Local disaster risk reduction: Lessons from the andes

Texto completo

(2) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes Author: Allan Lavell Contributor: Christopher Lavell This document is the result of a process promoted by the Andean Committee for the Disaster Prevention and Relief - CAPRADE, in the framework of the implementation of the Andean Strategy for Disaster Prevention and Relief - EAPAD to identify initiatives and experiences with risk management of disasters and local sustainable development in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. This publication was made possible with the financial support of the European Union and the Andean Community, and implemented by the Andean Community Disaster Prevention Project - PREDECAN.. Technical Secretariat of the Andean Community Paseo de la República 3895, Lima 27 - Perú Phone: (511) 411 1400 Fax: (511) 211 3229 Web site: www.comunidadandina.org PREDECAN Project Director: Ana Campos García Team Leader International Technical Asistance: Harald Mossbrucker (2005- March 2009) Jan Karremans (2009) First Edition Author: Allan Lavell Contributor: Christopher Lavell Cover artwork and layout: Leonardo Bonilla Photography: PREDECAN Lima, Perú June, 2009.

(3) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. Allan Lavell Contributor: Christopher Lavell. 1.

(4) Acronyms AMEC:. The Ecuadorean Municipal Association. CAPRADE:. The Andean Committee for Disaster Prevention and Response. C-DRM:. Community Disaster Risk Management. CEPREDENAC:. The Central American Coordinating Centre for Natural Disaster Prevention. COOPROCONAS: Cooperativa de Trabajo Asociado. 2. CIPS:. Comitato Internazionale Per Lo Sviluppo dei Popoli. DPAE:. The Bogota Department for Disaster Prevention and Response. DRR:. Disaster Risk Reduction. EC-DIPECHO:. The European Community Humanitarian Office Disaster Preparedness Programme. FUNDEPCO:. Communitary Participative Development Fundation. HFA:. Hyogo Framework for Action. ISDR:. International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. LA RED:. The Latin American Network for the Social Study of Disaster Prevention. NGO:. Non Governmental Organization. PREDECAN:. The Andean Community Disaster Prevention Project. PP:. Pilot Project Initiative-PREDECAN-CAPRADE. L-DRM:. Local Disaster Risk Management. SE:. Significant Experience Initiative-PREDECAN-CAPRADE. U.N.:. United Nations. PREDES:. Centre for Disaster Prevention, Peru.

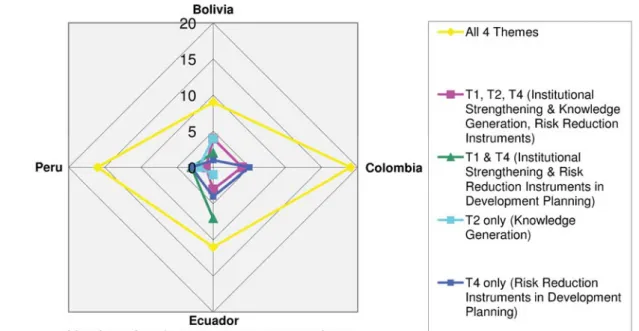

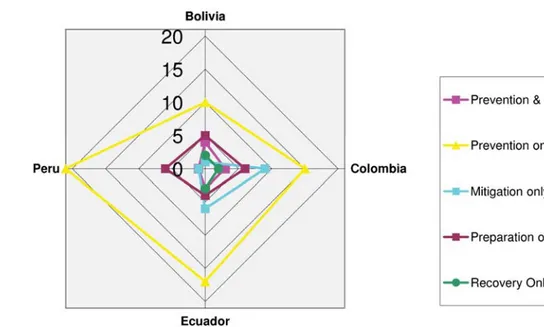

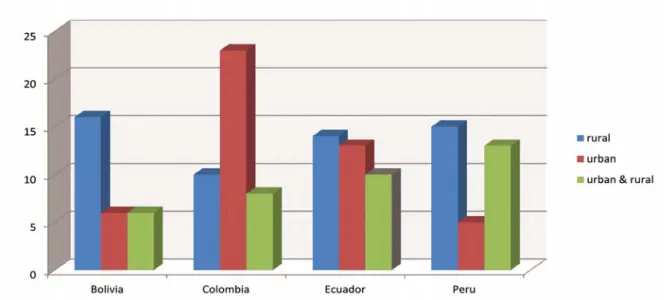

(5) Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...........................................................................................................................5 2. Selecting and Evaluating the Significant Experiences and Pilot Projects: Criteria and Concepts ....................7 2.1 Determining the Most Significant Experiences: Process and Criteria .....................................................7 2.2 The Local Risk Management Pilot Projects: Goals and Process .......................................................... 11 2.3 Clarification and Debate on Concepts and Definitions .................................................................... 11 2.3.1 Corrective, Prospective and Residual-Response Disaster Risk Management .................................. 11 2.3.2 Local and Community Disaster Risk Management: Clarifying Levels and Terms .............................. 15 2.3.3 How to define “local” ................................................................................................. 16 2.3.4 Territory and risk ....................................................................................................... 18 2.4 Significant Experiences and Pilot Projects: Complementary Approaches .............................................. 18 3. Methodology: Variables, Levels of Analysis and Parametric Concepts .................................................. 19 3.1 Territorial Delimitation of Intervention Levels ............................................................................. 21 3.2 The analytical variables and contexts ....................................................................................... 22 3.3 Appropriation and ownership ................................................................................................. 23 3.4 Process versus product ......................................................................................................... 24 4. The 139 Experiences: An Overview of Approaches and Emphases ....................................................... 25 4.1 Territorial Intervention Levels and Rural-Urban Location ................................................................ 25 Figure 1: Rural / urban project distribution............................................................................. 27 4.2 Promotion, Execution and Finance ........................................................................................... 28 Figure 2: Number of projects per implementing, financing entity type ............................................ 28 Figure 3: Project scale by implementing entity type .................................................................. 29 4.3 From risk to development or development to risk: the role of risk prevention and mitigation and differing development instruments or strategies .................................................. 30 Figure 4: Management approach per country............................................................................ 30 Figure 5: Top management themes per country ......................................................................... 32 Figure 6: Top management goals per country ........................................................................... 33 4.4 Management Themes and Goals .............................................................................................. 34 Figure 7: Project complexity by affected population size, country ................................................. 34 5. Analytical Considerations and Lessons Learned: Some Notions and Conclusions Derived from the Sixteen Most Significant Cases ..................................... 35 5.1 The Territorial and Scale Factor .............................................................................................. 35 Figure 8: Number of projects per maximum affected population ................................................... 36 5.2 The Risk-Development Link ................................................................................................... 38 5.2.1 Views of Development, Risk and the Development-Risk Linkage ............................................... 39 5.2.2 Strategies or Approaches to Development-Based Risk Reduction .............................................. 40 5.2.3 Levels and Types of Intervention and the Development –Risk Problematic ................................... 43 5.2.4 Sustainability ........................................................................................................... 43 5.3 Participation, Ownership and Local Resources ............................................................................. 45 5.4 Process and project ............................................................................................................ 47 5.5 External contacts and relations .............................................................................................. 49 6. Summary and Conclusions ....................................................................................................... 50 6.1 General Considerations ........................................................................................................ 50 6.2 Principle Conclusions ........................................................................................................... 51 Bibliography ............................................................................................................................. 53 Annexes .................................................................................................................................. 55 Annex 1 ................................................................................................................................... 56 Aneex 2 ................................................................................................................................... 74. 3.

(6)

(7) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. 1. Introduction From November 2007 to November 2008, the Intergovernmental Andean Disaster Prevention and Relief Committee (CAPRADE) promoted a sub-regional project on “Practice and Policy for Local Development when Faced with Disaster Risk: Identifying Significant Experiences” (the SE initiative). It received funding and technical support from PREDECAN, the Andean Community Disaster Prevention Project, itself financed by the European Commission and the member countries of the Andean Community, between 2003 and 2009. From early 2007 to late 2008, CAPRADE also promoted and funded a pilot project for a comprehensive local level risk management initiative in one municipality in each of the four member countries of the Andean Community - Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. The SE initiative aimed to identify and systematize information about risk reduction and control intervention at the “local” levels, promoted by a wide variety of organizations, institutions or individuals. This would help us to understand and communicate better the different conceptual, methodological, instrumental and practical lessons learned in the Andean Sub-region from disaster risk reduction practice. The concept of “significant” was used instead of “best” or “good” practice in order to promote projects that may or may not have turned out “successfully” but which would provide important information about risk reduction management and its requirements, complications, successes and failings. The Pilot Project’s objective was to strengthen capacities for local comprehensive risk management. It would use methodological and conceptual tools and ideas developed at the national level through other PREDECAN project themes, linking global risk reduction initiatives. to local development, land use and public investment planning. The documentation produced by these two projects includes: •. An information database on the 229 cases originally presented for consideration from the four countries;. •. executive summaries for 166 of the original 229 cases from the four countries;. •. a catalogue of Significant Experiences, (the SE Project) including three to four page resumes of the 12 most significant experiences per country;. •. a formal and independent analytical systematization of the four most significant experiences per country;. •. an internal project systematization of the results of the four local level risk management Pilot Projects.. This paper analyses the information and evidence provided in these documents and the project systematizations. Our purpose is to provide an Andean sub-regional analysis with conclusions and evidence that help us understand the progress made with the conceptual and theoretical bases and the implementation of what are known as Local Disaster Risk Management (L-DRM) and Community Disaster Risk Management (C-DRM). The themes of L-DRM and C-DRM have come to the fore in the debate and practice of disaster risk management over the last twenty years, and particularly during the last ten. Relating and linking specific disaster risk reduction aims to improvement in local development opportunities, increased livelihood opportunities and poverty reduction has become increasingly important. The debate over concepts and practice, typologies and approaches, definitions and disagreements has increased to the same extent (see, amongst others Maskrey, 1988;. 5.

(8) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. Wilches-Chaux, 1998; Zilberth, 1998; Lavell, 2004; Abarquez and Murshed 2004; Venton and Hansford, 2006; Cannon, 2007; Global Network of NGOs for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2007; Global Network of NGOs for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2008; Lavell, 2009).. of “local level”, specify its different uses, and consider the main parameters or axes used for comparative analysis. •. Section four briefly describes and explains the varying ways the risk reduction problematic is formulated, implemented and addressed through the projects in the four countries. This covers the questions: who does the promoting; what is promoted; what are the territorial levels at which the projects are usually promoted; what risk reduction approaches are most used; what themes are dealt with and what management objectives are most often pursued; and who funds and monitors the projects. This analysis is based on the 139 cases which complied with PREDECAN project requirements (out of the original 229 applicants and the 166 that presented executive summaries). We compare characteristics of these 139 documented projects and those that were selected as the 48 semi-finalists and 16 finalists through the project evaluation procedure.. •. Section five analyses how the case studies help us to understand concepts and practice, the formulation of public policy and the prominent issues of sustainability and replicability. We use the analytical precepts established in our chapter on methodology which were themselves used throughout the PREDECAN evaluation procedures. The main subjects discussed are: developmentrisk relations, participation and ownership, external and internal relations, processversus product-based interventions and the various levels or types of “local” intervention identified.. •. The last section presents a series of conclusions and recommendations based upon the chief features of the top projects.. The approaches taken in the projects identified in the CAPRADE-PREDECAN SE initiative, and the concepts and evaluations established for selecting significant practices are largely based on the debates and conclusions in such sources. When the current project commenced, these covered or summarized a significant part of the “state of the art” on this topic. We hope this paper will add to this debate and definition, with evidence from case studies conducted in a part of the world with its own particularities, culture, history and experience, building on existing progress and precisions in local disaster risk management practice. Our analysis is structured and presented as follows:. 6. •. Section two presents details of the process used in the SE initiative and the PP project, with information on case study contentions, basic concepts, evaluation and selection criteria and systematization of results. We will address some preliminary conceptual considerations here, including the origins of the ideas used to substantiate the selection and evaluation procedure. We will focus on the ways the CAPRADE-PREDECAN projects incorporate and contribute to the concepts, methodologies and practices discussed in previous works on the topic. We will also look at the debates over and fine-tuning of concepts and definitions.. •. Section three lays out the methodological procedures and criteria to be used in our analysis and comparison of experiences and pilot projects. We will discuss the concept.

(9) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. Annexes with the English titles of the 48 most significant experiences and summaries for the top 18 projects (two pairs of projects were merged to reach the final 16) are provided (see Annexes 1 and 2). Given that some readers may have little knowledge of Spanish this information is helpful to ascertain project themes and aims. Spanish speaking readers may refer to project documentation available on the PREDECAN web site (http://www.comunidadandina.org/ predecan/concurso/index.html) in order to gather more data and facts on the top 48 cases. Because of the nature of this paper and the deadline to be met, it was not possible to attempt an exhaustive analysis. We give details of the procedure used for analysis in Section 2, but here we will clarify briefly that more emphasis has been given to the top four most significant experiences, followed by the remaining 12 finalists, the remaining 32 semi-finalists, and then the remainder of the qualifying 139 cases. Details from the four Pilot Projects will be used to substantiate conclusions and findings where pertinent. We will try to use examples from the cases as they pertain to important aspects of the problematic, its definition and practice. This document is the product of a contract between its author and PREDECAN and the ideas expressed are solely the author’s responsibility and do not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsoring agency. This paper could not have been written without the inspirational inputs of case study systematisers and the support and contributions of PREDECAN executive staff. Our most sincere thanks to all of these project members, and to all those that participated in the projects throughout the Andean Sub-region - NGOs, community groups, municipalities, government agencies, international organizations, and others.. 2. Selecting and Evaluating the Significant Experiences and Pilot Projects: Criteria and Concepts 2.1 Determining the Most Significant Experiences: Process and Criteria In late 2007, an invitation was widely extended to diverse organizations (municipal associations, government risk-management institutions, NGO networks etc), for the presentation of local level disaster risk reduction experiences in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. The invitation indicated criteria as to the type of social actor who could present an experience and as to the range of themes and areas of intervention considered relevant. These included NGOs, governmental sector and territorial agencies, municipalities or clusters of municipalities, community organizations, universities and other academic centres, international organizations, and independent professionals and consultants. The experiences had to deal with risk reduction and control in one of two main ways. Explicitly, with the project described primarily in disaster risk and management terms; or implicitly, describing main-stream development goals and using risk management tools and instruments to strengthen these and their sustainability. This difference can be clearly seen taking the example of a population group already subjected to disaster risk factors and which has probably already experienced loss and disaster, which explicitly decides to intervene, thus reducing existing risk factors, and, on the other hand, another group which, in contrast, sees the control of risk factors as essential to guaranteeing efficiency, efficacy, productivity. 7.

(10) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. 8.

(11) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. and security. The difference between going from risk to development and from development to risk has been previously elaborated by Lavell (2004). It is an essential distinction and the move from a risk to development approach to a development to risk approach can be seen to mark progress in the ways we see disaster risk reduction and the methods open to us to achieve this. The distinction is also found in the ideas of “corrective” and “prospective” risk management that we will discuss in more detail later (see Lavell, 1998 and 2004). With regard to the risk-development link, it has been suggested in PREDECAN literature and elsewhere that although many types of activity may lead to risk reduction, we should reserve the term “disaster risk management” for those actions, strategies and activities that explicitly address the theme in a corrective or prospective manner. In other words, although many development projects may in fact “unconsciously” lead to risk control and reduction, unless this is made explicit as a goal they should not be considered part of disaster risk management practice as such. This distinction is necessary to limit our field of inquiry, but it is also a “slippery slope”, since the foremost aim should always be to promote “good” development which in itself leads to a control of risk factors, whether this is made explicit or not. Besides the adherence to one or another of the two approaches described above, the experiences presented could cover any one or more of the following intervention or management themes: institutional strengthening and increases in political commitment to risk management; the introduction of risk reduction aspects into local culture; knowledge or information management; and the introduction of risk reduction in existing or future local level development practices and instruments. These types of emphasis mirror in good part the primary objectives laid out in the U.N inspired Hyogo Framework for Action and the CAPRADE Andean Strategic Plan (see, http://www.. caprade.org/caprade/index.php?option=com_ content&view=article&id=26). Finally, they could address any or all of the disaster risk management goals - prevention, mitigation, preparedness and response, or recovery. A total of 229 experiences were originally presented in the four countries (Bolivia, 63; Colombia, 63; Ecuador, 42; Peru, 61). Of these, 166 presented an executive summary of the work undertaken that would qualify them for further consideration (Bolivia, 32; Colombia, 50; Ecuador, 40; Peru, 44). Of these, 27 were eliminated for not meeting project requirements. The final tally of qualifying experiences was 139: Bolivia 28; Colombia, 41; Ecuador, 37; and Peru, 33. A national selection committee then evaluated the projects according to established criteria in order to whittle down the original number to what were considered the 12 most significant cases per country. The criteria included the presentation of a complete set of documentation, the clarity of the experience description, the relevance of the experience according to the SE initiative requirements, and the clarity and applicability of lessons learned. This first level of selection criteria was more routine than substantial, and more formal and practical than conceptual. Following this first evaluation process, the 12 country experiences were then presented at a national meeting attended by diverse interested parties from civil society, government, financing agencies and local population groups. A committee consisting of national institutions, members of CAPRADE, municipal associations and PREDECAN representatives evaluated the experiences according to eight established criteria: •. the impacts on involved actors, institutions and social groups;. •. the application of relevant approaches, strategies, methodologies and innovative practices;. 9.

(12) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. •. the links established with cross-cutting issues (gender, cross-cultural, human rights etc.);. •. sustainability;. •. options for replication, considering adaptations to different local realities;. •. the contribution to the theory of local risk management;. •. the potential to influence public policy;. •. inclusiveness of management emphases (prevention and mitigation of risk, preparedness, recovery, etc.).. This procedure led to the selection of four cases per country which then entered the final round for selecting the “most significant” case in each country during a final sub-regional workshop held in Lima in November 2008. The four most significant country cases were then given the opportunity to meet in Trento, Italy, to study and discuss risk management procedures there. Trento is part of the implementing Consortium that provides International Technical Assistance for the PREDECAN project. The criteria for evaluating and selecting the “most significant” cases included:. 10. •. how far local actors and resources were incorporated and strengthened in the project process;. •. how the relationship between risk and development was established and implemented;. •. the levels and types of articulation achieved with external actors and economic and social contexts;. •. concrete impacts on involved actors, institutions and social groups;. •. the expected levels of sustainability; and. •. the potential for replicability, considering adaptations to local conditions.. Some criteria used in the previous selection process were maintained and other significant aspects were introduced. The criteria and parameters established throughout the process, and its several different stages, in many ways reflect the existing “state of the art” and knowledge on local and global level risk management practice. The bases for ideas on participation, appropriation and ownership by local communities and up-scaling to regional and national levels arise mostly from notions originally put forward by Maskrey (1988) and Wilches Chaux (1988) and promoted and developed by The Latin American Network for the Social Study of Disaster Prevention- LA RED- in the region and elsewhere during the 1990s and 2000s. Later systematization of knowledge and experience with local-level interventions in the Central American region led to the 2004 publication of the treatise by Lavell et al on Local Risk Management: from Concept to Practice, supported by the United Nations Development Programme and the Central American Coordinating Centre for Natural Disaster Prevention (CEPREDENAC). This treatise further substantiated the idea of the relations between risk and development, ownership and participation, extra local linkages, comprehensiveness, process versus product approaches and conditions for sustainability and replicability and placed them in a single conceptual and action framework. The ideas on risk and development and the need for risk management to be intimately related to development goals and practice, intervention and management were first developed by Cuny in 1980 and subsequently developed into an interpretative framework for understanding risk by Blaikie et al, in 1994 and in a second edition in 2004 (see Wisner et al). Their model for understanding vulnerability led to greater importance being given to development-linked arguments as to causes and intervention in the problematic..

(13) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. 2.2 The Local Risk Management Pilot Projects: Goals and Process Some preliminary criteria for identifying the municipalities to be invited to participate in the PREDECAN PP project´s bidding process were agreed upon by delegates of CAPRADE and technical institutions, such as the national geological and hydro-meteorological services. The criteria for the identification of possible candidates included the population size of the cities, the existence of hazard maps and technical information that would permit an analysis of risk scenarios; the existence of preliminary local development, land use or territorial organization plans; and the manifest interest of municipal authorities in the project and support for it at the local level. The Pilot Projects would be promoted by external non-profit agencies—NGOs, universities, etc. in coordination with local government authorities. The projects were to be participatory and demonstrative, and include elements for promoting their sustainability and replication in other areas. They should promote PREDECAN project results, findings and methodological and conceptual developments by applying these at the local level. Overall, PREDECAN project results include institutional development and strategy and policy promotion; information and knowledge management; incorporation of risk aspects in territorial development; educational and cultural aspects and emergency planning. Comprehensive disaster risk management promotion was highlighted as an aim. Projects should cover mitigation (corrective), prevention (prospective) and residual risk and response based aspects (see Section 2.3 for the development of these concepts). Following the selection procedure, pilot projects were commenced in San Borja, Beni, Bolivia facilitated by OXFAM GB and a national NGO named FUNDEPCO; in Los Patios,. Colombia, by the Colombian National Red Cross, the northern Santander regional office of the Red Cross and COOPROCONAS; in Porto Viejo, Ecuador facilitated by CIPS and in Calca, Peru by Welthungerhilfe and PREDES. Apart from developing an overall local risk management plan, the Pilot Projects were also required to have a community risk management plan, formulated within the local jurisdiction covered by the project (see section 2.3 for discussion of the local and community nomenclatures). Although the project components for the local and community plans were established by PREDECAN itself and methodological and content guidelines provided, project implementers were invited to be innovative and creative in the application of methods, concepts and instruments. Guidelines were provided for developing local and community risk management plans and incorporating risk reduction considerations in local development, land use, public budgeting procedures and programming. For the PP project, “local” is used to depict the municipal level. In contrast, as we have indicated previously, in the SE initiative, experiences from municipalities, clusters of municipalities, communities and other territorial designations could be included under the umbrella term “local level” initiatives. The discussion in the following section attempts to clarify and standardise the diverse criteria used for defining “local”. 2.3 Clarification and Debate on Concepts and Definitions 2.3.1 Corrective, Prospective and ResidualResponse Disaster Risk Management References to the corrective, prospective and residual management problematic is frequently made in the SE and PP projects. The essential differences between these categories can be expressed in the following way.. 11.

(14) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. Corrective management works in the sphere of existing risk, already affecting existing populations, their livelihoods and support infrastructure. Where such risk exists, “corrective”, “compensatory” or mitigation management techniques may be used in order to reduce existing risk levels. This type of corrective intervention may be considered what is understood traditionally as “disaster reduction”. That is to say, reducing disasters meant reducing existing disaster risk. According to Lavell et al (2004), this corrective management may be promoted in a “conservative” or “progressive” manner. In conservative corrective management, intervention is limited almost exclusively to resolving the external manifestations and signs of disaster risk—communities in unsafe locations, unstable slopes due to deforestation, unsafe buildings, lack of knowledge of local environment, etc. The type of solution may include the application of structural engineering techniques, housing relocation, environmental recovery practices, early warning systems and the provision of emergency plans. However, it does not address the root causes of such risk contexts or factors. The final result is decreased disaster risk and impacts, with the corresponding benefits this brings, such as: stabilized incomes, livelihoods and living conditions and lives saved; less infrastructure damage; wage earners saved from death or disability and the need to migrate in search of employment opportunities outside of the affected area. Moreover, lower risk levels encourage investment and improvements by and in families and/or communities. All of these factors can be expected to help stabilize development opportunities and poverty levels, but will not, in most cases, contribute particularly to an effective and significant improvement in these indicators. The “progressive” mode of corrective management combines the reduction of existing visible disaster risk factors and. 12. contexts using “traditional” methods with more development-based actions (including poverty relief goals). Here, the reduction of existing external risk factors or contexts is accompanied by the promotion of livelihood improvement, development-based activities and increased opportunities for reducing disaster risk through individual or collective self-protection mechanisms. Or, it could simply be based on progressive new development opportunities. One way or another, the implications for development and poverty alleviation are proportionately greater than with the conservative mode. Unfortunately, due to the separation that still exists between risk reduction and disaster specialists and their agencies or organizations and mainstream development agencies, at the national and international level, the number of integrated progressive corrective risk reduction projects is still limited on a global level. The use of one or the other of these modes will very much reflect different thinking on the risk reduction theme as developed over time. Work which is “traditional” (but not therefore, irrelevant), typical of the 1980s or 1990s, would be more likely to follow the conservative corrective approach. More “modern” thought, post-2000, based on more complex and comprehensive views of disaster risk and its relations to “chronic” or every-day risk tend to push towards progressive corrective management. These development-based risk reduction strategies increasingly give priority to the role of growing incomes and opportunities, livelihood strengthening, environmental management and service provision, the development of social capital, participation and decentralization, micro credit and risk transfer, etc. as strategies for reducing disaster risk (see ISDR, 2009, for an excellent review of these development-based methods). Working in the context of existing disaster risk, such mechanisms get closer to the root causes.

(15) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. 13.

(16) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. of the problem than does the conservative mode. In fact, as the development-based component increases and the disaster risk aspect becomes an associated development problem, as opposed to a problem on its own account, we tend to move away from what is commonly known as disaster risk management and get closer to development promotion, planning and management. This also helps to illustrate that in the long run, the only real way of tackling the problem of risk reduction using development and poverty reduction as a stimulus and method, is by merging the themes in a single planning framework, in the search for sustainable, secure development. Existing risk is not the only risk management concern, however, but it is the prevailing one and may be the image the general public has of risk reduction in general (or disaster prevention and mitigation). There are, however, risks that are not as yet “on the ground” but that will develop in the future. The anticipation of future risk, the control of future risk factors, and the incorporation of risk control aspects in future development and project planning, increasingly go by the name of “prospective” (or anticipatory) risk management (Lavell, 1998; Lavell et al, 2004). The principle mechanisms for this type of management goal include territorial organization and land use planning, environmental management, risk control considerations in project planning cycles and investment decisions and building codes and requirements. Residual risk management has been used in the PREDECAN project to cover preparedness and response issues where disaster associated with unresolved or unanticipated risk has to be dealt with. This is a complementary category of particular use for highlighting the residual risk problem within overall risk management. From our perspective, the activities and goals sought are in fact covered by the correctiveprospective division, as these categories can be. 14. applied throughout what is known as the risk or disaster “continuum”- pre-impact, immediate pre-impact, in emergency conditions, and during rehabilitation and reconstruction. The advantage of highlighting such practice is in reminding us that improvements to disaster response will inevitably be needed whilst we do not get on top of the risk reduction and prevention problem. Prior to event impact and ensuing disaster, existing risk levels may be mitigated by retrofitting buildings and infrastructure, by introducing crop pattern changes in the search for increased resilience and resistance, by the recovery of degraded natural environments and the establishment of early warning systems, etc. At the same time, new risk may be prevented by an early introduction of adequate risk analysis and control procedures into project and programme planning processes. Once disaster occurs, risk reduction and control activities are implemented in order to guarantee that the existing situation does not deteriorate or spiral out of control due to the absence of elements that guarantee human security and livelihood support for the affected surviving populations. Thus, when guaranteeing adequate shelter, potable water, food stuffs and health conditions, one is in fact managing new or potential risk: risk that arises out of the new disaster conditions. And, when pulling down existing unsafe buildings, felling dangerous damaged trees, eliminating sources of possible infection and disease, treating ill or injured persons, one is in fact mitigating or reducing existing risk factors. The overall aim of disaster response can in fact be considered to be a matter of avoiding a second, maybe worse disaster due to inadequate response mechanisms—this was the subject of discussion and concern following the Nagris hurricane in Myanmar in 2008. Finally, when promoting recovery and reconstruction, any work on infrastructure,.

(17) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. livelihoods, social organization, economic transformation, etc. should adopt a prospective risk attitude in order to guarantee that risk is not reconstructed and society thus returned to its previous disaster risk context or status. Local and community-based risk management processes or projects have been run in both pre- and post-impact circumstances, following corrective or prospective principles and guidelines and using multiple instruments and approaches. The relations and opportunities for incorporating and achieving development and poverty alleviation goals vary according to emphasis, objectives and timing. 2.3.2 Local and Community Disaster Risk Management: Clarifying Levels and Terms The differences between “local and “community” have constituted a kind of incognito or passed-over topic in management literature and it is wise to delve a little more deeply into this distinction in order to better understand the management levels and needs to be considered. This is important because both of these concepts are widely used in the PREDECAN projects. Despite the fact that “community” and “local” are often seen to be synonymous (see Bolin, 2003, for example), from our perspective they do in fact refer to different territorial and social levels and should be dealt with in a different but complementary manner. One way or another, L-DRM is partially based on community level processes, interventions and actors whilst C-DRM requires support and input from the more comprehensive local (and regional and national) levels. Local - as opposed to strictly community approaches have possibly been more widely developed and discussed in Latin America than in Africa and Asia. Although it is dangerous to generalize, this may possibly be explained by. the more pervasive presence of government decentralization processes and local government structures in the Latin American and Caribbean region and the greater significance of community in the African and Asian social and territorial structures. In Latin America, community is frequently an area of intervention in diverse circumstances, particularly where we are dealing with indigenous populations. Community-based management broadly defined as:. has. been. “ the process of disaster risk management in which communities at risk are actively engaged in the identification, analysis, treatment, monitoring, and evaluation of disaster risks in order to reduce their vulnerabilities and enhance their capacities. This means that people are at the centre of decision making and implementation. The involvement of the most vulnerable is paramount and the support of the least vulnerable necessary. Local and national government are involved and supportive.” (Abarquez and Murshed, ADPC, 2004.) On the other hand, local disaster risk management involves communities to a considerable degree, but the spatial frame of reference is of a higher scale of resolution and the nature and number of involved and relevant social actors correspondingly greater, including municipal and district level authorities, local private sector interests and civil society community-based groups. Given the larger social and territorial scale of local municipal jurisdictions, the range of aspects - economic, infrastructural, social, political, cultural etc. - that may be taken directly into account is greater than in the more restricted and tightly-knit communities (the nature of social conflict and resolution also differs at these two levels to a similar extent). As with community projects and processes,. 15.

(18) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. higher level spatial jurisdictions and actors (regional, national) will and should collaborate in achieving goals at local levels, given that neither community nor locality are structurally, politically or functionally autonomous, nor do they control the resources necessary to achieve many objectives established locally or by the community. The fact that risk (and poverty) causes go beyond the limits of the community or local area means that dealing with it inevitably involves dealing with “external” actors. This is also one reason why we cannot expect local, and far less so, community-based projects to reduce completely or in part the factors that cause poverty and risk. Support from regional, national and even international policies and action is inevitably required. 2.3.3 How to define “local” In general, the local level tends to be associated with municipalities, districts, parishes or other similar political-administrative denominations. However, such sub-regional politicaladministrative divisions do not exclusively define what constitutes the local level. Whilst recognizing the difficulty of arriving at a single, clear-cut definition of “local” for risk-management purposes, one must also recognize that “local” has in fact been used in a somewhat undisciplined fashion to depict very different spatial or territorial areas such as large and small-scale urban areas, tributary river basins, agricultural areas, ethnic zones and inter-municipal groupings. One way or another, ‘local’ always refers to something that is larger than a community and smaller than a region or zone. However, no matter what the final spatial delimitation used, the role of local government in local management is always important and for that reason we can accept it as defining one relevant concept of the “local” level. As a mediator and arbitrator of different social interests and conflicts and as a key factor in. 16. local development, environmental, territorial and sector planning procedures, the local government’s “policy and planning” role is, in principle, of fundamental importance for risk and poverty reduction. This function is not so easily conceived or implemented at the smaller and less complex community levels. This means that when considering development and poverty relief, an inevitable question arises about the relative pertinence, efficiency and effectiveness of efforts taken at a strictly community (as opposed to a local, regional and national) levels and about the need for support and synergies between the different hierarchical levels of intervention. Moreover, if we push the argument over what really defines the local level even further, we inevitably need to ask about the potential relevance of other definitions of “local” that are not considered under the dominant administrative-political one. Clearly these are all very different and their relevance, effectiveness and efficiency as “areas” for DRR, development incentives and poverty reduction intervention may be very different too. The problem of defining ‘local’ conclusively goes beyond our options here. So, while accepting that the definition problem exists and must be considered more closely in the future, if we are to define our methodology and analytical perspective we must take a pragmatic and flexible position. For our purposes then, ‘local’ may refer to a sum of differing types or levels of spatial or territorial jurisdiction, all sub-national and sub-regional, but defined from varied perspectives – political and administrative, ecological and physical, functional, etc. While adopting this flexible position we must also accept that analysis must clearly distinguish between the principal definitions of the ‘local’ level if the analytical variables are to be usefully compared across case studies and intervention types (see next Methodology section)..

(19) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. 17.

(20) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. 2.3.4 Territory and risk The PREDECAN project guidelines clearly indicate and address the point that while risk is localized and most evident at the micro spatial levels, the causes and actors may go beyond the territorial areas where that risk is expressed. This means that actions to reduce risk must take into account and work with those contexts and actors outside of the local and community levels which contribute to the existence and persistence of localized risk. The subject of using objective “risk territories” instead of administrative and political divisions for building a risk management option was introduced by Lavell et al in their 2004 discussion. This built on previous discussions of what were called “causal” and “impact” territories. The distinction here is between the areas where actors and processes construct risk and the areas where this risk is in fact manifested. These do not always coincide and this fact leads to the parameter that risk management must be able to scale up to larger territories and its actors in order to resolve problems at a lower scale—the local and community levels, in our case. 2.4 Significant Experiences and Pilot Projects: Complementary Approaches This paper takes the SE initiative and Pilot Projects as its working material and will attempt to draw general conclusions and learn lessons regarding local level risk management, concepts and practice based on the systematized experiences. However, it should be realised from the beginning that these two projects tackle the problem from very different angles and entrance points. In the case of the SE initiative we are faced with a series of projects promoted by a wide range of different institutions and organizations under very different social, territorial, cultural. 18. and economic conditions where risk reduction may be explicitly or implicitly present as a central or peripheral objective. Here, different project promoters have constructed a view of and intervened in the problem using differing conceptual and theoretical frameworks, visions of development and risk, methodologies and instruments. Despite this diversity, the 139 experiences have all been implemented on the basis of the project teams’ particular reading of existing concepts and practice, experience and lessons learned, as these appear in the literature or existing systematizations. In some cases current concepts, knowledge and practice have been “pushed” a step further, re-drafted, criticised and modified, thereby advancing our understanding and knowledge. The analysis in this paper aims to identify those aspects that confirm, reject, re-define or push our concepts and practice forward. In the case of the Pilot Projects, implementers were asked to follow a set methodology and considerations regarding local development instruments, searching at the same time for innovation and imaginative solutions. Basically, the project incorporated the results of processes and experiences related to institutionalization, knowledge management, education, culture and development practices at the local level, promoted by CAPRADE - PREDECAN. These projects were far less flexible and mixed than is the case with the SE initiative. Thus, for the analysis we present here, the pilot project experiences serve to examine the relevance and difficulties associated with current concepts and practices. This also allows us to make progress in rejecting, accepting, amending or innovating methods at the local level. In sum, the SE initiative provides us with a look at diversity, its origins and relevance, while the Pilot Project shows us how methodological and conceptual diversity is worked out in different practical applications. The two methods are thus complementary, and drive from theory to practice..

(21) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. 3. Methodology: Variables, Levels of Analysis and Parametric Concepts The methodology designed for analysing project results and case studies considers the time limits established for our analysis (28 working days) and the particular goals sought. There are two central objectives of our methodology: i) to advance our understanding of the varied ways in which the problem of local level risk is addressed with interventions in the form of projects and processes and ii) to contribute to the conceptual precision and practical usefulness and efficacy of local level interventions in the disaster risk problematic, through promoting concepts such as sustainable development and livelihood security. These goals will be sought in our following two sections through an analysis of the processes, lessons learned, opportunities and limitations found in the application of the significant experiences and pilot projects.. extract all significant information in a single repeated and accumulative manner. Before presenting the more intensive and exhaustive analysis of the 16 most significant cases and the 4 pilot projects in our last substantive section, we will provide an analysis of more global contextual aspects based on an analysis of all 139 cases. Here we will analyze various parameters that typify the ways in which projects are conceived and promoted by diverse institutions and organizations in the four countries: types of promoting agency; emphasis on rural or urban contexts; explicit risk and developmentrisk equations; preferred management themes, from institutional strengthening to incorporation of risk aspects in development planning instruments; and funding mechanisms (a Spanish language dataset was constructed using EXCEL to record and analyze many of these variables from the original 229 project records. The dataset is located on the first tab, and summary tables by parameter, theme and country are provided in tabs 2 to 5. This spreadsheet can be downloaded from: www.comunidadandina.org/predecan/ and www.caprade.org. In all, as we have established earlier, 139 projects entered the SE arena to begin with and these were progressively whittled down to 48, then 16 and finally, the four “most significant” cases.. Here we should make an important methodological observation about the Significant Experiences project and lessons learned, before continuing with further development of the methodological aspects.. Working from a hypothesis of more to less information and greater to lesser inclusiveness and completeness as the cases proceed from the “winning” 4 to the total 139, we intend to concentrate in increasingly lower intensities on these strata, moving from the 4 to the 16 to the 32 to the 139. We will complement a more intensive consideration of the four most significant cases and the other 12 finalists with evidence from the remaining 32 semi finalists and 139 original cases, where any novel elements can be found. In this way, through a series of successive approximations we hope to. The 139 cases that formally entered the evaluation were projects put forward for consideration by their implementers because they complied with the terms of reference used for the “competition”. This was in fact confirmed by the organizers in accepting the project resumes and submitting them to further evaluation. However, when we reach the last 48, 16 and 4 cases, the criteria used to select these were objectively established by PREDECAN and went beyond the original criteria used to accept cases. These have generally provided us with images of “optimal” or best. 19.

(22) 20.

(23) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. practice local disaster risk management, as conceived by the project organizers. This process automatically excluded many of the projects originally submitted due to aspects such as their concentration on response and preparedness instead of prevention and mitigation; the limited range of management themes they dealt with; their lack of clearly established relationships between the risk and development problems; the lack of clear participatory processes; and the fact that they were product- and not process-orientation. Thus, although these projects clearly contribute to risk reduction or control they were deemed to be less significant illustrations of local, development oriented, participatory risk management, promoted as a process. This of course means that in the “left behind” cases there is most possibly a wealth of information and experience with different, albeit narrower strategies, methods and instruments for risk reduction than could fruitfully be used in this analysis should time have permitted. It would be valuable for these to be more thoroughly systematized in the future. 3.1 Territorial delimitation of intervention levels As we have already pointed out, although the two projects promoted by PREDECAN relate and refer to “local” interventions, the very notion of “local” varies and is in many ways unspecified. In the pilot project, it is the municipal level that carries out the intervention, thus an administrative and political definition of “local” is assumed, with a separate category identified in terms of “community” level interventions. This simple, direct and unilateral approach is not seen in the SE project. In this latter situation a review of the 48 most significant cases reveals a varied selection of territorial areas for intervention, as well as complexity of the units intervened. Thus, while. a mega city like Bogota and medium and smaller cities or towns such as Manizales and Babahoyo are included, so too are groupings of small, rural, highland communities in Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia. At another level of resolution, river basins and ecological zones are the basis for intervention. While this varied use of the simple term “local” provides richness to analysis it could also be confusing, since for the purposes of comparative analysis we are (or would be) mixing different spatial and social categories and levels, which would make unilateral conclusions impossible unless we distinguished internally the exact level of intervention. Hence, whilst our analysis attempts to arrive at more general conclusions, we also accept that we need specific analysis of the different spatial and social contexts. Semantically, we tend to define concepts in terms of their opposites. In this case, “local” is that which is the opposite, or distinct from, “global”. In the case of the PREDECAN projects, “global” is the national level and thus “local” is found at the other end of the territorial spectrum - typically somewhere below the subregional level. Should we decide for example that “global” referred to a city or river basin, obviously the notion of “local” would vary accordingly. Given the range of uses employed with regard to the definition of “local” we have decided to adopt a diverse spatial or territorial categorization that allows us to classify the majority of the different case studies. This includes: •. large and intermediate size cities;. •. small cities and towns;. •. community or community groupings;. •. municipalities, municipal groupings and other such expressions of local government;. •. ecological-physical areas, water basins, rural areas, that may cross municipal, district or even department borders.. 21.

(24) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. Although not exhaustive, this classification of “local” does seem to account for a good number of the experiences presented and evaluated. We are assuming that the analytical variables used to compare and study lessons and experiences vary in their expression according to these different types of “local” experience. In our next sub-section we will describe the specific analytical variables to be considered. Finally, it is important to reiterate that although we may use a variety of meanings for “local”, there is, in the end, a clear distinction between ‘local’ and ‘community’, and thus between local disaster risk management (L-DRM) and community disaster risk management (C-DRM), as we have established previously. 3.2 The analytical variables and context The process of evaluating and selecting significant experiences and the methodological input provided for the pilot projects incorporated a number of important variables, concepts and action guides. As we have seen, these were taken from ideas and concepts developed in PREDECAN’s own conceptual framework, based on previous writings and concepts developed over the last 20 years. The origins of these ideas have been briefly discussed in this paper. These same variables, concepts and notions will be taken as potential variables in this analysis. These will be considered globally and also, to the extent this is possible, in the light of the distinctions between the different expressions of “local” that we have described and outlined above. Our hypothesis is that a particular variable or parameter of good or significant practice will be expressed in different ways depending on the territorial and social level considered. If it is generally established for example that disaster risk management cannot ignore the relations with development and poverty variables and must establish a strategic and instrumental relationship for meeting. 22. development challenges, the ways in which this is expressed and worked through will inevitably vary between interventions in a large city and interventions in a small group of communities. Similarly, this is true with such variables as the incorporation of local actors and resources, the use of process-led interventions, etc. The basic parameters we will choose to govern our analysis are: the relationship between risk and development; the use of and potential created with the incorporation of local resources and actors and the ways in which ownership is achieved; the types and levels of relationship with external territories and actors; the level of comprehensiveness achieved in the approaches taken; and the role of process as opposed to project-product approaches. We will also look at the amount of consideration given to corrective, prospective and residual risk management approaches. The data used to support our conclusions was derived from a review of the resumes, systematizations and data analysis prepared by project promoters and PREDECAN personnel. Since a variety of people prepared these documents and requirements for information were not standardised, it was sometimes difficult to specify the variables chosen for our analysis in a standard and fully confidential manner. For this reason although our statements and conclusions are generally acceptable, putting exact numbers to the data is not always wise or really possible. Therefore, our analysis is more indicative and generic than specific and statistically wholly verifiable. We hope this exercise will lead to a more quantitative analysis in the future. Project promoters should study and review the information in the spreadsheet document housing the dataset and analysis to complement and extend it. The categories used in this spread sheet and the types of analysis it permits could be improved on where necessary and then.

(25) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. used as a common base for the registering of information on new projects as these are developed in the region or elsewhere. In this way a data base of immeasurable importance could be set up allowing future continued analysis and research on the topic of local risk management. We need to further develop two of the concepts that relate to the identified analytical variables before presenting our detailed analysis: ownership and appropriation and process versus product aspects. 3.3 Appropriation and ownership When using the terms “local or community based” we mean processes and projects that are basically inspired, controlled, owned, and sustained by local and/or community actors and organizations (with or without external support). That is to say, they are “grass roots” based. On the other hand, the idea of “risk management at the community and local level” is used to refer to strategies, projects and instruments used at the community and local levels, but which are essentially promoted and controlled by external actors, although the local community may participate in one way or another. In a previous publication, the author has used the notion of “community and local level risk management” to depict the grass roots approach; and “risk management at the local and community levels” to depict externally promoted and supported initiatives, thus attributing the “level” notion with a double standard (see Lavell, et al, 2004, for an exploration of these differences). Here, although we essentially accept that the use of the territorial “level” nomenclature is neutral as regards method, for convenience we suggest it be used to depict externally promoted and sustained projects while using the completely neutral ideas of Community or Local Disaster Risk Management, where the use of the terms. “based” and “level” is avoided. Thus, when referring to Community or Local Disaster Risk Management (C-DRM, L-DRM), we are making no distinction between locally or externally appropriated and owned projects or processes. Likewise, if we use the terms “local level” or “locally based” disaster risk management, it is an explicit reference either to the external promotion or grassroots bases of the project or process. Although community and locally-enacted processes always require the collaboration of external actors, the relevant local and community actors should optimally “own” the project, and the external actors should play a subordinate role. Genuine local or community participation and ownership are seen to be greater guarantees of sustainability and appropriation of the process than externallycontrolled processes. Two decades ago, Maskrey (1988) established that politically-articulated demands from the community and local levels were more likely to have impacts at the regional or national levels where highly participative and locally appropriated projects were present. He also established the efficacy of the local-based approach, since local needs and perceptions were more likely to be taken into account in process and project objectives. Similarly, autonomous commitments of local funds and resources provide a greater guarantee of sustainability than externally-managed projects. While “local or community based disaster risk management”, seen as a process, can and does exist in areas with a wide range of risk and development levels, “disaster risk management projects at the community or local level”, promoted and sustained by external actors are more likely to be predominantly located in what are termed “high or highest vulnerability” areas. These are areas where high levels of poverty exist almost without exception, poverty being a major contributing factor in disaster vulnerability. There is thus an implicit understanding that a. 23.

(26) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. community or locality, when seen from an external perspective, may be considered “equivalent” to poverty and that a primary objective of intervention is therefore, automatically, poverty alleviation (Lavell, 2009). 3.4 Process versus product Both C-DRM and L-DRM should refer to a process by means of which policy, strategy, mechanisms and instruments for disaster risk reduction and control are established and maintained rather than referring to single or multiple individual intervention products. The notion of process thus serves to highlight the fact that L-DRM and C-DRM cannot legitimately be used to refer to a single project or programme or even a series of individual projects and programmes, but rather to the superstructure within which projects and programmes are formulated and implemented, including the strategic and policy framework, knowledge management, and evaluation procedures that guide them. Thus, the projects and programmes, initiatives and actions normally analysed in order to gain insights into relations, goals, and methods are, in fact, products of the risk management process, but do not define the process as such. When risk management (analysed as a specific, independent concern or one linked to development planning) is viewed as a process, it requires permanent organizational and institutional structures that go beyond the organizations that implement particular projects. However, it must be recognised that in many instances such a permanent structure does not exist and risk management experience is mostly characterized by a series of individual, non-coordinated, non-continuous projects and programmes. Clearly this severely reduces the ability to relate to and influence development or poverty related factors, through risk or disaster reduction, as sustainability in general drops as one-off investments often turn into failed or forgotten projects.. 24. In the search for the relationship between Local and Community enacted DRM and development promotion and poverty reduction, we have to ask as to the importance of projects established at the ongoing management process level, as compared to the individual project level. In the former, links and priorities are established by a permanent and legitimized organizational or institutional structure, while in the second, they are generally established by the projectpromoting organization. It is quite possible that development and poverty reduction goals and mechanisms would be far more feasible and consistent if the process were locally or community controlled, with individual projects being promoted by local or external actors but thought out and modelled in a way that dovetails with local norms and capabilities to create a longer lasting, more sustainable process..

(27) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. 4. The 139 Experiences: An Overview of Approaches and Emphases Although the topic of disaster risk management is relatively well discussed and diffused in the countries of the Andean sub-region and in Latin America in general, it is also clear that the state of development and particular views adopted with regard to it vary substantially, country to country. We may assume that the level of development a country has achieved in the understanding and promotion of the topic, the extent to which it has been actively involved in the development of concept and practice, the range of organizations and institutions interested in pursuing risk reduction goals, amongst others, will all have a marked effect on how and what is implemented on the ground. In this section, we will briefly examine how different defining variables play out in the four participating countries. We will pay particular attention to the territorial scale of operations, the definition of urban or rural location, how the development link is established, what themes and risk management emphases are promoted and who promotes, executes and funds the initiatives. In order to do this we will use information which distinguishes between the 139 cases originally accepted for evaluation and that for the 48 and the final 16 most significant cases. This process of differential analysis will allow the reader to distinguish between the characteristics of the 139 projects originally presented and those for the cases subsequently selected using distinct evaluation criteria. As we have stated earlier, the criteria for selection or filtering of cases reflect how PREDECAN itself construed the notion of significance in relation to local risk management practice.. 4.1 Territorial Intervention Levels and RuralUrban Location Earlier in the section on methodology we pointed out the ways in which the notion of ‘local’ is used to refer to somewhat different territorial levels and extensions - cities and towns, communities, municipalities, and ecological-physical zones in particular. Consequently, interventions at the “local” level may in fact cover and benefit very different population sizes and land areas. To understand this classification we must recognise that when talking of community level we are referring to a sub-municipal level, that is spatially contiguous and that is not established or determined by political administrative boundaries. Municipal projects refer to those where the intervention level is a municipality as such even though the topic dealt with may be relatively very well defined (early warning system, land use plan, insurance scheme for poor population, etc). The regional level is used to delimit projects promoted at intermediate political administrative levels such as departments and provinces, although application of the projects may be at lower levels such as municipalities, physical areas etc. And, physical-ecological areas refer to those defined in terms of natural regions or areas such as river basins, sub river basins, ecological zones, etc. Whereas nearly 60% of all Bolivian experiences and 40% of Peruvian projects were directed at community levels, this was true in only 25% of Ecuadorean and a minimal number of Colombian projects. This pattern is even more marked in the top 12 and 4 most significant cases for each of the countries. In Bolivia, 85% of the top 12 and all of the top 4 were community-based. Most of the few projects that were not community-based were operated by the municipality. In Peru however, community level projects were poorly. 25.

(28) 26.

(29) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. represented in the last 12 and 4 cases, where the prevailing trend was in favour of municipal or regional level projects. In Colombia, municipal level projects are the majority by far accounting for 11 of the last 12 and 3 of the last 4 selected projects. After the municipal level projects, which were themselves dominated by projects from Bogota, promoted by the Prevention and Emergency organizationDPAE-, regional level projects take second place, incorporating a sum of municipalities and other lower jurisdictional levels. Ecuador also shows a clear municipal bias, with 45% of all considered cases and half of the last 12 and 4 projects falling into this category. It is interesting to see the number of the 139 total projects operated in different physicalecological areas, such as river basins, ecological zones and urban slopes in Peru (6 cases of 33) and Ecuador (6 cases out of 37) and the absence of this type of project in Bolivia and Colombia. In Ecuador, 3 of the last 12 cases and one of the last 4 are of this sort. Colombia has mainly urban based projects— small, medium and large cities- with only 12 of the considered 41 cases covering predominantly. rural areas. Ecuador shows a more balanced trend with almost equal numbers of rural and urban based projects and an important number that cover both. Bolivia and Peru had a clear preference for rural and rural-small urban centre based projects. We can only speculate on the reasons for the varying emphases because it is impossible within the framework of the present paper to determine with a high degree of confidence the dominant underlying rationale. Rural community focuses in Bolivia and Peru, the dominance of urban based projects in Colombia and the balanced urban–rural tendency in Ecuador (within municipal frameworks), can all possibly be explained in good part by the institutional or organizational backgrounds of project promoters and financers (NGOs, foundations, local governments, international agencies etc.), the natural structure of the rural-urban division (here, the more urbanized nature of Colombia and Ecuador is clear as regards overall population structure), the levels and history of decentralization and municipal and intermediate level government structures, and the varying balance and importance of community for indigenous cultures as compared with other ethnic or racial groups. The higher. Figure 1: Rural / urban project distribution. 27.

(30) Local Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from the Andes.. number of interventions based on physical or ecological zoning in Ecuador and Peru could be explained by the importance of river basin approaches to ecological management and control in these countries. Understanding overall patterns and trends will, however, require further research and analysis. Finally, it is clear that where rural and ruralsmall town biases are seen, the size of areas and population covered is in general small. Thus, the range of problems to be faced and resolved in rural areas will require up-scaling and widescale promotion by government of intervention projects. Only through a wide-ranging policy framework and government promotion could we expect to significantly advance with risk reduction in scattered rural areas. Interventions by external actors can never hope to make much progress in resolving the problem. Replication of the significant practices revealed in this study is fundamental. 4.2 Promotion, Execution and Finance Understanding the role and relevance of the multiple organizational types in differing. national contexts is important to understanding the why, where and how of things. Projects are all kick-started, executed and/or financed by any one of several types of organization. However, the range of variations and inter-relationships between the different organizations, institutions and/or individuals limits our capabilities of analysis. As with the previous considerations, it is more realistic at this point to describe patterns and tendencies than to explain them conclusively, that is, without further, more substantial research on such matters. On the whole, we can say that the differing institutional and organizational mechanisms and preferences in promotion and finance reflect the disparate history and objective conditions in which local risk management has developed in the countries of the Andean region. The extremes are established by Colombia and Bolivia. In Colombia, projects are traditionally run by government and academic institutions with municipalities (particularly Bogota) and departments each in charge of nearly a third of all projects, whilst universities started nearly 25% of the projects. Of the four most significant. Figure 2: Number of projects per implementing, financing entity type. 28.

Figure

Documento similar

This curve shows a reduction process (a) followed by another process (b) this behavior, attributed to the reduction of the environment since according to the

8 PRDE, "Improving the Development Response in Difficult Environments: Lessons from DFID Experience." Documento de trabajo nº 4 del PRDE, Poverty Reduction in

The RT system includes the following components: the steady state detector used for model updating, the steady state process model and its associated performance model, the solver

In addition to two learning modes that are articulated in the literature (learning through incident handling practices, and post-incident reflection), the chapter

For instance, (i) in finite unified theories the universality predicts that the lightest supersymmetric particle is a charged particle, namely the superpartner of the τ -lepton,

To do that, we have introduced, for both the case of trivial and non-trivial ’t Hooft non-abelian flux, the back- ground symmetric gauge: the gauge in which the stable SU (N )

During this process, the adenine was removed from the water solution by [Uracil] 0.5 -TPB-DMTP-COF, leading to a significant reduction of this nucleobase compared to cytosine,

Since differences of market regulations in United Kingdom (UK) and recent financial crises (global financial crisis-GFC 2007-2009; Eurozone debt crisis-EDC 2010-2012)