología ................................................................................................................ 12 4.1.1.. 5.. Caracterización de la literatura revisada ............................................................... 12. Fibra ........................................................................................................................... 64 5.1.. Estructura de la Fibra Vegetal .............................................................................. 64. 5.1.1.. Celulosa ............................................................................................................... 66. 5.1.2.. Hemicelulosa ....................................................................................................... 67. 5.1.3.. Lignina ........................................................................................................................... 68. 5.2. La Función De La Pared Celular Y La Unión Estructural De La Celulosa, Hemicelulosa Y Lignina ........................................................................................................ 70 5.3.. Mecanismos Enzimáticos en la Degradación de la Fibra....................................... 73. 5.3.1.. Degradación de la Celulosa ............................................................................................. 75. 5.3.2.. Degradación de la Hemicelulosa ..................................................................................... 78. 5.3.3.. Degradación de la Lignina .............................................................................................. 82. 6.. Conclusiones ............................................................................................................... 89. 7.. Bibliografía ................................................................................................................. 90. 2 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(4) Listado de Tablas. Tabla 1. Muestra de los autores identificados y su país de origen. ........................................ 63 Tabla 2. Enzimas, bacterias y hongos importantes en la degradación de la hemicelulosa ..... 79. 3 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

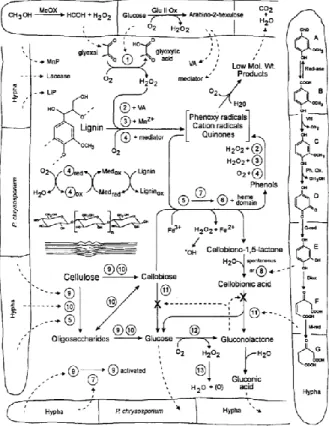

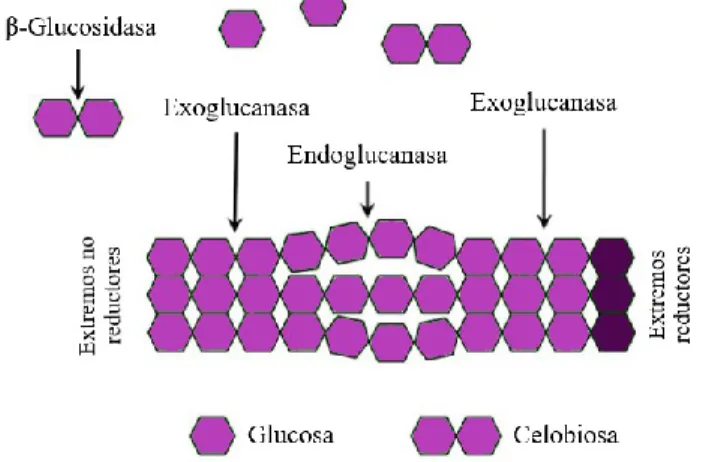

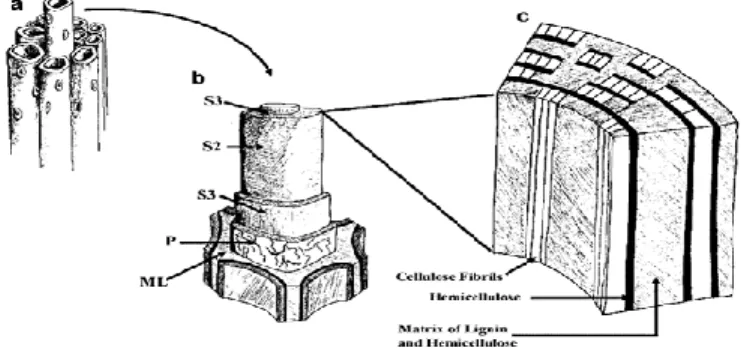

(5) Listado de Figuras. Figura 1. A – C. Configuración de tejidos de madera. .......................................................... 65 Figura 2. Estructura de la celulosa lineal β-D-glucopiranosil-β-1,4-D-glucopiranosa. .......... 67 Figura 3. Estructurasde: (A) xiloglucano, (B) Xilano, (C) Glucomananos - galactomananos, y (D) Glucomananos de madera blanda. ....................................................................................... 68 Figura 4. Unidades de fenilpropano encontradas en monolignoles según su estructura. ........ 69 Figura 5. (A) La estructura de la lignina se biosintetiza mediante una reacción de acoplamiento de radicales libres; (B) Elemento estructural clave en el proceso de polimerización por radicales libres. ................................................................................................................... 70 Figura 6. Estructura de la pared primaria y los enlaces entrecruzados. ................................. 72 Figura 7. Representación estructural de la pared secundaria de la célula. ............................. 73 Figura 8. Mecanismos enzimáticos extra e intracelulares implicados en la degradación de la lignina y la celulosa por el hongo de la pudrición blanca Phanerochaete chrysosporium. ........... 75 Figura 9. Sistemas enzimáticos implicados en la degradación de la celulosa. ....................... 76 Figura 10. Principales actividades de las enzimas celulósicas y una ruta para la formación de soforosa por la transglicosilación de b-glucosidasa. ................................................................... 77 Figura 11. Mecanismos enzimáticos para la regulación extracelular del Sporotrichum pulverulentum en la degradación de la celulosa. ........................................................................ 78 Figura 12. Degradación del sistema hemicelulolítico de arabinoxilano. ................................ 80 Figura 13. Estructura de xilano y los sitios de ataque por enzimas xilanolíticas. ................... 81 Figura 14. Estructura de (A) 1,3-β-glucano lineal no ramificado (B) 1,3;1,4-β-glucano lineal de enlaces mixtos y (C) 1,3;1,6-β-glucano ramificado. .............................................................. 81. 4 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(6) Figura 15. Actividades enzimáticas en la despolimerización de arabinoxilano. .................... 82 Figura 16. La interacción compleja de reacciones enzimáticas y no enzimáticas en la degradación de la lignina por hongos......................................................................................... 83 Figura 17. La lignina peroxidasa y su estructura de hierro. ................................................... 84 Figura 18. Ciclo catalítico de la lignina peroxidasa de lignina (LiP). .................................... 85 Figura 19. Peroxidasa de manganeso y su degradación. ....................................................... 85 Figura 20. Ciclo catalítico de peroxidasa de manganeso (Mn), peróxido de hidrogeno (H2O2), Agua (H2O). ............................................................................................................... 86 Figura 21. Estructura de la lacasa y su degradación. ............................................................. 87 Figura 22. Mecanismo de reducción y oxidación de los sitios de cobre enzimático. ............. 88. 5 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(7) Agradecimientos. En primera instancia, gracias a Dios, por las bendiciones que día a día le brinda a mí ser, incluyendo la oportunidad de poder compartir al lado de las personas que amo. Gracias a mis padres, por ser quienes han formado la persona que soy, gracias a ellos por confiar en mis capacidades, apoyar este gran sueño y enseñarme que no sólo el crecimiento cognoscitivo es importante, sino que hay algo más valioso: el crecimiento personal. Gracias a la Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia por haberme enriquecido de un conocimiento valioso para mi futuro y gracias a todas aquellas personas que hicieron parte dentro de este proceso aportando parte de su valioso tiempo, en especial, a la doctora María del Roció Pérez Rubio, quien, sin sus orientaciones y su paciencia, la culminación del presente proyecto no se hubiera efectuado.. 6 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(8) Resumen. La fibra se encuentra en las plantas y forma sus paredes celulares que se dividen en primaria y secundaria, a su vez compuestas de celulosa, hemicelulosa y lignina en diferentes proporciones, dependiendo del estado fenológico de la planta y su clasificación vegetal. La celulosa es un biopolímero renovable el cual se encuentra en todo el planeta, no es tóxica y es biodegradable; se degrada por la acción de las celulasas como endoglucanasas, exoglucanasas y β-glucosidasas. La hemicelulosa es un heteropolisacárido compuesto de azúcares tales como xiloglucanos, glucamanano y xilanos; es degradado por la acción de xilanasas y glucanasas. Por último, la lignina, que no es plisacarido y compuesta por tres tipos de unidades a saber: cumaril, guaiacil, y siringil; su degradación depende del ciclo catalítico de enzimas como lignina peroxidasa, manganeso peroxidasa, lacasa y fenol oxidasa. En conjunto, este arsenal de enzimas participa en la degradación de la fibra y son fundamentales en el ciclo de carbono en la naturaleza y confiere a las poblaciones microbianas su capacidad degradadora de la biomasa vegetal. El objetivo de esta revisión es ofrecer de manera sintetica información valida respecto a la estructura de la fibra y la actividad enzimática relacionada con su degradación.. Palabras Claves: polímeros, Li peroxidasa, endoglucanasa, biodregradación, xilanasa, polifenol.. 7 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(9) Abstract. Fiber is found in plants and forms its cell walls that are divided into primary and secondary, in turn composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in different proportions, depending on the phenological state of the plant and its plant classification. Cellulose is a renewable biopolymer found all over the planet, is non-toxic and biodegradable; is degraded by the action of cellulase esthetics,. as. endoglucanases,. exoglucanases. and. glucosidase.. Hemicellulose. is. a. heteropolysaccharide composed of sugars such as xyloglucans, glucomannan, and xylans; is degraded by the action of xylanases and glucanases. Finally, lignin, which is not polysaccharide and composed of three types of units namely: coumarin, guaiacil, and syringil; its degradation depends on the catalytic cycle of enzymes such as lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, Lacasse, and phenoloxidase. Together, this arsenal of enzymes is involved in fiber degradation and is fundamental in the carbon cycle in nature and gives microbial populations their degrading capacity of plant biomass. The objective of this review is to provide synthetically valid information regarding the structure of the fiber and the enzymatic activity related to its degradation. Keywords: polymers, Li peroxidase, endoglucanase, biodegradation, xylanases, a polyphenol. 8 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(10) 1. Introducción. El desarrollo de las plantas conjuga factores ambientales y genéticos. Estímulos como temperatura, luminosidad, humedad, CO2, nutrientes disponibles son críticos desde la germinación hasta el desarrollo de las plantas (Jiang , Wang, Aluru , & Dong, 2019). La fibra de las plantas es hidrofilia; sin embargo, esta característica puede generar espacios vacíos en la interfaz fibra-matriz celular, que ocasionan en su interior tensiones entre sus componentes por la presencia de gomas ricas en pectina y la lignina que une las fibras y la goma afecta la dispersión individual de las fibras (Bousfield , Morin , Jacquet, & Richel , 2018, págs. 897–906). La actividad microbiana participa en la biodegradación de la fibra y su actividad se expresa en la tasa de descomposición y se correlaciona con la tasa de mineralización de la hemicelulosa y la lignina que se incorpora al suelo como materia orgánica exógena (Vandecasteele, y otros, 2018, págs. 43–54 ). Por otra parte, la matriz actúa como un medio de transferencia de carga entre las fibras, y en casos menos ideales donde las cargas son complejas, la matriz puede proteger las fibras del daño ambiental (Elanchezhian, y otros, 2018, págs. 1785–90).. 9 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(11) 2. Justificación. Para la alimentación animal se emplean recursos vegetales, cuya digestibilidad se ve afectada por el contenido de fibra, esta ultima brinda protección a los vegetales y les confiere rigidez a sus células y en la medida que las plantas adquieren madurez aumenta su contenido y en consecuencia afecta negativamente su digestibilidad. Los nutricionistas deben considerar este componente al momento de formular las reciones para animales, en especial en formulaciones para monogástricos dado que no cuentan con las enzimas endógenas para su digestión. La fibra esta conformada principalmente por los polisicaridos celulosa y hemicelulosa, además de la lignina, esta ultima, un polifenol que le dá una estructura recalcitrante a la pared fibrosa, y dificulta el acceso a los polisacáridos que rodea. Para comprender los procesos de degradación de la fibra, es necesario conocer su estructura y la actividad enzimática relacionada con su degradación, así como la forma en que estas enzimas actúan, dada su relevante importancia por su participación en el ciclo del carbono en la naturaleza, y en donde los microorganismos juegan un papel protagónico ya que las poblaciones microbianas poseen la capacidad degradadora de la biomasa vegetal que se incorpora en los suelos como materia orgánica.. 10 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(12) 3. Objetivos. 3.1.General Conceptualizar la estructura de la fibra y la actividad enzimática relacionada con su degradación.. 3.2.Específicos. 3.2.1. Conceptualizar la función de la pared celular y la unión estructural de la celulosa, hemicelulosa y lignina. 3.2.2. Describir los sistemas enzimáticos implicados en la degradación de la celulosa, hemicelulosa y lignina.. 11 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(13) 4. Metodología. Se utilizará una revisión sistemática en artículos científicos y revistas indexadas; como técnica exploratoria para la recolección de información sobre fibra, estructura y actividad enzimática relacionada con su degradación. Mediante una técnica comparativa se analizará y sintetizará la información más importante para la realización de un análisis sistemático de revisión literaria y concluir respecto a este tópico. 4.1. Análisis crítico y consideraciones a los resultados 4.1.1. Caracterización de la literatura revisada En la revisión sistemática de la literatura de 156 estudios realizados. Las publicaciones consultadas, fueron hechas entre el año 1957 y 2019. No. 1. Autor(es) Jiang, H. Wang, X.. País USA. Referencia Jiang, H. Wang, X. Aluru, MR. & Dong,. Aluru, MR. & Dong,. L. (2019). Plant Miniature Greenhouse.. L.. Sensors Actuators A Phys. [Internet]. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0924424719310088. 2. Bousfield, G. Morin,. Bélgica. Bousfield, G. Morin, S. Jacquet, N. &. S. Jacquet, N. &. Richel A. (2018). Extraction and. Richel A.. refinement of agricultural plant fibers for composites manufacturing. Comptes Rendus Chim [Internet]. 21(9):897–906.. 12 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(14) Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S1631074818301735 3. Vandecasteele, B.. Bélgica. Vandecasteele, B. Muylle, H. De Windt,. Muylle, H. De Windt,. I. Van Acker, J. Ameloot, N. Moreaux,. I. Van Acker, J.. K. et al. (2018). Plant fibers for. Ameloot, N. Moreaux,. renewable growing media: Potential of. K. et al.. defibration, acidification or inoculation with biocontrol fungi to reduce the N drawdown and plant pathogens. J Clean Prod [Internet]. 203:1143–54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08. 167. 4. Elanchezhian, C.. India. .Elanchezhian, C. Ramnath, BV.. Ramnath, BV.. Ramakrishnan, G. Rajendrakumar, M.. Ramakrishnan, G.. Naveenkumar, V. & Saravanakumar,. Rajendrakumar, M.. MK. (2018). Review on mechanical. Naveenkumar, V. &. properties of natural fiber composites.. Saravanakumar, MK.. Mater Today Proc [Internet]. 5(1):1785– 90. Available from : https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2017.11.2 76. 13 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(15) 5. Somerville, C. Bauer,. USA. Somerville, C. Bauer, S. Brininstool, G.. S. Brininstool, G.. Facette, M. Hamann, T. Milne, J. et al.(. Facette, M. Hamann,. 2004). Toward a Systems Approach to. T. Milne, J. et al.. Understanding Plant Cell Walls. Science (80- ) [Internet]. 306(5705):2206–11. Available from: http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/doi/10.11 26/science.1102765. 6. Burton, RA. Gidley,. Australia. MJ. & Fincher GB.. Burton, RA. Gidley, MJ. & Fincher GB. (2010). Heterogeneity in the chemistry, structure and function of plant cell walls. Nat Chem Biol [Internet]. 6(10):724–32. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.439. 7. Zhao Q, Dixon RA.. USA. Zhao Q, Dixon RA. (2011). Transcriptional networks for lignin biosynthesis: more complex than we thought? Trends Plant Sci [Internet]. 16(4):227–33. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2010.1 2.005. 14 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(16) 8. Martínez, M, Rincón,. España. Martínez, M, Rincón, F. Periago, M.. F. Periago, M. Ros, G. Ros, G & López, G. (1993) Componentes. & López, G. de la fibra dietética y sus efectos fisiológicos. Rev española Cienc y Tecnol Aliment [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 6];33(3):229–46. Available from: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo? codigo=717095. 9. Potty, H.. India. Potty, H. (1996). Physio-chemical [physico-chemical] aspects, physiological functions, nutritional importance and technological significance of dietary fibres: A critical appraisial. J Food Sci Technol [Internet]. ;33(1):1–18. Available from: https://scholar.google.com.co/scholar?clu ster=184092325595127363&hl=es&oi=s cholarr. 10. Savon, L. Cuba. Savon, L. (2002). Alimentos altos en fibra para especies monogástricas. Caracterización de la matriz fibrosa y sus efectos en la fisiología digestiva. Rev Cuba Cienc Agrícola. 36(2):91–102.. 15 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(17) 11. Templeton, W.. USA. Templeton, W. Sluiter, D. Hayward, K.. Sluiter, D. Hayward,. Hames, R. & Thomas, R. (2009).. K. Hames, R. &. Assessing corn stover composition and. Thomas, R.. sources of variability via NIRS. Cellulose [Internet]. 16(4):621–39. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10570009-9325-x. 12. Cosgrove, J.. USA. Cosgrove, J. (2005). Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol [Internet]. 6(11):850–61. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/nrm1746. 13. Zamil, S. &. Canadá. Geitmann, A.. Zamil, S. & Geitmann, A.( 2017). The middle lamella—more than a glue. Phys Biol [Internet]. 16;14(1):015004. Available from: http://stacks.iop.org/14783975/14/i=1/a=015004?key=crossref.e1b 5efc10429d540224706ce2a9bc0e3. 14. Geitmann A.. Canadá. Geitmann A. (2010). Mechanical modeling and structural analysis of the primary plant cell wall. Curr Opin Plant Biol [Internet]. 13(6):693–9. Available. 16 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(18) from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2010.09.0 17 15. Monniaux, M. & Hay A. Monniaux, M. & Hay A. (2016). Cells, Alemania. walls, and endless forms. Curr Opin Plant Biol [Internet]. 34:114–21. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2016.10.0 10. 16. Zhao, Y. Man, Y.. China. Zhao, Y. Man, Y. Wen, J. Guo, Y. & Lin,. Wen, J. Guo, Y. &. J. (2019). Advances in Imaging Plant. Lin, J.. Cell Walls. Trends Plant Sci [Internet]. 1–12. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2019.05. 009. 17. Prinsen, P.. España. Prinsen, P. (2010). Composición química de diversos materiales lignocelulósicos de interés industrial [Internet]. Universidad de Sevilla. Available from: http://www.irnase.csic.es/users/delrio/rep ository theses/2010-Prinsen-MsC.pdf. 17 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(19) 18. Pettolino, A. Walsh,. Australia. Pettolino, A. Walsh, C. Fincher, B. &. C. Fincher, B. &. Bacic, A. (2012). Determining the. Bacic, A.. polysaccharide composition of plant cell walls. Nat Protoc [Internet]. 7(9):1590– 607. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2012.081. 19. Kirk, K. & Cullen, D.. USA. Kirk, K. & Cullen, D. (1998). Enzymology and molecular genetics of wood degradation by white-rot fungi. Environmentally friendly technologies for the pulp and paper industry. p. 273– 307.. 20. Treviño,J. &. España. Arosemena, G.. Treviño,J. & Arosemena, G. (1971). Determinación de la fracción fibra de los forrajes. Pastos Rev la Soc Española para el Estud los Pastos. 1(1):120–5.. 21. McCahill, W. & Hazen, P.. USA. McCahill, W. & Hazen, P. (2019). Regulation of Cell Wall Thickening by a Medley of Mechanisms. Trends Plant Sci [Internet]. p. 1–14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2019.05. 012. 18 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(20) 22. Fernández, I. &. España. Gonzalez, D.. Fernández, I. & Gonzalez, D. (2011). Polisacáricos No Amiláceos Y Complejos Multienzimáticos; como mejorar el valor nutricional dl pienso. Sel AVÍCOLAS [Internet]. p.19–22. Available from: https://seleccionesavicolas.com/pdffiles/2011/10/6309-polisacaridos-noamilaceos-y-complejosmultienzimaticos-como-mejorar-el-valornutricional-del-pienso.pdf. 23. Alba, D.. Colombia. Alba, D. (2013). Efectos nutricionales de los polisacáridos no amiláceos en pollo de engorde de la línea Ross. Rev Cienc y Agric [Internet]. 10(1):39–45. Available from: http://revistas.uptc.edu.co/revistas/index. php/ciencia_agricultura/article/view/2826 /2594. 24. Mateos, G. Lázaro, R.. España. Mateos, G. Lázaro, R. González, J.. González, J. Jiménez,. Jiménez, E. & Vicente, B. (2006).. E. & Vicente, B.. Efectos De La Fibra Dietética En Piensos De Iniciación Para Pollitos Y Lechones. 19 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(21) [Internet]. XXII Curso de Especialización FEDNA. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Available from: http://www.produccionbovina.com.ar/pro duccion_porcina/00produccion_porcina_general/54fibra_piensos_iniciacion.pdf 25. Chandra, R. & Rustgi,. India. R.. Chandra, R. & Rustgi, R. (1998). Biodegradable polymers. Prog Polym Sci [Internet]. 23(7):1273–335. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0079670097000397. 26. Klemm, D. Heublein,. Alemania. Klemm, D. Heublein, B. Fink, P. &. B. Fink, P. & Bohn,. Bohn, A. (2005). Cellulose: Fascinating. A.. Biopolymer and Sustainable Raw Material. Angew Chemie Int Ed [Internet]. 44(22):3358–93. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/anie.20046 0587. 27. Heinze, T.. Alemania. Heinze, T. (2015). Cellulose: Structure and Properties. In: Advanced Computer. 20 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(22) Simulation Approaches For Soft Matter Sciences I [Internet]. p. 1–52. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/12_2015 _319 28. Campbell, N. Smith,. Reino Unido. D. & Peters, J.. Campbell, N. Smith, D. & Peters, J. (2010). Bioquímica ilustrada : bioquímica y biología molecular en la era posgenómica. 5a ed. Barcelona: Elsevier Masson.. 29. Gopi , S.. India. Gopi , S. Balakrishnan, P. Chandradhara,. Balakrishnan, P.. D. Poovathankandy, D. & Thomas, S.. Chandradhara, D.. (2019). General scenarios of cellulose. Poovathankandy, D.. and its use in the biomedical field. Mater. & Thomas, S.. Today Chem [Internet]. 13:59–78. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S2468519419300072. 30. Montoya, B.. Colombia. Montoya, B. (2008). Actividad enzimática, degradación de residuos sólidos orgánicos y generación de biomasa útil del macromiceto grifola frondosa [Internet]. Universidad Nacional. 21 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(23) de Colombia sede Manizales. Available from: http://www.bdigital.unal.edu.co/956/1/sa ndramontoyabarreto.2008.pdf 31. Lee, H. Brown, M.. USA. Lee, H. Brown, M. Kuga, S. Shoda, S. &. Kuga, S. Shoda, S. &. Kobayashi, S.(1994). Assembly of. Kobayashi, S. synthetic cellulose I. Proc Natl Acad Sci. [Internet].1(16):7425–9. Available from: http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pna s.91.16.7425. 32. Yang, T.. USA. Yang, T. (2007). Bioprocessing – from Biotechnology to Biorefinery. In: Bioprocessing for Value-Added Products from Renewable Resources. [Internet]. Elsevier;. p. 1–24. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/B9780444521149500025. 33. Pérez, J. Muñoz, J. De. España. Pérez, J. Muñoz, J. De la Rubia, T. &. la Rubia, T. &. Martínez, J. (2002). Biodegradation and. Martínez, J.. biological treatments of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin: an overview. Int Microbiol [Internet]. 5(2):53–63. Available from:. 22 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(24) http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10123002-0062-3 34. Rodríguez, P. García,. España.. J. & De Blas, C.. Rodríguez, P. García, J. & De Blas, C. (1930). Fibra Soluble Y Su Implicación En Nutrición Animal: Enzimas Y Probióticos. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.. 35. Scheller, V. Ulvskov,. USA. P.. Scheller, V. Ulvskov, P. (2010). Hemicelluloses. Annu Rev Plant Biol [Internet]. 61(1):263–89. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.114 6/annurev-arplant-042809-112315. 36. Jeffries, W.. USA. Jeffries, W. (1994). Biodegradation of lignin and hemicelluloses. In: Biochemistry of microbial degradation [Internet]. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. p. 233–77. Available from: http://www.springerlink.com/index/10.10 07/978-94-011-1687-9_8. 37. Dekker, H.. Nueva York. Dekker, H. (1985). Biodegradation of the Hemicellulose. In: biosynthesis and biodegradation of wood component. New York: Academic Press. p. 505–32.. 23 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(25) 38. Hatfield, R.. USA. Vermerris, W.. Hatfield, R. Vermerris, W. (2001). Lignin Formation in Plants. The Dilemma of Linkage Specificity. Plant Physiol [Internet]. 126(4):1351–7. Available from: http://www.plantphysiol.org/lookup/doi/1 0.1104/pp.126.4.1351. 39. Quintana, J.. Colombia. Quintana, J. (2012). Pretratamiento con agua líquida caliente de raquis de banano. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.. 40. Huang, J. Fu, S. &. China. Gan, L.. Huang, J. Fu, S. & Gan, L. (2019). Structure and Characteristics of Lignin. In: Lignin Chemistry and Applications [Internet]. Elsevier. p. 25–50. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/B9780128139417000023. 41. McCarthy, J.. Suecia. McCarthy, J. (1957). Introduction - The Lignin Problem. Ind Eng Chem [Internet]. 49(9):1377–1377. Available from: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ie505 73a030. 24 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(26) 42. Adler, E.. Suecia. Adler, E. (1977). Lignin chemistry - past, present and future. Wood Sci Technol [Internet]. 11(3):169–218. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF0036 5615. 43. Dalimova, N. &. Suiza. Abduazimov, A. Dalimova, N. & Abduazimov, A. (1994). Lignins of herbaceous plants. Chem Nat Compd [Internet]. 30(2):146–59. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF0062 9995. 44. Meister, J.. Francia. Meister, J. (2019). Chemical Modification of Lignin. In: Lignin Chemistry and Applications [Internet]. Elsevier. p. 51–78. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/B9780128139417000035. 45. Bommarius, S. Riebel, R.. Alemania. Bommarius, S. Riebel, R. (2005). Applications of Enzymes as Bulk Actives: Detergents, Textiles, Pulp and Paper, Animal Feed. In: Biocatalysis [Internet]. Weinheim, FRG: Wiley-VCH. 25 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(27) Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. p. 135–58. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/352760236 4.ch6 46. Brett, T. Keith, W.. Países Bajos. Brett, T. Keith, W. (1990). Physiology and Biochemistry of Plant Cell Walls [Internet]. 2nd ed. London: Springer Netherlands. 194 p. Available from: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/97804 12720208. 47. Rose, K.. USA. Rose, K. (2003). The plant cell wall. [Internet]. Vol. 1, Annals of Botany. Ithaca: Blackwell;.p. 1–144. Available from: https://meynyeng.files.wordpress.com/20 10/12/the-plant-cell-wall.pdf. 48. Evert, F.. USA. Evert, F. (2006). Esau’s Plant Anatomy. In: Esau’s Plant Anatomy [Internet]. Tbird. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. p. 567–601. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0025540803003210. 26 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(28) 49. Bidlack, J. Jansky, S.. USA. & Stern, K.. Bidlack, J. Jansky, S. & Stern, K. (2018). Stern’s Introductory Plant Biology. 14th ed. McGraw-Hill, editor. McGraw-Hill Publishing Company.. 50. Albersheim, P.. USA. Albersheim, P. (1975). The Walls of Growing Plant Cells. Sci Am [Internet]. 232(4):80–95. Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038 /scientificamerican0475-80. 51. Goodwin TW, Mercer. USA. W. Goodwin TW, Mercer W. Introduction to Plant Biochemistry. 2nd ed. Pergamon, editor. New York; 1990. 660 p.. 52. Keegstra K, Talmadge. USA. Keegstra K, Talmadge KW, Bauer WD,. KW, Bauer WD,. Albersheim P. The Structure of Plant Cell. Albersheim P.. Walls. Plant Physiol [Internet]. 1973 Jan 1;51(1):188–97. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16 658282%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.n ih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC3673 77. 53. Preston RD.. Reino Unido. Preston RD. Polysaccharide Conformation and Cell Wall Function. Annu Rev Plant Physiol [Internet]. 1979. 27 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(29) Jun;30(1):55–78. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.114 6/annurev.pp.30.060179.000415 54. Fry SC.. Reino Unido. Fry SC. Cross-Linking of Matrix Polymers in the Growing Cell Walls of Angiosperms. Annu Rev Plant Physiol [Internet]. 1986 Jun;37(1):165–86. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.114 6/annurev.pp.37.060186.001121. 55. Esau K.. USA. Esau K. Anatomy of Seed Plants. 2nd ed. John Wiley, Sons, editors. New York; 1977. 576 p.. 56. Giddings TH, Brower DL, Staehelin LA. Inglaterra. Giddings TH, Brower DL, Staehelin LA. Visualization of particle complexes in the plasma membrane of Micrasterias denticulata associated with the formation of cellulose fibrils in primary and secondary cell walls. J Cell Biol [Internet]. 1980 Feb 1;84(2):327–39. Available from: http://www.jcb.org/cgi/doi/10.1083/jcb.8 4.2.327. 28 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(30) 57. Herth W.. Alemania. Herth W. Plasma-membrane rosettes involved in localized wall thickening during xylem vessel formation of Lepidium sativum L. Planta [Internet]. 1985;164(1):12–21. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF0039 1020. 58. Hatfield RD. USA. Hatfield RD. Structural Polysaccharides in Forages and Their Degradability. Agron J [Internet]. 1989;81(1):39. Available from: https://www.agronomy.org/publications/a j/abstracts/81/1/AJ0810010039. 59. Freudenberg K, Neish. Alemania. AC.. Freudenberg K, Neish AC. Constitution and Biosynthesis of Lignin [Internet]. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1968. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3642-85981-6. 60. Bidlack JE, Dashek W USA. Bidlack JE, Dashek W V. Plant cell. V.. walls. In: Plant Cells and their Organelles [Internet]. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016. p. 209–38. Available. 29 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(31) from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/B9780121233020500095 61. Carpita NC, Defernez. USA. Carpita NC, Defernez M, Findlay K,. M, Findlay K, Wells. Wells B, Shoue DA, Catchpole G, et al.. B, Shoue DA,. Cell wall architecture of the elongating. Catchpole G, et al.. maize coleoptile. Plant Physiol [Internet]. 2001 Oct 1;127(2):551–65. Available from: http://www.plantphysiol.org/lookup/doi/1 0.1104/pp.010146. 62. Albersheim P, Darvill. USA. Albersheim P, Darvill A, Roberts K,. A, Roberts K,. Sederoff R, Staehelin A. Plant cell walls.. Sederoff R, Staehelin. [Internet]. 1st ed. Garland Science, editor.. A.. Vol. 108, Annals of Botany. New York; 2010. 430 p. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/aob/articlelookup/doi/10.1093/aob/mcr128. 63. Hayashi T.. USA. Hayashi T. The Science and Lore of the Plant Cell Wall: Biosynthesis, Structure and Function. 1st ed. BrownWalker Press Boca Raton. Florida; 2006. 365 p.. 30 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(32) 64. Labavitch JM.. USA. Labavitch JM. Cell Wall Turnover in Plant Development. Annu Rev Plant Physiol [Internet]. 1981 Jun;32(1):385– 406. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.114 6/annurev.pp.32.060181.002125. 65. Huber DJ, Nevins DJ.. USA. Huber DJ, Nevins DJ. Partial purification of endo- and exo-B-D-glucanase enzymes from Zea mays L. seedlings and their involvement in cell-wall autohydrolysis. Planta [Internet]. 1981 Mar;151(3):206–14. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF0039 5171. 66. Hahlbrock K,. Alemania. Grisebach H.. Hahlbrock K, Grisebach H. Enzymic Controls in the Biosynthesis of Lignin and Flavonoids. Annu Rev Plant Physiol [Internet]. 1979 Jun;30(1):105–30. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.114 6/annurev.pp.30.060179.000541. 67. Lewis NG, Yamamoto USA. Lewis NG, Yamamoto E. Lignin:. E.. Occurrence, Biogenesis and. 31 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(33) Biodegradation. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol [Internet]. 1990 Jun;41(1):455–96. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.114 6/annurev.pp.41.060190.002323 68. Moore, K. & Jung, H.. USA. Moore, K. & Jung, H. Forage Lignins and Their Effects on Fiber Digestibility. Agron J [Internet]. 1989;81(1):33. Available from: https://www.agronomy.org/publications/a j/abstracts/81/1/AJ0810010033. 69. Cerda-Mejía L.. España. Cerda-Mejía L. Enzimas modificadoras de la pared celular vegetal,Celulasas de interés biotecnológico papelero [Internet]. Vol. 86, Carbohydrate Polymers. Barcelona; 2016. Available from: https://www.tesisenred.net/bitstream/han dle/10803/398119/LCM_TESIS.pdf?sequ ence=1&isAllowed=y. 70. Eriksson K-EL,. USA. Eriksson K-EL, Blanchette RA, Ander P.. Blanchette RA, Ander. Microbial and Enzymatic Degradation of. P.. Wood and Wood Components [Internet].. 32 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(34) Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1990. 691 p. (Springer Series in Wood Science; vol. 99). Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3642-46687-8 71. Bruchmann E, Schach. USA. H, Graf H.. Bruchmann E, Schach H, Graf H. Role and properties of lactonase in a cellulase system. Biotechnol Appl Biochem [Internet]. 1987;9:146–59. Available from: https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10010713076/. 72. Sasaki T, Tanaka T,. Japón. Sasaki T, Tanaka T, Nakagawa S,. Nakagawa S,. Kainuma K. Purification and properties. Kainuma K.. of Cellvibrio gilvus cellobiose phosphorylase. Biochem J [Internet]. 1983 Mar 1;209(3):803–7. Available from: http://www.biochemj.org/cgi/doi/10.1042 /bj2090803. 73. Ljungdahl LG, Eriksson K-E.. USA. Ljungdahl LG, Eriksson K-E. Ecology of Microbial Cellulose Degradation. In:. 33 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(35) Atlas RM, Jones JG, J0rgensen BB, editors. K. C. Mars. Australia: PLENUM PRESS• NEW YORK AND LONDON; 1985. p. 237–99. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-14615-9412-3_6 74. Biely P.. Eslovaquia.. Biely P. Microbial xylanolytic systems. Trends Biotechnol [Internet]. 1985 Nov;3(11):286–90. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/0167779985900046. 75. Poutanen K.. Finlandia. Poutanen K. Characterization of xylanolytic enzymes for potential applications [Internet]. 1988. Available from: https://cris.vtt.fi/en/publications/character ization-of-xylanolytic-enzymes-forpotential-application. 76. Ishihara T.. USA. Ishihara T. Lignin Biodegradation: Microbiology, Chemistry, and Potential Applications [Internet]. Kirk TK, Higuchi T, Chang H, editors. CRC Press; 1980. Available from:. 34 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(36) https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/978 1351082518 77. Leonowicz A, Szklarz. Polonia. Leonowicz A, Szklarz G, Wojtaś-. G, Wojtaś-. Wasilewska M. The effect of fungal. Wasilewska M.. laccase on fractionated lignosulphonates (peritan Na). Phytochemistry [Internet]. 1985;24(3):393–6. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0031942200807347. 78. Wariishi H, Dunford. USA. Wariishi H, Dunford HB, MacDonald ID,. HB, MacDonald ID,. Gold MH. Manganese peroxidase from. Gold MH.. the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Transient state kinetics and reaction mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(6):3335–40.. 79. Sterjiades R, Dean JD, USA. Sterjiades R, Dean JD, Gamble G,. Gamble G,. Himmelsbach D, Eriksson K-E.. Himmelsbach D,. Extracellular laccases and peroxidases. Eriksson K-E.. from sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) cell-suspension cultures. Planta [Internet]. 1993 May;190(1):75– 87. Available from:. 35 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(37) http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF0019 5678 80. Kelley RL, Reddy. USA. CA.. Kelley RL, Reddy CA. Purification and characterization of glucose oxidase from ligninolytic cultures of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Bacteriol [Internet]. 1986 Apr;166(1):269–74. Available from: http://jb.asm.org/lookup/doi/10.1128/jb.1 66.1.269-274.1986. 81. Eriksson K-E,. Alemania. Eriksson K-E, Pettersson B, Volc J,. Pettersson B, Volc J,. Musilek V. Formation and partial. Musilek V.. characterization of glucose-2-oxidase, a H2O2 producing enzyme in Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol [Internet]. 1986 Jan;23(3–4):257–62. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF0026 1925. 82. Kersten PJ, Kirk TK.. USA. Kersten PJ, Kirk TK. Involvement of a new enzyme, glyoxal oxidase, in extracellular H2O2 production by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J. 36 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(38) Bacteriol [Internet]. 1987 May;169(5):2195–201. Available from: http://jb.asm.org/lookup/doi/10.1128/jb.1 69.5.2195-2201.1987 83. Borneman WS,. USA. Borneman WS, Hartley RD, Morrison. Hartley RD, Morrison. WH, Akin DE, Ljungdahl LG. Feruloyl. WH, Akin DE,. and p-coumaroyl esterase from anaerobic. Ljungdahl LG.. fungi in relation to plant cell wall degradation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol [Internet]. 1990 Jun;33(3):345–51. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF0016 4534. 84. Borneman WS,. USA. Borneman WS, Ljungdahl LG, Hartley. Ljungdahl LG,. RD, Akin DE. Isolation and. Hartley RD, Akin DE.. characterization of p-coumaroyl esterase from the anaerobic fungus Neocallimastix strain MC-2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57(8):2337–44.. 85. Akin DE, Rigsby LL.. USA. Akin DE, Rigsby LL. Mixed fungal populations and lignocellulosic tissue degradation in the bovine rumen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53(9):1987–95.. 37 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(39) 86. Borneman S, Akin. USA. DE.. Borneman S, Akin DE. The nature of anaerobic fungi and their polysaccharide degrading enzymes. Mycoscience [Internet]. 1994 Jul;35(2):199–211. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S1340354094711281. 87. Kuhad RC, Singh A,. India. Eriksson K-EL.. Kuhad RC, Singh A, Eriksson K-EL. Microorganisms and enzymes involved in the degradation of plant fiber cell walls. In: Advances in biochemical engineering/biotechnology [Internet]. 1997. p. 45–125. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BFb010 2072. 88. Mandels M, Weber J.. India. Mandels M, Weber J. The Production of Cellulases. In: Hajny GJ, Reese ET, editors. Cellulases and Their Applications [Internet]. 1969. p. 391–414. Available from: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ba1969-0095.ch023. 38 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(40) 89. Kumar PKR, Singh A,. Alemania. Schugerl K.. Kumar PKR, Singh A, Schugerl K. Formation of acetic acid from cellulosic substrates byFusarium oxysporum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol [Internet]. 1991 Feb;34(5):570–2. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF0016 7900. 90. McHale A, Coughlan. Irlanda. MP.. McHale A, Coughlan MP. Synergistic hydrolysis of cellulose by components of the extracellular cellulase system of Talaromyces emersonii. FEBS Lett [Internet]. 1980 Aug 11;117(1–2):319– 22. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1016/00145793%2880%2980971-9. 91. Eriksson K-E, Wood TM.. USA. Eriksson K-E, Wood TM. Biodegradation of Cellulose. In: Biosynthesis and Biodegradation of Wood Components [Internet]. Elsevier; 1985. p. 469–503. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/B9780123478801500210. 39 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(41) 92. Tomme P, Warren. Canadá. RAJ, Gilkes NR.. Tomme P, Warren RAJ, Gilkes NR. Cellulose Hydrolysis by Bacteria and Fungi. In: Advances in Microbial Physiology [Internet]. 1995. p. 1–81. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0065291108601435. 93. Kataeva IA, Seidel. USA. Kataeva IA, Seidel RD, Shah A, West. RD, Shah A, West LT,. LT, Li X-L, Ljungdahl LG. The. Li X-L, Ljungdahl. Fibronectin Type 3-Like Repeat from the. LG.. Clostridium thermocellum Cellobiohydrolase CbhA Promotes Hydrolysis of Cellulose by Modifying Its Surface. Appl Environ Microbiol [Internet]. 2002 Sep 1;68(9):4292–300. Available from: http://aem.asm.org/cgi/doi/10.1128/AEM .68.9.4292-4300.2002. 94. Ratanakhanokchai K,. Tailandia,. Ratanakhanokchai K, Waeonukul R,. Waeonukul R, Pason. Japón.. Pason P, Tachaapaikoon C, Lay K, Sakka. P, Tachaapaikoon C,. K, et al. Paenibacillus curdlanolyticus. Lay K, Sakka K, et al.. Strain B-6 Multienzyme Complex: A Novel System for Biomass Utilization.. 40 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(42) In: Biomass Now - Cultivation and Utilization [Internet]. InTech; 2013. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/bioma ss-now-cultivation-andutilization/paenibacillus-curdlanolyticusstrain-b-6-multienzyme-complex-anovel-system-for-biomass-utilization 95. Teeri TT.. Suecia. Teeri TT. Crystalline cellulose degradation: new insight into the function of cellobiohydrolases. Trends Biotechnol [Internet]. 1997 May;15(5):160–7. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0167779997010329. 96. Moore D.. Inglaterra. Moore D. Fungal Morphogenesis [Internet]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. Available from: http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ref/id/CBO9 780511529887. 97. Yang Z, Liao Y, Fu X, USA. Yang Z, Liao Y, Fu X, Zaporski J, Peters. Zaporski J, Peters S,. S, Jamison M, et al. Temperature. Jamison M, et al.. sensitivity of mineral-enzyme. 41 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(43) interactions on the hydrolysis of cellobiose and indican by β-glucosidase. Sci Total Environ [Internet]. 2019 Oct;686:1194–201. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.0 5.479 98. Amarasekara AS,. USA. Amarasekara AS, Wiredu B, Lawrence. Wiredu B, Lawrence. YM. Hydrolysis and interactions of d-. YM.. cellobiose with polycarboxylic acids. Carbohydr Res [Internet]. 2019 Mar;475:34–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2019.02.0 02. 99. Aro N, Pakula T,. Finlandia. Penttilä M.. Aro N, Pakula T, Penttilä M. Transcriptional regulation of plant cell wall degradation by filamentous fungi. FEMS Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2005 Sep;29(4):719–39. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/femsre/articlelookup/doi/10.1016/j.femsre.2004.11.006. 100. Saloheimo M, Paloheimo M, Hakola. USA. Saloheimo M, Paloheimo M, Hakola S, Pere J, Swanson B, Nyyssönen E, et al. Swollenin, a Trichoderma reesei protein. 42 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(44) S, Pere J, Swanson B,. with sequence similarity to the plant. Nyyssönen E, et al.. expansins, exhibits disruption activity on cellulosic materials. Eur J Biochem [Internet]. 2002 Sep;269(17):4202–11. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1046/j.14321033.2002.03095.x. 101. Foreman PK, Brown. USA. Foreman PK, Brown D, Dankmeyer L,. D, Dankmeyer L,. Dean R, Diener S, Dunn-Coleman NS, et. Dean R, Diener S,. al. Transcriptional Regulation of. Dunn-Coleman NS, et. Biomass-degrading Enzymes in the. al.. Filamentous Fungus Trichoderma reesei. J Biol Chem [Internet]. 2003 Aug 22;278(34):31988–97. Available from: http://www.jbc.org/lookup/doi/10.1074/jb c.M304750200. 102. De Vries RP, Visser J.. Países Bajos. De Vries RP, Visser J. Aspergillus Enzymes Involved in Degradation of Plant Cell Wall Polysaccharides. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev [Internet]. 2001 Dec 1;65(4):497–522. Available from: http://mmbr.asm.org/cgi/doi/10.1128/M MBR.65.4.497-522.2001. 43 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(45) 103. Araki T, Kitamikado. Japón. M.. Araki T, Kitamikado M. Purification and Characterization of a Novel Exo-βMannanase from Aeromonas sp. F-25. J Biochem [Internet]. 1982 Apr;91(4):1181–6. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jb/articlelookup/doi/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbche m.a133801. 104. Dekker RFH,. Australia. Richards GN.. Dekker RFH, Richards GN. Hemicellulases: Their Occurrence, Purification, Properties, and Mode of Action. In 1976. p. 277–352. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S006523180860339X. 105. Špániková S, Biely P.. Eslovaquia. Špániková S, Biely P. Glucuronoyl esterase - Novel carbohydrate esterase produced by Schizophyllum commune. FEBS Lett [Internet]. 2006 Aug 21;580(19):4597–601. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1016/j.febslet.20 06.07.033. 44 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(46) 106. Topakas E, Moukouli. Grecia. Topakas E, Moukouli M, Dimarogona M,. M, Dimarogona M,. Vafiadi C, Christakopoulos P. Functional. Vafiadi C,. expression of a thermophilic glucuronoyl. Christakopoulos P.. esterase from Sporotrichum thermophile: identification of the nucleophilic serine. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol [Internet]. 2010 Aug 16;87(5):1765–72. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00253010-2655-7. 107. Javier PFI, Óscar G,. España. Javier PFI, Óscar G, Sanz-Aparicio J,. Sanz-Aparicio J, Díaz. Díaz P. Xylanases: Molecular Properties. P.. and Applications. In: Industrial Enzymes [Internet]. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2007. p. 65–82. Available from: http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url ?eid=2-s2.084892227353&partnerID=tZOtx3y1. 108. Planas A.. España. Planas A. Bacterial 1,3-1,4-β-glucanases: structure, function and protein engineering. Biochim Biophys Acta Protein Struct Mol Enzymol [Internet].. 45 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(47) 2000 Dec;1543(2):361–82. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0167483800002314 109. Gaiser OJ, Piotukh K,. Alemania. Gaiser OJ, Piotukh K, Ponnuswamy MN,. Ponnuswamy MN,. Planas A, Borriss R, Heinemann U.. Planas A, Borriss R,. Structural Basis for the Substrate. Heinemann U.. Specificity of a Bacillus 1,3-1,4-βGlucanase. J Mol Biol [Internet]. 2006 Apr;357(4):1211–25. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0167483800002314. 110. Vincken J-P, Beldman. Países Bajos. G, Voragen AGJ.. Vincken J-P, Beldman G, Voragen AGJ. Substrate specificity of endoglucanases: what determines xyloglucanase activity? Carbohydr Res [Internet]. 1997 Mar;298(4):299–310. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0008621596003254. 111. Rose JKC, Braam J, Fry SC, Nishitani K.. USA. Rose JKC, Braam J, Fry SC, Nishitani K. The XTH Family of Enzymes Involved in Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylation and Endohydrolysis: Current Perspectives and. 46 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(48) a New Unifying Nomenclature. Plant Cell Physiol [Internet]. 2002 Dec 15;43(12):1421–35. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0008621596003254 112. Kaku T, Tabuchi A,. Japón. Kaku T, Tabuchi A, Wakabayashi K,. Wakabayashi K,. Kamisaka S, Hoson T. Action of. Kamisaka S, Hoson T.. Xyloglucan Hydrolase within the Native Cell Wall Architecture and Its Effect on Cell Wall Extensibility in Azuki Bean Epicotyls. Plant Cell Physiol [Internet]. 2002 Jan 15;43(1):21–6. Available from: http://academic.oup.com/pcp/article/43/1/ 21/1887223/Action-of-XyloglucanHydrolase-within-the-Native. 113. Torre F de la,. España. Torre F de la, Sampedro J, Zarra I,. Sampedro J, Zarra I,. Revilla G. AtFXG1 , an Arabidopsis. Revilla G.. Gene Encoding α-l-Fucosidase Active against Fucosylated Xyloglucan Oligosaccharides. Plant Physiol [Internet]. 2002 Jan 1;128(1):247–55. Available from:. 47 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(49) http://www.plantphysiol.org/lookup/doi/1 0.1104/pp.010508 114. Espinoza-Gallardo D,. Chile. Espinoza-Gallardo D, Contreras-Porcia. Contreras-Porcia L,. L, Ehrenfeld N. ß-glucanos, su. Ehrenfeld N.. producción y propiedades en microalgas con énfasis en el género Nannochloropsis (Ochrophyta, Eustigmatales). Rev Biol Mar Oceanogr [Internet]. 2017 Apr;52(1):33–49. Available from: http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci _arttext&pid=S071819572017000100003&lng=en&nrm=iso &tlng=en. 115. Wyman C, Decker S,. España. Wyman C, Decker S, Himmel M, Brady. Himmel M, Brady J,. J, Skopec C, Viikari L. Hydrolysis of. Skopec C, Viikari L.. Cellulose and Hemicellulose. In: Polysaccharides [Internet]. CRC Press; 2004. p. 1023–62. Available from: http://www.crcnetbase.com/doi/10.1201/ 9781420030822.ch43. 116. Furukawa T, Bello FO, Horsfall L.. Edinburgo. Furukawa T, Bello FO, Horsfall L. Microbial enzyme systems for lignin degradation and their transcriptional. 48 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(50) regulation. Front Biol (Beijing) [Internet]. 2014 Dec 17;9(6):448–71. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11515014-1336-9 117. Rodríguez ES.. España. Rodríguez ES. Caracterización molecular de lacasas de Pleurotus eryngii: expresión heteróloga de estas enzimas y aplicaciones en la degradación de contaminantes aromáticos. Tesis. Complutense de Madrid; 2006.. 118. Kubicek CP.. Finlandia,. Kubicek CP. The Actors: Plant Biomass. USA, Países. Degradation by Fungi. In: Fungi and. Bajos. Lignocellulosic Biomass [Internet]. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. p. 29–44. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/978111841 4514.ch2. 119. Niladevi KN.. India. Niladevi KN. Ligninolytic Enzymes. In: Biotechnology for Agro-Industrial Residues Utilisation [Internet]. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2009. p. 397–414. Available from:. 49 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(51) http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-14020-9942-7_22 120. Ruiz BA.. México. Ruiz BA. Estudio de las enzimas fenoloxidasas, proteasas y peroxidasas presentes en Rhizopus oryzae ENHE ”. Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa; 2013.. 121. Paliwal R, Rawat AP,. India. Rawat M, Rai JPN.. Paliwal R, Rawat AP, Rawat M, Rai JPN. Bioligninolysis: Recent Updates for Biotechnological Solution. Appl Biochem Biotechnol [Internet]. 2012 Aug 26;167(7):1865–89. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12010012-9735-3. 122. Wong DWS.. USA. Wong DWS. Structure and Action Mechanism of Ligninolytic Enzymes. Appl Biochem Biotechnol [Internet]. 2009 May 26;157(2):174–209. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12010008-8279-z. 50 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(52) 123. Conesa A, Punt PJ,. Países Bajos. Conesa A, Punt PJ, van den Hondel. van den Hondel. CAMJJ. Fungal peroxidases: molecular. CAMJJ.. aspects and applications. J Biotechnol [Internet]. 2002 Feb;93(2):143–58. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0168165601003947. 124. Martıń ez AT.. España. Martıń ez AT. Molecular biology and structure-function of lignin-degrading heme peroxidases. Enzyme Microb Technol [Internet]. 2002 Apr;30(4):425– 44. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S014102290100521X. 125. Valli K, Wariishi H, Gold MH.. USA. Valli K, Wariishi H, Gold MH. Oxidation of monomethoxylated aromatic compounds by lignin peroxidase: role of veratryl alcohol in lignin biodegradation. Biochemistry [Internet]. 1990 Sep 18;29(37):8535–9. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/bi00 489a005. 51 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(53) 126. Wariishi H, Gold MH.. USA. Wariishi H, Gold MH. Lignin peroxidase compound III. Mechanism of formation and decomposition. J Biol Chem [Internet]. 1990 Feb 5;265(4):2070–7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22 98739. 127. Kuwahara M, Glenn. USA. Kuwahara M, Glenn JK, Morgan MA,. JK, Morgan MA, Gold. Gold MH. Separation and. MH.. characterization of two extracelluar H 2 O 2 -dependent oxidases from ligninolytic cultures of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. FEBS Lett [Internet]. 1984 Apr 24;169(2):247–50. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1016/00145793%2884%2980327-0. 128. Gold MH, Kuwahara. USA. Gold MH, Kuwahara M, Chiu AA, Glenn. M, Chiu AA, Glenn. JK. Purification and characterization of. JK.. an extracellular H2O2-requiring diarylpropane oxygenase from the white rot basidiomycete, Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch Biochem Biophys [Internet]. 1984 Nov;234(2):353–62.. 52 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(54) Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/0003986184902807 129. PaszczyÅ„ski A,. Santiago de. PaszczyÅ„ski A, Huynh V-B, Crawford. Huynh V-B, Crawford. Chile. R. Enzymatic activities of an. R.. extracellular, manganese-dependent peroxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium. FEMS Microbiol Lett [Internet]. 1985 Aug;29(1–2):37–41. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/femsle/articlelookup/doi/10.1111/j.15746968.1985.tb00831.x. 130. Sutherland GRJ,. USA. Sutherland GRJ, Zapanta LS, Tien M,. Zapanta LS, Tien M,. Aust SD. Role of Calcium in Maintaining. Aust SD.. the Heme Environment of Manganese Peroxidase †. Biochemistry [Internet]. 1997 Mar;36(12):3654–62. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/bi96219 5m. 131. Janusz G, Pawlik A,. Polonia,. Janusz G, Pawlik A, Sulej J, Świderska-. Sulej J, Świderska-. EEUU. Burek U, Jarosz-Wilkołazka A,. 53 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(55) Burek U, Jarosz-. Paszczyński A. Lignin degradation:. Wilkołazka A,. microorganisms, enzymes involved,. Paszczyński A. genomes analysis and evolution. FEMS Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2017 Nov 1;41(6):941–62. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/femsre/article/ 41/6/941/4569254. 132. Martínez AT,. España. Martínez AT, Speranza M, Ruiz-Dueñas. Speranza M, Ruiz-. FJ, Ferreira P, Camarero S, Guillén F, et. Dueñas FJ, Ferreira P,. al. Biodegradation of lignocellulosics:. Camarero S, Guillén. microbial, chemical, and enzymatic. F, et al.. aspects of the fungal attack of lignin. Int Microbiol [Internet]. 2005 Sep;8(3):195– 204. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16 200498. 133. Sigoillot J-C, Berrin J- Francia. Sigoillot J-C, Berrin J-G, Bey M, Lesage-. G, Bey M, Lesage-. Meessen L, Levasseur A, Lomascolo A,. Meessen L, Levasseur. et al. Fungal Strategies for Lignin. A, Lomascolo A, et al.. Degradation. In: Advances in Botanical Research [Internet]. 1st ed. Elsevier Ltd.; 2012. p. 263–308. Available from:. 54 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(56) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12416023-1.00008-2 134. Manavalan T,. India. Manavalan T, Manavalan A, Heese K.. Manavalan A, Heese. Characterization of Lignocellulolytic. K.. Enzymes from White-Rot Fungi. Curr Microbiol [Internet]. 2015 Apr 9;70(4):485–98. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00284014-0743-0. 135. Mayer AM, Staples. Israel. RC.. Mayer AM, Staples RC. Laccase: new functions for an old enzyme. Phytochemistry [Internet]. 2002 Jul;60(6):551–65. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0031942202001711. 136. Kramer KJ, Kanost. USA. Kramer KJ, Kanost MR, Hopkins TL,. MR, Hopkins TL,. Jiang H, Zhu YC, Xu R, et al. Oxidative. Jiang H, Zhu YC, Xu. conjugation of catechols with proteins in. R, et al.. insect skeletal systems. Tetrahedron [Internet]. 2001 Jan;57(2):385–92. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0040402000009492. 55 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(57) 137. Claus H.. Alemania. Claus H. Laccases and their occurrence in prokaryotes. Arch Microbiol [Internet]. 2003 Mar 7;179(3):145–50. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00203002-0510-7. 138. Baldrian P.. República. Baldrian P. Fungal laccases – occurrence. Checa. and properties. FEMS Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2006 Mar;30(2):215–42. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/femsre/articlelookup/doi/10.1111/j.15744976.2005.00010.x. 139. Dwivedi UN, Singh P,. India. Pandey VP, Kumar A.. Dwivedi UN, Singh P, Pandey VP, Kumar A. Structure–function relationship among bacterial, fungal and plant laccases. J Mol Catal B Enzym [Internet]. 2011 Feb;68(2):117–28. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcatb.2010. 11.002. 140. Levasseur A,. Francia. Levasseur A, Lomascolo A, Chabrol O,. Lomascolo A, Chabrol. Ruiz-Dueñas FJ, Boukhris-Uzan E, Piumi. O, Ruiz-Dueñas FJ,. F, et al. The genome of the white-rot. 56 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(58) Boukhris-Uzan E,. fungus Pycnoporus cinnabarinus: a. Piumi F, et al.. basidiomycete model with a versatile arsenal for lignocellulosic biomass breakdown. BMC Genomics [Internet]. 2014;15(1):486. Available from: http://bmcgenomics.biomedcentral.com/a rticles/10.1186/1471-2164-15-486. 141. Morpurgo L, Graziani. Italia. Morpurgo L, Graziani MT, Finazzi-Agrò. MT, Finazzi-Agrò A,. A, Rotilio G, Mondovì B. Optical. Rotilio G, Mondovì B.. properties of japanese-lacquer-tree ( Rhus vernicifera ) laccase depleted of type 2 copper(II). Involvement of type-2 copper(II) in the 330nm chromophore. Biochem J [Internet]. 1980 May 1;187(2):361–6. Available from: http://www.biochemj.org/cgi/doi/10.1042 /bj1870361. 142. Madhavia V, Lele SS.. India. Madhavia V, Lele SS. LACCASE: PROPERTIES AND APPLICATIONS. BioResources [Internet]. 2009;4(4):1694– 717. Available from: http://www.biochemj.org/cgi/doi/10.1042 /bj1870361. 57 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(59) 143. Nunes CS,. Francia,. Nunes CS, Kunamneni A. Laccases—. Kunamneni A.. España, USA. properties and applications. In: Enzymes in Human and Animal Nutrition [Internet]. Elsevier; 2018. p. 133–61. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12805419-2.00007-1. 144. Dooley DM, Rawlings USA. Dooley DM, Rawlings J, Dawson JH,. J, Dawson JH,. Stephens PJ, Andreasson L-E,. Stephens PJ,. Malmstrom BG, et al. Spectroscopic. Andreasson L-E,. studies of Rhus vernicifera and Polyporus. Malmstrom BG, et al.. versicolor laccase. Electronic structures of the copper sites. J Am Chem Soc [Internet]. 1979 Aug;101(17):5038–46. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ja00 511a039. 145. Gianfreda L, Xu F, Bollag J-M.. Inglaterra. Gianfreda L, Xu F, Bollag J-M. Laccases: A Useful Group of Oxidoreductive Enzymes. Bioremediat J [Internet]. 1999 Jan;3(1):1–26. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1 080/10889869991219163. 58 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(60) 146. Giardina P, Faraco V,. Italia. Giardina P, Faraco V, Pezzella C,. Pezzella C, Piscitelli. Piscitelli A, Vanhulle S, Sannia G.. A, Vanhulle S, Sannia. Laccases: a never-ending story. Cell Mol. G.. Life Sci [Internet]. 2010 Feb 22;67(3):369–85. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00018009-0169-1. 147. Malkin R, Malmström. USA. BG.. Malkin R, Malmström BG. The State and Function of Copper in Biological Systems. In: Advances in enzymology and related areas of molecular biology [Internet]. 2006. p. 177–244. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/43 18312. 148. Chevalier T, de Rigal. Francia. Chevalier T, de Rigal D, Mbéguié-A-. D, Mbéguié-A-. Mbéguié D, Gauillard F, Richard-Forget. Mbéguié D, Gauillard. F, Fils-Lycaon BR. Molecular cloning. F, Richard-Forget F,. and characterization of apricot fruit. Fils-Lycaon BR.. polyphenol oxidase. Plant Physiol [Internet]. 1999 Apr 1;119(4):1261–70. Available from:. 59 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(61) http://www.plantphysiol.org/lookup/doi/1 0.1104/pp.119.4.1261 149. Omiadze NT,. Georgia. Omiadze NT, Mchedlishvili NI, Abutidze. Mchedlishvili NI,. MO. Phenoloxidases of perennial plants:. Abutidze MO.. Hydroxylase activity, isolation and physiological role. Ann Agrar Sci [Internet]. 2018 Jun;16(2):196–200. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S1512188718300885. 150. Sánchez-Ferrer Á,. España. Sánchez-Ferrer Á, Neptuno Rodríguez-. Neptuno Rodríguez-. López J, García-Cánovas F, García-. López J, García-. Carmona F. Tyrosinase: a comprehensive. Cánovas F, García-. review of its mechanism. Biochim. Carmona F.. Biophys Acta - Protein Struct Mol Enzymol [Internet]. 1995 Feb 22;1247(1):1–11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/78 73577. 151. Decker, Dillinger, Tuczek.. Alemania. Decker, Dillinger, Tuczek. How Does Tyrosinase Work? Recent Insights from Model Chemistry and Structural Biology This work was supported by the. 60 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(62) Medicine and Science Center of the University of Mainz (H.D.) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (F.T., R.D.). The authors thank M.Mö. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl [Internet]. 2000 May 2;39(9):1591–5. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/%28SICI% 2915213773%2820000502%2939%3A9%3C159 1%3A%3AAIDANIE1591%3E3.0.CO%3B2-H 152. Pruidze G.,. Georgia. Pruidze G., Mchedlishvili N., Omiadze. Mchedlishvili N.,. N., Gulua L., Pruidze N. Multiple forms. Omiadze N., Gulua L.,. of phenol oxidase from Kolkhida tea. Pruidze N.. leaves (Camelia Sinensis L.) and Mycelia Sterilia IBR 35219/2 and their role in tea production. Food Res Int [Internet]. 2003 Jan;36(6):587–95. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0963996903000061. 153. Liu L, Dean JFD,. USA. Liu L, Dean JFD, Friedman WE,. Friedman WE,. Eriksson KL. A laccase-like. Eriksson KL.. phenoloxidase is correlated with lignin. 61 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(63) biosynthesis in Zinnia elegans stem tissues. Plant J [Internet]. 1994 Aug;6(2):213–24. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1046/j.1365313X.1994.6020213.x 154. Coll PM, Fernández-. España. Coll PM, Fernández-Abalos JM,. Abalos JM,. Villanueva JR, Santamaría R, Pérez P.. Villanueva JR,. Purification and characterization of a. Santamaría R, Pérez. phenoloxidase (laccase) from the lignin-. P.. degrading basidiomycete PM1 (CECT 2971). Appl Environ Microbiol [Internet]. 1993 Aug;59(8):2607–13. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1046/j.1365313X.1994.6020213.x. 155. Hendel B, Sinsabaugh RL, Marxsen J.. Alemania. Hendel B, Sinsabaugh RL, Marxsen J. Lignin-Degrading Enzymes: Phenoloxidase and Peroxidase. In: Methods to Study Litter Decomposition [Internet]. Berlin/Heidelberg: SpringerVerlag; 2005. p. 273–7. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/1-40203466-0_37. 62 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

(64) 156. Jassey VEJ, Chiapusio. Francia. Jassey VEJ, Chiapusio G, Gilbert D,. G, Gilbert D,. Toussaint M-L, Binet P. Phenoloxidase. Toussaint M-L, Binet. and peroxidase activities in Sphagnum-. P.. dominated peatland in a warming climate. Soil Biol Biochem [Internet]. 2012 Mar; 46:49–52. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/p ii/S0038071711004032 Tabla 1. Muestra de los autores identificados y su país de origen. Fuente: Elaboración Propia.. Como puede observarse, entre los países en los que más se ha estudiado el tema y que recientemente han publicado resultados de investigaciones, se destacan USA, España, India y Alemania; en esta revisión 58 documentos fueron realizados por autores estadounidenses, 36 en España, 11 en India y 13 en Alemania. Entre los estudios realizados en Colombia, se incluyen 3, pero cabe resaltar que estos han sido realizados en años recientes. A continuación, en el siguiente capitulo se desarrolla de manera sistematica el análisis relacionado con el objetivo del presente estudio.. 63 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

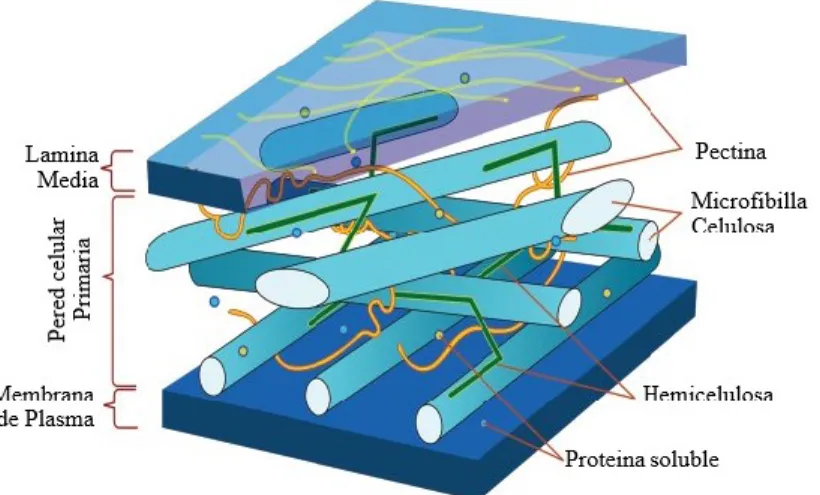

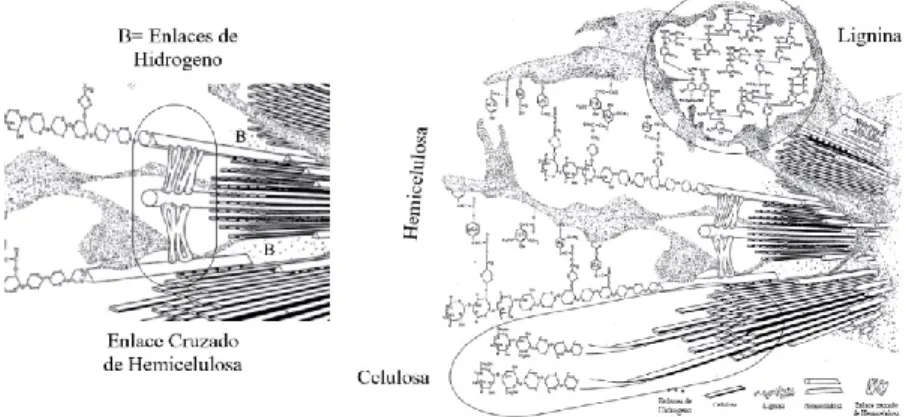

(65) 5. Fibra Las plantas son la fuente primaria de fibra que conforma la pared celular y que tiene la capacidad de expandirse durante el crecimiento y desarrollo de la célula vegetal, ejerciendo control de la cohesión tisular, intercambio iónico y defensa (Somerville, y otros, 2004, pág. 306). En la fotosíntesis la mayor parte del carbono se incorpora a los polímeros de la pared vegetal, compuesta por polisacáridos de alto peso molecular que son principalmente celulosa “homopolisacáridos”, hemicelulosas “heteropolisacáridos” (xilano, glucuronoxilano, xiloglucano, arabinoxilano, glucano de enlace mixto o glucomanano) y “polisacáridos no amiláceos” o pecticos los cuales son carbohidratos insolubles (Burton , Gidley, & Fincher, 2010, págs. 724–32); la lignina es un compuesto polifenól, conformado por tres tipos de unidades principales p-hidroxifenilo (H), guaiacilo (G) y siringilo (S), depositados en las paredes celulares secundarias, es esencial para la estructural de la pared celular que confiere rigidez y resistencia al tallo y raíz (Zhao & Dixon, 2011, págs. 227–33). La fibra también posee pequeñas cantidades de proteínas solubles, cutinas, ácido fítico y almidón resistente (Martínez, Rincón , Periago, Ros, & López, 1993, págs. 229–46) (Potty, 1996, págs. 1–18). Dicho esto, dependiendo de la especie vegetal cambia las proporciones de los compuestos que conforman la estructura bilógica en función del tipo de planta y/o su estado fenológico, afectando proporcionalmente la fisiología digestiva de quienes la consumen (Savon, 2002, págs. 91–102). Estas variaciones en la composición de materias primas pueden darse también por causas ambientales (Templeton, Sluiter, Hayward, Hames, & Thomas, 2009, págs. 621–39). 5.1.Estructura de la Fibra Vegetal Las células vegetales tienen dos tipos principales de paredes: la primaria y pared celular secundaria, estas dos están cementadas por una laminilla media (Cosgrove, 2005, págs. 850–61),. 64 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercialCompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional..

Figure

Outline

Documento similar

Esta obra ha sido publicada bajo la licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No Comercial-Compartir bajo la misma licencia 2.5 Perú.. ii

Esta obra ha sido publicada bajo la licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No Comercial-Compartir bajo la misma licencia 2.5

Esta obra ha sido publicada bajo la licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No Comercial-Compartir bajo la misma licencia 2.5

Esta obra ha sido publicada bajo la licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No Comecial-Compartir bajo la misma licencia 2.5 Perú. Para ver una copia de dicha licencia,

Esta obra ha sido publicada bajo la licencia Creative Commons. Compartir bajo la misma licencia versión Internacional. Para ver una copia de dicha licencia,

Esta obra ha sido publicada bajo la licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No Comercial-Compartir bajo la misma licencia 2.5 Perú.. Esta obra ha sido publicada bajo la

Esta obra ha sido publicada bajo la licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No Comercial-Compartir bajo la misma licencia 2.5 Perú. Para ver una copia de dicha licencia,

Esta obra ha sido publicada bajo la licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No Comercial-Compartir bajo la misma licencia 2.5 Perú.. INDICE