The definition of "investmetnt" in the interplay between IIAs and the ICSID convention : revisting the double barrelled approach

Texto completo

(2) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 2 Universidad Externado de Colombia Facultad de Derecho. Rector:. Dr. Juan Carlos Henao Pérez. Secretaria General:. Dra. Martha Hinestrosa Rey. Decana:. Dra. Adriana Zapata Giraldo. Directora del Departamento de Derecho de los negocios:. Dra. Adriana Castro Pinzón. Director de tesis:. Dr. Nicolás Lozada Pimiento. Presidente de tesis:. Dr. José Vicente Guzmán Escobar. Examinadores:. Dr. Andrés Cárdenas Muñoz Dr. Maciej Zenkiewicz.

(3) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 3 Table of Contents. Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 5 Preliminary Remarks .......................................................................................................... 9 A.. Usual Anatomy of International Investment Agreements ....................................... 9. B.. Jurisdiction in ICSID Arbitration .......................................................................... 11. I.. The Search of an Additional Definition .................................................................... 16 A.. Objective Approach .............................................................................................. 17 1.. The Salini criteria as jurisdictional requirements ............................................. 17. 2.. Adjustments to the Salini criteria ...................................................................... 22. 3.. A different set of objective criteria ................................................................... 26. B.. Conceptual Approach: an Inherent and Abstract Meaning of “Investment”......... 34. C.. Brief Overview of Decisions Rendered During 2018 and 2019 ........................... 38. II.. A Cross-Reference to the Applicable IIA ................................................................. 40 A.. Plain Text Approach .............................................................................................. 42. B.. Object and Purpose of the IIA .............................................................................. 47. C.. The Non-Mandatory Application of the Salini Criteria ........................................ 51. D.. Brief Overview of Decisions Rendered During 2018 and 2019 ........................... 56. Concluding Remarks ......................................................................................................... 59 A.. Advantages and Disadvantages............................................................................. 60.

(4) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 4 1.. The search of an additional definition. ............................................................. 60. 2.. A cross-reference to the applicable IIA. ........................................................... 64. B.. Author’s Stance ..................................................................................................... 67 1.. A trend shift during 2018 and 2019. ................................................................. 68. 2.. Jurisdictional requirements beyond Article 25(1). ............................................ 70. 3.. The lack of consensus among arbitral tribunals: a contribution to the. fragmentation of international investment law ......................................................... 72 4.. A breach of State sovereignty ........................................................................... 73. 5.. The inexistence of binding precedent in international investment law and. arbitration .................................................................................................................. 74 C.. Conclusion ............................................................................................................ 76. References ......................................................................................................................... 77 Tables ................................................................................................................................ 85.

(5) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 5 Abstract This research paper addresses an issue that ICSID arbitral tribunals have encountered in the determination of jurisdiction ratione materiae in investment treaty disputes. The question is whether, due to the lack of a definition of “investment” in the ICSID Convention, a meaning of this term should be sought or, on the contrary, this term should be interpreted as a cross-reference to the definition provided by the applicable treaty. While commentators have referred to the former solution as a double-barrelled (or double keyhole) approach, this research paper suggests that there always is a double-test and, instead, the real difference is the search of an additional definition of “investment” to that provided by the applicable treaty. After giving a full context to this issue, this research paper describes and analyzes both approaches and holds a stance for the latter. Keywords: international investment law, international investment arbitration, foreign investment, investment, ICSID, ICSID Convention, ICSID arbitration, international investment agreements, IIAs, bilateral investment treaties, BITs, double-barrelled approach, jurisdiction ratione materiae, subject-matter jurisdiction..

(6) Running head: THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION. 6. The Definition of “Investment” in the Interplay Between IIAs and the ICSID Convention: Revisiting the Double-Barrelled Approach The notion of investment lies within the core of international investment law. Almost every international investment agreement (hereinafter referred to as “IIA”)1 provides a definition of this notion or, at least, enumerates the assets and operations considered as such to determine its scope of application. These definitions, in turn, offer arbitral tribunals one of the elements to determine jurisdiction over a given investment dispute. This notion is, thus, paramount in every investment dispute. However, the notion of “investment” was left undefined in the international convention that created the most important institution in international investment arbitration,2 the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (hereinafter referred to as “ICSID” or “the Centre”). Indeed, Article 25(1) of the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States (hereinafter referred to as “the ICSID Convention” or “the Convention”) grants jurisdiction to the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (hereinafter referred to as “ICSID” or “the Centre”) over “any legal dispute arising directly out of an investment”. The term “investment” is not defined by this or any other. 1. A brief presentation of IIAs will be made in the first paragraph of sub-section A in the preliminary remarks.. 2 According to the Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator of UNCTAD’s Investment Policy Hub, more than twice as many of the investment disputes that have been registered until the time of writing have been governed by the ICSID Convention and administered by ICSID, rather than other rules and institutions (UNCTAD, Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator. Available at: https://investmentpolicyhubold.unctad.org/ISDS/FilterByRulesAndInstitution). When the ICSID Convention is not chosen as the applicable lex arbitri, the UNCITRAL arbitration rules are usually chosen in the second place. These are the two most popularly chosen sets of procedural rules in international investment arbitration proceedings. Some other popular arbitration rules chosen in international investment arbitration are the ICC rules, the LCIA rules and the SCC rules..

(7) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 7 provision of the ICSID Convention and its related rules (Report of the Executive Directors, Institution Rules, Arbitration Rules, Conciliation Rules and Administrative and Financial Regulations3) either. This intentional omission4 to define the notion of investment in the ICSID Convention has led to a disparity among ICSID tribunals in investment treaty disputes. Indeed, on the one hand, most ICSID tribunals have addressed it by seeking a meaning of the term “investment” contained in Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention. However, on the other, some ICSID tribunals have deemed it as a cross-reference to the definition of investment provided by the applicable treaty. Authors and tribunals have usually referred to a double-barrelled (or double keyhole) approach5 in order to distinguish between tribunals that have taken the first approach and tribunals that have taken the second approach arguing that the former implies a double-test. However, it is doubtful that this reference describes adequately the aforementioned disparity among ICSID tribunals in investment treaty disputes because both approaches imply a double-test. Indeed, ICSID tribunals facing an investment treaty dispute must always verify whether those assets, transactions or operations qualify as such both under the applicable investment treaty, on the one hand, and under the ICSID Convention, on the other.. 3. For a brief description of these rules, see, e.g., DE NANTEUIL, A. (2017). Droit international de l’investissement. Second edition. Paris, France: Editions A. Pedone. ¶ 475. 4 According to the Report of the Executive Directors on the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes Between States and Nationals of Other States, the term “investment” was intentionally left undefined in order to leave the definition of “investment” to the consent of the Contracting States (¶¶ 26 and 27). Available at: http://icsidfiles.worldbank.org/icsid/icsid/staticfiles/basicdoc/partB-section05.htm#03. 5. See, i.e., NADAKAVUKAREN, K. (2016). International Investment Law. Text, Cases and Materials. Second edition. Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing. P. 83..

(8) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 8 The real difference between these approaches is the search of an additional definition of “investment” to that provided by (or resulting from the enumerated transactions protected by) the applicable treaty. Consequently, the distinction between tribunals that have sought a definition of the term “investment” outside of the applicable treaty and tribunals that have, instead, only referred to the relevant provisions of the applicable treaty might be more appropriate to describe the two approaches at the heart of this issue. Therefore, this research paper will address as “the search of an additional definition” (section I) what authors and tribunals have traditionally referred to as the double-barrelled approach and will address the opposite approach as “a cross-reference to the applicable IIA” (section II). Are both of these approaches equally appropriate to address the lack of a definition of the notion of investment in the ICSID Convention? Should any of them be preferred over the other? This research paper takes a stance for the latter. In order to do so, first, two preliminary remarks will be briefly addressed. Then, several decisions in which ICSID tribunals have encountered this issue will be analyzed: in the first section, decisions in which tribunals have sought an additional definition of “investment” and, in the second section, decisions in which tribunals have interpreted the lack of a definition as a cross-reference to the applicable IIA. To conclude, advantages and disadvantages of these approaches, as well as the author’s stance, will be presented..

(9) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 9 Preliminary Remarks The issue addressed by this research paper lies within the interplay between IIAs and the ICSID Convention. This means that this issue only arises in disputes where the basis of consent is an IIA and where the ICSID Convention and its related rules are applicable. Accordingly, only disputes where claims have been brought both under an IIA and the ICSID Convention are considered herein. This is why the usual content of international investment agreements (A) and the jurisdictional requirements in ICSID arbitration (B) will be succinctly described before explaining and analyzing each of the approaches ICSID tribunals have taken towards the lack of a definition of the notion of “investment” in the ICSID Convention. A.. Usual Anatomy of International Investment Agreements. The late 20th century witnessed a massive growth in the conclusion of international agreements for the promotion and reciprocal protection of investments, 6 also known as international investment agreements.7 These agreements are concluded mainly on a bilateral basis and, case in which they are usually referred to as bilateral investment treaties (hereinafter referred. 6. See, e.g., SORNARAJAH, Muthucumaraswamy. (2017). The International Law on Foreign Investment. Fourth edition. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 3 and 204; COLLINS, D. (2017). An Introduction to International Investment Law. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 1, 2 and 37; DE NANTEUIL, A. (2017). Droit international de l’investissement. Second edition. Paris, France: Editions A. Pedone. Pp. 45 and 50; and BISHOP, R., CRAWFORD, J., & REISMAN, W. (eds.). (2014). Foreign Investment Disputes. Cases, Materials and Commentary. Second edition. Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer International. Pp. 1-2. 7 BILLIET, Johan. (2016). International Investment Arbitration. A Practical Handbook. Antwerpen, Netherlands: Maklu-Publishers. P. 17; DE NANTEUIL, A. (2017). Droit international de l’investissement. Second edition. Paris, France: Editions A. Pedone. P. 93; NADAKAVUKAREN, K. (2016). International Investment Law. Text, Cases and Materials. Second edition. Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing. P. 1; and COLLINS, D. (2017). An Introduction to International Investment Law. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. P. 33..

(10) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 10 to as “BITs”).8 Some regional treaties — such as the United States Mexico Canada Agreement9 (hereinafter referred to as “USMCA”), the Transatlantic Trade Partnership (hereinafter referred to as “TTP”) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (hereinafter referred to as “TTIP”), as well as some sectoral agreements — such as the Energy Charter Treaty (hereinafter referred to as “ECT”) — contain investment protection provisions as well. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (hereinafter referred to as the “OECD”) even attempted to negotiate a Multilateral Agreement on Investment (hereinafter referred to as “MAI”). However, a final draft was never adopted.10 This phenomenon encouraged the development of a field in international economic law that was hitherto not so popular: international investment law. Certain issues exclusively related to these agreements, indeed, merit nowadays the attention of scholars, practitioners and companies worldwide. IIAs are usually divided into four parts: 11 a preamble, scope of application, substantive provisions and dispute-settlement provisions. First, the preamble sets forth the main purposes of the IIA. It is often referred to as a means to interpret the provisions contained in an IIA. The preamble is where usually extra-economic considerations are introduced as well (i.e., human rights, environment, rights of indigenous people, etc.).. 8 According to the Investment Policy Hub’s International Investment Agreement Navigator, there 2947 BITs at the time of writing, whereas there are only 377 treaties with investment provisions. Available at: http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/IIA 9 Formerly known as the North American Free Trade Agreement or NAFTA. 10. For a clear and brief presentation of IIAs, see: NADAKAVUKAREN, K. (2016). International Investment Law. Text, Cases and Materials. Second edition. Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing. P. 1; and COLLINS, D. (2017). An Introduction to International Investment Law. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 33 and 34. 11 See, e.g.: COLLINS, D. (2017). An Introduction to International Investment Law. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. P. 38; and DE NANTEUIL, A. (2017). Droit international de l’investissement. Second edition. Paris, France: Editions A. Pedone. P. 47..

(11) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 11 Second, the first provisions of an IIA usually define the persons and assets that will benefit of the treaty’s protections, as well as the time frame during which the provisions of the treaty will be applied. In other words, the first articles of an IIA usually define what the contracting parties have agreed to consider as protected “investors” and “investments” and the time during which they have agreed to do so. The combination of these provisions results in the material, personal and temporal scope of application of the IIA. Third, IIAs offer certain provisions that establish the rules regarding how the host State must treat investors and of the other contracting party and their investments (or, in other words, substantive provisions). The most usual substantive provisions contained in IIAs are: fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, guarantees against expropriation, protection against discriminatory and unreasonable treatment, most-favored-nation treatment, national treatment, adequate compensation and guarantees of free transfer of capital. Fourth, most IIAs provide dispute-settlement provisions. These provisions include Stateto-State Dispute Settlement provisions and investor-State dispute settlement provisions (hereinafter referred to as “ISDS”). Even though the most popular dispute-settlement mechanism among foreign investors is international arbitration, there are other investor-State dispute settlement mechanisms, such as conciliation and mediation. B.. Jurisdiction in ICSID Arbitration. Jurisdiction in international investment arbitration is determined both by the applicable IIA, investment contract or relevant national legislation and the set of procedural rules chosen by the claimant among the choices therein. 12 In other words, there are no universal jurisdictional. 12. See, e.g., BILLIET, Johan. (2016). International Investment Arbitration. A Practical Handbook. Antwerpen, Netherlands: Maklu-Publishers. P. 205: “Parties need to meet both the jurisdictional requirements provided in the BIT and the jurisdictional requirements under the selected procedural law”..

(12) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 12 requirements in international investment arbitration. Given that the scope of this research paper is limited to ICSID Arbitration, only the jurisdictional requirements in ICSID arbitration will be studied. Therefore, two types of arbitral proceedings fall out of the scope of the present research paper: on the one hand, arbitral proceedings carried out under other rules (such as the ICSID Additional Facility Rules, the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law – hereinafter referred to as “UNCITRAL” – Arbitration Rules, the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce – hereinafter referred to as “SCC” – Arbitration Rules or the London Court of International Arbitration – hereinafter referred to as “LCIA” – Arbitration Rules); on the other hand, ICSID arbitral proceedings brought under an arbitration agreement contained in a commercial or investment contract or a related submission agreement. ICSID arbitration jurisdictional requirements are set forth by Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention: The jurisdiction of the Centre shall extend to any legal dispute arising directly out of an investment, between a Contracting State (or any constituent subdivision or agency of a Contracting State designated to the Centre by that State) and a national of another Contracting State, which the parties to the dispute consent in writing to submit to the Centre. When the parties have given their consent, no party may withdraw its consent unilaterally. According to the opinion of several commentators, this article provides four jurisdictional requirements:13 jurisdiction ratione personae, jurisdiction ratione materiae, jurisdiction ratione temporis and jurisdiction ratione voluntatis.. 13. In this sense, see, e.g.: SCHREUER, Christoph H.; et al. (2009). The ICSID Convention: A Commentary. Second edition. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. P. 82; SORNARAJAH, Muthucumaraswamy. (2017). The International Law on Foreign Investment. Fourth edition. Cambridge, United.

(13) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 13 Jurisdiction ratione personae is also called personal jurisdiction and refers to the standing of the claimant to sue. In ICSID arbitration, this standing is provided only to those natural or juridical persons who qualify as “investors”, pursuant to the applicable IIA’s definition of “investor”. 14 Jurisdiction ratione temporis refers to a period of time prior to which the protections provided by the IIA are not applicable.15 Most IIAs provide a “scope of application” provision in which this period of time is usually set forth. For example, Article 11(1) of the Colombia-China BIT limits its scope of application to investments that existed at the time of its entry into force (as well as those made thereafter) and to disputes arisen after that same moment: This Agreement is applicable to existing investments at the time of its entry into force, as well as to investments made thereafter in the territory of a Contracting Party in accordance with the law of the latter by investors of the other Contracting Party. However, this Agreement only applies to disputes arisen after the Agreement enters into force. Jurisdiction ratione voluntatis refers to the consent given by the parties to the dispute for its submission to arbitration. 16 One of the distinguishing features of international investment arbitration may be found in this jurisdictional requirement, as the consent of the parties is reached somehow differently than in international commercial arbitration. Indeed, whereas consent to arbitration is usually given by the parties through the means of an arbitration agreement (i.e., an. Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 359 and 360; or BILLIET, Johan. (2016). International Investment Arbitration. A Practical Handbook. Antwerpen, Netherlands: Maklu-Publishers. Pp. 207 and 208. 14 See, e.g., DE NANTEUIL, A. (2017). Droit international de l’investissement. Second edition. Paris, France: Editions A. Pedone. Pp. 258-259 and 191-211. 15 See, e.g., Ibid., pp. 252 and 253. 16 BLACKABY, N., HUNTER, M., PARTASIDES, C., & REDFERN, A. (2015). Redfern and Hunter on International Arbitration. Sixth edition. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. P. 458..

(14) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 14 arbitration clause or a submission agreement), 17 in international investment arbitration the respondent-State may consent to arbitration in three ways: an arbitration agreement, its national legislation or an IIA. In the two latter, the respondent-State is said to give an offer to arbitrate, which the investor-claimant will accept by submitting a request for arbitration, consent to arbitrate being formed only in this very moment.18 It is with regard to the instrument in which consent to arbitration is given by the host State that an arbitral tribunal may determine jurisdiction ratione materiae.19 Finally, jurisdiction ratione materiae refers to the subject-matter of the dispute, which is why it is often referred to as subject-matter jurisdiction as well. The subject-matter that determines this jurisdictional requirement is the qualification of the claimant’s assets or operations as an investment. In investment treaty disputes before ICSID tribunals such qualification must be achieved both under the applicable IIA and the ICSID Convention. As mentioned earlier, IIAs usually provide a definition of (or enumeration of the assets and operations considered as) investments. Yet, as mentioned earlier as well, Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention does not define this term, leaving tribunals with the uncertainty of how to determine whether assets or operations qualify as such under the ICSID Convention. It is this uncertainty where the issue addressed by this research paper lies in. Unlike other rules (such as, for example, the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules), the ICSID Convention sets forth additional subject-matter jurisdictional requirements to the definition of. 17 18. Ibid., pp. 71 and 72.. For a brief, but clear and complete explanation of this hallmark characteristic of international investment arbitration, see, e.g., NADAKAVUKAREN, K. (2016). International Investment Law. Text, Cases and Materials. Second edition. Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing. Pp. 467-469. 19 DE NANTEUIL, A. (2017). Droit international de l’investissement. Second edition. Paris, France: Editions A. Pedone. P. 266..

(15) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 15 “investment” found in the applicable IIA. Indeed, according to Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention, only legal disputes that arise out directly from an investment will fall within ICSID jurisdiction. In other words, three subject-matter jurisdictional requirements must be fulfilled in ICSID Arbitration. This research paper analyzes an issue that concerns only one of them: the qualification of a given assets or operations as an investment..

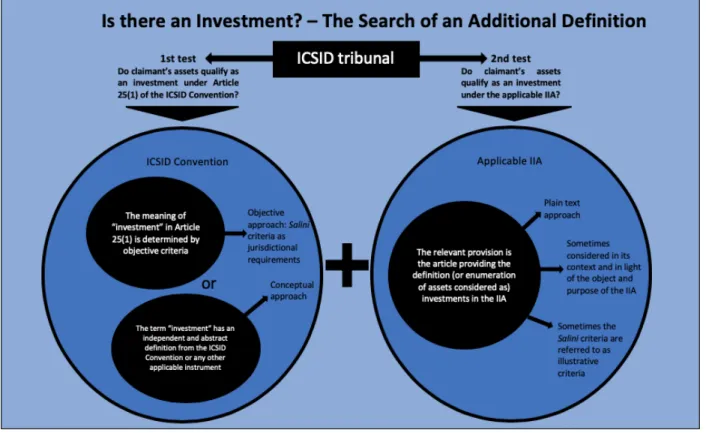

(16) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 16 I.. The Search of an Additional Definition Most ICSID tribunals have sought an additional definition of the term “investment” in. order to address the lack of a definition of this term in the ICSID Convention. However, the issue regarding where or how to find such a definition remains unsettled among them. While most arbitral tribunals have referred to different sets of objective criteria in order to ascertain a definition of the notion of “investment” in article 25(1), some others have attempted to find a general and abstract concept of investment (regardless of whether it is found in a BIT, the ICSID Convention or elsewhere).20 Thus, two methodologies are identifiable within the tribunals that have sought a definition of the term “investment” in Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention: an objective approach, which will be described in sub-section A; and a conceptual approach, which will be described in sub-section B. Sub-section C will examine how many tribunals have taken either of these approaches during 2018 and 2019 (until the time of writing). The reasoning of ICSID tribunals that have sought an additional definition of “investment” (with either the former or the latter methodology) is graphically represented in figure 1 below.. 20. A very brief and clear description of these approaches is made by the tribunals in Poštova banka v. Hellenic Republic (¶¶ 350 - 359) and in Romak v. Uzbekistan (¶¶ 197 - 206)..

(17) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 17. Figure 1. Graphic representation of the search of an additional definition of “investment” by ICSID tribunals A.. Objective Approach. While some ICSID tribunals have followed the approach taken by the tribunal in RFCC v. Morocco and Salini v. Morocco, applying what has become the so-called Salini test (1) – in most cases tailoring them to ascertain their own test (2) – , other ICSID tribunals have done so by referring to the criteria laid out by Profs. Christoph Schreuer, Loretta Malintoppi, August Reinisch and Anthony Sinclair in their commentary to the ICSID Convention (3). 1.. The Salini criteria as jurisdictional requirements. Even though nearly all authors have found the origin of the Salini criteria in the decision on jurisdiction rendered in Salini v. Morocco, these criteria were first mentioned (by the same tribunal) in RFCC v. Morocco. Thereafter, several tribunals have deemed the Salini criteria as.

(18) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 18 jurisdictional requirements set forth by Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention, as it will be shown below. Since most ICSID tribunals have tailored these criteria in order to ascertain their own test (as it will be shown in sub-section 2), this section will only examine the two cases in which the Salini criteria were first mentioned and two decisions in which they were applied as jurisdictional requirements as well (a decision on jurisdiction rendered shortly after the RFCC and Salini and an award rendered in 2018). In any case, as it will be further analyzed in sub-section C, tribunals have increasingly abandoned this approach in the last years. In its decision on jurisdiction, the tribunal in RFCC v. Morocco21 considered that the claims derived from an agreement concluded by the claimant and the Société Nationale des Autoroutes du Maroc22 had to qualify as an investment both in the sense of the applicable BIT and the ICSID Convention.23 In the tribunal’s view, the absence of a definition of “investment” in the ICSID Convention24 did not mean that the agreement of two contracting States in an IIA was enough to satisfy the jurisdictional requirements set forth by Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention. Accordingly, the tribunal agreed with commentators and previous ICSID tribunals according to which the requirement of an “investment” was an objective condition of ICSID jurisdiction. For this reason, the tribunal held that the objective conditions for any operation or asset to qualify as an investment under the ICSID Convention were, according to previous ICSID. 21. Consortium RFCC v. Kingdom of Morocco, ICSID Case No. ARB/00/6, Decision on Jurisdiction (July 16, 2001). Available (only in French) at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0225.pdf 22. Ibid., ¶ 42.. 23. Ibid., ¶¶ 50 and 51.. 24. Ibid., ¶ 59..

(19) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 19 tribunals and commentators, a contribution, certain duration, the participation in the risks entailed by the operation and a contribution to the economic development of the host State.25 The decision on jurisdiction in Salini v. Morocco was rendered fifteen days later.26 After acknowledging that Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention does not define the term “investment27 and that there had hitherto not been almost any cases in which this issue was addressed,28 the tribunal clarified that this did not mean that the existence of an investment was not an objective condition of ICSID’s jurisdiction.29 The tribunal thus proposed the objective criteria that every investment should satisfy in order to benefit access ICSID jurisdiction, appealing to scholarly opinions: The doctrine generally considers that investment infers: contributions, a certain duration of performance of the contract and a participation in the risks of the transaction (…). In reading the Convention's preamble, one may add the contribution to the economic development of the host State of the investment as an additional condition. 30 It is with regard to this quote that several international investment tribunals have spoken of a “Salini test”, made up of four criteria: financial contribution, certain duration, risk and contribution to the economic development of the host State.31 In other words, according to these. 25. Ibid, ¶ 60.. 26 Salini Construttori S.P.A. and Italstrade S.P.A. v. Kingdom of Morocco, ICSID case No. ARB/00/4, Decision on Jurisdiction (July 31, 2001). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/casedocuments/ita0738.pdf 27 Ibid., ¶51. 28 Ibid., ¶ 52. 29. Ibid., ¶52. Ibid., ¶52 as well. 31 See, e.g., SORNARAJAH, Muthucumaraswamy. (2017). The International Law on Foreign Investment. Fourth edition. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 362 and 363: “(…) In Salini, an attempt was made to identify the characteristics of an investment. The Salini test has often been followed by other arbitral 30.

(20) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 20 criteria, only where there has been a transfer of funds or a contribution of money or assets during a certain period of time, along with the assumption of associated risks, resulting in the contribution to the economic development of the host State, there will be an investment. It should be clarified from this point that nowhere in neither of the aforementioned decisions this tribunal said that the these criteria were mandatory nor that they should be applied in every case. It only asserted that commentators of the ICSID Convention generally considered that the term “investment” in article 25(1) inferred those four criteria. This tribunal actually even considered them to be interdependent and, thus, held that a weak presence of one of them in a given case could be compensated by a stronger presence of another (according to the interpretation of subsequent arbitral tribunals, such as the sole arbitrators in MHS v. Malaysia32 and Pantechniki v. Albania33). In spite of the previous observations, the authority of the Salini criteria among ICSID tribunals is undeniable. One of the first tribunals that applied the Salini criteria as jurisdictional requirements was the tribunal in Jan de Nul v. Egypt,34 in which the rights in dispute were the activities in connection with a dredging operation in the Suez Canal, the tribunal determined whether there was an investment or not with regard to both the meaning of the term “investment” in Article 25 of the ICSID Convention and under the applicable BIT. After adhering to ICSID. tribunals. It identified the characteristics of an investment as involving: contributions in money, in kind or in industry; long duration; the presence of risk; and the promotion of economic development”. 32 Malaysian Historical Salvors SDN, BDH v. The Government of Malaysia, ICSID Case No. ARB/05/10, Award on Jurisdiction (May 17, 2007), ¶ 70. Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/casedocuments/ita0496.pdf 33. Pantechniki S.A. Contractors & Engineers (Greece) v. The Republic of Albania, ICSID Case No. ARB/07/21, Award (July 30, 2009), ¶ 36. Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/casedocuments/ita0618.pdf 34 Jan de Nul N.V. and Dredging International N.V. v. The Arab Republic of Egypt, ICSID Case No. ARB/04/13, Decision on Jurisdiction (June 16, 2006). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/casedocuments/ita0439.pdf.

(21) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 21 tribunals that had previously relied on the Salini criteria to find the meaning of “investment” in the sense of the ICSID Convention, the tribunal clarified that these criteria could be “closely interrelated, should be examined in their totality and will normally depend on the circumstances of each case”.35 In spite of this clarification, this tribunal then analyzed whether the claimants’ operations in the Suez Canal satisfied all of the four Salini criteria, holding that they did. 36 Furthermore, since two BITs entered into force during the events that gave rise to the dispute and the proceedings, the tribunal held that the aforementioned activities qualified as investments under both of them.37 Less than a year prior to the time of writing, ICSID tribunals have continued to refer to the Salini criteria as jurisdictional requirements. The award rendered by the tribunal in Cortec v. Kenya38 is a good example. In this case, the tribunal had to determine whether, inter alia, a mining license was a protected investment in accordance with the UK-Kenya BIT and the ICSID Convention.39 Even though the tribunal asserted that the jurisdictional requirements provided by the ICSID Convention overlapped with those provided by the applicable BIT in this case,40 it held. 35. Ibid., ¶ 91.. 36. Ibid., ¶¶ 92 – 96.. 37. Ibid., ¶¶ 97 – 106.. 38 Cortec Mining Kenya Limited, Cortec (Pty) Limited and Stirling Capital Limited v. Republic of Kenya, ICSID Case No. ARB/15/29, Award (October 22, 2018). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10051.pdf. 39. Ibid., ¶ 2.. 40. Ibid., ¶ 259..

(22) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 22 that the alleged investments, although not protected, qualified as such on the ground that they satisfied all the elements of the Salini test.41 2.. Adjustments to the Salini criteria. The Salini criteria have not been uniformly applied by ICSID tribunals. Some ICSID tribunals have, indeed, modified them in several ways, as it will be shown below. These modifications have usually involved the contribution to the host State’s economic development criterion. Although less frequently, some tribunals have adjusted other of the Salini criteria (such as the contribution of resources by the investor). One tribunal even added more criteria to the test. The annulment committee in Mitchell v. Congo 42 modified the Salini criteria by giving one of them more importance than the others, considering that the contribution to the host State’s economic development was an essential characteristic of the notion of investment in the ICSID Convention. The assets in question were the immovable and movable property in which the claimant’s law offices operated, as well as his legal counseling activity.43 Since the notion of “investment” is undefined in the ICSID Convention, the committee deemed it necessary to look for its meaning in the applicable investment treaty and then verify whether if fitted the notion of investment in the ICSID Convention (which would prevail over the former), interpreting the latter in accordance with Article 31(1) of the VCLT.44 After pointing out that the parties had not arrived to any agreement concerning the definition of investment and that the applicable BIT contained an. 41. Ibid., ¶ 298 – 302.. 42 Mr. Patrick Mitchell v. Democratic Republic of the Congo, ICSID Case No. ARB/99/7, Decision on the Application for Annulment (November 1, 2006). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/casedocuments/ita0537.pdf 43. Ibid., ¶ 23.. 44. Ibid., ¶ 25..

(23) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 23 enumerative and non-exhaustive list of rights and assets considered as investments (instead of providing a definition),45 the committee approached the notion of investment relying on the Salini criteria, noting that ICSID case law and commentators had identified four characteristics of investments.46 Of these four criteria, the committee deemed that the contribution to the host State’s economic development was an essential criterion to determine whether an investment existed or not within the meaning of the ICISD Convention.47 Thus, it held that such an unusual operation as legal counseling should contribute to the economic development of the host State in order to qualify as a protected investment. 48 However, inasmuch as the tribunal failed to seek such a contribution, the committee held that it had manifestly exceeded its power (among other reasons).49 Besides modifying the fourth of the Salini criteria, the tribunal in Phoenix v. Czech Republic50 added two criteria to the traditional Salini test. At the origin of the dispute were found shares in several companies (which were entirely owned by the claimant).51 The tribunal had to determine whether these assets qualified as an investment under the Czech Republic-Israel BIT. In order to do so, this tribunal modified the fourth of the traditional Salini criteria (the contribution to the host State’s economic development) to a contribution to the host State’s economy,. 45. Ibid., ¶ 26.. 46. Ibid., ¶ 27.. 47. Ibid., ¶ 33.. 48. Ibid., ¶ 39.. 49. Ibid., ¶¶ 47 and 48.. 50. Phoenix Action, Ltd. v. The Czech Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/06/5, Award (April 15, 2009). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0668.pdf 51. Ibid., ¶ 2..

(24) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 24 considering that the traditional criterion was impossible to determine.52 Furthermore, by relying on general principles of international law, this tribunal added two more criteria to the Salini test:53 the accordance with the host State’s laws and good faith.54 In Saba Fakes v. Turkey, 55 the tribunal held that the notion of investment could be sufficiently defined with reference to only three criteria. This tribunal had to determine whether shares in a local telecommunications company that was put in receivership and subsequent sale by the Turkish government qualified as an investment or not under the ICSID Convention and the Netherlands-Turkey BIT.56 After summarizing how arbitral tribunals had hitherto approached the issue of defining the term “investment”,57 the tribunal considered that the notion of investment had an objective meaning within the ICSID Convention – besides the definition provided by the applicable BIT.58 Moreover, the tribunal only held that only the first three criteria of the Salini test were relevant to define an investment,59 considering that the “need for international cooperation for economic development” (as it appears in the preamble of the ICSID Convention) was an objective of the ICSID Convention rather than a criterion to define the notion of investment within the meaning of the ICSID Convention.60. 52. Ibid., ¶¶ 85 and 86.. 53. Ibid., ¶¶ 100 – 113.. 54. Ibid., ¶ 114.. 55 Mr. Saba Fakes v. Republic of Turkey, ICSID Case No. ARB/07/20, Award (July 14, 2010). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0314.pdf 56. Ibid., ¶¶ 30 and 31.. 57. Ibid., ¶¶ 98 – 106.. 58. Ibid., ¶¶ 108 and 109.. 59. Ibid., ¶ 110.. 60. Ibid., ¶ 111..

(25) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 25 Unlike the previous decisions, the originality of the award rendered in Malicorp v. Egypt61 lies within the emphasis given to the commitment of resources or financial contribution criterion. The dispute arose from the unlawful termination of a concession contract on a Build-OperateTransfer basis for the construction of an airport in Ras Sedr.62 Even though the parties did not discuss whether this contract could qualify as an investment or not,63 the tribunal addressed this issue in order to establish its jurisdiction over the dispute. The tribunal acknowledged that, in ICSID arbitration, any given operation must qualify as an investment both under the applicable BIT and the ICSID Convention. 64 Furthermore, it relied on the Salini criteria to ascertain the meaning of the notion of “investment” in Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention. However, it added the criterion of the nature to generate a profit to the traditional four Salini criteria. Despite this straightforward support of the Salini criteria, the tribunal clarified that the Salini criteria were not absolute and, instead, were merely an attempt to contour the meaning of the notion within the ICSID Convention.65 Accordingly, this tribunal’s interpretation of the Salini test is very original.66 Further than just adding an additional criterion to the test, the tribunal suggested that these definitions were complementary because each of them referred to different aspects of an investment: while the Salini’s definition referred to the contribution implied by an investment, the BIT’s definition referred to the assets or rights resulting from that contribution. Moreover, the tribunal asserted that. 61 Malicorp Limited v. The Arab Republic of Egypt, ICSID Case No. ARB/08/18, Award (February 7, 2011). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0499.pdf 62. Ibid., ¶ 93.. 63. Ibid., ¶ 102.. 64. Ibid., ¶ 107.. 65. Ibid., ¶ 109.. 66. Ibid., ¶ 110..

(26) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 26 all the definitions of “investment” ascertained by arbitral tribunals relying upon the Salini criteria emphasized on the contribution. This is why the tribunal based its holding on the BIT’s definition of investment and the Salini criteria (plus the “profit generation criterion”), with an emphasis on the “contribution” criterion. After determining that the conditions set forth by the relevant article of the applicable BIT were met,67 the tribunal analyzed whether the contract in question could be considered as a contribution in order to qualify as an investment within the meaning of “investment” resulting from the tribunal’s view of the Salini criteria. 68 Indeed, considering that the commitment resulting from the concession contract was a contribution, and further clarifying that the expenses engaged by the claimant during the preparation of the contract qualified as an investment due to the fact that it was signed (as opposed to cases in which state contracts have not been signed), the tribunal held that the dispute arose from an investment.69 3.. A different set of objective criteria. Some ICSID tribunals have referred to another set of objective criteria, sometimes explicitly and sometimes implicitly. These criteria were exposed by Professors Christoph Schreuer, Loretta Malintoppi, August Reinisch and Anthony Sinclair in their commentary to the ICSID Convention: It would not be realistic to attempt yet another definition of “investment” on the basis of ICSID’s experience. But it seems possible to identify certain features that are. 67. Ibid., ¶ 112.. 68. Ibid., ¶ 113.. 69. Ibid., ¶ 114..

(27) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 27 typical to most of the operations in question: the first such feature is that the projects have a certain duration. Even though some break down at an early stage, the expectation of a longer term relationship is clearly there. The second feature is a certain regularity of profit and return. A one-time lump sum agreement, while not impossible, would be untypical. Even where no profits are ever made, the expectation of return is present. The third feature is the assumption of risk usually by both sides. Risk is in part a function of duration and expectation of profit. The fourth typical feature is that the commitment is substantial. This aspect was very much on the drafters’ mind although it did not find entry into the Convention . . . The fifth feature is the operation’s significance for the host State’s development. This is not necessarily characteristic of investments in general. But the wording of the Preamble and the Executive Directors’ Report . . . suggest that development is part of the Convention’s object and purpose…70 These criteria are slightly different from the features referred to by the tribunal in RFCC v. Morocco and Salini v. Morocco. Indeed, instead of contributions, a certain duration, participation in the risks of the transactions and a contribution to the economic development of the host State, these authors refer to a substantial commitment, a certain duration, certain regularity of profit and return, the assumption of risk (usually by both parties) and a significance for the host State’s development. More precisely, the differences shown by this set of criteria are:. 70 See SCHREUER, Christoph H.; et al. (2009). The ICSID Convention: A Commentary. Second edition. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. P. 128..

(28) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 28 •. The requirement of a substantial commitment (which, while elevating the threshold, allows the interpreter to include not only contributions in money, but in kind or labor as well).. •. An additional criterion: the regularity of profit and return.. •. The bare requirement of a “significance” to the host State’s development. This feature might allow interpreters to require any given operation to contribute not only to economic development. Also, this feature has allowed tribunals to elevate the threshold of this “test”. For example, as it will be shown below, the sole arbitrator in MHS v. Malaysia held that the alleged investment did not qualify as such since it did not represent a significant contribution to the host State’s economic development.. Furthermore, these authors clearly excluded the possibility to interpret their commentary as implying that these features can be considered as jurisdictional requirements in ICSID arbitration. In their own words, “… these features should not necessarily be understood as jurisdictional requirements but merely as typical characteristics of investments under the Convention”.71 Nevertheless, several tribunals have referred to these criteria in order to determine whether a given operation qualifies or not as an investment under the ICSID Convention. As it will be shown below, while the tribunals in Joy Mining v. Egypt, MHS v. Malaysia and Unión Fenosa v. Egypt are clear examples of this approach, the tribunal in UAB Energija v. Latvia referred to this. 71. See SCHREUER, Christoph H.; et al. (2009). The ICSID Convention: A Commentary. Second edition. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. P. 128..

(29) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 29 set of objective criteria (but asserted they were not jurisdictional requirements and, thus, it applied them non-mandatorily). The tribunal in Joy Mining v. Egypt72 did not rely on the decision on jurisdiction rendered in Salini v. Morocco. This tribunal had to determine whether bank guarantees issued in favor of the claimant could qualify as investments.73 In order to do so, the tribunal first analyzed the claim under Article I (a) (i) and (iii) of the UK-Egypt BIT.74 After concluding they did not qualify as such under these provisions, the tribunal then turned to the claim’s analysis in the light of the ICSID Convention. It first noted that the lack of a definition of the notion of “investment” in the Convention did not mean that any operation, asset or transaction agreed by the contracting parties of a BIT could qualify as such thereunder. 75 Consequently, the tribunal deemed that the bank guarantees had to meet the “objective requirements of Article 25 of the ICSID Convention”.76 Referring to several ICSID awards and decisions as well as to commentators, 77 the tribunal asserted that a project would meet such requirements if it entailed “a certain duration, a regularity of profit and return, an element of risk, a substantial commitment and […] constitute a contribution to the host State’s development”.78 Although the tribunal did not mention it explicitly, these criteria are the same criteria exposed by. 72. Joy Mining Machinery Limited v. The Arab Republic of Egypt, ICSID Case No. ARB/03/11, Award on Jurisdiction (August 6, 2004). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0441.pdf 73. Ibid., ¶ 42.. 74. Ibid., ¶¶ 43 – 47.. 75. Ibid., ¶ 49.. 76. Ibid., ¶ 50.. 77. Ibid., ¶¶ 51 and 52.. 78. Ibid., ¶ 53..

(30) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 30 the aforementioned authors in their commentary to the ICSID Convention. After, among other considerations, demonstrating that these requirements were not fulfilled by the operation in question,79 the tribunal held it lacked jurisdiction ratione materiae as the claim fell both out of the applicable BIT and the ICSID Convention. The sole arbitrator in MHS v. Malaysia80 reasoned similarly. The rights in dispute were those derived from a contract entered into by the claimant for the location and salvage operation of a sunken vessel with the Malaysian government. 81 Unlike the tribunal in Joy Mining v. Egypt, he referred explicitly to the features mentioned by Prof. Christoph Schreuer in his Commentary to the ICSID Convention.82 The sole arbitrator analyzed seven cases which, in his view, were relevant in the analysis of the issue. 83 He identified two different approaches among these tribunals: a Typical Characteristics Approach and a Jurisdictional Approach. 84 However, after analyzing these approaches and these cases, the sole arbitrator concluded that this dichotomy was irrelevant for the finding of the tribunal because both of them granted the possibility to place a stronger emphasis on one or other of the hallmarks of “investment” depending on the facts of each case.85. 79. Ibid., ¶¶ 55 – 57.. 80. Malaysian Historical Salvors SDN, BDH v. The Government of Malaysia, ICSID Case No. ARB/05/10, Award on Jurisdiction (May 17, 2007). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/casedocuments/ita0496.pdf 81. Ibid., ¶¶ 7 – 11.. 82. Ibid., ¶ 44.. 83. Ibid., ¶ 69 – 104.. 84. Ibid., ¶ 70.. 85. Ibid., ¶ 105..

(31) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 31 Accordingly, the sole arbitrator in this case deemed reasonable to require or not a stronger or weaker presence of any of the hallmarks of investment depending on the facts of the case and considering them globally.86 This is why, turning to the analysis of the case, in light of the weak risks and durations involved, the sole arbitrator held that the contract should represent a significant contribution for the economic development of the host State, elevating the threshold to consider this criterion was met.87 Given that it did not,88 the sole arbitrator held that the contract in question could not qualify as an investment within the meaning of the ICSID Convention.89 In UAB v. Latvia, 90 the claimants’ investments were shares in a local company, some financial operations and the know-how and expertise in heating services as well as the operational management expertise. 91 After analyzing whether these assets could be considered protected investments under the applicable BIT,92 the tribunal analyzed whether a legal dispute arose out of an investment under Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention. The claimant submitted that the aforementioned assets qualified as investments under Article 25(1) as understood by Prof. Christoph Schreuer’s in his Commentary to the ICSID Convention.93 In the tribunal’s view, these features could not be considered jurisdictional requirements, but were met in the case at hand.94. 86. Ibid., ¶ 107.. 87. Ibid., ¶ 124.. 88. Ibid., ¶ 143.. 89 However, the claimants applied for annulment of this award and, in its decision (which will be reviewed in section II), the ad hoc committee held an opposite stance regarding the hallmarks of an investment. 90. UAB E energija (Lithuania). v. Republic of Latvia, ICSID Case No. ARB/12/33, Award (Decemeber 22, 2017). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw9481.pdf 91. Ibid., ¶ 521.. 92. Ibid., ¶¶ 519 – 524.. 93. Ibid., ¶ 525.. 94. Ibid., ¶ 526..

(32) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 32 Accordingly, after demonstrating they were met,95 the tribunal concluded that the assets in question qualified as investments under Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention. 96 In other words, this tribunal addressed the lack of a definition of the notion of “investment” in the ICSID Convention by referring to the features mentioned by Prof. Christroph Schreuer without, however, deeming them as jurisdictional requirements. Finally, as the sole arbitrator in Malicorp v. Egypt, the tribunal in Unión Fenosa Gas, S.A. v. Egypt97 referred implicitly to this set of objective criteria. The claimant argued that the resulting rights from a natural gas sale and purchase agreement and the shares in a local company were protected investments both under the Spain-Egypt BIT and Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention.98 The tribunal asserted that, if these assets qualified as “investments” under the BIT, they would qualify as such under the ICSID Convention as well. However, it immediately clarified that both of these provisions included, as part of a same test, a holistic approach and the “indicia” of an investment mentioned by the tribunal in Salini v. Morocco.99 In other words, even though this tribunal considered that the applicable BIT and the ICSID Convention provided the same single test, both of them included the Salini criteria. Furthermore, it relied on a different set of criteria (although without distinguishing them from the Salini criteria). Indeed, the tribunal replaced the “contribution” criterion with a “profit and return” criterion and the “contribution to. 95. Ibid., ¶ 527.. 96. Ibid., ¶ 528.. 97. Unión Fenosa Gas, S.A. v. Arab Republic of Egypt, ICSID Case No. ARB/14/4, Award (August 31, 2018). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10061.pdf 98. Ibid., ¶ 6.64.. 99. Ibid., ¶ 6.4..

(33) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 33 the economic development of the host State” criterion with a “commitment to development of Egypt’s economy” criterion.100. 100. Ibid., ¶ 6.66..

(34) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 34 B.. Conceptual Approach: an Inherent and Abstract Meaning of “Investment”. In the awards analyzed in sub-section A, tribunals compare the operations, transactions or assets claimed as investments against a set of criteria or elements (such as the Salini criteria or one of its variations) in order to determine whether the former qualify as such under the ICSID Convention. The present section will analyze awards in which tribunals have, instead, relied on an abstract or inherent definition of the notion of investment. This approach must be distinguished from the objective approach at least in two aspects. First, its objective is to find a meaning of the notion of investment that serves as a point of reference in any investment dispute (whether it is a treaty-based dispute or a contract dispute, under the ICSID Convention or otherwise). Second, this approach does not rely on a checklist that has or might vary according to the opinion of any arbitral tribunal. Four decisions in which arbitral tribunals have taken this approach are mentioned below. In CSOB v. Slovakia,101 the tribunal had to determine whether a loan granted to a Slovak company under an agreement to facilitate the privatization of CSOB both in the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic102 (the payment of which was secured by the Ministry of Finance of the Slovak Republic103) qualified as an investment or not. After acknowledging that Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention prevailed over the definition of “investment” provided by the UK-Slovakia BIT, the tribunal asserted that a double-test was required to establish subject-matter jurisdiction. 101 Československa Obchodni Banka, A.S. v. The Slovak Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/97/4, Decision of the Tribunal on Objections to Jurisdiction (May 24, 1999). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0144.pdf 102. Ibid., ¶ 2.. 103. Ibid., ¶ 3..

(35) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 35 over the dispute.104 Thus, the tribunal first deemed that the loan at the origin of the dispute qualified as an investment under the UK-Slovakia BIT. 105 Second, and more importantly, the tribunal considered that the loan qualified as an investment under Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention106 relying on the definition of “investment” suggested by the respondent in its submissions (“the acquisition of property or assets through the expenditure of resources by one party – the “investor” – in the territory of a foreign country – the “host State” –, which is expected to produce a benefit on both sides and to offer a return in the future, subject to the uncertainties of the risk involved”).107 However, the tribunal clarified that the elements of this definition were usually present in transactions that could be considered investments, but not prerequisites to consider any transaction as such. The sole arbitrator in Pantechniki v. Albania,108 Professor Jan Paulsson, did not suggest his own definition of investment either. Instead, he relied on an academic definition of the notion of “investment.” The assets at stake in this case were the equipment and materials used for the construction of a road in Albania.109 After acknowledging that these assets appeared to qualify as an investment under the Albania-Greece BIT, he pointed out the difficulty of doing so under the ICSID Convention as it lacked a definition of the notion of “investment. 110 However, Prof.. 104. Ibid., ¶ 68.. 105. Ibid., ¶ 89.. 106. Ibid., ¶ 88.. 107. Ibid., ¶ 90.. 108. Pantechniki S.A. Contractors & Engineers (Greece) v. The Republic of Albania, ICSID Case No. ARB/07/21, Award (July 30, 2009). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/casedocuments/ita0618.pdf 109. Ibid., ¶¶ 12 and 13.. 110. Ibid., ¶ 35..

(36) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 36 Paulsson considered that the Salini criteria gave an a inappropriately wide margin of appreciation to arbitral tribunals.111 Therefore, he suggested that the most reasonable solution was to arrive to a common understanding of an inherent definition of the notion of “investment”112 and relied on the definition given by Professor Zachary Douglas in his textbook, The International law of Investment Claims (2009), as an example: “the economic materialization of an investment requires the commitment of resources to the economy of the host State by the claimant entailing an assumption of risk in expectation of a commercial return”.113 The tribunal in Romak v. Uzbekistan114 considered that the notion of “investment” had an intrinsic meaning as well. In this case, the assets in dispute were claims to money and rights arising out of a wheat supply contract and a previous arbitral award.115 The tribunal straightforwardly refused to simply confirm that the claimant’s assets fell within one or more of the categories listed in the article that defined investment, as the claimant suggested, because that would deprive the term “investments” of an inherent meaning. 116 In the tribunal’s view, indeed, the notion of “investment” had an independent meaning from the enumeration provided by the SwitzerlandUzbekistan BIT.117 It also refused to sponsor the claimant’s submission that the term in question was broader under the UNCITRAL rules than under the ICSID Convention. 118 The tribunal. 111. Ibid., ¶ 36.. 112. Ibid., ¶ 46.. 113. Ibid., ¶ 36 and 47.. 114. Romak S.A. (Switzerland) v. The Republic of Uzbekistan, UNCITRAL, PCA Case No. AA280, Award (November 26, 2009). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0716.pdf 115 Ibid., ¶ 178. 116. Ibid., ¶ 180.. 117. Ibid., ¶ 188.. 118. Ibid., ¶¶ 193 and 194..

(37) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 37 summarized the various approaches given by ICSID tribunals to the definition of “investment” in order to explain its subsequent reasoning.119 Indeed, instead of relying on one of these approaches, the tribunal relied on the ordinary meaning of the term “investment,” interpreting it accordingly with the Switzerland-Uzbekistan BIT.120 The tribunal concluded that the term “investments” under the BIT had an intrinsic meaning (that should be considered both in ICSID and UNCITRAL arbitral proceedings) and consisted of a “contribution that extends over a certain period of time and that involves some risk”.121 Finally, the tribunal in Abaclat v. Argentina,122 case in which the disputed assets were state bonds issued by Argentina in order to restructure its sovereign debt,123 refused to apply the Salini test.124 Instead, the tribunal based its analysis on its own definition of investment, which consisted of two aspects: (1) a contribution and (2) the rights and value that derive from that contribution.125 In a very original reasoning, the tribunal considered that, while the ICSID Convention’s definition of “investment” focused on the first aspect, the BIT’s definition focused on the second aspect.126 However, the tribunal added that, even if it had approached the definition of the term “investment” without looking for a meaning of “investment” under the ICSID Convention, but rather only. 119. Ibid., ¶¶ 196 – 204.. 120. Ibid., ¶ 206.. 121. Ibid., ¶ 207.. 122 Abaclat and Others v. Argentine Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/07/5 (formerly Giovanna a Beccara and Others v. The Argentine Republic), Decision on Jurisdiction and Admissibility (August 4, 2011). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0236.pdf 123 Ibid., 124. Ibid., ¶¶ 363 and 364. Ibid., ¶ 346. 126 Ibid., ¶¶ 347 – 350. 125.

(38) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 38 looking at the definition of “investment” provided by the applicable BIT, it would have arrived to the same conclusion.127 C.. Brief Overview of Decisions Rendered During 2018 and 2019. After a thorough examination of the decisions rendered by ICSID tribunals and ad hoc committees during 2018 and 2019 (and already published) in disputes where the ICSID Convention was applicable, certain interesting remarks can be made regarding the approach described and analyzed in this section. Out of 28 decisions, only 5 sought an additional definition of the notion of “investment” (to the one provided by the applicable IIA). While the tribunal in Masdar Solar v. Spain128sought an inherent definition of the term “investment”, the committee in Quiborax v. Bolivia129 relied on an adjusted version of the Salini criteria, as well as the tribunal in Casinos Austria v. Argentina.130 As mentioned in section I (A) (3), the tribunal in Unión Fenosa Gas, S.A. v. Egypt131 applied a different set of objective criteria (although asserting that a single test comprised both the requirements of the applicable BIT and the Salini test). Finally, unlike. 127. Ibid., ¶ 369. Masdar Solar & Wind Cooperatief U.A. v. Kingdom of Spain, ICSID Case No. ARB/14/1, Award (May 16, 2018), ¶¶ 193 – 202. Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw9710.pdf 128. 129. Quiborax S.A. and Non-Metallic Minerals S.A. v. Plurinational State of Bolivia, ICSID Case No. ARB/06/2, Decision on Annulment (May 18, 2018), ¶¶ 146 – 153. Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw9677.pdf 130. Casinos Austria International GmbH and Casinos Austria Aktiengesellschaft v. Argentine Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/14/32, Award (June 29, 2018), ¶¶ 191 – 193. Available at: http://icsidfiles.worldbank.org/icsid/ICSIDBLOBS/OnlineAwards/C4025/DS11651_En.pdf 131. Unión Fenosa Gas, S.A. v. Arab Republic of Egypt, ICSID Case No. ARB/14/4, Award (August 31, 2018), ¶¶ 6.4, 6.67 and 6.76). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10061.pdf.

(39) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 39 these decisions, the tribunal in Cortec v. Kenya132 was the only tribunal during 2018 and 2019 that applied the Salini criteria as jurisdictional requirements without modifying any of them.. 132. Cortec Mining Kenya Limited, Cortec (Pty) Limited and Stirling Capital Limited v. Republic of Kenya, ICSID Case No. ARB/15/29, Award (October 22, 2018). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10051.pdf.

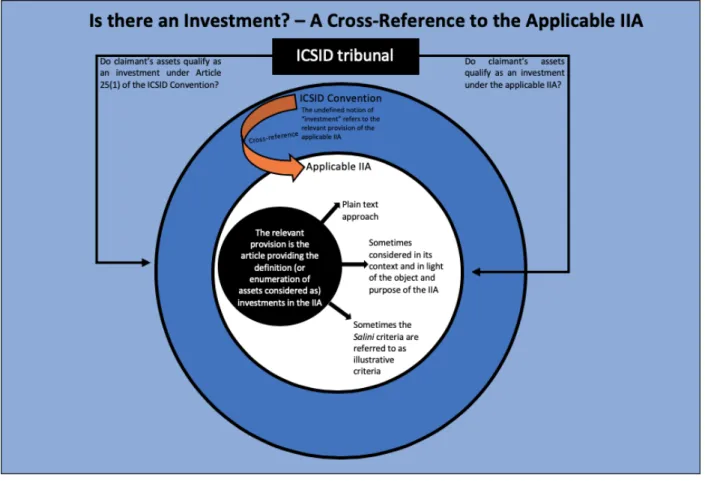

(40) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 40 II.. A Cross-Reference to the Applicable IIA Refusing to refer to the Salini criteria as jurisdictional requirements, and further. considering that the term “investment” does not have a meaning of its own (independent of any definition provided in an IIA or attributable to the ICSID Convention), some ICSID tribunals have interpreted the lack of a definition of the term “investment” in Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention as a cross-reference to the definition of (and/or enumeration of transactions, operations and assets considered as) “investments” provided by the applicable IIA. While some of these tribunals have exclusively relied on this definition (sub-section A), some others have taken into account the object and purpose of IIAs as well (sub-section B). Some tribunals have mentioned the Salini criteria, but only as illustrative and non-binding criteria (sub-section C). The decisions rendered during 2018 and 2019 show a clear trend regarding how many tribunals have taken one of these approaches until the time for writing (sub-section D). As it will be shown below, these three groups of tribunals have ultimately determined whether an investment exists or not relying mainly on the applicable IIA and, more importantly, without searching an additional definition of the notion of “investment” (unlike the tribunals mentioned in section I). A graphic representation of this approach is found in figure 2 below..

(41) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 41. Figure 2. Graphic representation of cross-reference by ICSID tribunals to the definition of “investment” provided in the applicable IIA..

(42) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 42 A.. Plain Text Approach. As mentioned above, the first distinguishable methodology among investment treaty tribunals which have not sought an applicable definition to the undefined term “investment” in Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention (either relying on the Salini criteria, a modified version, another set of objective criteria or on an abstract and independent definition of the term “investment”) consists of simply referring to the definition and/or enumeration provided by the relevant provision of the applicable IIA. One of the hallmark cases in which an ICSID tribunal took this approach is Fedax v. Venezuela133 due to the fact that it was the first ICSID case in which an objection to jurisdiction related to the requirements of the ICSID Convention that an underlying transaction must meet was raised.134 In this case, the claims were related to six promissory notes issued by Venezuela and endorsed in favor of the claimant. 135 The tribunal stated that the main issue regarding its jurisdiction over the dispute was whether an investment within the meaning of Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention was involved.136 Acknowledging the intentional lack of a definition of this term in the ICSID Convention, the first step of the tribunal’s analysis was to analyze how to interpret this term.137 Relying on the opinion of distinguished commentators, this tribunal considered that term “investment" should be interpreted broadly.138 Furthermore, the tribunal considered that loan. 133. Fedax N.V. v. The Republic of Venezuela, ICSID Case No. ARB/96/3, Decision of the Tribunal on Objections to Jurisdiction (July 11, 1997). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/casedocuments/ita0315_0.pdf 134 Ibid., ¶ 25. 135. Ibid., ¶¶ 16 and 18.. 136. Ibid., ¶ 18.. 137. Ibid., ¶ 21.. 138. Ibid., ¶¶ 20 – 23..

(43) THE DEFINITION OF “INVESTMENT” IN THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN IIAs AND THE ICSID CONVENTION 43 contracts qualified as investments under the ICSID Convention, referring to decisions rendered previously by other ICSID tribunals.139 Therefore, this tribunal considered that the enumeration of operations considered as investments provided by the Netherlands-Venezuela BIT was sufficient to hold that it had subject-matter jurisdiction over the dispute.140 A couple of years later, the tribunal in Mihaly v. Sri Lanka141 had to determine whether expenditures made during negotiations with the government of Sri Lanka for the construction of a power generation facility that never resulted in the conclusion of a contract qualified as an investment or not.142 The tribunal deemed that Sri Lanka was absolutely clear in its refusal to enter into any obligations before the signature of a contract.143 But, most importantly, the tribunal did not mention the Salini criteria or any abstract definition of “investment” in order to address the lack of a definition of this term in the ICSID Convention. Instead, besides the absence of contractual obligations in favor of the claimant, this tribunal relied exclusively on the provisions of the Sri Lanka-United States BIT to hold that the expenditures in question could not qualify as an investment.144 In Mitchell v. Congo,145 the claimant argued that the assets that had been used to establish a law firm in the Democratic Republic of the Congo qualified as an investment under the applicable. 139. Ibid., ¶ 26.. 140. Ibid., ¶¶ 31 and 32. Mihaly International Corporation v. Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, ICSID Case No. ARB/00/2, Award (March 15, 2002). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/casedocuments/ita0532.pdf 142 Ibid., ¶ 48. 141. 143. Ibid., ¶ 51 and 59.. 144. Ibid., ¶ 61.. 145. Mr. Patrick Mitchell v. Democratic Republic of the Congo, ICSID Case No. ARB/99/7, Excerpts of the Award (February 9, 2004). Available at: https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw1195.pdf.

Figure

Documento similar

MD simulations in this and previous work has allowed us to propose a relation between the nature of the interactions at the interface and the observed properties of nanofluids:

Government policy varies between nations and this guidance sets out the need for balanced decision-making about ways of working, and the ongoing safety considerations

Keywords: Metal mining conflicts, political ecology, politics of scale, environmental justice movement, social multi-criteria evaluation, consultations, Latin

Recent observations of the bulge display a gradient of the mean metallicity and of [Ƚ/Fe] with distance from galactic plane.. Bulge regions away from the plane are less

In the previous sections we have shown how astronomical alignments and solar hierophanies – with a common interest in the solstices − were substantiated in the

(hundreds of kHz). Resolution problems are directly related to the resulting accuracy of the computation, as it was seen in [18], so 32-bit floating point may not be appropriate

The taken approach focuses in the definition of a common component framework that allows the definition of components that can be reused in different systems, as well as in

Even though the 1920s offered new employment opportunities in industries previously closed to women, often the women who took these jobs found themselves exploited.. No matter