Childrení skepticism toward television advertising

Texto completo

(2) © Copyright. by. Silvia del Socorro González García. 2004.

(3) CHILDREN'S SKEPTICISM TOWARD TELEVISION ADVERTISING by Silvia del Socorro González García. Dissertation. Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Business Administration and Leadership (EGADE) of the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of. Doctor of Philosophy in Management Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey. August, 2004.

(4) CHILDREN'S SKEPTICISM TOWARD TELEVISION ADVERTISING. Approved by Dissertation Committee:. Dr. Wayne D. Hoyer, Main Advisor, Professor of Marketing. Dr. Robert A. Peterson, Advisor, Professor of Marketing. Dr. Carlos R. Martinez, Advisor, Professor of Marketing. Dr. Alejandro Ibarra Yunez, Director of Doctoral Program.

(5) ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND LEADERSHIP, INSTITUTO TECNOLOGICO Y DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES DE MONTERREY, CAMPUS MONTERREY. Degree: Doctor of Philosophy. Program: Doctoral Program in Management. Name of the Candidate: Silvia del Socorro González García Main Advisor: Dr. Wayne D. Hover. Title: CHILDREN'S SKEPTICISM TOWARD TELEVISION ADVERTISING. The aims of this work were to explore whether children exhibit skepticism toward televsion advertising and to examine the possible influence of socialization agents such as family, peers, and media on children's skepticism toward television advertising using socialization theory as a framework. Skepticism was defined as a tendency to disbelieve advertising claims. Advertising skepticism was conceptualized as an outcome of a socialization process. Specifically, the study investigated whether children from 8 to 12 years of age exhibit skepticism toward advertisng. Additionally, parents' skepticism, the type of family communication (socio-oriented versus concept-oriented communication), children's susceptibility to peer influence (susceptibility to informational versus normative peer influence), and the extent of.

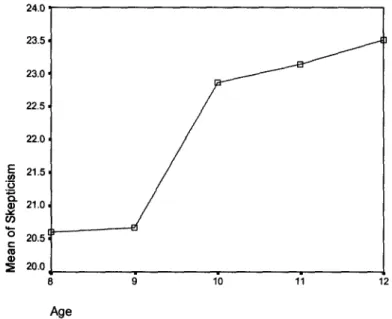

(6) television viewing were investigated regarding the relationship to children's skepticism toward television advertising. In order to shed light on the relationship among these variables, children's market knowledge was assessed as a possible mediator of the effects of socialization agents on children's skepticism. Demographic data (age, gender, type of school, socioeconomic status, number of children, birth order, amount of allowance, and source of the money) were also investigated as possible covariates of skepticism toward television advertising. Two studies were conducted with children from 8 to 12 years old and their parents. In Study 1 participants were 221 children, and in Study 2 participants were 662 children and 251 parents. The results shown evidence of increasing skepticism toward advertising in children from 8 to 12 years of age. A significant relationship was found between television viewing behavior and children's skepticism toward television advertising. To our knowledge this is the first study of children's skepticism toward advertising conducted in Mexico..

(7) To Jose Angel, Oscar, Eugenia, and Jorge. To my parents, Jesus and Sylvia..

(8) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Wayne D. Hoyer and Dr. Robert A. Peterson for their guidance throughout these years. Their helpful comments and suggestions in all the stages of this project were valuable. Their dedication and patience made me feel welcome in my foster academic home, The University of Texas at Austin. I appreciate the support of Dr. Carlos R. Martinez and Dr. German Otálora, from EGADE. I am very grateful to the faculty at both universities, which gave me lots of insights in the long way to the dissertation. Without the love and generosity of my husband, Jose Angel, and my children, Oscar, Eugenia, and Jorge, it would have been impossible to even think that I could be involved in this endeavor. They gave me time and space with enormous generosity. My parents, relatives, and friends also gave me their valuable help many times. Sol Elvira Perez, Diane Peterson, Jack and Gloria Garrison, Kristine Ehrich, Dan Laufer, Maria Merino, and Diane Wilson give me shelter and made Austin a very unique place for me. I thank all of them for their friendship and support. I will always keep in mind that "the role of professors is to create and disseminate knowledge," the first of many things that I have learned from Dr. Peterson.. vii.

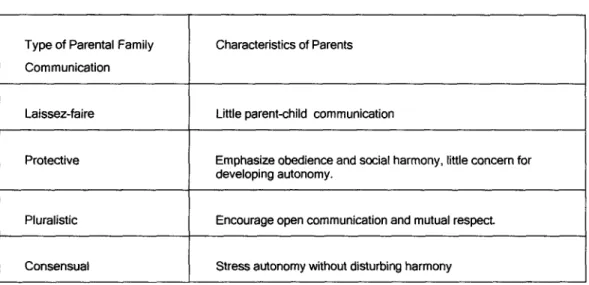

(9) Table of Contents. List of Tables. ix. List of Figures. x. Chapter 1: Introduction. 1. Children and Advertising. 2. Children's Skepticism toward Advertising. 6. Goals of the Dissertation. 8. Organization of the Dissertation. 13. Chapter 2: Literature Review. 16. Cognitive Development Theories. 17. Piaget's cognitive development theory. 18. Information-processing theories of cognitive development. 22. Social Development Theories. 24. Vygotsky's social cognitive approach. 24. Selman's social perspective-taking theory. 28. Consumer Socialization. 32. Children's Socialization as Consumers. 33. Theory of Mind. 36. Emerging conception of the mind. 38. Theories of mind, persuasion knowledge, and marketplace social intelligence. 39. Theory of mind and deception research. 42. Family Communication Patterns. 50. Family communication and children's socialization as viii.

(10) consumers. 51. Skepticism toward Advertising. 55. Children's Skepticism toward Advertising. 56. The development of skepticism in children Development of Hypotheses. 58 60. Children's skepticism toward television advertising. 61. Family socialization and skepticism. 62. Parents' skepticism toward television advertising. 65. Children's susceptibility to peer influence. 67. Television viewing and children's skepticism toward television advertising. 70. The moderating role of marketplace knowledge. 71. Chapter 3: Methodology. 76. Study One. 76. Participants. 77. Dependent Variables. 79. Marketplace knowledge. 79. Skepticism toward television advertising. 81. Independent Variables. 84. Age. 84. School grade. 85. Pretesting. 85. Methods of Data Analysis. 86. Study Two. 87. Paticipants. 87. Dependent Variables. 89. Children's skepticism toward television advertising 89 ix.

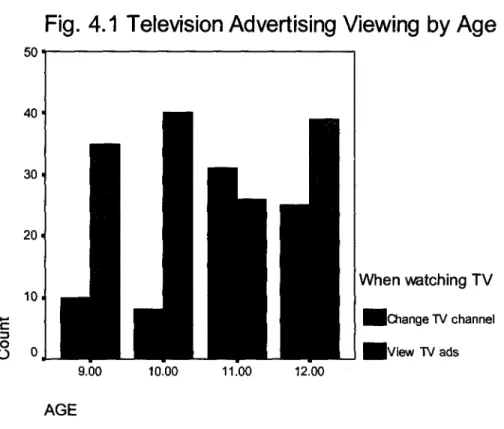

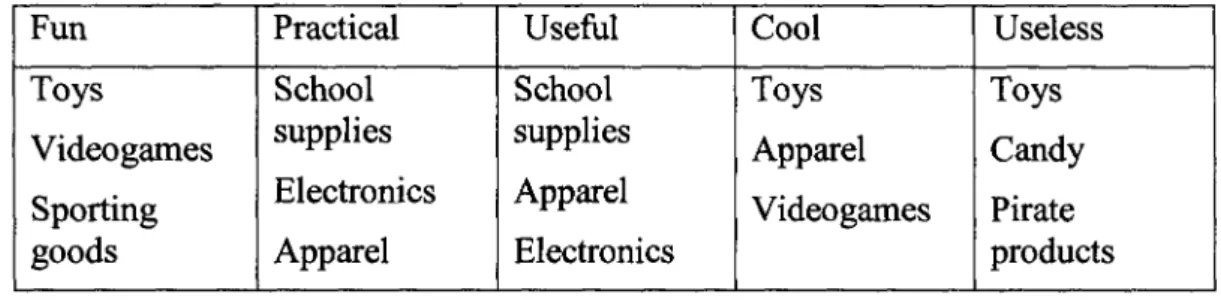

(11) Children's marketplace knowledge Independent Variables. 91 92. Parents' communication orientation. 92. Paternts' skepticism toward advertising. 93. Children's susceptibility to peer influence. 94. Children's television viewing. 94. Covariates. 95. Methods of Data Analysis. 95. Protection of Human Subjects. 98. Chapter 4: Analysis and Results. 99. Study One. 99. Children's Marketplace Knowledge. 99. Favorite products. 100. Product Prices. 101. Choice Tactics. 102. Television Viewing. 105. Attitudes Toward Private Brands. 106. Products That Children and Parent Buy. 107. Attitudes Toward Products and Brands. 107. Children's Attitudes Toward Television Advertising. 109. Summary of Study One. 110. Study Two. 110. Tests of Hypotheses. 112. Age. 112. Parent's orientation to family communication. 114. Parent's skepticism. 117. Children skepticism and peer influence. 117. Children's skepticism and television viewing. 119. x.

(12) Marketplace Knowledge Summary of Study Two. 119 122. Chapter 5: Discussion. 123. Children's Skepticism and Age. 125. Children's Skepticism and Socialization Agents. 127. Parents. 127. Peers. 130. Television. 131. Implications of Results. 132. Limitations. 136. Future Research. 137. References. 140. Appendix A:. 155. Vita. 159. xi.

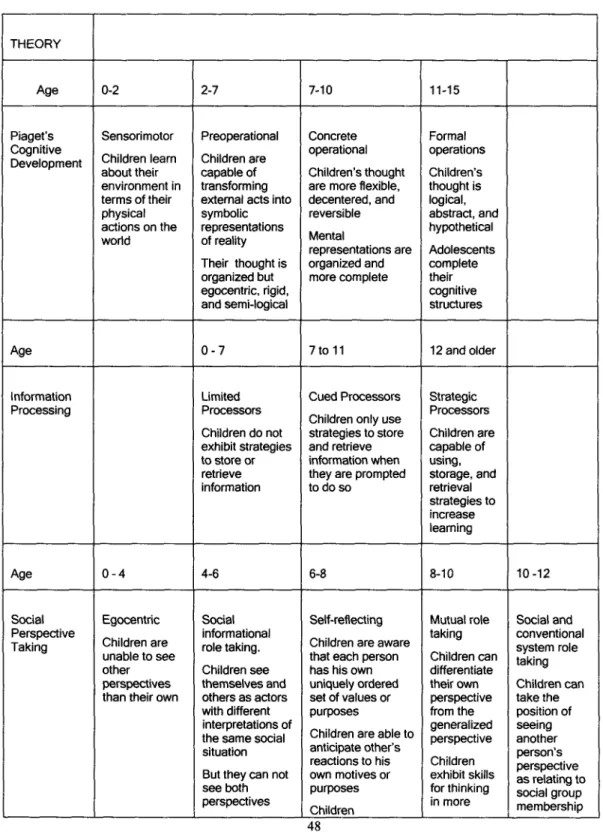

(13) Tables Table 2.1. Theoretical Frameworks of Children Cognitive and Social Development. Table 2.2. Family Communication Patterns. Table 4.1. Children's Choice Tactics. Table 4.2. Children's opinions of store (private) brands. Table 4.3. Children's evaluations by product category. Table 4.4. Component Correlation Matrix of the Rossiter Scale. Table 4.5. Percentage of participants by age, grade, gender, and type of school. Table 4.6. Component Correlation Matrix of Parents' Concept Orientation Scale. Table 4.7. Component Correlation Matrix of Parents' Socio Orientation Scale. xii.

(14) Figures Fig. 2.1. A Basic Model of Children's Skepticism toward Television Advertising. Fig. 4.1 Television Advertising Viewing by Age Fig. 4.2 Children's Skepticism by Age Fig. 4.3 Percentages of Family Communication Orientations. xiii.

(15) Chapter 1: Introduction Children represent a market with more potential than any other demographic segment because they are three markets in one (McNeal, 1999). Their potential comes from three factors: from their actual spending power, from their potential influence on their family purchases, and from their potential as future consumers. Clear evidence of the increasing importance of children as consumers is the growing numbers of companies that now are targeting them and the growing marketing communication expenditures on them (McNeal, 1999). McNeal (1999) reported that annual marketing expenditures were more than one billion dollars on media advertising to children, 4.5 billion dollars in promotion, two billion dollars on public relations, and three billion dollars in packaging especially designed for them. In addition, there has been a growing interest in children by social marketers, trying to persuade them to have positive attitudes toward social concepts (i.e., anti-smoking and anti-drug behavior). Most of the research aimed at children as consumers is focused on the impact of advertising to children. Still, there is a paucity of existing knowledge about how children develop attitudes to cope with persuasive intents. Skepticism toward advertising is an attitude to cope with persuasive messages (Bracks, Armstrong, & Goldberg, 1988). However, there is a lack of studies exploring this skepticism, specifically in the context of children. Literature regarding the study of children as l.

(16) consumers will be reviewed in this chapter to frame the relevance of children's skepticism toward advertising. Then, the goals and possible contributions of this dissertation will be discussed. Finally, an overview of the following chapters will be presented.. Children and Advertising Children and advertising is a relevant topic for several groups. Each of these groups has a different perspective from which advertising to children is seen. In today's market, parents, marketers, researchers, and public-policy makers face the challenge of understanding children who seem to be "older" at younger ages, more independent as consumers, more affluent, and more skeptical toward marketing activities than their predecessors (McNeal, 1999). Moreover, parents, marketers, researchers, and public-policy makers have different agendas regarding children, with the agendas contributing to a divergence in perspectives and conceptualizations about children (Le Bigot, 1980). Parents are the primary socialization agents of their children as consumers. They introduce their children to retail stores, show them how to use products, provide examples for interacting with sales personnel, and teach them scripts for buying. In fact, the home environment is the most important place for training children in consumption (McNeal, 1987). Parents possess different parental styles for rearing 2.

(17) children as a result of demographic, economic, cultural, and social factors (Le Bigot, 1980). Marketers have been interested in children as consumers because they allegedly constitute three different markets. First, they constitute a primary market. Many products are aimed directly at satisfying children's needs (e.g., food, toys, and clothes). In contrast with past generations, the present children's market is valued in billions of dollars (Acuff & Reiher, 1997; McNeal, 1992, 1999). Second, children constitute an influence market in terms of influencing adults to buy products (Caruana & Vassallo, 2003). Third, since some patterns of adult consumer behavior are influenced by childhood experiences, there is a future market comprised of children who at some point will be adult consumers (McNeal, 1998,1999). Scholarly research examining children as consumers began several decades ago. For example, researchers have examined children's loyalty to brands (Guest, 1942, 1955), conspicuous consumption (Reisman & Roseborough, 1955), and patterns of consumption. In the 1960s, research focused mainly on advertising to children (McNeal, 1964). The debate regarding advertising to children heated up in the 1970s, slowed down in the 1980s, and accelerated in the 1990s because advertising to children was regulated or banned in some countries (Pine & Veasey, 2003). It continues to the present day..

(18) Supporters of advertising to children argue that a commercial is a source of information that helps children learn the skills that they need to operate in the marketplace. It is claimed that commercials teach children how to buy; that today's adults have been exposed to many commercials as children and show no ill effects; and, finally, that controlling, restricting or banning advertising violates advertisers' freedom of speech directed to their targeted audiences (Hite & Eck, 1987). Critics of advertising to children have argued that advertising creates materialistic children and promotes conflict between parents and children. Another criticism is that advertising toward children is unfair and deceptive. Advertising to children is considered to be inherently unfair because of younger children's inability to interpret the selling intent of the message or tell the difference between a television program and commercials, and because children are thought to do and think what adults tell them to do and think (Wright, 1999, personal communication). Although most scholarly research on advertising to children has been carried out in the United States and Canada, there has been a growing interest in this topic globally. The debate is now prevalent in Europe and is illustrated by the fact that advertising targeted to children was banned in Sweden recently (Pine & Veasey, 2003). According to Martensen and Tufte (2002), research on advertising to children gradually has emerged on the agenda of European researchers..

(19) The topic has also been addressed in Asia, particularly in China because of its one-child family planning policy (Chan, 2000; Chan & McNeal, 2004; McNeal, 2000; McNeal & Chan, 2003; McNeal & Ji, 1998; McNeal & Yeh, 1990; Williams & Veeck, 1998). Nevertheless, cross-cultural research on advertising to children is emerging slowly. Keillor, Parker, and Schaefer (1996) studied the information sources used by Mexican and American adolescents to form brand preferences. Rose (1999) compared consumer-related developmental timetables between the United States and Japan. Similarly, Rose, Dalakas, and Kropp (2003) examined consumer socialization and parental style in Australia, Greece, and India. However, until now there has been a paucity of cross-cultural studies focusing on children as consumers, including children's skepticism toward television advertising. Research findings regarding children as consumers may be beneficial to policy-makers. In Latin America there appears to be no governmental regulations expressly aimed at advertising to children. In addition, although Mexico passed a federal consumer protection law —Ley Federal de Protection al Consumidor— in 1974 and amended it in 2004, it did not include any particular mention of advertising to children (Profeco, 2004). Research with Mexican children as conducted for this dissertation may be useful to these organizations to promote better consumer-related laws, specifically related to children as consumers..

(20) Advertising to children is a very controversial issue due to the different perspectives of many stakeholders -parents, marketers, researchers, and public-policy makers, each with different interests and resources. The discussion of this issue continues among scholars, clearly suggesting that more research is needed. Although advertising to children is a topic that has been extensively researched, there are related phenomena and variables that have not been sufficiently explored. Some researchers believe that previous efforts have overlooked what children do to understand and interpret commercials, or missed the child's perspective to advertised messages (Lawlor & Prothero, 2002, Seiter, 1993). Other researchers believe there is a need to examine the effects of advertising reported in past research because "children's abilities to understand 'the grammar of television' may be underestimated in the literature of the 1970s" (Young, 1998, p. 4).. Children's Skepticism toward Advertising At the core of the discussion of children's understanding of advertising intent is their ability to recognize the persuasive intent of advertisers and the bias and deception in advertising (Barry, 1980; Bever, Smith, Bengen, & Johnson, 1975; Robertson & Rossiter, 1974; Ward, Wackman, & Wartella, 1977). Children's understanding of advertising intent is considered a pre-requisite for recognizing bias and deception in advertising, as well as for the development of cognitive defenses 6.

(21) against advertising. Awareness of bias and deception undoubtedly increases with a child's age, parallel to his or her cognitive development. The overall findings of research on the topic of advertising to children suggest that eight-year-olds recognize the existence of bias and deception in commercials (Bever et al., 1975; Robertson & Rossiter, 1974; Ward, 1972; Ward et al., 1977). However, Bearden, Teel, and Wright (1979) found differences in children from lower income status compared to children from higher status, and differences in children from different ethnic groups, suggesting that variables beside age may be playing a role regarding awareness of the intent of advertising. One possible explanation of these effects could be if children have or have not access to specific training of critical thinking skills and independent thinking. Past research has shown that adolescents have negative attitudes and are skeptical of advertising in general (Mangleburg and Bristol, 1998). Roedder John (1999) suggested that skepticism among teenagers seems to be associated with the development of independent thinking and access to other sources of information. Mangleburg and Bristol (1998) presented evidence of this in a study of skepticism toward advertising. It is possible to think in terms of a lack of skepticism being correlated with easy acceptance of persuasive messages (Fujioka & Austin, 2002). Thus, children "without these cognitive defenses are seen as an at-risk population for being easily mislead by advertising" (Roedder John, 1999, p. 190). Therefore,.

(22) skepticism regarding advertising is critical to promote in children because it is considered an effective way to cope with advertising persuasive intent (Brucks et al., 1988).. Goals of the Dissertation In summary, studies of adolescents show that skepticism is a well-developed skill. However, although the number of studies about children and media is substantial, there is sparse research on children's skepticism toward advertising, particularly among children 8 to 12 year old. This age span needs to be explored for several reasons. First, children as early as eight clearly understand the commercial intent of advertising. Second, children spend many hours a day in media use, most of them viewing television. Third, television advertising is not the only source of consumer socialization. Others sources, such as peers and school, may play an important role in promoting skepticism toward advertising. Finally, children's skepticism toward advertising in children may be correlated with a particular parental style of communication and parents' skepticism. The goals of this dissertation are to explore the role of parents, peers, and media on children's skepticism toward television advertising using socialization theory as a framework. Skepticism toward advertising is defined loosely as "a tendency to disbelieve advertising claims" (Obermiller & Spangenberg, 1998, p..

(23) 160). Advertising skepticism is conceptualized as an outcome of the socialization process. This study integrates several theoretical frameworks: child socialization, children's cognitive development, and child social development to explore children's skepticism toward advertising. Specifically, the study investigates the influence of the type of family communication (socio-oriented versus concept-oriented communication), parental skepticism, children's susceptibility to peer influence (susceptibility to informational versus normative peer influence), and the extent of television viewing on children's skepticism toward television advertising. In order to shed light on the relationships among these variables, measures of children's market knowledge and involvement with advertising were assessed as possible mediators of effects of socialization agents -parents, peers, and television- on children's skepticism. Demographic data (age, gender, type of school, socioeconomic status, number of children in a family, birth order of the child, amount of allowance, and source of allowance) were also measured and investigated. The study extends previous work on adolescents' skepticism (e.g., Boush, Friestad, & Rose 1994; Mangleburg & Bristol 1998) to children from 8 to 12 years old and incorporates a measure of parental skepticism. Skepticism maybe a specific attitude that some parents may communicate to their children, explicitly or implicitly, through cultural or psychological variables or even situational variables. Therefore,.

(24) parental skepticism toward advertising and children's perception of family communication were included as variables in the socialization process. This investigation will address several research questions: Are children from 8 to 12 years old skeptical of television advertising? If children in this age bracket are skeptical, are there some patterns of family communication that foster children's skepticism toward advertising? Is there a correlation between the level of parents' skepticism toward advertising and the level of skepticism in their offspring? Is there a correlation between the level of children's advertising skepticism and their susceptibility to peer influence? Is there a relationship between children's skepticism toward advertising and their market knowledge? Is there relationship between children's advertising skepticism and their exposure to television advertising? Are demographic variables related to children's skepticism toward advertising? As previously noted, parents are considered the primary socialization agents for their children (McNeal, 1987). Parents foster the development of their children's consumer skills by training them implicitly and explicitly (Moschis, 1985; Ward et al., 1977), and they initiate and control their children's interactions with other socialization agents like peers, salespersons, and media. However, even when parental socialization is considered a universal process, the pervasiveness of specific patterns of parental styles in certain culture may change because of demographic, economic, and/or social factors (Keillor et al., 1996; Le Bigot, 1980; Rose, 1999; 10.

(25) Rose et al,. 2003). Socialization is a process embedded in the cultural venue. Consumer socialization may provide insights on how children acquire attitudes about the marketplace worldwide. Ward defined consumer socialization as "processes by which young people acquire skills, knowledge, and attitudes relevant to their functioning as consumers in the marketplace" (1974, p. 2). This conceptualization is applicable to all cultures. However, little research examines how different cultures enact this process. Most of the research has been done with children in the United States, only a small percentage of the research reported in the literature has non-U.S. children as subjects. According to Rose, Boush, and Kahle (1998), children globally represent an opportunity to study attitudes toward advertising and family communication patterns. Cognitive developmental psychologists put major emphasis on the influence of peers in childhood socialization. However, there are only a few consumer research studies examining the role of peer interactions in children's consumer socialization. Those that exist have been done mainly with adolescents. Findings show that as children get older, parental influence decreases and peer influence increases (Moschis & Churchill, 1978; Ward, 1974). In addition, correlations between family communication patterns and peer influence in adolescents have been reported. Moschis and Moore (1982) reported strong peer influence in families where family communication regarding consumption is infrequent. Roedder John (1999) pointed. n.

(26) out that more research regarding the role of peer influence in children's socialization processes would be welcome, particularly studies that consider peer influence in younger children. There is sparse research done in Mexico or even in Latin America on children as consumers in general, or on children's reactions to advertising in particular. What has been done consists mainly of ad hoc, unpublished studies by media, advertising agencies, or market research agencies. The present dissertation is likely the first scholarly attempt to study children as consumers in Latin America generally, and particularly in Mexico. The potential contributions of the present study are several. The study assesses the extent to which research on adolescents and adults' skepticism toward advertising can be extended to children from 8 to 12 years old. It also integrates theoretically new variables into the children consumer socialization framework— parents' and children's skepticism toward advertising. Third, the study explores if research done in North America is valid for children in another market, such as Mexico, that possesses dissimilar cultural traits in the creation of marketing strategies. Finally, the study provides useful insights from a public policy perspective. Because of NAFTA, many global companies have become interested in Mexican consumers. Therefore, this investigation may have managerial implications. Additionally, the importance of the Hispanic market is growing in the United States, 12.

(27) and Mexican Americans account for 66 percent of this market (Sigma, 2003). Thus, research on Mexican children as consumers may also contribute to understanding the consumption behavior of Hispanic children.. Organization of the Dissertation The organization of this dissertation will be as follows. The goal of the dissertation and the antecedents of the study of children as consumers are described in Chapter 1. A review of several bodies of literature, ranging from developmental theories related to cognitive and social development of children, and the literature regarding children socialization and advertising, will provide the theoretical foundations for understanding age differences in children's skepticism toward advertising. This research and literature are reported in Chapter 2. One of the most cited theories used to study children as consumers is Piaget's theory of cognitive development (Macklin & Carlson, 1999). Piaget proposed four stages of cognitive development, sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operations, and formal operations. Through these stages, children's cognitive development form birth to adult thought is explained. In addition to Piaget's theory of child development, another perspective widely used in studying children is information-processing theory. Information processing theory explains children's cognitive development by focusing on children's processes to encode, organize, and retrieve information. 13.

(28) Children's processing skills are described in terms of three different stages: limited processors, cued processors, and strategic processors (Roedder, 1981; Roedder John, 1999, 2000). According to Macklin and Carlson (1999), little attention has been given to theories of social development, which they consider very useful for explaining how children develop skills to understand advertisers' motives and intent. Sehnan (1980) proposed a framework of social perspective taking, which considered five stages of social development: egocentric, social information role-taking, self-reflective, mutual role taking, and social and conventional system role taking. There is a lack of studies in the literature of children as consumers incorporating one of the latest developed frameworks in children's cognitive development, the theory of mind. Theory of mind research has explored children's knowledge about basic mental states like intentions, beliefs, knowledge, pretense, and thinking. This theory can be applied to understand the marketplace metacognition of children. Marketplace metacognition is loosely defined as individuals' everyday thinking about market-related knowledge (Wright, 2002). Finally, socialization factors including family and peers influences will be described to explore how they have an effect on children's attitudes toward advertising. The third chapter describes the methodology used in the empirical study, including the procedures used in selecting study participants, scales, and methods of data analysis. In the fourth chapter, the analysis of the study data and results will be 14.

(29) presented. The last chapter includes a discussion of the implications of the results, and the possible contributions and limitations of the study. It concludes with a discussion of future research.. 15.

(30) Chapter 2: Literature Review. The overall findings of research on the topic of advertising to children suggest that many adolescents are skeptical toward advertising. However, it is not clear how and when a child becomes a skeptical adolescent from an individual who does not recognize bias and deception in advertising. To understand how and when children become skeptical toward advertising, it is necessary to review cognitive and social development theories to gain some insight into the key variables related to skepticism toward advertising. Many theoretical frameworks have been employed to guide research on children's behavior. Despite the wide variety of theoretical frameworks, most studies of children's consumer behavior can be categorized into a limited number of general theoretical approaches. McNeal (1987) acknowledged this and argued that most of the studies explicitly or implicitly follow one of these few different theoretical approaches. Recurrent approaches to studying children as consumers incorporate cognitive development theories, information processing theories, socialization theories, and/or social development theories. Two bodies of literature will be reviewed to provide theoretical foundations for investigating children's skepticism toward advertising. Theories of children's cognitive and social development emanate from the psychology literature. Theories of cognitive and social development will be 16.

(31) reviewed due to their predominant role in understanding when children's cognitive abilities develop in the context of their role as consumers. The theory of consumer socialization from the marketing literature will also be reviewed. Children's cognitive abilities develop within their family's environment. Social interactions between parents and children play a key role in children's socialization processes. Therefore, the literature on parental communication patterns (Moschis, 1985) will be reviewed to understand the development of children's skepticism toward advertising. Consumer socialization theory and family patterns of communication are frequently used in the marketing literature to describe children's abilities and skills regarding their role as consumers. Demographic and behavioral variables are also used when researching children as consumers. Focal demographic variables include gender, children's discretionary income, family socioeconomic status, number of children in the family, birth order, and television viewing hours. Conceptualizations of the impact of these variables on children's skepticism toward advertising will be examined as well.. Cognitive Development Theories In order to understand the psychological processes underlying children's skepticism toward advertising, it is necessary to review several theoretical perspectives that might be relevant for understanding children's skepticism. These 17.

(32) theoretical perspectives are useful for comprehending children's cognitive and social development. Piaget 's cognitive development theory Piaget's theory of cognitive development is one of the most widely employed frameworks to study the cognitive processes of children. According to Flavell (2000), the earliest research on the development of children's knowledge about the mind is derived from Piaget's theory. Although Piaget characterized himself as a genetic epistemologist because his main interest was human knowledge, this interest led him to study how children's knowledge develops. Piaget's theory has been one of the most widely accepted theories of child development (Chan, 2000; Lawlor & Prothero, 2002). He studied several aspects of children's processes, including the development of children's thought, evolution of dreams and play, the use of symbols and numbers, moral judgments, perception, and intelligence (Flavell, 1963). Some authors (e.g., Flavell, 1963; Miller, 1993; Thomas, 2000) have summarized Piaget's theory of children's cognitive development in terms of four basic ideas. The first idea was the paramount role of intelligence. Although Piaget studied other processes (e.g., perception, moral attitudes, values, motivation, and logical reasoning), he often related them to intelligence. Second, to Piaget, intelligence was a biological adaptation; therefore, his theory had an evolutionary nature. Piaget (1952) considered cognitive development as a constant effort by 18.

(33) children to expand and refine their knowledge. For him, cognitive growth involved an organized structure that becomes differentiated over time. Third, Piaget's theory focused on the structure of developing intelligence, rather than its function or content (Flavell, 1963). That is, Piaget's conceptualization of development emphasized the structure of intelligence more than behavioral data from children performing tasks (content) or intelligence functions (organization and adaptation). The fourth basic idea in Piaget's theory is the use of qualitative stages to explain cognitive development. He conceptualized stages as periods of time in which the child's thinking and behavior show an underlying mental structure (Miller, 1993). Every stage derives from the previous one, all of which follow a precise order, and no stage can be passed over. Each stage is structured and in equilibrium (i.e., a stage is an integrated whole of organized parts). By the end of each stage, loosely organized mental structures become tightly organized ones (Flavell, 1963). Each stage has schemas that are interconnected to form an organized whole, a differentiated structure. Each structure allows qualitatively different types of interactions between an individual and his/her environment (Flavell, 1963; Miller, 1993). Piaget proposed four main stages of cognitive development: sensorimotor (birth to two years), during which infants learn about their environment in terms of their physical actions on the world (Piaget, 1952); preoperational (two to seven years), during which children are capable of transforming external acts into symbolic 19.

(34) representations of reality (semiotic functions) and their thinking is more organized. Children exhibit perceptual centration, which implies their perception is fixed on a single dimension or attribute. Preoperational children's thinking is still egocentric and rigid, and only semi-logical reasoning is exhibited (Flavell, 1963). Piaget termed the third stage concrete operational (seven to eleven years). In this stage, children's thoughts are more flexible, decentered, and reversible. Additionally, mental representations are organized and more complete (Flavell, 1963). In the final stage, formal operations (eleven to fifteen years), children's thoughts are logical, abstract, and hypothetical. Piaget described this stage as the last one when adolescents complete their cognitive structures. According to Piaget's theory, children evolve through each stage, from selfcentered individuals with no realistic knowledge of the environment to adolescents who understand realistically their environment and how it works (Thomas, 2000). This conceptualization of children's cognitive development, where children are seen as evolving through stages as if they were climbing stairs, has been very influential in the field of child development. Most theories pertaining to child development use similar stage models to describe children's cognitive development. Piaget emphasized the important role of cognition in children's development. Each stage corresponds to a given age group. This theory described children's knowledge and skills at different ages and specified the approximate ages at which 20.

(35) they progress. Although a child's age is not identical to his or her cognitive ability, most studies in children's consumer behavior that use cognitive development theories as a framework use children's age as a surrogate variable for cognitive ability (Roedder John, 1999). Thus, children's age will be used as a surrogate for children's cognitive abilities in the present research. Piaget (1952) suggested that differences among children regarding the age at which they achieve a particular stage are due to variations in four causal factorsheredity, physical experience with the world of objects, social transmission, and equilibrium. Piaget believed that these factors determine how adaptation and organization systems operate in a given child's development (Piaget & Inhelder, 1969). Thus, interpreting this assumption from a marketing perspective, individual variations in development may occur due to differences in children's intelligence, cultural background, social class, marketing knowledge, and advertising exposure. Even though Piaget's theory had an enormous impact on the child development literature, several criticisms have been raised. These criticisms are related to inconsistencies in Piaget's stages that have been reported and the lack of detail as to how the cognitive structures are translated into behavior (Miller, 1993). Piaget's theory, with its evolutionary perspective, focused on maturation as the primary factor driving children's transitions from egocentric individuals to adolescents who understand their environment. Studies have generally supported the 21.

(36) proposition that children's understanding increases with age, and no doubt age is a useful variable for categorizing children into cognitive age groups. The following theoretical frameworks depart from Piaget mainly because of the different emphases they present as to how children process information and the role of social variables in children's cognitive development. Information-processing theories of cognitive development From the perspective of information-processing theory, information or an input (stimulus) is attended to, transformed, interpreted, stored, and finally used to produce an output or response (Miller, 1993). Information-processing theories have focused on children's developing skills in the areas of acquisition, encoding, organization, and retrieval of information. Children's ages in Piaget's stages have been used to investigate how children perceive, categorize, discriminate, and evaluate products or brands. Roedder (1981) proposed a three-stage model for examining children's cognitive development depending on their abilities to process information. Children have been categorized as limited processors (under seven years old). In this stage, children do not exhibit strategies to store or retrieve information. Children seven to eleven years of age have been categorized as cued processors. In this stage, children only use strategies to store and retrieve information when they are prompted to do so.. 22.

(37) In the third stage, children twelve years and older are strategic processors. They are capable of using storage and retrieval strategies to increase learning (Roedder, 1981). From this perspective, Piaget's perceptual "centration" or perceptual "boundness" that characterizes younger children in the preoperational stage implies that they perceive stimuli unidimensionally. For example, perceptual centration makes children distinguish commercials and television programs based on one perceptual feature, (e.g., commercials are shorter). By the time children reach eight years of age (Piaget's concrete operation stage), they posses enough knowledge to be aware of advertising's persuasive intent and bias (Young, 2002). However, this knowledge is not necessarily accessed and used in evaluating advertising messages (Brucks et al., 1988). Roedder (1981) attributed children's need to be prompted to use evaluation strategies to the fact that their abilities are still developing and this knowledge is not easily accessed, even when children might have a good deal of knowledge about advertising. Roedder's information-processing theory and Piaget's theory are frameworks that conceptualize children's cognitive stages as having certain characteristics and have children evolve through the stages in a regular and predictable fashion. Young (2002) addressed some inconsistencies related to children's cognitive stages. He argued that, according to these theories, children twelve years of age, the age corresponding to Piaget's formal operations stage and Roedder's strategic processors 23.

(38) stage, might still have a problem understanding advertising. Young also suggested that there is some evidence that children between five and eight years old have a growing understanding of some aspects of advertising (e.g., the commercial intent behind advertising). One possible explanation is that these variations in children's skills may come from their social environments.. Social Development Theories Children do not develop in a vacuum. They develop in a social world. It is within a cultural context where social forces in children's interactions with peers and adults take place. It is important to take this fact into account when studying the cognitive development of children. Vygostky 's social cognitive approach Piaget considered children's cognitive stages as universal. He believed that culture had no effect on the sequence of development. However, it has subsequently been recognized that children progress though his developmental stages at different paces. In addition, information-processing theories do not explain why children in the cued processor stage are capable of using cognitive strategies when they are prompted to do so. One key aspect which has not been fully accounted for is the role of social factors in children's cognitive development. A key point of departure between Piaget and a Russian developmental psychologist, Lev Vygotsky, was the 24.

(39) role of social influence. Vygotsky focused on the role of social interactions with peers and adults within a cultural context as the driving force behind cognitive development. Piaget argued that there were four cognitive development causal factors, one of which was the social factor - the others being heredity, experience with physical objects, and equilibrium. Vygotksy focused more heavily on social influences in children's cognitive development. Vygotsky disagreed with the piagetan principle of internal maturation of a child's cognitive development. He believed that a child's informal and formal education through language influenced the level of conceptual thinking that is reached (Vygotsky, 1934/1987). He presumed that the cognitive skills or patterns of thinking that a person develops are products of activities practiced in the social institutions of the culture in which the individual grows up (Vygotsky, 1935/1978). Vygotsky proposed that "our schema of development - first social, then egocentric, and then inner speech- contrasts with Piaget's sequence - from non-verbal autistic thought and speech to socialized speech and logical thinking" (Vygotsky, 1934/1986, pp. 35-36). Vygotsky criticized Piaget's theory of development in terms of "this attempt to derive the logical thinking of a child and his entire development from pure dialogue of consciousness, which is divorced from practical activity and which disregards the social practice" (p. 52).. 25.

(40) Vygotsky proposed two different cognitive systems to explain children's cognitive development. One was a system for speech development and the other for conceptual thinking development. Eventually these two systems merge into one when children are about three years old. One of the most important concepts introduced by Vygotsky was the zone of proximal learning, which "is the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the potential development level determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers" (1935/1978, p. 86). Thus, Vygotsky clearly recognized the impact of socialization agents on knowledge development. Vygotsky pointed out that this guidance could occur by means of demonstration, leading questions, and by introducing the initial elements of a task's solution (p. 209). According to De Vries (2000), however, Vygotsky never specified the forms of social assistance that constitute guidance to learners in the zone of proximal learning. She added that this social assistance could take the form of "directive, authoritarian assistance as well as nondirective, cooperative assistance" (p. 195). Social assistance may vary from culture to culture. For example, Laosa (1982, 1984) has shown that Hispanic mothers are more directive, whereas Anglo mothers are more descriptive and make more comments about actions. De Vries (2000) 26.

(41) mentioned that Vygotsky's types of assistance seem to fall in the behaviorist paradigm because of the strong influence of conditioning processes from Pavlov's writings. In fact, according to De Vries (2000), Vygotsky aligned himself with the viewpoint of the American psychologist Thorndike and recognized that "the key to the child's control of his/her behavior lies in mastering the system of stimuli.. .but this system is a social force provided externally to the child" (p. 188). De Vries (2000) attempted to reconcile Piaget's and Vygotsky's theories. She argued that, as an epistemologist, Piaget was interested in the development of ideas, but as a child psychologist, Piaget certainly recognized the central role of social factors in the construction of knowledge. She even mentioned that, for her, "Piaget sounded like Vygotsky" (De Vries, 2000, p. 190), referring to when Piaget, in his early works, affirmed that social life is a necessary condition for the development of logic, that reason develops due to social mechanisms, and in later works, he noted that "relations among individuals.. .modify the mental structures of individuals" (Piaget, 1950/1995, p. 40 cited in De Vries, 2000). The key point, however, is that both cognitive orientations provide a basis for explaining the emergence of a variety of socialization outcomes in terms of children's consumer behavior. For example, consider perceptual development's impact on the knowledge of products and brands, symbolic meaning that children attached to. 27.

(42) products and brands, and the impact of different parental communication styles on children's skepticism toward advertising. Young (2002) argued that recent advances in research have overtaken the debate as to whether Piaget or Vygotsky was right in their different approaches. Selman's (1971, 1974, 1980) social perspective-taking theory is one of these advances in research that originated with Piaget's theory. According to Selman's theory, children's ability to take the perspective of other people should be taken into account when considering children's understanding of advertising. Young (2002) noted that the skill of understanding that some people will deceive people and we can also deceive others gives their possessors an evolutionary advantage. Similarly, other researchers have stated that understanding the commercial intent of advertising may help children develop cognitive defenses (Bracks et al., 1988). However, when can children understand the motives and intentions of advertisers? Selman proposed that Piaget's theory of children's cognitive development could be applied to the study of children's conception of the social world (Selman, 1971). This social world must include socialization agents such as parents, peers, and media. Selman's social perspective-taking theory. Social development in children includes moral development, altruism and prosocial development, impression formation, and social perspective taking. According to Roedder John (1999), social perspective taking (Selman, 1980) is 28.

(43) relevant to children's consumer behavior because it is strongly related to the social aspects of products and consumption. Social perspective taking involves the ability to see perspectives beyond one's own. Selman (1971) proposed that role taking is explicitly interpersonal in requiring the ability to infer another person's capabilities, expectations, feelings, and potential reactions. In that sense, role perspective taking is strongly related to Roedder John's purchase influence and negotiation skills because a child must consider other people' perspective to be able to persuade them (Roedder John, 1999). Selman's research was based on Piaget's conceptualization of cognitive "centration" applied to a social context. Children in Piaget's preoperational stage have a perceptual system as a primary intellectual instrument for organizing mental representations. A child's perceptual orientation is "centered" because the child focuses on situations in terms of static rather than dynamic characteristics. When the ability of role taking develops, a child is "decentering," that is, a child perceives social situations in more than one dimension. Thus, according to Selman (1971), role taking can be conceptualized as cognitive and social "decentering." Selman's (1980) and Vygotsky's (1934/1986) theories are useful for understanding the interaction between children and socialization agents. A child's ability to recognize and comprehend a message sender's agenda is a pre-requisite to understanding advertising. According to Selman (1980), children younger than six 29.

(44) years old are unable to take other perspectives than their own. Thus, children do not recognize another person's point of view, or in this case the persuasive intent of advertisements, until they are eight to ten years old. Selman (1980) elaborated a description of children's abilities to understand different perspectives that can be organized into five stages, the first of which is egocentric (children younger than four years old). Children in this stage are characterized by their inability to make a distinction between their personal interpretation of a social action, and the interpretation from another person of the same action. Children can differentiate entities, but are unable to differentiate viewpoints or relate perspectives. In the second stage, social informational role taking (four to six years of age), children see themselves and others as actors with different interpretations of the same social situation. Children are aware of different interpretations but attribute these differences in terms of different situations or different information of the participants. However, children still are unable to maintain their own perspective and simultaneously put themselves in the place of others. In the third stage, self-reflective role taking (six to eight years of age), children are aware that each person has his or her own uniquely ordered set of values or purposes. Children in this stage are able to anticipate other's reactions to their own motives or purposes. In the fourth stage, mutual role taking (eight to ten years of age), children can differentiate their own perspective from a generalized perspective 30.

(45) (i.e., children can be observers or spectators and maintain a disinterested point of view). In the last stage, social and conventional system role taking (children ten to twelve years of age), children can take the position of seeing another person's perspective as relating to the social group membership or social system within which they operate. Marketing implications of what Selman (1974) denoted are that a child's ability to understand persuasive intents occurs when he or she reaches eight to ten years of age, or the self-reflecting stage. Skills for thinking in more detail about advertiser tactics and motives probably increase when children reach the next stage, the mutual role-taking stage, age ten to twelve years, because it requires that children think about what an advertiser thinks about the audience's thinking. Finally, children ten to twelve may develop skills to understand different groups' perspectives (e.g., consumers, advertisers, retailers, and manufacturers.). Therefore, if children are capable of understanding advertisers' motives, they can also be skeptical of advertising because they are aware of their purposes. According to Selman's theory, children's skepticism toward television advertising would emerge when children are aware that the advertisement is intended to persuade them to buy the product. In addition, children might be aware that the advertiser's desires of making people buy their products could make the message biased (i.e., tell only good things about the product). 31.

(46) Consumer Socialization Researchers have tried to explain how people are socialized as consumers. Ward (1974) defined consumer socialization as "the process by which young people acquire skills, knowledge, and attitudes relevant to their functioning in the marketplace" (p. 380). Moschis (1987) viewed consumer socialization as an ongoing process that is useful to study consumers from a life-cycle approach. He defined consumer socialization as a lifelong process that explains how consumers learn to develop patterns of behavior and cognition (Moschis, 1987). In their socialization as consumers, children learn their consumer behavior through several means: observation, participation or incidental learning, and intentional instruction by parents, teachers, and other socialization agents (Moschis & Moore, 1979). Understanding children as consumers is crucial because attitudes, preferences, and loyalties for brands and behavior patterns that are established early in life can be carried over into adulthood and become a way of life (Guest, 1942,1945). Similarly, Ward (1974) wrote that, "at least some patterns of adult consumer behavior are influenced by childhood and adolescent experiences, and the study of these experiences should help us understand not only consumer behavior among young people, but the development of adult patterns of behavior as well" (p. 49). Understanding the process of how a child becomes a consumer is not an easy task. An integrative approach is needed that merges the different theoretical 32.

(47) contributions from cognitive development and marketing in a coherent framework. One theory that addresses this issue is the work of Roedder John (1999).. Children's Socialization as Consumers Roedder John (1999) integrated the cognitive and social theoretical perspectives on child development described earlier into a single framework called consumer socialization development to describe how children become adult consumers. When Roedder John (1999) integrated the stage theories of cognitive development, information-processing theories, and social development, a clearer picture emerged of the changes that take place as children become socialized into their roles as consumers (Roedder John, 1999). She hypothesized that these changes occur through perceptual, analytical, and reflective periods or stages of consumer development. Several outcomes of the socialization process are for example, children's advertising and persuasive knowledge, children's transaction knowledge, their decision-making skills and abilities, their purchase influence and negotiation strategies, and consumption motives and values (Roedder John, 1999). Roedder John (1999) considered these topics as socialization outcomes, connecting consumers' knowledge, values, and skills.. 33.

(48) Roedder John (1999) followed the same structural approach that Piaget followed, and her own earlier work (Roedder, 1981), to study children's knowledge. She proposed a series of stages to describe how children's advertising and persuasion knowledge evolve. The first is called the perceptual stage (from three to seven years of age). Here the focus is on children's perceptual thought. In this stage, children's consumer knowledge is related to observable features in the marketplace like brands and products, but exhibits what Piaget called "centration." This implies that children have brand or product familiarity but they center their perceptions on a single attribute or dimension of objects (e.g., flavor, size, or color). In this stage, children have constraints in encoding and organizing information, and information is rarely integrated beyond a superficial degree. A child's social perspective is also limited at this stage. Children are unable to take into account another person's perspective (i.e., egocentric thought). The analytical stage (from seven to eleven years of age) occurs when children progress to analyze information in a detailed manner. According to Roedder John (1999), this is the stage where the most important abilities in terms of consumer knowledge develop. Roedder John (1999) posited that the transition from perceptual to symbolic thought hypothesized by Piaget for children at these ages results in more sophisticated knowledge of the marketplace. Children are capable of understanding product categories by their underlying or functional dimensions, products are 34.

(49) perceived in terms of more than one attribute, and they are capable of generalizing from their product experiences. Additionally, in this stage children's reasoning becomes more abstract and enables them to process advertising motives; they can also think from the perspective of other socializing agents (e.g., parents, peers, and media). The reflective stage (from eleven to sixteen years of age) is related to even more complex and sophisticated processing skills. Roedder John (1999) pointed out that changes in this stage are more in terms of fine-tuning of the processes rather than major changes. Children are more aware of the social meaning of products, selfidentity and group expectations, and in general, all the social aspects required of consumers. In addition, children at this stage are aware of other people's perspectives. Rodder John's conceptualization of children' socialization process as consumers is a very important contribution because it summarizes relevant theoretical perspectives from the child development literature that shed some light on the process of children becoming consumers. However, Rodder's conceptualization does not include recent research in the development of children's attributions of mental states to themselves and others that might be useful for understanding in a deeper way the development of children's cognitive defenses, specifically skepticism toward advertising. For example, Young (2002) suggested that recent theoretical advances have overtaken debates in child psychology and they may have an impact on the debate 35.

(50) regarding when children are aware of commercial persuasive intent. This may have an impact by stimulating new research projects that incorporate the latest theoretical development on children's cognitive defenses, particularly children's skepticism toward advertising. Skepticism is considered an outcome of socialization within advertising and persuasive knowledge (Roedder John, 1999). Skepticism toward advertising is an important socialization outcome because it is associated with children's cognitive defenses (Bracks et al., 1988). Analyzing how children evolve from being egocentric to being socially aware is important because doing so sheds some light on the process of how children become skeptical adult consumers. One of the latest theoretical developments in child psychology is Theory of Mind. This theory explores how children attribute mental states to themselves and others. Theory of Mind could help us to understand when children are capable to attribute to others commercial persuasive intents.. Theory of Mind The Theory of mind is a perspective for studying how children's knowledge about the mental world develops. Flavell (2000) described "theory of mind" as an approach that investigates children's conceptions of "the most fundamental components of the mind, such as beliefs and desires, and children's knowledge of how these components affect and are affected by perceptual inputs and behavioral inputs" 36.

(51) (p. 15). Thus, theory of mind studies the emergence of children's everyday understanding of mental states (e.g., thoughts, beliefs, ideas, desires, etc.) and reasoning. Children have a theory of mind (Premack & Woodruff, 1978) when they attribute mental states to themselves and others. For example, Flavell (1999, 2000) described one common test in theory of mind research, a well-known false belief task, the "deceptive container" task. This task was intended to explore if young children know what a false belief is. An experimenter shows a child a candy box with pictures of candy on it and asks what the child thinks is in it. The usual response is "candy." Then the child gets to look inside and discovers that the box contains something else, crayons for example. The experimenter then asks the child what another child, who had not yet seen inside the box, would think it contained. Children five years old usually will say "candy," amused at the deception. Three-year-olds frequently answer that the child who had not yet seen inside the box will said "crayons." Theory of mind theorists presume that young preschoolers do not do well in the false belief task because they do not possess a mental representation of the mind. Consequently, young children do not understand that people can hold a false belief to be true, a mental representation that does not correspond to reality, and behave in accordance with it (Flavell, 2000). Thus, to hold a theory of mind (Premack and Woodruff, 1978), individuals attribute mental states to themselves and others. This is called "theory" because an 37.

(52) individual holds a system of inferences about non-observable states, and these inferences can be used to make predictions about the behavior of others. Thus, a person can infer, for example, intentions or purposes, beliefs, and thinking of other people (Flavell, 2000; Premack & Woodruff, 1978). Research revealed that young children (3- to 5-year olds) have more sophisticated reasoning about mental states of themselves and others than they were supposed to have (Wellman & Gelman, 1992). For example, Wellman and Gelman (1992) started to explore the idea of children's metacognition (cognitions about cognitions) as a theory of mind development. Flavell (2000) even suggested that the terms "theory of mind" and "metacognition" (from the child development literature) as synonyms when studying children's knowledge about mental phenomena. According to Flavell (1999, 2000) the development of theory-of-mind theory has produced several current explanations about how theory of mind works. For example, "theory theory" considers children's development as a kind of "informal scientific theory" about mental states. This approach suggests that experience plays an important role in children's progression toward an adult theory of mind. Similarly, "simulation theory," another approach described by Flavell (1999), emphasizes experiences of role taking as the main factor in fostering children's development of theory of mind. Emerging conception of the mind. 38.

(53) Child development researchers have mainly explored how theory of mind develops in young children. Flavell (1999,2000) reported studies which suggest that infants have some sense of when other people's actions are intentional and goal directed. For example, Flavell et al. (1992) reported that 5-year-olds have an emerging conception of the mind. This mental representation of the mind is what enables older preschoolers to understand the possibility of belief differences in physical facts, morality, social conventions, value, and ownership of property. On the contrary, 3year-olds have difficulty in attributing to others beliefs of all types, except ownership. Flavell (1999) also reported that children's knowledge about mental representations increases after the preschool period. He concluded, however, that it is not until middle childhood and later that children appear to have a substantial understanding that people's interpretations of an event may be influenced by their biases or expectations. Theory of Mind, persuasion knowledge, and marketplace social intelligence Theory of mind is a recent approach in child psychology from the 1980s and has only been sparsely incorporated in current research of children as consumers. Nevertheless, in an advertising context, it can be presumed that children may be aware of advertisers' motives and persuasive intent earlier than was considered by past research. Friestad and Wright's (1994) conceptualizations of persuasion knowledge are related to concepts in theory of mind. They proposed that persuasion knowledge is 39.

(54) based in an individual's beliefs about mental states and psychological processes that operate as mediators of persuasion or intentional social influence. Later, Wright (2002) introduced two concepts, marketplace metacognition and marketplace social intelligence. Both concepts are related to individuals' everyday cognitions about market thinking. Wright (2002) defined marketplace metacognition as "everyday individuals' thinking about market-related thinking" (p. 667) and marketplace social intelligence as "cognitive routines and contents dedicated to achieving marketplace efficacy..." (Wright, 2002 p. 667). An example of market-related thought could be children's negative evaluations of imitation products (metacognition: products or brands should not be copied). The learning of consumer scripts for having lunch in a fast food restaurant would be an example of marketplace social intelligence. Wright argued that these concepts are fundamental for answering questions regarding the way consumers come to understand beliefs, strategies, and intentions of marketing agents. He visualized consumers and marketers as playing mind games using metacognitive beliefs about the marketplace. Wright suggested that the human mind has evolved to cope with a complex social world. He borrowed the conception of domain-general and domain-specific processes from psychology and applied them in the marketing milieu. He suggested that the evolution of the human mind is related to a deep understanding of social 40.

(55) cooperation expressed in the form of cooperative exchange, semi-formalized in the marketplace. Marketplace knowledge is then considered as a sub-domain of social intelligence (Wright, 2002). He argued that consumer research should be more focused in the specific domain of marketplace social intelligence to examine the continuous interactions between consumers and marketers (Wright, 2000). Moreover, Wright (2000) proposed several topics that pertain directly to what he called "consumers' marketplace metacognitive social knowledge" (p. 679). Specifically, he proposed questioning how educational interventions, from the perspective of marketplace metacognition and social expertise, can best serve the developmental needs of young children, adolescents, young adults, and mature or elderly lay adults. Later, Wright (2000) added, "eventually we would like to be able to postulate a developmental model for the acquisition of knowledge about marketplace persuasion and influence" (p. 680). Wright (2002) argued that there is a lack of knowledge in the field about how young consumers acquire marketplace expertise, despite the fact that some research exists on how children acquire a theory of mind, children's oral persuasive communication practices, and children's socialization as consumers. The goal of this dissertation is related to the question that Wright posite pertaining to exploration of skepticism toward advertising in children. Skepticism toward advertising implies that children speculate and develop beliefs about marketing agents (i.e., advertisers). 41.

(56) These beliefs can be developed through their exposure to advertising and then be tested during their experience as consumers of diverse products. Disconfirmation of these beliefs would result in the development of skepticism in children. Friestad and Wright (1994) argued that children could understand persuasion as the strategic presentation of information when they have two abilities. The first is when children's conceptualization of beliefs, desires, imaging, and fantasies exist as separate mental states. The second is when they have the ability to realize that what occurs in a person's mind mediates how external information affects personal beliefs. However, little is known about when and how children meet these conditions to understand the persuasive intent and thereby develop cognitive defenses such as skepticism against advertising. Theory of Mind and deception research. Theory of mind has stimulated recent research in children's cognitive development in the areas of false beliefs, pretense, and deception from the child psychology perspective. Findings from these studies might shed some light on understanding how children develop persuasion knowledge and cognitive defenses. Research findings have shown that preschool children can understand deception when they master false belief understanding. Reviewing the findings about how and when young children act deceptively and understand deception may generate insights regarding the underlying processes in children's understanding of being skeptical of 42.

(57) other people' s motives or deceptive behavior. Piaget hypothesized that young children do not base their concepts of lying on the intention to deceive but they gradually acquire that conceptualization of lying over the 6 to 10 year-old age span. There are also consistent findings in the literature that indicate that this occurs at earlier ages (Rotenberg & Sullivan, 2003). There are several research streams related to deception. These include understanding of motives for deception (Webley & Burke, 1984), concealing information to influence other people's behavior (Peskin, 1992), deception in narratives (Peskin, 1996), detection of lies and cognitive cueing to manipulate information strategically (Chandler, Fritz, & Hala, 1989; Hala, Chandler, & Fritz, 1991; Wilson, Smith, & Ross, 2003), and children's family background to act deceptively (Cole & Mitchell, 1998). Findings reported in these studies are described briefly. Webley and Burke (1984) studied children with age ranges of 5 to 8 years to investigate the development of motives for deception. Children were given cartoon stories depicting situations involving altruistic deception (act deceptively to get a benefit for others) and self-centered deception (act deceptively to get a benefit for themselves). They found that self-centered deception was understood earlier than altruistic deception.. 43.

(58) Peskin (1996) pointed out that children's understanding of beliefs, motives, and values that regulate people's behavior is central in the development of their explanatory skills. Specifically, Peskin (1996) studied children's understanding of narratives in which the purpose of pretense is deception. Peskin (1996) defined deception as behavior intended to foster a false belief in another person to induce this person into error, and pretense as a mode of acting that separates the action from its normal cause and effect. Peskin (1996) argued that false belief understanding is an antecedent to understanding deception but not pretense. Both pretense and deception require an understanding of alternative realities. Her findings showed that children can understand pretense but cannot understand deception. Peskin (1996) attributed this sequence to the meta-representational requirements for understanding the counterfactuals that hold for mistaken belief but not for pretense. For example, in the classic tale of Little Red Ridinghood, understanding deception implies that the child thinks that Little Red Ridinghood thinks the wolf is her grandmother. On the other hand, the child understanding that the wolf is pretending to be the grandmother merely necessitates an understanding of pretense as acting-as-if. For young children, the psychological description of pretense may be something someone is doing (Peskin, 1996). Lillard (1996) considered that children have an early understanding of mental representation in pretense. She argued that pretense is what Vygotsky called a "zone of proximal development" for young 44.

(59) children because children who engage in more pretend role-playing have a better understanding of the mind than do other children. Peskin (1992) noted that children 5 years of age conceal information from a competitor who chose the object for which they had previously stated a preference. This implies that children have developed a representational understanding of the fact that to influence another's behavior, one must influence that person's mental state. Although the development of deception has not been fully explored, there is evidence that young preschoolers act deceptively explicitly or implicitly (Chandler et al, 1989; Hala et al., 1991; Peskin, 1992; Wilson et al., 2003). Wilson et al. (2003) found that children between 2 and 4 years of age intended to deceive others, or, at least, to have others act in accordance with their false statements rather than the truth, and that the vast majority of children's lies were self-serving. Parents recognize that their children lie from an early age and they tend to socialize them to believe that lying is unacceptable. Parents teach their children to tell the truth in different ways such as punishing liars for the transgression they committed, or challenging the veracity of their children's lies. These findings have important implications. First, the findings seem contradictory to Piaget's hypothesis that young children do not base their concepts of lying on the intention to deceive. Second, children may have learned to associate negative attitudes with deception at an early age. From a marketing perspective, the 45.

Figure

Documento similar

Government policy varies between nations and this guidance sets out the need for balanced decision-making about ways of working, and the ongoing safety considerations

Based on the preceding discussions, the study posits hypotheses and research questions in terms of four dependent variables of gender effects on mobile advertising

perspective, this study proposes that (a) adoption of ad blockers is positively influenced by the level of knowledge of their advantageous features; (b) the decision to continue

The functions of the television regulators in the Andean states (table 2), range from the promotion of good practices (Peru) and dialogue (Colombia) to regulation and control

However, it seems that they do feel that their work, the communication strategy based on consumer knowledge, and the media planning are very similar and related because

To respond to the main research question, which states whether “the implantation of on demand television in Spain has affected the high audiences in the ‘prime time’, time slot”

By using this filter, we considered the multiple parameters involved and avoid the simplification we will submit the sample to, if we had exclusively applied some of the

morronensis and the storksbills that serve as food plants for its larvae were considered in the main objectives of this study, which were: (1) to create