The use of an english spanish parallel corpus for the study of translation

Texto completo

(2) Hacemos constar que el presente trabajo fue realizado en la Universidad Central “Marta Abreu” de las Villas como parte de la culminación de los estudios de la especialidad de Lengua Inglesa con segunda lengua extranjera Francés, autorizando a que el mismo sea utilizado por la Institución para los fines que estime conveniente, tanto de forma parcial como total y que además no podrá ser presentado en eventos ni publicados sin autorización de la Universidad. _________________________ Firma de los Autores Los abajo firmantes certificamos que el presente trabajo ha sido realizado según acuerdo de la dirección de nuestro centro y el mismo cumple con los requisitos que debe tener un trabajo de esta envergadura referido a la temática señalada. ______________________ Firma del Tutor. ______________________ Firma del Jefe de Dpto. donde se defiende el trabajo. _____________________________________________________ Firma del Responsable de Información Científico-Técnica.

(3) To the person who always believed in me, to my Daddy Pirolo who would have liked to see this thesis through to the end. To my Mommy Martica, for loving me as her daughter, for being my teacher, for being the best mother ever. To my sisters, the most valuable treasure I’ve ever had. To my parents for their support. To my family for encouraging me to go ahead. To my boyfriend for enlightening my life with his love. To my friends for helping me to replace tears with smiles.. Dailenys.

(4) To my parents for having raised me and helped me get where I am today, for being my most devoted teachers. To Alain for coloring my life, for loving me no matter what, for our story. To my brother for being another father, for his help and advice. To Aunt Anita for the smiles and taking care of me. To Ani, my sister. To Mia and Pau, the best works I´ll ever bring to my life.. Mary.

(5) To Llanes, for being more than a Professor, our friend. To all our friends and classmates for all this time together. To our “profes” for what we know and what we will be able to obtain from that. To Li and her family for welcome me in their house and their hearts, for being a special friend. To Masio, for the good old days, because we finally fulfilled our dream.\ To my uncle Lilo for always being proud of me, for his trust. To Yane and Patri, for not forgetting the good times we have had.. Dailenys and Mary.

(6) ABSTRACT. ABSTRACT The general aim of the present research is to build a tool for the study of translation based on an English-Spanish parallel corpus as well as to assess its usefulness as an aid to systematize the study of translation and to achieve a higher translation competence by students in English Language Studies at the UCLV. This research provides empirical support for the teaching and learning of EnglishSpanish translation. The novelty of the research is that it is a contribution to English Language Studies translation subjects for the systematic study of translation using corpus linguistics. This is the first time that the issue of translation tools is tackled in the Department of English Studies at the UCLV. Internationally, there has been a lot of research in the area of computer-aided translation in general but less in the area of computer-aided translation study and training, as opposed to research and professional practice. For this reason our research may be a modest contribution to the field. From a theoretical perspective this dissertation contributes to the study of translation pedagogy in Cuba by delving into the conception and design of parallel corpora for didactic use. From a practical point of view the present research is important for the practice of translation because it may help to facilitate the study and practice of English-Spanish translation for students of English Language Studies using a bilingual corpus of texts. Key words: translation, parallel corpus, computer-aided translation, translation didactics.

(7) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1: Theoretical Approaches in Translation Studies and their Pedagogical Implications ........................................................................................ 6 1.1. Approaches to Translation Theory 6 1.1.1. The Linguistic Approaches 8 1.1.2. The Psycholinguistic-Cognitive Approaches 15 1.1.3. The Functionalist Approaches 18 1.2. Approaches to translation education 20 1.2.1. Linguistically motivated error-oriented and context-sensitive literalist approaches 21 1.2.2. The functionally and cognitively motivated text-oriented approach 23 1.3. Characterization of Current Teaching and Study Practice in English-Spanish Translation Courses in English Language Studies at the UCLV 27 1.3.1. Translation in curriculum C 27 1.3.2. Translation in Curriculum D 28 1.3.3. Observations concerning translation syllabi 29 Chapter 2: Computer and Translation Studies .................................................... 30 2.1. The use of computer assisted translation in professional translation training 30 2.2. Translation pedagogy and computer-aided translation 31 2.3. The use of corpora in Translation Studies 34 Chapter 3: Description and validation of a computer-based translation study aid tool .................................................................................................................... 40 3.1. Building the translation study aid tool 41 3.2. Evaluation of the application of the translation study aid tool by third-year English Language Studies students 49 3.2.1. Analysis of the Surveys 50 3.2.1.1 First Student Survey 50 3.2.1.2. Second Student Survey 52 3.2.1.3. Survey to the experts 53 Conclusions ........................................................................................................... 55 Recommendations ................................................................................................. 56 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 57 Appendix 1: Surveys to students ......................................................................... 61 Appendix 2: Survey to experts ............................................................................. 62 Appendix 3: Bibliographic reference for Science Journalism texts used in the corpus ..................................................................................................................... 62.

(8) INTRODUCTION. Introduction In Cuban universities where English Language Studies curricula include translation, the teaching of the subject is mainly conducted through the activity of translating texts. The instructor tells the students to find information on a topic which the whole class will deal with and in the next class the students are confronted with a new text that, as expected, deals with the field announced by the instructor. The students are told to read the text and discuss some of the main aspects presented in it. Then they are told to translate the first paragraph of the text into Spanish. Once they have finished their answers are checked by the instructor and commented upon by the class. After this they are expected to follow through with the other paragraphs. Thus goes on the typical translation class in our classrooms where a new text is translated every two weeks or so.. There´s nothing wrong with this approach except that. students have only translated some 40 texts by graduation time and that this number may not be enough for a full-fledged novice translator. What led us to work on the topic of this thesis is our dissatisfaction with the lack of systematic study and practice in the learning process in translation courses in our courses of study. By lack of systematicity we mean that the typical translation experience of students consists in coping with the specific translation problems in one text, problems that are seen and solved as unique cases and that are never again seen in other texts so that their solution is an individual, unique act rather than the application of a systematic procedure or technique. We believe that it is also good translation training to devote some time to study well-made translations so as to have greater translational experience even if we are not the actual translators. We think that a viable solution could be found in the study of ready-made translations in which certain translation problems could be systematically dealt with by students themselves with the help of some software that provided support to find the different equivalents in context and to be able to systematize knowledge about the typical solutions to translation problems. This could be accompanied by the establishment of debates with other students to make explicit the pros and cons of specific solutions. 1.

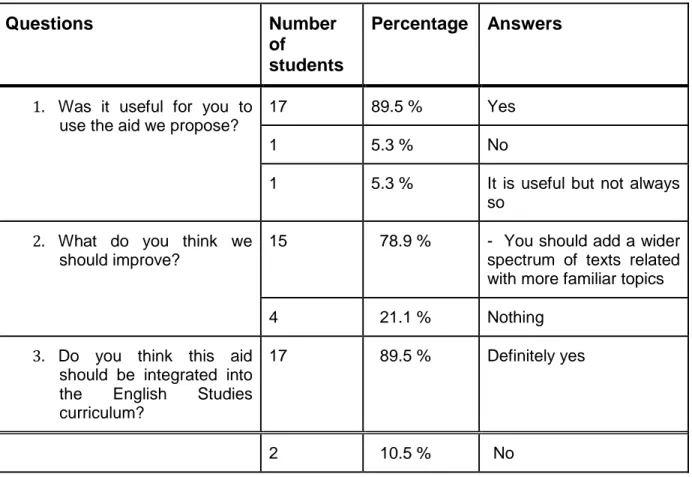

(9) INTRODUCTION. We believe that by using some of the technology associated with corpus linguistics we could be able to provide learners with the means for a more systematic study of translation problems and the solutions given by professional translators to these problems. Consequently, the previously described situation led to the following scientific problem: Will translation skills of English Language Studies students benefit from the use of a study aid based on an English-Spanish parallel corpus? Thus, the scientific object of this research is the development of the translation competence, and the field of action is the enhancement of English-Spanish translation skills of students enrolled in English Language Studies. The general aim of this research work is: To build a tool for the study of translation based on an English-Spanish parallel corpus and to assess its usefulness as an aid to systematize the study of translation and to improve translation skills in students of English Language Studies at the UCLV. And we advance the following hypothesis: English Language Studies students‘ translation skills will benefit from the use of a study aid based on an English-Spanish parallel corpus. The following scientific questions were answered throughout this research: . What are the theoretical and pedagogical bases that support the teaching and. learning process of English-Spanish translation with the help of computer-based study aids? . What is the current situation of the Translation teaching and learning process. in English Language Studies at the Central University ―Marta Abreu‖ of Las Villas? . What characteristics should a study aid tool based on a bilingual English-. Spanish corpus have in order to improve the teaching and learning process of Translation in English Language Studies? 2.

(10) INTRODUCTION. . What are the students‘ opinions about the study aid proposed?. . What are experts' opinions about the study aid proposed?. To answer the questions stated above, the following scientific tasks were accomplished: . Writing up the research design.. . Analyzing the available bibliography on this subject to determine the level of. knowledge and the current trends concerning the research topic. . Building the bilingual corpus.. . Designing aid tasks to use the corpus in the study of translation.. . Assigning these tasks to a group of English Language Studies third-year. students. . Designing the instruments to assess the efficacy of the proposed study aid.. . Applying surveys and interviews.. . Study and assessment of the obtained results.. . Writing the report of the Thesis.. Methods For the accomplishment of the previously mentioned tasks, different methods were used: Historical and logical method This method allowed us to analyze the evolution and the current situation faced by the discipline Translation Studies, which demands the use of computer-based tools and materials to support the teaching and learning process. Theoretical methods . Analysis and synthesis of the theoretical approaches to the topic. 3.

(11) INTRODUCTION. These methods were used to design and build the parallel corpus, the tasks and the instruments to measure its usefulness. . Inductive and deductive method. These methods were used to process the results obtained when applying the instruments, surveys and interviews and in the analysis of the bibliography. Empirical methods . Analysis of the content: in order to determine the characteristics of the texts. and their possible incidence on the translation process and the types of translation problems found in them. . Observation, interviews and surveys. Statistical and mathematical methods . Simple statistical analysis of the results from surveys and interviews. The sample chosen for the research involved 22 students enrolled in the third year of English Language Studies at the UCLV. To choose the sample, the aspects considered were: . The fact that these students have been through two semesters of training in. translation (Introduction to Translation Studies and Translation I) and that they still have five more semesters of English-Spanish Translation from the fourth year on. . The students´ willingness to actively participate in the research.. Expected Results This research provides an empirical support for the teaching and learning of EnglishSpanish translation. Its novelty lies in being a contribution to English Language Studies translation subjects for which it provides an aid for the systematic study of translated texts using corpus linguistics-inspired techniques. From a theoretical perspective this dissertation contributes to the study of translation by deepening into the conception and design of parallel corpora for its didactical use. From a practical point of view the present research is important for 4.

(12) INTRODUCTION. the practice of translation because it facilitates the study and practice of EnglishSpanish translation of the students of English Language Studies using a bilingual corpus of texts. The results of this research will be a helpful tool for translation teachers and professionals to solve practical and training problems. This thesis is divided into three chapters. Chapter 1 has to do with the theoretical approaches in Translation Studies and their pedagogical implications with emphasis in the comparative stylistics and interpretive approaches as we propose they should work together in the teaching and learning process of translation in English Language Studies. The chapter also discusses the different approaches to translation education that are related to the main theoretical approaches. Chapter 2 deals with Informatics in Translation Studies, translation didactics and computeraided translation, the theoretical bases for the use of computer-aided study tools in the translation learning process in the training of students of English Language Studies. It also discusses the characterization and evaluation of current teaching and study practice in English-Spanish translation courses in English Language Studies. Chapter 3 consists of the description of a computer-based translation study aid to improve the teaching and learning process of English-Spanish translation in English Language Studies, and of its validation by means of observation of its use by third-year students, their opinions collected through interviews and surveys; as well as the opinion of experts in the field of English-Spanish translation. Finally, the thesis includes conclusions, recommendations, bibliography and appendices.. 5.

(13) CHAPTER 1. Chapter 1: Theoretical Approaches in Translation Studies and their Pedagogical Implications 1.1. Approaches to Translation Theory Translation is almost as old as man himself. Ever since the dispersion of humankind from its original homeland in Africa brought about the differentiation of communication in early human communities and the emergence of different languages, contacts between these communities required the use of translation. Communication between speakers of different languages was required for trade and war alliances and translation in its earliest manifestation was related to these activities, and was performed by merchants, soldiers and slaves. With the emergence of writing, translation continued to be in close contact with the worlds of trade and war, but as knowledge accumulated in the form of written documents preserved in temples and libraries, translation was associated with the world of religion and scholarship. Priests and scholars had to learn ancient languages or command the contemporary language of other communities that were to be converted or that became sources of knowledge, and the new generations of those entering these professions had to be trained in their command of these languages, so that translation practice and translation teaching have been very close in their historical development. However, it was not until the second half of the Twentieth Century that Translation Studies became an independent academic field, and incorporated Translation Pedagogy as one of its components. Nowadays the study of this discipline has become of major interest not only to those specialized in the field of translation or linguistics but also to the least experienced who are on the process of acquiring the skills of interpreting and translating. One of the objectives of the new discipline is to establish a general translation theory as a guideline for the production of translations. However, throughout more than thirty years of Translation Studies, the result of the theoretical reflection has not been a general translation theory but a series of theories that, often, rival each other. 6.

(14) CHAPTER 1. Baker (2005: xiii) points out that Translation Studies is at a stage of its development when the plurality of contributions may lead some to give preference to some approaches and dismiss the rest. Indeed, from the marking out of the field of studies by Holmes, an increasing fragmentation of the theoretical studies has taken place, with a proliferation of the translation theories that reflect different linguistic paradigms, like in the case of the linguistic and functional theories, or the pragmatic and psycholinguistic theories, or the other fields of study as Relevance theory, Polisystem theory, Speech Act theory, the Feminist and the Cultural studies approaches, etc. Each of these theories offers a partial view of a complex field of study in which different disciplines are interconnected and which should be studied in an interdisciplinary or a multidisciplinary way due to its own nature. Nowadays theoretical thought has moved from the search for a general translation theory to the concept of translation as an Interdiscipline, whose study can represent the field of encounter of the different disciplines that make it up. Each individual theory can make an important contribution to the study of translation. According to Baker, more and more scholars are beginning to celebrate rather than resist the plurality of perspectives that characterizes the discipline and see the various frameworks available as essentially complementary rather than mutually exclusive. Concerning the opinion of a general translation theory, Marcella La Rocca (2003) considers not appropriate to take into account a unique translation theory because she thinks that this way the vision of the complexity of the translation activity would be lost. In her opinion it would be better to resort to different theories that share a consideration of translation as a communicative activity. Therefore this common core of translation as communicative activity constitutes ―the guiding principle‖ that allows unifying and integrating in a coherent way, the different translation theories and their points of view about the translation activity. This multiplicity of points of view will allow the production of different possible translations for each text and, at the same time, it will allow to find selection criteria among the different possible translations. 7.

(15) CHAPTER 1. In this section we will offer an overview of the approaches to translation beginning with Vinay and Darbelnet in the 1950‘s to Christiane Nord in the 1990‘s. The reader will notice that we dwell somewhat more extensively on the comparative stylistic approach and the interpretive approach since in English Language Studies in our country, the discipline of Translation favors the interpretive approach, and students are trained following the principles of this approach; whereas we firmly believe that students‘ translational skills can be improved if they also benefit from the application of some of the insights and practical techniques of comparative stylistics. Besides, we think that the comparative stylistics approach can be profitably related to the use of linguistic corpora, so that it would be easier for students to see what translation techniques professional translators use in their way from the source language to the target language, especially because they can have access to the originals in English and their translations into Spanish one next to the other on the same page. In our work we apply this principle in trying to put together the insights of a renewed comparative stylistics approach (use of techniques or shifts), with the psychological and cognitive processing highlighted by the interpretive approach, and the professional commitment of the functional approach. In the following we will briefly point out the main features of contemporary translation approaches by reference to the work of their original creators but also to reassessments of their work by more contemporary scholars.. 1.1.1. The Linguistic Approaches In the early 1950‘s and throughout the 1960‘s, Translation Studies was largely treated as a branch of applied linguistics, and indeed linguistics in general was seen as the main discipline which is capable of informing the study of translation. In the 1970‘s, and particularly during the 1980‘s, translation scholars began to draw more heavily on theoretical frameworks and methodologies borrowed from other disciplines,. including. psychology,. communication. theory,. literary. theory,. anthropology, philosophy and, more recently, cultural studies. There are now a 8.

(16) CHAPTER 1. number of distinct theoretical perspectives from which translation can be studied: linguistic. approaches,. psycholinguistic/cognitive. approaches,. interpretive. approaches, communicative/functional approaches, etc. The linguistic approaches have some common general notions in their conception of the translation process. First, they consider that translation‘s main determinant lies in the nature of the two language systems involved in the process. Second, they consider that the concept of equivalence is central to explain the relationship between translation and original. And third, they consider that the comparative description of the original and the translation can provide insights into the translation process which may be useful in translation training. These characteristics explain the reliance of these approaches on structural linguistics and particularly on such applied studies as contrastive analysis and comparative stylistics as conceived in the first three decades of the second half of the twentieth century. Contrastive analysis is the linguistic study of two languages, aiming to identify differences between them in general or in selected areas. Contrastive analysis may be restricted to the linguistic systems, but it may also be extended to include comparative stylistics and comparative rhetoric which place a greater emphasis on the contrastive study of texts and the textual resources in different languages. One of the most remarkable works in the field of comparative stylistics is that of Vinay and Darbelnet (1958), Stylistique comparée du français et de l'anglais, where they define a series of translation procedures. These authors propose seven basic procedures, classified into two groups: direct or literal, related to the most straightforward rendering of content from one language to another and oblique that has to do with more open and creative interpretation of content. Among the procedures proposed by these authors for the first type of translation (literal) are borrowing, calque, and literal translation. The second group (oblique translation) includes transposition, modulation, equivalence and adaptation. Vinay and Darbelnet also propose a series of additional procedures. Most of them, except compensation and inversion, are opposed pairs: dissolution opposed 9.

(17) CHAPTER 1. to concentration, amplification opposed to economy, expansion opposed to condensation, explicitation opposed to implicitation, generalization opposed to particularization, articulation opposed to juxtaposition, and grammaticalization opposed to lexicalization. According to José Luis Martí Ferriol (2006), Vinay and Darbelnet also made a list consisting of five steps a translator should follow when translating from the source language to the target language: . Identification of the translation units.. . Examination of the text in the source language, evaluating the. descriptive, affective and intellectual content of the units. . Reconstruction of the message‘s metalinguistic context.. . Evaluation of the stylistic effects.. . Generation and revision of the text in the target language.. Vinay and Darbelnet define the translation unit as the minimum segment of expression whose signs are joined in such a way that they should not be translated individually. At a practical level, the comparative stylistics approach is most useful in pointing out areas where direct translation of a term or phrase will not convey the intended meaning of the first language accurately in the second. At a global level, it leads the translator to look at broader issues such as whether the structure of the discourse for a given text-type is the same in both languages. The expansion of translation research in the 1960´s and 1970´s coincides with an increased awareness that it represents an emerging academic discipline. When Nida (1964) calls his theoretical works a ―science‖ of translation in his book Toward a Science of Translation, he is giving the topic a scholarly coherence and legitimacy that it has so far lacked. Nida distinguishes two different types of equivalence as formal equivalence (closest possible match of form and content between source language text and 10.

(18) CHAPTER 1. target language text) and dynamic equivalence (principle of equivalence of effect on reader of the target language text). His background lies in missionary bible translation, so he had to deal with languages that were very different from English. Therefore his key concept is that of dynamic equivalence, which evokes a receptor response that is substantially the same as that of the original receptors. This aim can be achieved by naturalness of expression, i.e. the translation should read like an original of the target language. Nida gives more priority to this equivalence of receptor response than any equivalence of form, which involves the need for the translator to apply certain techniques during the translation process. These techniques fall into three main categories: . additions (which may be incorporated into a translation only if they do not. change the semantic content of the message, but rather make information explicit that is implicitly present also in the source text), . subtractions (which make explicit information implicit without diminishing. the semantic content of the message), and . alterations (adjustments on the level of sounds, changes of grammatical. categories, changes in word class, word order, sentence type, or directness of discourse and semantic changes on the level of individual words) But translation theories that privilege equivalence had inevitably to come to terms with the existence of ―shifts‖ (term first introduced by Catford (1965)), between the foreign and translated texts, deviations that can occur in several linguistic levels and categories. J.C.Catford‘s 1965 study offers a precise description of grammatical and lexical shifts. He considers that translation should not be independent of linguistics because it is not a separate area of theorizing about language, but an area for applying linguistic theories. He affirms that translation equivalence occurs when a source-language and a target-language text or item share at least some of the same features of a relatively fixed range of linguistic characteristics, levels and categories, as well as a series of cultural situations.. 11.

(19) CHAPTER 1. Catford distinguishes formal correspondence, which exists between source and target categories that occupy approximately the same place in their respective systems, and translational equivalence, which exists between two portions of texts that are actually translations of each other. A shift has occurred when there are departures from formal correspondence between source and target texts, i. e. if translational equivalents are not formal correspondents. According to him, there are two major types of shifts: level shifts and category shifts. Level shifts are shifts between grammar and lexis, e. g. the translation of verbal aspect by means of an adverb or viceversa. Category shifts are subdivided into structure shifts (e. g. a change in clause structure), class shifts (e. g. a change in word class), unit shifts (e. g. translating a phrase with a clause), and intra-system shifts (e. g. a change in number even though the languages have the same number system). According to Lea Cyrus (2006), another important author in this field, one of the problems with Catford‘s approach is that it relies heavily on the structuralist notion of system and thus presupposes that it is practical to determine and compare the values of any two given linguistic items. She thinks that his account remains theoretical and it has never been applied to any actual translations. In spite of the fact that Nida spoke of a science of translating, his approach, like those of Vinay and Darbelnet and Catford, was included within a general conception of translation as part of applied linguistics. However, in 1972 James Holmes published a very influential paper, The Name and Nature of Translation Studies, in which he draws up a disciplinary map for Translation Studies, distinguishing ―pure‖ research-oriented areas of translation theory and description from ―applied‖ areas like translator training. His map of the discipline is now widely accepted.. 12.

(20) CHAPTER 1. Figure 1. Holmes‘s original proposal for Translation Studies. Mona Baker (2005) characterizes Holmes‘ contribution in the following way: Pure translation studies has the dual objective of describing translation phenomena as they occur and developing principles for describing and explaining such phenomena. The first objective falls within the remit of descriptive translation studies, and the second within the remit of translation theory, both being subdivisions of pure translation studies. Within descriptive translation studies, Holmes distinguishes between productoriented DTS (text-focused studies which attempt to describe existing translations), process-oriented DTS (studies which attempt to investigate the mental processes that take place in translation), and function-oriented DTS (studies which attempt to describe the function of translations in the recipient sociocultural context). Under the theoretical branch, or translation theory, he distinguishes between general translation theory and partial translation theories; the latter may be medium restricted (for example theories of human as opposed to machine translation or written translation as opposed to oral interpreting), area-restricted (i.e. restricted to specific linguistic or cultural groups), rank-restricted (dealing with specific linguistic ranks or levels), texttype restricted (for example theories of literary translation or Bible translation), timerestricted (dealing with translating texts from an older period as opposed to contemporary texts), or problem-restricted (for example theories dealing with the translation of metaphor or idioms).. Another approach that takes up the linguistic tradition within the new framework of Descriptive Translation Studies is that of Kitty van Leuven-Zwart (1989) and it is designed and used for the description of actual translations rather than of the relationship between two linguistic systems. In the approaches described so far, a translator should only revert to shifts or oblique procedures or techniques of adjustments if a more literal translation brought about some disadvantages with 13.

(21) CHAPTER 1. respect to the naturalness of the target text. Van Leuven-Zwart‘s view of shifts, however, is more neutral. She does not describe what translators could and should do or not, but simply observes and describes what they actually have done. To this end, she developed a two-part method for describing ―integral translations of fictional narrative texts‖, which consists of a detailed analysis of shifts on the microstructural level, i.e. within sentences, clauses, and phrases, and a subsequent investigation of their effect on the macrostructural level, i.e. ―on the level of the characters, events, time, place and other meaningful components of the text‖ (Van Leuven-Zwart, 1989). The early proponents of linguistic approaches had very different backgrounds – ranging from a didactic perspective (Vinay and Darbelnet, 1958) to missionary bible translation (Nida, 1964) to purely theoretical paradigms (Catford, 1965) – but they all had in common that they concentrated predominantly on the relationship between two languages and cultures rather than on the relationship between two actual texts. They all agreed that shifts cannot be avoided when transferring a message from one language to another and are indeed necessary to create a functionally equivalent and natural translation, but there tended to be a prescriptive undertone that a translator should only revert to shifts in cases where a closer translation would yield an unnatural result. Van Leuven-Zwart‘s approach, even though generally counted among the linguistic approaches, marks a transition towards a more neutral view of the phenomenon and a basically descriptive approach, which today has successfully replaced its theoretical and prescriptive precursors. But the advent of the computer helped to bring the concept of shifts back to the attention of researchers. Not only did the computer make it possible to overcome some of the drawbacks of van Leuven-Zwart‘s model, especially the marked difficulty of applying a complex model consistently across longer texts and of keeping track of the various shifts, it also opened up new areas of application in the fields of corpus and computational linguistics.. 14.

(22) CHAPTER 1. 1.1.2. The Psycholinguistic-Cognitive Approaches All the approaches we have considered so far have started from a mainly linguistic basis in trying to describe what happens during translation and have established relationships between source languages, cultures and texts with their target counterparts. But in the late 1970‘s the researchers at the Université de Paris interested in studying translation applied a more psycholinguistic and cognitive approach which was initially applied in the interpreter training by D. Seleskovitch and M. Lederer, and later transferred to translation training, particularly by the Canadian professor Jean Delisle. Thus, the Interpretive Approach, sometimes referred to as the interpretative approach, and also known as the theory of sense, as an approach to translating and interpreting adopted by members of the École Supérieure d´Interprétariat et de Traduction or Paris School, M. Lederer and D. Seleskovitch, shared the theoretical conceptions underpinning the teaching at this center. Initially developed in the late 1960´s on the basis of research in the field of interpretation, the interpretive theory of translation was subsequently extended to the written translation of non-literary or pragmatic texts (Delisle, 1980) and to the teaching of translation and interpreting. The main representative of the Paris School is Danica Seleskovitch. Drawing on her extensive professional experience in interpreting, she developed a theory based on the distinction between linguistic meaning and non-verbal sense, where nonverbal sense is defined in relation to a translating process which consists of three stages: interpretation of discourse, de-verbalization, and reformulation. Drawing on experimental psychology, neuropsychology, linguistics and genetic psychology, the work of the Paris School researchers focuses on the translating process, particularly on the nature of meaning as sense not as linguistic or verbal meaning. The resulting theory makes a distinction between the implicit (what the writer or speaker intends to say or means) and the explicit (what is actually said or written). Sense is composed of both, but full comprehension of sense depends on 15.

(23) CHAPTER 1. the existence of a sufficient level of shared knowledge between interlocutors, without which the confrontation between text and cognitive structures does not lead to the emergence of sense. Cognitive structures include either the cognitive baggage, or real world knowledge, and the cognitive context, which is the knowledge acquired through the specific and immediate reading of the text to be translated or interpreted. Ambiguity is, according to the theory of sense, a direct result of lack of relevant cognitive complements to verbal meaning. The possibility of multiple interpretations arises in situations in which only the surface or verbal meaning of the text is available and the translator does not have at his disposal all the cognitive elements and complementary information needed to extract sense. Interpreting is not based on verbal memory but on the appropriation of meaning, followed by reformulation in the target language. Translators, too, will reconstruct the meaning of the source language text and convey it to the readers of the translation. They will, however, normally go one step further than interpreters, by attempting to identify the expression of sense, to a certain extent, with the linguistic meanings of the source language. The translation process is seen not as a direct conversion of the linguistic meaning of the source language but as a conversion from the source language to sense and then an expression of sense in the target language. Translation is thus not seen as a linear transcoding operation but rather as a dynamic process of comprehension and re-expression of ideas. Jean Delisle, a Canadian scholar, developed a more detailed version of the interpretive approach to translation, based on discourse analysis and text linguistics, where the interpretation of the text is defined in terms of specific criteria such as contextual analysis and preserving textual organicity, with particular reference to the teaching of translation and interpreting. Delisle (1982) focuses on the intellectual process involved in translation, the cognitive process of interlingual transfer, and stresses the non-verbal stage of conceptualization. He views translation as a heuristic process of intelligent discourse analysis involving three stages: comprehension, reformulation and verification. 16.

(24) CHAPTER 1. In L’Analyse du discours comme méthode de traduction (1982), Delisle focuses on what he calls pragmatic texts, excluding literary texts because the latter have a predominantly expressive function. He proposes a hypothetical model of the translation process composed of the three distinct phases mentioned above. The first phase of the process is that of comprehension, essentially the task undertaken by a reader confronted with a new text, decoding its linguistic signs with reference to the language system and defining the conceptual content of the utterance by drawing on the referential context in which it is embedded. The second phase is the phase of reformulation or reexpression of the meanings identified in the initial analysis in a textual form appropriate to the TL (target language). It is this phase, the process leading to the discovery of "translation equivalents‖, that is the most complex and the most difficult to document. It is a dynamic process characterized by a continual back and forth movement between the information of the ST (source text) to be codified and the linguistic resources of the TL, in search of the ―closest natural equivalent‖ to the message of the source language in meaning and in style, to use Nida‘s expression. Reformulation reverbalizes the concepts of the source text by means of the signifiers of the other language based on reasoning, successive associations of thoughts and logical assumptions. The third and final phase of the process consists of verification, or justification. It is, in effect, a second interpretation, in which the translator reconsiders the intention of the original text with respect to his provisional solution as objectively as possible, in order to ensure that all of the relevant concepts of the ST have been represented in such a way as to be interpreted by the TL reader in the same way that they are understood by the SL (source language) reader. Verification may involve a process of back-translation to allow the translator to apply a qualitative analysis of selected solutions and equivalents with the purpose of confirming the accuracy of the final translation. This capacity of activating alternative construals from the working memory is evoked by J. Delisle‘s statement on the translator‘s creativity: Dès lors que traduire consiste à formuler un sens et non pas simplement à reproduire un agencement syntaxique de mots dotés de significations virtuelles, le 17.

(25) CHAPTER 1 contexte a pour effet de décupler les moyens linguistiques dont peut disposer le traducteur pour exprimer en langue d‘arrivée le sens du message original. C‘est un postulat de la textologie. Le traducteur jouit d‘une «liberté créatrice», au sens où l‘entend Alexandre Ljudskanov, qui le distingue du transcodeur. (Delisle, 1982). The ―theory of sense‖ must not be confused with Newmark‘s notion (1981) of interpretative translation, which requires a semantic method of translation combined with a high explanatory power, mainly in terms of the SL culture, with only a side glance at the TL reader. The interpretive approach advocated by members of the Paris school in fact argues the opposite of this position and places much emphasis on the target reader, on the clarity and intelligibility of the translation and its acceptability in the target culture in terms of writing conventions, use of idioms, etc., as well as the communicative function of oral or written discourse.. 1.1.3. The Functionalist Approaches Translation theory has begun to make more use of functional concepts of language. In the 1970‘s and 1980‘s, out of dissatisfaction with the predominantly prescriptive and decontextualized approaches at the time, functionalist ways of tackling the study of translation began to be proposed. Two particular schools of thought emerged, skopos theory and descriptivism. Skopos (Greek for ―goal‖) is a concept associated with the theory, which flourished in Germany, as an explicitly functionalist approach that views translating as goal-directed action. It makes much of the intended functions and likely effects of translations in comparison with the functions and effects of their originals, stressing that as a rule the two communication situations are not parallel. Reiss attempt to define the choices made by the translator according to the function of the TT (target text). Reiss divides translation types using Bühler‘s three linguistic functions; she distinguishes between the informative text, the expressive text and the operative text, each calling for particular sets of skills and strategies on the part of the translator (Mason, 1998). There can be no doubt that language functions have an influence on the translator´s task. It is important to distinguish between language function and text 18.

(26) CHAPTER 1. function. No actual text will exhibit only one language function. In fact all texts are multifunctional, even if one overall rhetorical purpose may be found. It is necessary to consider the function of the source text but also that of the translated text. The reasons for commissioning. a translation are independent of the reasons for the. creation of any particular source text. It is in this sense that the skopos theory of Reiss and Vermeer is to be understood. The function of the translated text, including the institutional factors surrounding the initiation of the translation, is a crucial determinant of translators' decisions. In this functional view of translation, any notion of equivalence between a source text and a target text is subordinate to the skopos, or purpose which the target text is intended to fulfill. Adequacy with regard to skopos then replaces equivalence as the standard for judging translations. The skopos concept can be used with respect to segments instead of whole texts, where this appears reasonable or necessary. This allows us to state that an action, and therefore a text does not have to be considered an indivisible whole. A source text is usually composed originally for a situation in the source culture and its status and the role of the translator in the process of intercultural communication depend on this situation. As its name implies, the source text is oriented towards, and is bound to, the source culture. The target text is oriented towards the target culture, and it is this which ultimately defines its adequacy. It therefore follows that source and target texts may diverge from each other quite considerably, not only in the formulation and distribution of the content but also as regards the goals which are set for each, and in terms of which the arrangement of the content is in fact determined. Even if a target text has the same function as its source text, the process is not merely a trans-coding, since according to a uniform theory of translation this TT is also primarily oriented, methodologically, towards a target culture situation or situations. When a translator considers that the form and function of a source text is basically adequate for the predetermined skopos in the target culture, we can speak of a degree of ―intertextual coherence‖ between target and source text.. For. instance, one legitimate skopos might be an exact imitation of the source text 19.

(27) CHAPTER 1. syntax, perhaps to provide target culture readers with information about this syntax. Or an exact imitation of the source text structure, in a literary translation, might serve to create a literary text in the target culture. Nord‗s (1991) division of translation types is based on the function of the TT. These divisions are documentary translation, such as word-for-word translation and literary translation, which serve as a document of a source culture communication between the author and the ST recipient, and instrumental translation, where the TT functions in its own independent right in the target culture. The communicative/functional perspective can be seen as an approach which relates the circumstances of the production of the source texts as a communicative event to the social circumstances of the act of translating and the goals which it aims to achieve.. 1.2. Approaches to translation education Although translation pedagogy has made remarkable advances in the 1990‘s there is still a lack of a comprehensive approaches to teaching translation. According to Sabaté (1999), ―since scientific investigation in this field is just beginning, the models developed recently are still tentative and require optimization.‖ A specific pedagogy of the subjects of translation needs to be developed, and therefore we have to find a theoretical model that can be applied to the pedagogy and to elaborate the methodology that guarantee the acquisition of the corresponding skills on the part of the students. Many translation scholars, like E. Nida, K. Reiss, C. Nord, P. Newmark, H.J. Vermeer, just to mention some of the great thinkers of this field, have taken this way to elaborate their theoretical models that have proved to be very practical in translation didactics. Sabaté (1999) studies several approaches to translation pedagogy some of which we will see in their association with the theoretical approaches we have reviewed above: 20.

(28) CHAPTER 1. 1. the linguistically motivated error-oriented approach and the contextsensitive literalist approach 2. the functionally motivated text-oriented approach and the new processoriented approach Although we are not in complete agreement with the features of the corresponding theoretical and pedagogical approaches that this researcher uses to name them, in general terms we will partially follow her characterization of these approaches. We will also follow this author in her characterization of what she calls the eclectic approach, which seems to be the one that provides the best framework for employing the tool we propose.. 1.2.1. Linguistically motivated error-oriented and context-sensitive literalist approaches The first group of pedagogical approaches that we will consider, following Sabaté, is the error-oriented approach, which is closely related to the use of error analysis as an instrument related to the contrastive linguistics research project of the 1950´s and the language typology studies. In this approach the emphasis is in the analysis of the product, not the process. The techniques of the comparative stylistics approach and the concept of shifts developed by Catford are useful in explaining what went amiss in a given translation and to provide adequate feedback to the student. However, translation exercises based on error analysis do not seem to bear enough scientific credibility and objectivity probably because there is little agreement among researchers and teachers on how to define and classify errors. In linguistics it is fairly common to define an error as a deviation from a certain norm, convention or a system of rules. In translation, because of the two languages involved in any translational process, errors may be linked either to the phase of text reception or to the phase of text production. Difficulties in translation do not only result from linguistic problems, they also depend on extralinguistic factors such as. 21.

(29) CHAPTER 1. knowledge of the source and target cultures, the stylistic, functional and pragmatic qualities required of the target text, the translation skopos. Sabaté points out that the concept of "error" generates in the student's mind negative connotations and therefore the teacher should try to minimize them, although the translation class should not be mainly devoted to ―error‖ correction. She also adds that apart from linguistic criteria, nonlinguistic criteria should also be included in the evaluation of the student's work because extralinguistic elements add an additional criterion for the teacher to account for what he considers an error and it helps students to better understand what the teacher would classify as an error. Also inspired in linguistic approaches to translation was the didactic proposal of Peter Newmark (Newmark, 1988), who propounded a theory of translation pedagogy focusing on the notion of text (the context-sensitive literalist approach, according to Sabaté). He suggests that translation is often to render the meaning of a text into another language in the way that the author intended the text to be understood. Newmark suggests the analysis—transfer—synthesis approach, whose first step is an analysis of the source text to show its structure. The second step (transfer) involves replacing source language words with target language words and making other adjustments for incompatibilities between languages. The third step (synthesis) involves making the target text more natural according to the target language. This approach is very pedagogical in that it sets out an explicit process that is easier for students to comprehend and implement. Newmark defines translation as the reproduction in the receptor language of the closest natural equivalent of the source-language message, first in terms of meaning and secondly in terms of style. This idealized definition of translation brings as a consequence a series of polar distinctions which force the translator to choose content as opposed to form, meaning as opposed to style, equivalence as opposed to identity, the closest equivalence as opposed to non-equivalence, and naturalness as opposed to formal correspondence. These decision-making processes carry the misleading underlying message of ideal, one-to-one and perfect matches between languages. 22.

(30) CHAPTER 1. Professional translators and scholars alike have demonstrated that translators do not first receive and analyze an SL text and then transfer it into the TL, but that the processes of reception and analysis operate according to the purpose of translation. The whole theory of Newmark revolves around the idea of equivalence and truth, which the translator should aim for. One of the implications of this principle is that the translator's task is somewhat an imperfect one, a highly discouraging thought for both translators and trainees.. 1.2.2. The functionally and cognitively motivated text-oriented approach The functional approach to translation theory is the framework for Christiane Nord´s text-oriented approach to translation pedagogy. Nord in 1991 designed a complete methodology based on text-analysis. Some fundamental aspects of the study are the theoretical, methodological and didactic aspects. The theoretical principles of the model of text analysis are based on an actionoriented concept of textuality and on a functional concept of translation. The translation of a text is an action which makes it possible that a new text fulfills certain functions for other participants in a new situation. Therefore, a translation is more than replacing certain linguistic elements of the source language by certain linguistic elements of the target language, it is the production of a functional target text maintaining a relationship with a given source text that is specified according to the translation skopos. Nord is against the equivalence-based concept of translation, but she acknowledges that, although this method does not correspond to the requirements of professional translation, it determines their translation activities in class. The methodological aspects include the analysis of both extratextual and intratextual factors, giving priority to the extratextual factors, which are analyzed first. This model involves the (retrospective) analysis of the source-text-in-situation, but 23.

(31) CHAPTER 1. also the (prospective) analysis of the target-text-in-situation, defined by the translation skopos. The model for text analysis is intended to guide the fundamental steps of the translation process; it points to the essential competences required of a translator, namely, competence of text reception and analysis, research competence, transfer competence, competence of text-production, competence of translation quality assessment and linguistic and cultural competence on the source and target languages. These competences have to be developed in the course of a training program for future professional translators and interpreters. In order to achieve these competences, Nord suggests the development of traditional translation exercises, in which the theoretical knowledge of methods and procedures is applied. However, Nord proposes the systematization of the teaching aims and brings them into a didactic progression which allows a reasonable and fair control of learning progress. The model developed by Nord comprises the essential factors and dimensions of the translation process and so she suggests finding out the priorities of a particular translation task, thus allowing a statistical approach for both teachers and students. She proposes an integrated and combined program outside the language departments, which may concentrate on translation problems which are bound to a particular pair of languages or cultures and on the development of linguistic and cultural competence. This approach to translation pedagogy is a very didactic one because it is based on a systematic implementation in the translation class. From the student's point of view, the analysis of extratextual and intratextual factors is very clear and educational. Nord's theory, however, is built on the basis that the communicative situation is the teachers‘ and students‘ main focus, whereas the linguistic structure of the text body is of secondary importance. This means that linguistic issues are not given the main priority and yet language-related problems arise all the time in students' translations. 24.

(32) CHAPTER 1. Nord's model is intended to prepare students to deal with any text-type, since it is based on the assumption that, as future translators, trainees need to be faced with both non-literary and literary texts. Sabaté‘s proposed pedagogical approach, the eclectic approach, benefits from the strengths of literalist, error-oriented, and text-oriented approaches to translation pedagogy and incorporates computerized tools to the trainees' translating task. This last feature is what makes it more attractive for the purpose of this thesis. The main rationale then behind the eclectic approach is that error-, text-oriented and other approaches can be used alternatively at different learning stages. Textanalysis may be a good way of initiating the student into the translation world, that is, on a preliminary stage of the student's training but error-analysis is a good way of fine-tuning the trainee's knowledge, that is, when the student is on a higher level. The main ideas extracted from previous approaches, and which are used in the design of the eclectic approach, are the following: 1. It is necessary to point out and classify linguistic errors (an error is considered as any target text output that goes against situational, contextual, linguistic and professional adequacy). 2. It is necessary to stress the importance of linguistic awareness and correctness (terminological, syntactical and text-typological correctness are taken into account). 3. It is necessary to emphasize the stage of text-analysis in the translation process. 4. It is necessary to acknowledge textual and extratextual factors considering that one very frequent source of errors is caused by the students' ignorance of the subject matter at hand (i.e. extratextual information) or a lack of world knowledge and experience. 5. It is necessary to focus on what goes on in the student's mind while translating because the students' output often fails to reflect the difficulties and doubts that they have come across before and during the translation process. 25.

(33) CHAPTER 1. 6. It is necessary to consider the students' changing needs during the learning stages and the fact that teachers must be able to identify what these needs are by assessing the students' progress. 7. It is necessary to acknowledge that computer-aided translation is a tool for human translation. For this reason the eclectic approach favors not only the use of machine translation but also the analysis of corpuses of target texts before doing the translation. The teaching of translation means enabling the participant to become aware of the problems of translating at the various levels and helping them to learn how to solve such problems, so that they become even better translators with time. This means that the teaching of translation requires a combination of practical teaching and theoretical research, which will enable trainees to develop their own translating skills. The approach to translation pedagogy Sabaté suggests covers the practical and theoretical areas which trainees need to develop for their future careers. The eclectic approach makes special emphasis on how important it is for teachers to develop the students' self-confidence by praising their successes over their failures. The eclectic approach proposes a six-step learning process of translation to help students tackle the source text and its translation more confidently and with more and better arguments to account for their decisions. The learning steps are: 1. Include specifications 2. Analyse the source text 3. Analyse corpuses of target texts 4. Do the translation 5. Analyse the translation 6. Test the student 26.

(34) CHAPTER 1. Therefore, rather than getting students to proceed following a linear structure (receive-analyze-transfer), they learn to approach the text from different angles and perceive the different factors existing in the translation such as linguistic, extralinguistic, pragmatic or professional.. 1.3. Characterization of Current Teaching and Study Practice in English-Spanish Translation Courses in English Language Studies at the UCLV The teaching of translation in higher education began in our country in the Faculty of Letters in the University of Havana. The purpose of the discipline Translation was always to train English-Spanish translators and to provide basic elements of Spanish-English translation. But the latter was only to be developed in professional practice according to the individual capacity of graduates. With the development of the Faculty of Foreign Languages at the University of Havana in 1980 the teaching of Translation has improved according to the advances of Linguistic Sciences, in general, and particularly in the field of Translation Studies, and with the objective of providing students with a general cultural and scientific basis, which would be more substantial and help the professional practice based on Marxist- Leninist theory of knowledge. In order to characterize the current teaching practice in translation subjects in English Language Studies it is necessary to refer to the syllabus of the discipline Translation and Interpretation and the corresponding subject syllabi for translation in the current and future curricula.. 1.3.1. Translation in Curriculum C In curriculum C, as the one current for 2nd to 5th year has been code-named, the translation subjects are Introduction to Translation, Translation I, II, III, IV, V, VI (all of which have 64 class hours each) and Computer-Assisted Translation with 32. 27.

(35) CHAPTER 1. class hours. Teaching is through a few conferences in Introduction to Translation and only practical classes in all the other subjects. All the subjects of the discipline share a common feature, which is the conception of translation as a process, which consists of various steps: a) Comprehension of the original text b) De-verbalization c) Elaboration of an equivalent text in the target language d) Confrontation of both texts e) Final checking of the text in the target language Texts are selected and presented according to the difficulty to translate them. The students should start from the simplest to the most difficult. The way of dealing with each of the texts in classes follows essentially the same activity progression, depending on the characteristics of the text to translate. The system of abilities is also the same:. to produce faithful, precise and high-quality translations. to use the basic, essential tools to translate. to apply the norms that rule the professional work of translation. to give solution to problems related to specialty languages in the reexpression of texts.. 1.3.2. Translation in Curriculum D In curriculum D there are seven subjects devoted to the field of translation: Introduction to Translation and Socio-Cultural Translation with 64 class hours each in third year; Scientific and Technical Translation, Official Documents Translation with 48 hours each and. Computer-Assisted Translation with 32 class hours in. fourth year, Socio-Economic Translation and Journalistic Translation with 48 class hours each in fifth year. These subjects are developed through a system of conferences and/or practical classes, depending of the characteristics of the subject and its content. 28.

(36) CHAPTER 1. 1.3.3. Observations concerning translation syllabi The characterization of the translation process in the translation syllabi so far reviewed leads to the conclusion that the prevailing didactic approach is based on the interpretive approach propounded by D. Seleskovitch and J. Delisle, although the subject Introduction to Translation provides an overview of techniques (shifts) there is no follow-up of this concept from the linguistics approaches of Vinay and Darbelnet, Catford and Van Leuven-Zwart.. 29.

(37) CHAPTER 2. Chapter 2: Computer and Translation Studies The information age has brought an explosion in the quantity and quality of information we are expected to master. This, along with the development of electronic modes for storing, retrieving, and manipulating that information, means that any discipline wishing to sustain itself in the twenty-first century must adapt its content and methods (Tymoczko, 1998). Translation Studies, of course, was not going to be the exception. Consequently, the translator‘s workplace has changed dramatically over the last twenty years or so, and nowadays the computer is undoubtedly the most important tool for a translator. Today, translators compose their texts on the computer, often receive their source texts in electronic format and sometimes their translations will only exist as digital information as in the case of web sites. The specific hardware and software resources individual translators will use vary depending on the task to be done. While in the case of most literary translators the translated text will probably take shape by means of a general purpose word processor, in the case of technical translators the target text will be produced with the help of the most sophisticated CAT (Computer-Aided Technology) tools.. 2.1. The use of computer assisted translation in professional translation training The new Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) as support for the professional translator include office automation, i.e. text, graphics and image processors, information retrieval systems, dictionaries and glossaries, terminological databases and other reference media in CD-ROM, databases made by the translator himself, machine translation and computer-assisted translation programs. The computer has accompanied, if not replaced, other tools in providing access to language and content information resources. Translation aids such as monolingual and bilingual dictionaries, terminologies and encyclopedias are now 30.

(38) CHAPTER 2. available not only on paper but also in electronic format. Colleagues, experts and newsgroups can now be consulted via e-mail, via telephone, fax and teleconferencing, besides face-to-face encounters. The storage capacity and processing power of personal computers have made access to linguistic and content information easier and quicker than ever before. There has been a revolution in the translator´s professional work because of Internet, which has opened up highways of communication and information retrieval. For example: the translator can get spellchecking and grammatical usage support from the functionalities included in his favorite word processor or use dictionaries and encyclopedias. When we use Internet, we can also consult mono-, bi- and multilingual dictionaries, machine translation programs and all kinds of reference archives or consult text corpora, for instance, to find the technical phraseology (collocations) that we do not usually see in terminological dictionaries. The translator´s work has become easier, on the one hand, thanks to web sites hosted by individuals and institutions, ranging from universities to international organizations and associations, which have become a way to access specialized glossaries, electronic dictionaries and reference. Now the problem is not finding a piece of information, but finding the right and reliable piece of information without wasting too much time.. 2.2. Translation pedagogy and computer-aided translation The use of ICT in translators´ training was preceded by CALL (Computer-Assisted Language Learning) that at the beginning was simply the use of the computer to support professors in their teaching activities and as a means for self-learning. The computer as a tool of the professional translator was first used in the second half of the 1980‘s in the curriculum of translators‘ and interpreters‘ training centers in Europe. There, subjects were taught that offered essentially training on operating systems and texts and graphics processors. In our own country at the Central University "Marta Abreu" of Las Villas, a similar subject, Introduction to Computing was included in the curriculum of English Language Studies in 1989, but it was not 31.

(39) CHAPTER 2. until almost ten years later, in the year 1998, when the subject Computer-Assisted Translation was included and started to be taught in 2002. We would like to point out the importance that ICT‘s have been gaining in training translators and interpreters. There are subjects devoted to informatics applied to translation, to documentation, to terminology (besides the use of off-line and on-line resources in translation classes), and there are also courses on translation and the new technologies. Lynne Bowker (2002) states in her book Computer-Aided Translation Technology: A Practical Introduction, ―Although advances in machine translation continue to be made, for the foreseeable future at least, human translators will still have a large role to play in the production of translated texts‖. CAT assists translators in their work but does not do the translation for them and therefore does not eliminate the human translator from the process. As our world becomes a more global society there is a greater need for translation and especially comprehensive but quick translation. In such a competitive marketplace, experience with CAT tools is becoming a necessary skill for translation students. Since there is increasingly more work for translators (such as translation of software and Web pages), the development of new translation technologies is, out of necessity, at an all-time high. The success of CAT tools relies on the continuous education of translators, the construction of user-friendly tools, the creation of electronic sources texts, and a close relationship between the tool developers and the translation training institutes. Translation technology can also facilitate translation research and generate data for future empirical investigations that were either impossible or difficult to conduct in the past. Electronic corpora and translation memories can provide large quantities of easily accessible data that can be used to study translation. Major research benefits include investigation of translation strategies and decisions (available through the use of bilingual parallel corpora) as well as the expanse of teaching practices for students through the comparison of archives of student translations. 32.

(40) CHAPTER 2. ―Translation-Memory Systems‖ are the most recent up-and-coming technology and are growing immensely in their popularity among translators. These systems connect the source and the target texts and store these parallels in a database. This permits the translator to use previously translated excerpts again in other points of the text. The TM system compares the new source text with prior translations. The matching of these excerpts can be exact matching, fully matching, fuzzy matching, term matching, or sub-segment matching. The use of this technology is limited to texts that are being updated, revised and have repetitive content. It also can be applied to series of texts in the same subject field. Professional translators working in the technical sector are perhaps more familiar with the parallel concordancing feature of translation memory systems. A translation memory is a data bank from which translators automatically retrieve fragments of past translations that match, totally or partially, a current segment to be translated, which must match, totally or partially, an already translated segment. But it can also be seen as a parallel corpus which translators manually query for parallel concordances of (already translated) specific terms or patterns. Aligned translation units are conveniently displayed on the screen, offering the translator a range of similar contexts from a corpus of past translations. A translation memory is, however, a very specific type of parallel corpus in that: a) it is ―proprietary‖: TMs are created individually or collectively around specific translation projects. They are highly specialized and very useful when used for the translation or localization of program updates. b) TMs tend to closure, to progressively standardize and restrict the range of linguistic options. This may be an advantage from the point of view of terminological consistency and of processing costs for clients or translation agency managers, but is often detrimental for readability (texts translated using a ―Workbench‖ can become very repetitive) and the translators eyesight (translators using a well-known Workbench often testify to a ―yellow-and blue-eye-syndrome). Translation workbenches and translation memories have indeed become the most successful technological product to be created for professional translators, but 33.

(41) CHAPTER 2. – as it often happens with MT (Machine Translation) products – their use is best limited to specific text types, such as online help files, manuals and all types of reference work which do not require sequential reading and for which the scope of translation can be limited to the sentence of phrase level (and thus left to a machine). When dealing with other types of texts translators are perhaps better off with a different kind of language resource, i.e. the type of corpora which are more familiar to lexicographers and linguists and which are only now beginning to enter the selection of tools available to professional and trainee translators.. 2.3. The use of corpora in Translation Studies Throughout the history of Translation Studies some trends have been developed in order to explain the successful practice of translation and to establish principles for practitioners. For these reasons we will make reference to one of the most promising current approaches to translation research, the corpus-based approach. Corpus Translation Studies (CTS) is central to the way Translation Studies will remain vital and will advance as a discipline. Corpus Translation Studies allow us, for example, to codify in compact and efficient forms, to have access and to interrogate enormous quantities of information - more information than any human being might collect to join or to examine in a productive life without electronic help. Also, the approach permits and promotes the construction of information fields that satisfy a new international, multicultural intellectualism, assuring the inclusion of information of small and big populations, of minority as well as majority languages and cultures. As big databases in the sciences, the corpora will be a heritage of the present to the future, allowing future research to construct on that of the present. This way, Corpus Translation Studies change in a qualitative and a quantitative way the content and methods of the discipline Translation Studies, in a way that fits with the modes of the information era. The potential of CTS to illuminate similarities and differences and to investigate in a manageable form the details of language-specific phenomena of many different 34.

Figure

Documento similar

Government policy varies between nations and this guidance sets out the need for balanced decision-making about ways of working, and the ongoing safety considerations

No obstante, como esta enfermedad afecta a cada persona de manera diferente, no todas las opciones de cuidado y tratamiento pueden ser apropiadas para cada individuo.. La forma

Therefore, the aim of this dissertation is to make a trilingual comparative study of the use of multimodal metaphor of the verbo-pictorial type in English, Spanish and

Another aspect of the “Buffyspeak” worth investigating in translation is the use of British English as opposed to American English since there are two British

A study is presented in this work to allow for the prediction of the radio coverage pattern of an AP, based on the local mean received power strength, while accounting for

These users can be common users of the Observatory’s public website (general audience), the graduates involved in the Observatory’s studies, the Spanish universities that

Additionally, we investigate the effects of Spanish morphology in English→Spanish Ngram-based translation modelling, showing that even though it is positive to reduce Spanish

The aim of this study is to carry out the process of translation and adaptation to Spanish of the locus of control in sport’s scale for children (Tsai and Hsieh, 2015) and to