Bioenergetics mechanism and autophagy in breast cancer stem cells

Texto completo

(2) DOCTORAL THESIS. Bioenergetics mechanism and autophagy in breast cancer stem cells. Sílvia Cufí González. 2015.

(3)

(4) DOCTORAL THESIS. Submitted to the University of Girona in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with the “International Doctorate” mention.. Bioenergetics mechanism and autophagy in breast cancer stem cells By. Sílvia Cufí González 2015. Doctoral Program: Experimental Science and Sostenibility Supervisor: Dr. Javier A. Menéndez Tutor: Dr. Rafael de LLorens.

(5)

(6) TESI DOCTORAL. Memòria presentada per optar al títol de Doctora amb menció Internacional per la Universitat de Girona. Mecanisme bioenergètic i autofàgia en les cèl·lules mare tumorals del càncer de mama. Sílvia Cufí González 2015. Programa de Doctorat: Ciències Experimentals i Sostenibilitat Dirigida per: Dr. Javier A. Menéndez Tutor: Dr. Rafael de LLorens.

(7)

(8) “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us” From Gandalf to Frodo in “The lord of the ring”. “Només tu pots decidir què fer amb el temps que se t’ha donat” Gandalf a Frodo en “El senyor dels anells”. “Sólo tú puedes decidir qué hacer con el tiempo que se te ha dado” Gandalf a Frodo en “El señor de los anillos”.

(9)

(10) Agraïments Paradoxalment en aquesta vida, l’única constant és el canvi i és per aquesta raó que durant el camí, la felicitat no es troba en el destí, sinó en el propi transcurs de cadascun dels nostres viatges. Doncs d’una manera o altra, no deixem d’emprendre i assolir (o no) noves fites. És per tot això que els agraïments intenten ser també un recorregut emocional, contextual i professional des de l’inici al final d’aquesta etapa de tesi doctoral. Molts sentiments m’envolten en aquest moment (alguns d’ells en forma de llàgrimes, altres de somriures, rialles, sacrifici, il·lusió, gratitud, obstacles, moralitat, innocència, nerviosisme, etc.) mentrestant però, intento plasmar tota la meva gratitud i estima en les meves paraules. Sou tantes les persones que heu contribuït d’una manera o altra, més o menys (tots de diferent manera) a que avui estigui escrivint això, que si alguna cosa tinc clara és que tots heu viatjat i viatgeu amb i en mi, doncs més enllà d’assolir aquesta tesi doctoral (com una nova fita), el que sí que preval sou i sereu tots vosaltres (com a part inequívoca de la meva felicitat i gratitud). Penso que la tesi doctoral no comença quan et matricules a un programa de doctorat de qualsevol universitat, sinó en el moment que decideixes voler formar part d’un grup de recerca al finalitzar la llicenciatura (sinó molt abans... Montse Bellmàs: gràcies) i aquí a la primera persona a la que haig de donar les gràcies per confiar en mi en aquell moment, la Teresa. Aquella etapa “Glorie” la recordo amb tu sempre al costat, unides, gaudint de tot l’ho nou amb un somriure i plenes d’entusiasme. Gràcies. Aleshores, d’aquell projecte coordinat amb altres centres de recerca nacionals, vaig conèixer a altres persones excepcionals i em quedo probablement curta: l’Ander Urruticoechea i l’Helena Aguilar. Ander gracias por tu apoyo incondicional, por tus verdades, por tu entereza, confianza y por tratarme siempre de tu a tu. Helena, gràcies per tant compartir, per ensenyar-me tant, per cuidar-me... per mi ets un referent en molts aspectes morals i professionals de com encara hi ha bons principis, “boja”, m’encanta seguir encara en el mateix vaixell. Gràcies per tot el que vaig aprendre també al Dr. Ramon Colomer, Daniel, Mari-Luz, Bellinda, Silvia i Carlos. Just abans de tancar amb aquella etapa vas arribar tu Adri i me’n alegra que avui siguis encara present, no canviïs. i.

(11) Des de fa 6 anys que treballo també a l’Institut Català d’Oncologia a l’Hospital Duran i Reinals de Barcelona, i és d’allà on probablement tinc més bons records professionals i on m’he sentit més “realitzada” a la feina, doncs és allà on tinc els meus estimats ratolins/es. A ells no els oblido. Només pensar en tot l’entorn de l’estabulari ja m’emociona, m’omple de felicitat doncs m’hi sento com a casa. Això és així, doncs allà tinc el que per mi és com una segona mare, la Joana. Un referent amb majúscules. No tinc paraules per tu Joana. Gràcies per absolutament TOT, fora i dins de la feina, et tinc sempre present i m’encanta el saber fer i l’esperit de lluita propi de tu. A la Rosa, per ensenyar-me tant, per la teva paciència, per la teva disposició absoluta, per tant recolzament i estima. A la Glòria, per entendre’ns des del primer dia, per tanta ajuda, per tantes converses, per tants riures... A ti Charo, por tanto cariño, por ser como la prolongación de mi madre allí, por tus ganas de superación continua, por tu entereza y por preocuparte siempre de mi. A l’Anna per les nostres infinites converses, per intentar arreglar el món plegades, per les nostres filosofies amoroses, pel teu ajut sempre incondicional. No me olvido de ti Blanca, la pulsera nos mantiene unidas de alguna manera en la distancia, un ejemplo del espíritu de trabajo y de hacer las cosas con amor y ganas, fuiste de quien primero aprendí allí y eso no se olvida nunca. Encarna, por tu paciencia y ayuda. Mari, Pablo, Bryan, Erick, Carlos y Fidelia, gracias por vuestro cariño. Juntos hacéis un gran trabajo. A en Ferran, per entendre’ns des del primeríssim dia amb una mirada i poques paraules, per la teva amistat. A la Laura Barberà, per les nostres meravelloses estones dins de la SPF-1, moments i estima inoblidable. A ti Alberto, por compartir tantos puntos de vista, por ser una fuente inagotable de conocimiento y experiencia en el estabulario, por tus consejos y tu ayuda/apoyo. A en Gonzalo, per ser un tiu “collonut” en tots els aspectes. A la Mar, Gabriela, Jordi, Griselda, Juanjo, Mercè, Clara, Mireia, Lara, Laura, Iolanda, Marc, Laia, Marta, Raul, Maria, Sara, Vanesa, Wilmar... gràcies a tots vosaltres i a la gent que em dec oblidar del LRT1 i LRT2. A en Joan, per la nostra amistat, pels nostres viatges, per les teves truites de patates, pel teu bon humor. Marga pel teu suport i pels teus bons consells. A en J.Ramon, per ser el meu dermatòleg preferit. A en Josep Maria, pel teu positivisme i bon rotllo infinit que per coses de la vida seguim tenint a Girona.. ii.

(12) A partir d’aquí, ara ja si començo amb l’etapa pròpiament de doctorat i, amb ella, l’oportunitat que em va oferir un dia poder fer aquesta tesi, el Dr. Javier Menéndez: gracias por brindarme la oportunidad, por quererme en el equipo y por tanto trabajo mostrado y disfrutado. “Gana uno, gana el equipo”. A ti Alejandro, por ser mi reto personal en el lab, desde el principio a sacarte las mejores sonrisas y momentos allí. Por tanto compartir, por tu paciencia, por tu confiar, por enseñarme, por aceptarnos tal y como somos y por tantos momentos vividos que nos hacen un poco mejor (ahora pienso en como agradecería el gran Chicho estas líneas y me río). A tu Cristina, per ser un exemple d’organització, treball, esforç i dedicació. Per tenir la llibertat de dir-nos qualsevol cosa sempre. Per entendre’ns tot i les possibles diferències de caràcter inicialment. Perquè seguim units d´alguna manera molt més temps, tot i la distància i el temps. A tots els amics i companys del laboratori a Girona. Paco per ser un lluitador entusiasta innat i la teva amistat. Gerard, per mostrar-me tanta estima i per entendre’ns d´igual manera des d´un inici. Anna, per tants moments compartits i viscuts fora i dins de la feina. Rocío, per les nostres converses i els nostres “chinorrus”. Mònica pel teu saber estar i per no haver “marxat” mai. Maria, por tu dulzura y nuestras coincidències. Òscar per ser el millor infermer. Carme, Susanna, Anna P, Ari, Jose, Isa, Marta, Gemma, Judit, Ester, Neus, Roser, Esti... Ceci per mi tu també formes part del lab, tot i que no hi treballis, però m’alegra haver-te conegut i compartir tantes ferrates i bons moments amb “els homes i els petits humanots” ☺. . A la gent de l’IDIBGI, em refereixo a la Núria, Esther, Marta, Josep, Montse, Laia, etc... moltes gràcies per ajudar de manera indirecta en la nostre feina diària, igualment a l’Albert Barberà com a bon líder i responsable de la institució. Pel meu petit i fugaç viatge per terres tarragonines amb el grup de Jorge Joven. Gracias a él, a “sus chicas” y su família por acogerme. Gracias a todos los locos/as del “Master casi sin conejos”: Helena, Nuria, Carol, Yeray, Juan, Yolanda, Ana María, Sergio, Laura, Ana, Clara, Marta, Toni, David, Asun, Angel, Cristina, Eli, María Jesus, Mercè, Montse, etc... Thanks to everybody in the Salk Institute, especially to Dr. Izpisua-Belmonte to offer me this opportunity and Dr. Tomoaki Hishida to become my best mentor there. Thanks Yuriko, Eric, Nacho, Alex, CJ, Ilir, Yun, Jun, Utah, Ken, Conchi, May, iii.

(13) Peter, April, etc. I enjoyed so much my Californian experience there with you, my American family: Sara (por tu Alegría y manera de vivir), Carlos (por ser como mi hermano mayor), Helena (por entendernos tan facil en todo), Javi (por tu empatía y amistad incondicional), Mónica (por tu salero y tu buen rollo tan acaparador), Martin (por tu integridad y entereza), Irene y Jaime (por cuidar de mi), Irene y César (por vuestra predisposición), Sandra y Carlos (por vuestro bon rollete e inocencia), Andrés y Fátima (por ser las “especias” para un buen plato peruano, portugués, colombiano o lo que se precie), Mikel (por tu personalidad definida), Marta (por tu libertad), Manu y Bego (por ser “diferentes”…). But I want to thank you Sarah to be like my sister there; I will always remember my days in USA with you and your (my) friends too (Robyn, Mike, Andy, Jennafer, Barry, Courtney, Hais, Estelle... and your family as well). Doran and Aliya thanks for your hospitality and help in “my” best Californian house/environment with Asta as well. No vull deixar de nombrar també a tothom fora de l’àmbit “laboral”. A totes les meves amistats i al meu millor entorn. Les primeres, com no podia ser d’una altra manera, Putis us estimooo! (Laia, Isis, Sílvia, Anna, Lorena i Mireia), els moments juntes són tots, tots, tots inoblidables i inigualables. Per molts anys més sumant, gaudint, experimentant i compartint. Sílvia gràcies per tant i tant, ets el meu pilar en molts sentits, i que d’això tan bonic no ens “alliberem” mai! Alberto (por no separarnos Yoi), Valdi (por tu forma de ser tan única y pura), Isaïes (pel teu sentir i la teva llibertat), David (el meu masca), Javi (“mi niño”), Marc (por nuestro mejor reencuentro), Alex (tu ratona preferida que ves subir aún las escaleras), Xavi (pels teus valors), Mercè (per les teves abraçades úniques), Pau (per la teva “superioritat”), Ricardo (pel teu recolzament), Txell (per les nostres festetes), Iván (por tu buen rollo y amor a la montaña), Marina (pels bons moments passats compartits), Carles (por tu “caña”), Santi (por tu arte y buen rollo), Aleix (per la teva Energia i consciència), Pere (per la brillantor en el disseny), a ti Pablo (por tus ánimos y porqué has sido mi “empujón decisivo” en esta etapa predoctoral)... A tu Gerard, pels bonics moments viscuts, i compartir una part molt important i inoblidable de la meva/nostres vida. A la teva família. A la Nina. A en Jordi Vilamitjana, per la teva lluita, les boniques paraules i la teva confiança. Allà on siguis (doncs has marxat abans de veure dipositada la tesi). iv.

(14) A vostè, Sra. Conxita, perquè sempre ha sigut i serà un exemple en tots els sentits per a tots. A la família Grau. A en Sergi (perquè ens ho vam prometr6). I per últim, al meu avi (sigues estando conmigo guapito, te adoro...), la meva iaia (la más “completa”), els meus tiets i tietes (Ramón, Naza, Man, Viky, Nono y Sonia), als meus cosins/es (Paula, Dani, Ramon, Anna y Pol). A la meva super “Maina”: por compartir tantas cosas y por nuestros “veranos” inolvidables siempre. Os quiero mucho a todos. Gracias por ser la mejor familia que se puede tener. A en Miki, per aquests anys tan especials, pel present, per tantes coses bones, per sumar, per compartir, per estimar, per demostrar, per intentar ser millors plegats, per tantes similituds, pels viatges, per les experiències, pels detalls, per saber escoltar, pel recolzament, per la paciència, per l’ajuda, per treure el millor de mi, per ajudar-me a trobar forces i no caure. Gràcies. 7! A la teva iaia per la seva actitud envers la vida i per fer-me sentir una pallaresa més, juntament amb en Pepito a Llarvent. Exemples de lluita. Al meu referent des de que tinc consciència en aquesta vida, el meu germà. Joan, te quiero y sabes que por siempre estaremos unidos. Por nuestras señales, por nuestro sentir y por nuestra comunicación más allá de las palabras. Eres lo más preciado que tengo: Mi luz, mi todo, “mi poyo”. Siempre estás y viajas conmigo. ¡Siempre 4! Als meus pares (mis amigos y referentes en TODOS los sentidos). Papa por tu pasión y tu fuerza, eres simplemente el mejor padre. Mama por tu ternura y tu todo, soy tu proyección. Os quiero más que nada en este mundo. Sin vosotros nada sería posible. Os llevaría conmigo al fin del mundo y en el final de mis días. Sois de lo bueno, lo mejor, y aún me quedo corta. No tengo palabras, ni páginas suficientes: OS ADORO. A tots vosaltres i disculpeu si m’he deixat algú:. Gràcies, gràcies, gràcies!. v.

(15) vi.

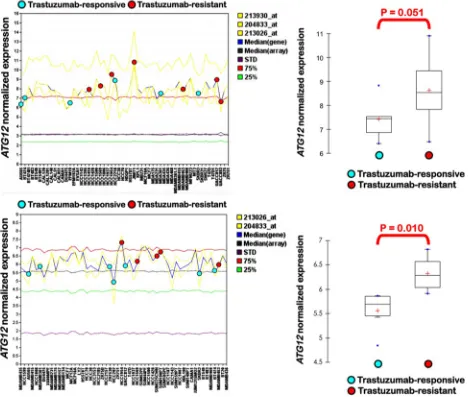

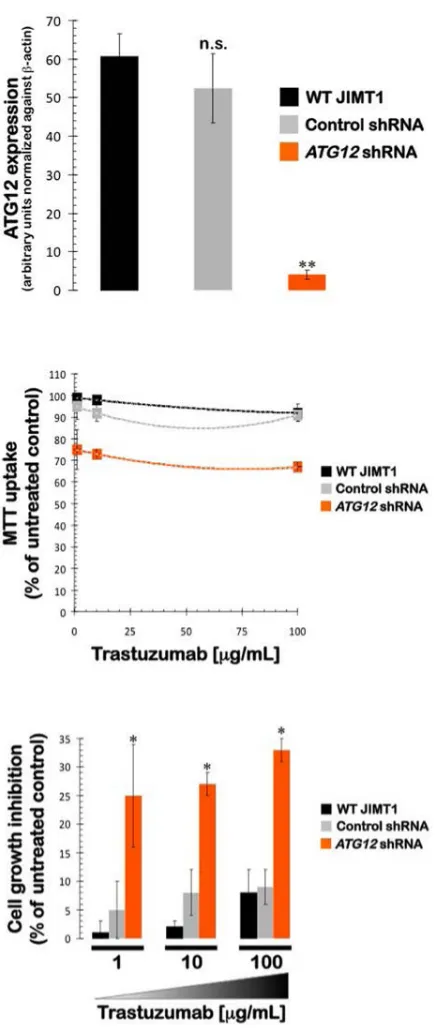

(16) List of manuscripts This doctoral thesis is presented as a compedium of four publications: MANUSCRIPT 1 Cufí S, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Martin-Castillo B, Vellon L, Menendez JA., Autophagy positively regulates the CD44(+) CD24(-/low) breast cancer stem-like phenotype. Cell Cycle, 2011 Nov 15;10(22):3871-85. IF 2011 = 5.359 Q1 CELL BIOLOGY. MANUSCRIPT 2 Vazquez-Martin A, Cufí S, Corominas-Faja B, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Vellon L, Menendez JA. Mitochondrial fusion by pharmacological manipulation impedes somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotency: new insight into the role of mitophagy in cell stemness. Aging (Albany NY). 2012 Jun; 4(6):393-401. IF 2012= 4.696 Q2 CELL BIOLOGY. MANUSCRIPT 3 Cufí S, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Corominas-Faja B, Urruticoechea A, Martin-Castillo B, Menendez JA. Autophagy-related gene 12 (ATG12) is a novel determinant of primary resistance to HER2-targeted therapies: utility of transcriptome analysis of the autophagy interactome to guide breast cancer treatment. Oncotarget, 2012 Dec; 3(12):1600-14. IF 2012= 6.636 Q1/Q1 CELL BIOLOGY AND ONCOLOGY. MANUSCRIPT 4 Cufí S, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Corominas-Faja B, Cuyàs E, LópezBonet E, Martin-Castillo B, Joven J, Menendez JA. The anti-malarial chloroquine overcomes Primary resistance and restores sensitivity to Trastuzumab in HER2positive breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2013 Aug 22;3:2469. IF 2012= 2.927 Q1 MULTIDISCILPLINARY SCIENCES.. vii.

(17) viii.

(18) Abbreviations Abbreviation. Meaning. 3-MA. 3-metiladenine. AKT. Kinase B Protein. ALDH1. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1. Ambra1. Activating Molecule in Beclin1-Regulated Autophagy. AMPK. 5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase. AP. Phosphatase alcaline. ATG. Autophagy-related gene. ATP. Adenosine Triphosphate. ATPase. Adenosine Triphosphatase. BCL-2. B-cell lymphoma 2. Bec-1. Beclin-1. BH3. Bcl-2 homology (Madan, Gogna et al.) domain. Bif1. Endophilin B1. BNIP. BCL2 and adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting proteins. BNIP3L. BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3-like. BRCA1/2. Breast Cancer Type 1/2 susceptibility protein. CAFs. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Cav-1. Caveolin-1. CD24/44. Antigene CD24/44. CD8. Antigene CD8. CDH1. Cadherin 1. CK5/6. Citokeratine 5/6. CKO. Condicional Knock-out. CMA. Chaperon-mediated autophagy. CQ. Chloroquine. CSC/s. Cancer stem cell/s. c-Myc. Myc proto-oncogene. c-Vps. Class C Vps protein complex in yeast. DAPK. Death-Associated Protein kinase. DCIS. Ductal Carcinoma In Situ. DNA. Deoxyribonucleic acid. ix.

(19) DRAM. Damage-Regulated Autophagy Modulator. Drp1. Dynamin-1-like protein. E3. Pyruvate dehydrogenase protein 3 component. ECM. Extracellular matrix. EMT. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition. ER. Estrogen receptor. ErbB2. Erithroblastic Leukemia Viral Oncogen Homolog 2. ERK. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases. FAK. Focal Adhesion Kinase. FDG. 18F-2 desoxiglucose. FIP200. An ULK Interacting protein. FIS1. Mitochondrial fission 1 protein. FOXC2. Forkhead box protein C2. FUNDC1. FUN14 domain containing 1. GABARAP. Gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor-associated protein. GATE-16. Golgi-associated ATPase enhancer of 16 kDa. GSH. Glutathione reduced. GTPasa. Guanosine Triphosphatase. HCQ. Hidroxichloroquine. HER1/2. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor ½. HIF-1. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1. HNE. 4-Hydroxinonenal. HPV16. Human papillomavirus (HPV) 16. HSC. Hematopoietic stem cells. IKK. I kappa B kinase. IL-15. Interleukine 15. INS-1. Insulin-1. iPS. induced pluripotent stem cells. iPSC/s. induced pluripotent cancer stem cell/s. JNK. c-Jun N-terminal Kinase. K-RAS. V-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog. LC3. Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3. MEF. Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast. MET. Mesenchymal-epithelial transition. x.

(20) Mfn1. Mitofusin. miRNA. Micro RNA. MMTV-PYMT. Mouse mammary tumor virus. MSC. Mesenquimal multipotential stem cells. mTOR. mammalian Target Of Rapamycin. mTORC1. mammalian Target Of Rapamycin Complex 1. NADPH. Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate-oxidase. Nix. outer mitochondrial membrane protein NIP3-like protein X. NMF2. Mitofusin 2. NO. Nitrogen monoxide. OPA1. Optic Atrophy 1. OXPHOS. Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation. P53. Protein 53, tumor supressor. P62. Protein 62, tumor supressor. PanINS. Intraepitelial neoplasy of pancreas. PAS. Phagophore Assembly Site. PE. Phosphatidyletanolamin. PI3K. Phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases. PI3P. Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. PINK1. PTEN-induced putative kinase 1. PR. Progesterone receptor. PTEN. Phosphatase and Tensin homolog. PyMT. Polyoma virus- middle T antigen Antibody. Rab7. Ras-related protein Rab-7a. RHEB. Ras homolog enriched in brain. ROS. Reactive Oxygen Species. SIO. Senescence induced by oncògenes. SNAIL. Zinc finger protein. SQSTM1. sequestosome 1. TEM. Mesenquimal-Epithelial transition. TGF- β. Transformant Growth Factor beta 1. TGN. Trans-Golgi Network. TSC2. Tuberous sclerosis protein 2 or tuberin. TWIST. basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor 1. xi.

(21) ULK. Homologous proteins in yeast-ATG. UPR. Unfolded Protein Response. UPS. Ubiquitin Proteasome System. UVRAG. Resistence gene associated with ultraviolate radiation. VDAC. Voltage-dependent anion channel. VEGF. Vascular endotelial growth factor. VSP34. Vacuolar Protein Sorting 34. Vti1p. v-SNARE yeast protein. ZEB. Zinc fi+A102:B109nger E-box-binding homeobox. xii.

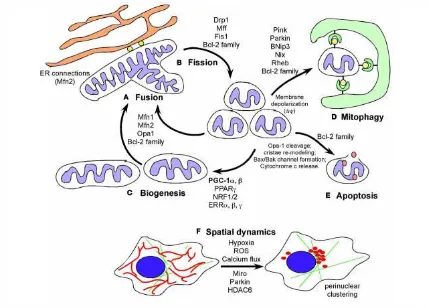

(22) List of figures. Figure 1. A) Formation of a tumor in the mammary gland. B) Organs where the breast cancer can become metastatic: brain, lung, liver, bone and in the same or the other breast. ............................................................................................................................ 23 Figure 2. Anatomy of the mammary gland. ................................................................. 23 Figure 3. Schematic representation of what happens in a cell to become a tumor. Figure from (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011). ................................................................ 27 Figure 4. Origin of breast cancer; A) In the traditional theory most tumor cells have the ability to proliferate indefinitely and generate new tumors, while B) In the theory of stem cell, only CSCs can proliferate indefinitely and generate new tumors. Figure from (Reya, Morrison et al. 2001). ................................................................................ 30 Figure 5. Tumor process stages: carcinoma in situ, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis. ..................................................................................................................... 31 Figure 6. Cellular changes during emt. loss of junctions between adjacent epithelial cells, loss of apico-basolateral polarity, degradation of the extracellular matrix and cytoskeleton modification of cells resulting in mesenchymal cells. ........................... 32 Figure 7. Involvement of the EMT and MET in the development of cancer. ............. 33 Figure 8. Warburg effect vs. anaerobic glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation. .. 37 Figure 9. Protein degradation pathways in mammals. Adapted from (MartinezVicente and Cuervo 2007). ............................................................................................ 39 Figure 10. Overview of cellular pathways in autophagy. Figure modified from (Yang, Chee et al. 2011). ............................................................................................................ 42 Figure 11. Signaling pathways that regulate autophagy. Modified from (EisenbergLerner and Kimchi 2009)............................................................................................... 44 Figure 12. Defining mitochondrial dynamics in cells. A) Mitochondrial fusion. B) Mitochondrial fission. C) Induction of biogenesis in mitochondrials. D) Process of. xiii.

(23) mitophagy. E) Apoptosis and F) Mitochondrial spatial dynamics. Figure from (Boland, Chourasia et al. 2013). ................................................................................................... 48 Figure 13. The role of autophagy in human diseases. Figure from (Mizushima, Levine et al. 2008)..................................................................................................................... 55 Figure 14. Autophagy: a new parameter in the tumor cell differentiation-state plasticity that dictates the transition rates between non-CSC and CSC cellular states Gupta, Fillmore et al. 2011).. .........................................................................................136 Figure 15. Parameters impacting autophagy-regulated metabolism reprogramming in CSCs ............................................................................................................................. 140 Figure 16. Autophagy/mitophagy and the CSC cellular state: two models. .............. 155. xiv.

(24) List of tables. Table 1. Main causes of death in developed countries (2008), data extracted from the report of the american cancer society. * number of deaths in thousands. ............... 22 Table 2. Table representing the main features of different types of breast cancer.. 24 Table 3. Differential characteristics between epithelial and mesenchymal cells. ..... 34 Table 4. Ongoing clinical trials which studied the effect of autophagic inhibitors in the cancer treatment (chen and karantza 2011). ............................................................. 160. xv.

(25)

(26)

(27)

(28) Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, Ph.D. Roger Guillemin Nobel Endowed Chair Professor Gene Expression Laboratory. May 2, 2014 To Whom it May Concern, Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, Principal Investigator and Professor in the Gene Expression Laboratory at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, San Diego, California (USA). CERTIFIES: That Sílvia Cufí González, has been in my group at the Salk Institute during the first semester of 2014, where she has performed a variety of experiments to improve her knowledge and technical experience in the field of stem cells. Sincerely,. Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, Ph.D.. 10010 N. Torrey Pines Rd. • La Jolla, CA 92037 • Phone (858) 453-4100, x1130 • Fax (858) 453-2573 E-mail: belmonte@salk.edu.

(29)

(30) La realització d’aquest treball ha estat possible gràcies al suport del Ministeri d’Economia i Competitivitat (MINECO), mitjançant la concessió d’una beca pre-doctoral del programa de formació de personal investigador (BES-2010-032066) i d’un ajut de la mateixa administració pública per realitzar una estada de 4 mesos a un cente de recerca estranger (EEBB-I-14-08350). La tesi doctoral s’ha dut a terme bàsicament entre dos centres catalans de recerca. Els experiments principalment in vitro s’han realitzat a l’Institut d’Investigació Biomèdica de Girona (IDIBGI) i els experiments amb models animals a l’estabulari de l’Institut d’Investigació Biomèdica de Bellvitge (IDIBELL) i l’Institut Català d’Oncologia (ICO) – Hospital Duran i Reinals de Barcelona. L’estada de caire internacional ha sigut al Salk Institute for Biological Studies de San Diego, California, EEUU..

(31)

(32) SUMMARY CONTENTS Summary contents AGRAÏMENTS ................................................................................................................... I LIST OF MANUSCRIPTS ................................................................................................. VII ABBREVIATIONS............................................................................................................. IX LIST OF FIGURES ..........................................................................................................XIII CERTIFICATE OF THESIS DIRECTION ......................................................................... XVII SALK INSTITUTE CERTIFICATE .....................................................................................XIX SUMMARY CONTENTS.................................................................................................... 9 SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... 13 RESUM ............................................................................................................................ 15 RESUMEN ....................................................................................................................... 17 1.. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................19 1.1.. CANCER ............................................................................................................. 21. 1.2.. BREAST CANCER ................................................................................................. 22. 1.3.. CANCER CELLS CHARACTERISTICS .......................................................................... 25. 1.4.. CANCER STEM CELLS ........................................................................................... 28. 1.5.. EPITHELIAL-MESENCHYMAL TRANSITION ................................................................. 31. 1.6.. TUMOR METABOLISM ......................................................................................... 36. 1.7.. AUTOPHAGY ...................................................................................................... 38. 1.7.1.. Cellular process of autophagy .................................................................. 39. 1.7.2. Autophagy regulation ............................................................................... 42 1.7.3. Autophagy and its detection .................................................................... 44 1.7.4. Mitophagy ................................................................................................. 46. 2.. 1.8.. THE SURVIVAL AND THE CELL DEATH IN AUTOPHAGY ................................................. 51. 1.9.. AUTOPHAGY AND CANCER ................................................................................... 52. 1.10.. PERSPECTIVES IN CANCER: TREATMENTS AND AUTOPHAGY ....................................... 55. HYPOTHESIS .......................................................................................................... 57. 9.

(33) SUMMARY CONTENTS 3.. OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................61. 4.. MATERIALS, METHODS AND RESULTS ................................................................ 65 MANUSCRIPT 1 Autophagy positively regulates the CD44+CD24-/low breast cancer stem-like phenotype .............................................................................................................. 67 MANUSCRIPT 2 Mitochondrial fusion by pharmacological manipulation impedes somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotency: New insight into the role of mitophagy in cell stemness ................................................................................................................ 85 MANUSCRIPT 3 Autophagy-related gene 12 (ATG12) is a novel determinant of primary resistance to HER2-targeted therapies: Utility of transcriptome analysis of the autophagy interactome to guide breast cancer treatment ..................................................... 97 MANUSCRIPT 4 The anti-malarial chloroquine overcomes Primary resistance and restores sensitivity to Trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer .................................. 115. 5.. DISCUSSION ......................................................................................................... 131 5.1.. AUTOPHAGY IN CANCER STEM CELLS: LESSONS FROM AUTOPHAGIC NORMAL STEM. CELLS ....................................................................................................................... 133 5.2.. AUTOPHAGY AND THE METABOLIC REPROGRAMMING IN CANCER STEM CELLS HYPOXIA-. AND STARVATION-RELATED AUTOPHAGY: A CYTOPROTECTIVE ADAPTIVE MECHANISM OF CANCER STEM CELLS AGAINST MICROENVIRONMENTAL STRESSES. ...................................................136. 5.3.. STARVATION-INDEPENDENT ACTIVATION OF AUTOPHAGY: FROM ADAPTIVE TO INTRINSIC. METABOLIC FEATURE IN CANCER STEM CELLS. .................................................................. 141 5.4.. AUTOPHAGY, SENESCENCE, AND THE GLYCOLYTIC METABOTYPE IN CANCER STEM CELLS:. FRIENDS OR ENEMIES? ................................................................................................... 142 5.5.. FRIENDS: AUTOPHAGY AS A FACILITATOR OF THE WARBURG EFFECT. ....................... 144. 5.6.. ENEMIES: AUTOPHAGY AS AN ANTAGONIST OF THE WARBURG EFFECT. .................... 148. 5.7.. MITOPHAGY: A DIRECT WAY TO CONNECT AUTOPHAGY WITH THE METABOLIC. REPROGRAMMING OF CSC..............................................................................................150. 10.

(34) SUMMARY CONTENTS 5.8.. MITOPHAGY AND THE “REVERSE WARBURG EFFECT”: CONNECTING AUTOPHAGIC. STROMA WITH CANCER STEM CELLS................................................................................. 152 5.9.. THE AUTOPHAGY-REGULATED MIGRATORY/INVASIVE PHENOTYPE IN CANCER STEM CELLS .......................................................................................................................156. 5.10.. TARGETING AUTOPHAGY IN CANCER STEM CELLS: A THERAPEUTIC COROLLARY .........158. 6.. CONCLUSIONS ..................................................................................................... 161. 7.. BIBLIOGRAPHY .....................................................................................................165. 8.. APPENDIX I. CURRÍCULUM VITAE. ...................................................................... 197. 9.. APPENDIX II. TESI EN CATALÀ. ........................................................................... 205. 11.

(35)

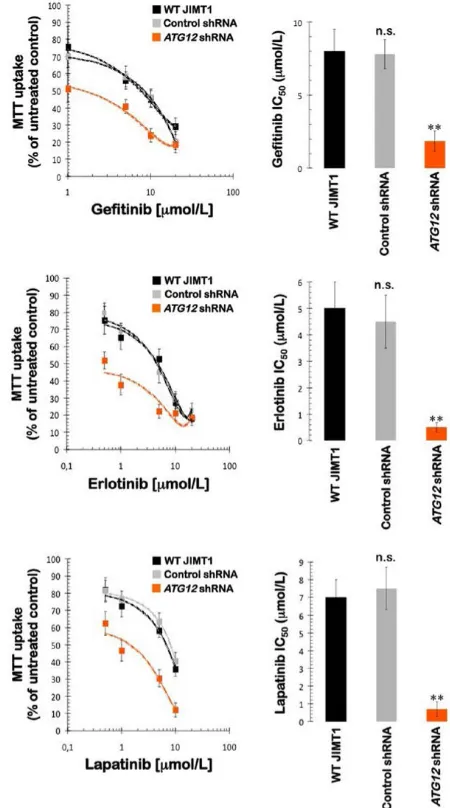

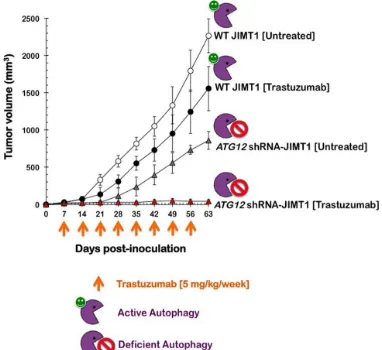

(36) SUMMARY Summary. Autophagy is a self-catabolic process that maintains intracellular homeostasis and prolongs cell survival under stress via lysosomal degradation of cytoplasmic constituents and recycling of amino acids and energy. Autophagy is intricately involved in many aspects of human health and disease, including cancer. Autophagy is a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis, acting both as a tumor suppressor and a protector of cancer cell survival and elucidation of its exact role at different stages of cancer progression and in treatment responsiveness is a complex and challenging task. Here we have showed how the reprogramming of energy metabolism and autophagy are functionally independent of other key attributes in molecular cell malignancy events and therefore required intrinsically to allow acquisition of aberrant capabilities like immortality, self-renewal and differentiation characteristics of cancer stem cells. In addition, we have analyzed the process of autophagy in the acquisition and maintenance of tumor phenotype mithocondrial nonmetabolic phenomena associated with resistance to antitumor drugs. Thus it has been found that:. 1. This is the first report demonstrating that autophagy is mechanistically linked to the maintenance of tumor cells expressing high levels of CD44 and low levels of CD24, which are typical of breast cancer stem cells. 2. Our current findings provide new insight into how mitochondrial division is integrated into the reprogramming of the factors-driven transcriptional network that specifies the unique pluripotency of stem cells. 3. Autophagy may control the de novo refractoriness of HER2 gene-amplified breast carcinomas to the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab (Herceptin). Accordingly, treatment with trastuzumab and chloroquine, as antimalarial drug and inhibitor of autophagy, radically suppresses tumor growth in a tumor xenograft completely refractory to trastuzumab in a mouse model. Adding chloroquine to trastuzumab-based regimens may therefore improve. 13.

(37) SUMMARY outcomes among women with autophagy-addicted HER2-positive breast cancer. This is a very exciting and highly promising area of cancer research, as pharmacologic modulation of autophagy appears to augment the efficacy of currently available anticancer regimens and opens the way to the development of new combinatorial therapeutic strategies that will hopefully contribute to cancer eradication.. 14.

(38) RESUM Resum. L’autofàgia és un procés catabòlic i homeostàsic de degradació de components innecessaris o no funcionals de la cèl·lula que perllonga la supervivència cel·lular sota estrès a través de la degradació lisosomal dels components citoplasmàtics i el reciclatge d'aminoàcids i energia. L'autofàgia està íntimament involucrada en molts aspectes de la salut humana i les malalties, inclòs el càncer. A més, és una arma de doble fil en el procés tumorigènic, actuant com a supressor tumoral i protector de la supervivència de cèl·lules de càncer. No és té clar encara, quin és el paper que juga en les diferents etapes de la progressió del càncer i en la resposta al tractament. Per aquest motiu, una millor comprensió de la regulació de l'autofàgia i el seu impacte en el resultat del tractament potencialment permetrà la identificació de noves dianes terapèutiques en el càncer. En aquest treball, s’ha demostrat com la reprogramació del metabolisme energètic i l’autofàgia són esdeveniments moleculars funcionalment independents d’altres atributs claus en la malignització cel·lular i per tant, necessaris intrínsecament per permetre l’adquisició de les capacitats aberrants d’immortalitat, auto-renovació i diferenciació pròpies de les cèl·lules mare del càncer. A més, s’ha analitzat el procés d’autofàgia en l’adquisició i el manteniment del fenotip no metabòlic i mitoncondrial tumoral associat als fenòmens de resistència a fàrmacs antitumorals. Així doncs s’ha vist que:. 1. Aquest és el primer informe que demostra que l'autofàgia està mecànicament vinculat al manteniment de les cèl·lules tumorals que expressen alts nivells de CD44 i baixos nivells de CD24, que són típics de les cèl·lules mare del càncer de mama. 2. Els nostres resultats actuals proporcionen una nova visió de com la divisió mitocondrial s'integra a la xarxa de la transcripció impulsada per factors de reprogramació que especifica la pluripotència única de cèl·lules mare. 3. L'autofàgia pot controlar la refractarietat de novo de carcinomes de mama amb el gen HER2 amplificat per l'anticòs monoclonal trastuzumab (Herceptin). Per tant, el tractament de combinació amb trastuzumab i 15.

(39) RESUM cloroquina, com a fàrmac anti-malàric i inhibidor de l’autofàgia, suprimeix radicalment el creixement del tumor en un xenoempelt de tumor completament refractari a trastuzumab en un model murí. L’addició de cloroquina amb els règims amb trastuzumab pot, per tant, millorar els resultats en les dones amb càncer de mama HER2.. Aquesta és una àrea molt emocionant i molt prometedora de la investigació del càncer, com la modulació farmacològica de l'autofàgia sembla augmentar l'eficàcia dels règims contra el càncer disponibles en l'actualitat i s'obre el camí per al desenvolupament de noves estratègies terapèutiques combinatòries que s'espera que contribueixin a l'eradicació del càncer .. 16.

(40) RESUMEN Resumen. La autofagia es un proceso catabólico y homeostásico de degradación de componentes innecesarios o no funcionales de la célula, que prolonga la supervivencia celular bajo estrés a través de la degradación lisosomal de los componentes citoplasmáticos y el reciclaje de aminoácidos y energía. La autofagia está íntimamente involucrada en muchos aspectos de la salud humana y las enfermedades, incluido el cáncer. Además, es un arma de doble filo en el proceso tumorigénico, actuando como supresor tumoral y protector de la supervivencia de células de cáncer. No se tiene claro aún cuál es el papel que juega en las diferentes etapas de la progresión del cáncer y en la respuesta al tratamiento. Por este motivo, una mejor comprensión de la regulación de la autofagia y su impacto en el resultado del tratamiento potencialmente permitirá la identificación de nuevas dianas terapéuticas en el cáncer . En este trabajo, se ha demostrado como la reprogramación del metabolismo energético y la autofagia son eventos moleculares funcionalmente independientes de otros atributos claves en la malignización celular y por lo tanto, necesarios intrínsicamente para permitir la adquisición de las capacidades aberrantes de inmortalidad, auto-renovación y diferenciación propias de las células madre del cáncer. Además, se ha analizado el proceso de autofagia en la adquisición y el mantenimiento del fenotipo no metabólico y mitoncondrial tumoral asociado a los fenómenos de resistencia a fármacos antitumorales . Así pues se ha visto que:. 1.. Este es el primer informe que demuestra que la autofagia está mecánicamente vinculado al mantenimiento de las células tumorales que expresan altos niveles de CD44 y bajos niveles de CD24, que son típicos de las células madre del cáncer de mama .. 2.. Nuestros resultados actuales proporcionan una nueva visión de cómo la división mitocondrial se integra en la red de la transcripción impulsada por factores de reprogramación que especifica la pluripotencia única de células madre .. 17.

(41) RESUMEN 3.. La autofagia puede controlar la refractariedad de novo de carcinomas de mama con el gen HER2 amplificado por el anticuerpo monoclonal trastuzumab (Herceptin). Por tanto, el tratamiento de combinación con trastuzumab y cloroquina, como fármaco anti-malárico e inhibidor de la autofagia, suprime radicalmente el crecimiento del tumor en un xenoinjerto de tumor completamente refractario a trastuzumab en un modelo murino. La adición de cloroquina con los regímenes con trastuzumab puede, por tanto, mejorar los resultados en las mujeres con cáncer de mama HER2.. Esta es un área muy emocionante y muy prometedora de la investigación del cáncer, como la modulación farmacológica de la autofagia parece aumentar la eficacia de los regímenes contra el cáncer disponibles en la actualidad y se abre el camino para el desarrollo de nuevas estrategias terapéuticas combinatorias que se espera que contribuyan a la erradicación del cáncer.. 18.

(42) 1.. INTRODUCTION.

(43)

(44) INTRODUCTION 1. 1.1.. INTRODUCTION Cancer. Cancer and tumor development is a cellular disease characterized by excessive and uncontrolled growth of a cell or group of cells which invade and damage tissues and organs of the body and can even lead to death (Bertram 2000). With this disease, we are facing one of the most frequent causes of death, taking second place when considering worldwide figures (more than 7 million deaths per year), behind heart disease or cardiovascular disease. It ranks first if we consider only the developed countries (Table 1). The incidence of cancer has increased in recent decades (responsible for 26.6 % of total deaths in developed countries), but it must also be said that the health care in these countries has improved due to advances in early diagnosis and therapeutic treatments. So the mortality rate has decreased but is still too high with over 2 million deaths each year in developed countries alone. According to estimates by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), in 2008 there were 12.7 million new cancer cases worldwide, of which 5.6 million were produced in economically developed countries and 7.1 million in countries less economically developed. Estimates corresponding to the total number of deaths from cancer in 2030, predict 21.4 million new cancer cases and 13.2 million cancer deaths simply due to growth and aging of the global population, and a reduction in infant mortality and deaths from infectious diseases in the less developed countries. Despite the pessimism of these data, the mortality rate has been shrinking over the years, mainly due to improvements in early diagnosis and treatment of disease. As I mentioned, it is expected that the incidence of cancer will increase significantly, because more new cases are diagnosed each year. Although it is also true that thanks to cancer research, pharmaceutical and early diagnosis are increasing survival in some cancers very considerably, for example in breast cancer.. 21.

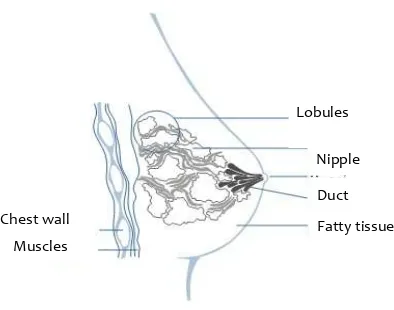

(45) INTRODUCTION However there is still much work to do and to improve, because not all the cancer patients are able to survive (Bosetti, Bertuccio et al. 2011). Rànquing. Causa de mort. Nombre de morts*. % total de morts. 1. Càncer. 2,154. 26.6. 2. Malalties cardiovasculars. 1,563. 19.3. 3. Malalties cerebrovasculars. 757. 9.4. 4. Infeccions respiratòries. 305. 3.8. 5. Malaltia respiratòria obstructiva crònica. 285. 3.5. 6. Diabetis mellitus. 221. 2.7. 7. Nefritis i nefrosis. 126. 1.6. 8. Suïcidi. 118. 1.5. 9. Cirrosis del fetge. 116. 1.4. 10. Accidents de tràfic. 114. 1.4. 11. Condicions perinatals. 35. 0.4. 12. VIH/AIDS. 20. 0.2. 13. Tuberculosi. 15. 0.2. 14. Malalties diarreiques. 14. 0.2. 15. Malària. 0. 0. 8,095. 100. TOTAL. Table 1. Main causes of death in developed countries (2008), data extracted from the report of the American Cancer Society. * Number of deaths in thousands.. 1.2.. Breast cancer. Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women, with an incidence of 22.9% (Globocan 2008, IARC 2010). Worldwide in 2008 there were 1,383,500 new cases and a total of 458.400 deaths from breast cancer (GLOBOCAN 2008). Among cancers in Spain, breast cancer is one of the most common with 22,000 new cases per year, that is, about 30% of total tumors females (Spanish Association Against cancer, AECC). Breast cancer, as it is known, starts or originates in the tissue of the mammary gland (Figure 1A). It is a tumor that can invade other tissues and of the patient's body. 22.

(46) INTRODUCTION such as lung, bone, liver, brain and/or the other breast (Figure 1B). It affects mostly women, but in 1% of cases it can also affect men. Specifically, it can originate in different areas of the mammary gland: the pipes or ducts (in charge of transporting milk), the lobules (where milk is produced) or, in some cases, in the intermediate tissue (Figure 2). A). B). Metastasis. Figure 1. A) Formation of a tumor in the mammary gland. B) Organs where the breast cancer can become metastatic: Brain, lung, liver, bone and in the same or the other breast.. Among the risk factors that increase the probability of developing breast cancer it was found that about 5-10% of breast cancer cases are hereditary. The two most common mutations in breast cancer are BRCA1 and BRCA2. In addition, other risk factors have been described as ethnicity, breast density, obesity, hormone therapy, alcohol and tobacco, etc.. Lobules Nipple Duct Chest wall. Fatty tissue. Muscles. Figure 2. Anatomy of the mammary gland.. According to the histology of breast cancer, including the most common, we can identify different types of breast tumors: a) lobular carcinoma in situ, b) Ductal 23.

(47) INTRODUCTION carcinoma in situ, c) infiltrating lobular carcinoma or invasive d) infiltrating ductal carcinoma or invasive. The classification of breast cancer varies according to the criteria evaluated in tumors. According to the characteristics of the tumor, sensitivity receptors as prognostic factors and the degree of involvement has been awarded the following classification (Table 2), which allows us to adapt the treatment given to each patient, thus contributing to the survival and improvement quality of life.. Types of breast cancer. Molecular characteristics. Proliferative capacity. State of diferenciation. Prognosis. Other. Luminal A. ER+ and/or PR+ and HER2-. Low. High. Good. Hormonal response. Associated with increasing age. Luminal B. ER + and/or PR+ and HER2+. High. High. Bad. Similiar to the luminal subtype A. More frequent ER + and PR -. ErbB2+. ER- i PR- and HER2+. High. Intermedium. Bad. Risk in women under 40. Triple negative basal. ER-, PR- and HER2-, CK5/CK6+ and/or HER1+. High. Low. Bad. Highly mitotic ratio. Risk ages less than >40 years. Normal breast tumor. Table 2. Table representing the main features of different types of breast cancer.. Thus, breast cancer can be classified into five different types (Perou, Sorlie et al. 2000, Sorlie, Perou et al. 2001, Herschkowitz, Simin et al. 2007, Prat, Parker et al. 2010). One of the most common types is HER2+ breast cancer, which accounts for 2024.

(48) INTRODUCTION 30% of total breast cancers cases (Slamon, Clark et al. 1987). Keep in mind this is one of the most aggressive types and with worse prognosis for the patient if we compare with the other types (Slamon, Godolphin et al. 1989) and often only between 15-35% of patients with HER2+ breast cancer respond to treatment with monoclonal antibody target, trastuzumab (Salomon, Brandt et al. 1995). In addition, approximately 70% of patients that respond to therapy become resistant after one year of treatment. This indicates the high rate of primary resistance to therapy with monoclonal antibody. Therefore, the development of drug resistance is now a major clinical problem (Nahta and Esteva 2003, Bianco, Troiani et al. 2005, Nahta and Esteva 2006, Nahta and Esteva 2006, Nahta, Yu et al. 2006, Vazquez-Martin, OliverasFerraros et al. 2009).. 1.3.. Cancer cells characteristics The process of tumor formation involves the accumulation of alterations of. the cells that form the tumor in question. The causes of cancer can be of two types: a) errors in the endogenous cellular processes and b) external agents that can alter genes, including chemicals with 80-90% of cases (eg. smoking), physical agents 5% of cases (ionizing and ultraviolet radiation) and finally because of a virus responsible for some types of cancer such as HPV -16, HPV -18 and others, with 5-10% of cases (Bogenrieder and Herlyn 2003). A multicellular organism is composed of many types of cells that grow and divide in an organized manner. Cell multiplication is a very well regulated process and responds effectively to the organism's specific needs of the moment. The cells send, receive and interpret a complex system of signals that serve as social control, telling each of them how and when they must act. In short, each cell behaves in a socially responsible way: stopping, dividing, differentiating or dying for the sake of the body. Thus, the possible molecular disturbances that disrupt this harmony cause serious problems for multicellular society.. 25.

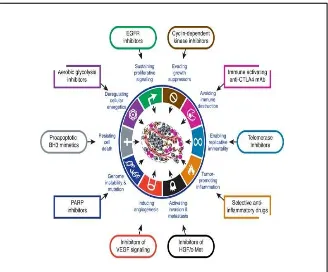

(49) INTRODUCTION During the formation and tumor progression should call different molecular processes that take place. The tumor characteristics and behaviors towards normal cells are described by Hanahan and Weinberg (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011), and have been accepted by the scientific community, as having the following qualities (Figure 3): • Independence from external signals that regulate cell proliferation • Escape from programmed cell death or apoptosis • Avoidance of suppressing cell growth • Activation of invasion and metastasis • Acquisition of replicative immortality • Maintenance of angiogenesis • Inflammation that promotes tumor growth • Avoiding immune destruction • Genome instability and mutations • Reprogramming of energy metabolism. 26.

(50) INTRODUCTION. Figure 3. Schematic representation of what happens in a cell that becomes a tumor. Figure from (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011).. The development of a whole tumor or uncontrolled cells (carcinogenesis) is a process in which the cell acquires all the features mentioned. These basic features of general tumor cells, survival and growth of a tumor in metabolically different conditions compared to normal healthy tissue (Tennant, Duran et al. 2009). Among the changes required for a normal cell that is transformed into tumor is migratory capacity, also known as metastasis, that allows cells to invade and affect other tissues and organs of the body (Langley and Fidler 2007). In order to understand and to study the carcinogenesis we must consider the complexity of the disease, which is reflected with its morphological variability and prognosis of tumors and the large number of oncogenic molecular alterations described, which needless to say will increase with discoveries of new molecules or new functions of molecules already known (Jemal, Center et al. 2010). In this study we focused on the reprogramming of energy metabolism and autophagy especially. Reprogramming has been considered as a consequence of energy metabolism or adaptation to other cellular changes, however it is now considered a mechanism to target in anti-tumor therapies (White and DiPaola 2009). 27.

(51) INTRODUCTION Indeed, reprogramming of energy metabolism was not regarded as an essential feature as those described by Hanahan and Weinberg in their first study in 2000 (Hanahan and Weinberg 2000). However, it was added in the 2011 by the same authors (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011). There are many types of cancer, but they all start because of the uncontrolled growth of cells. The tissue where the tumor starts is the name given to the cancer, regardless of where the tumor metastasizes. For example, breast cancer that spreads to the liver is still breast cancer, not liver cancer. Likewise, prostate cancer that has invaded the bones is called metastatic prostate cancer, not bone cancer. Different types of cancer can behave very differently, and it is for this reason that patients with different types of cancer receive treatment directed at their own cancers. Not all tumors are cancerous and these are known as benign tumors. Benign tumors can cause problems since they can grow and cause much pressure on other healthy tissues and organs of the body, but rarely threaten the patient's life. However, these tumors can not grow into other tissues, for this reason, they can not spread to other parts of the body and therefore can not metastasize.. 1.4.. Cancer stem cells. Within the scientific community there is currently a lot of controversy on the origin of the cell that initiates carcinogenesis, or tumor process. We found two very different hypotheses about it. In classical stochastic theory it is believed to be a differentiated somatic cell that, with the accumulation of mutations during replication, is transformed and acquires the ability to proliferate indefinitely and generate a tumor. However in the more current theory of cancer stem cells it is a stem cell tumor (CSCs, also called cell tumor initiator or propagating cell cancer) coming from an adult stem cell or mesenchymal cell with properties of a stem cell that, due to mutations or environmental factors, acquires self renewal, divides uncontrollably, and differentiates to form a tumor (Jordan 2009, Rosen and Jordan 2009). Therefore, the classical theory of tumor growth is a random process not 28.

(52) INTRODUCTION organized in which all cells can contribute equally (Figure 4A). Moreover, in the CSCs model are the tumor origin (Figure 4B). The pioneering study that detected CSCs was made by Dick et al. (Dick, Bhatia et al. 1997), which isolated stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia (Bonnet and Dick 1997). It was not until 2003 when they detect such stem cells in solid tumors, particularly breast cancer (Al-Hajj, Wicha et al. 2003). In classical theory, most of the cells that form the tumor have the ability to proliferate indefinitely and generate new ones, while in the stem cell theory, only CSCs can proliferate indefinitely, causing differentiated cells and forming new tumors or metastases, the remaining cells would be considered "children" without renewing capacity (Fillmore and Kuperwasser 2008). Since the 70s, a new paradigm emerged with respect to the origin of epithelial malignancies (Hamburger and Salmon 1977). A growing number of studies have begun to establish unequivocally the existence of different molecular fractions of tumor cells that not only contribute to the phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of various types of cancer, but are also able to survive treatment with hormones, radiation, chemotherapeutic agents and molecularly targeted drugs (Li, Lewis et al. 2008, Creighton, Li et al. 2009, Krause, Yaromina et al. 2011, Vazquez-Martin, OliverasFerraros et al. 2012). Because this subpopulation of stem cells, called tumor (CSCs), have the unique ability to cause tumor recurrence after surviving cancer treatments, it is reasonable to suggest that they are responsible for the clinical failure of most oncology therapies currently available (Kakarala and Wicha 2008). As a corollary of this situation, we consider that the increase in the response rate of the majority of human tumors to standard therapy necessarily requires a combination of a therapy to reduce tumor volume (eg. conventional chemotherapy with stem cells not cancerous) and the new anti-CSC therapy (Liu and Wicha 2010). Although conceptually attractive, the process of discovering and validating new drugs specifically targeted against cancer stem cells require a thorough characterization of the fundamental mechanisms responsible for the molecular characteristics of CSCs, including: immortality, self-renewal, and cross-resistance to 29.

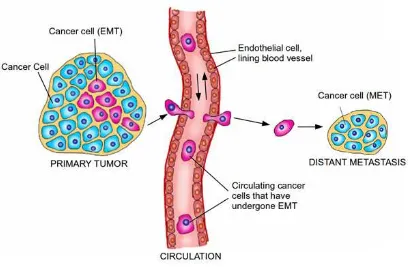

(53) INTRODUCTION treatments. On the one hand, it remains to be seen whether all the CSCs are resistant to therapeutic agents against cancer or if there are specific phenotypes of resistance to certain pharmaceutical agents, which are causally associated with functional changes in specific signaling pathways that are regulated aberrant form on CSCs. Moreover, the phenotype of resistance to multiple pharmaceutical agents who possessed by CSCs may have its origin in the simultaneous alteration of several intracellular. signaling. cascades. and/or. interactions. with. the. extrinsic. microenvironment (eg. the niche of CSCs) (Li and Neaves 2006, Borovski, De Sousa et al. 2011, Cabarcas, Mathews et al. 2011). Perhaps most importantly, it is not known if there is a single molecular mechanism shared between CSCs and all carcinomas and/or different sub-types of a single tumor type.. Figure 4. Origin of breast cancer; A) in the traditional theory most tumor cells have the ability to proliferate indefinitely and generate new tumors, while B) in the theory of stem cell, only CSCs can proliferate indefinitely and generate new tumors. Figure from (Reya, Morrison et al. 2001).. Cancer is usually initiated by damage or change in the cell, leading to deregulation of proliferation that ultimately leads to the formation of a tumor. As these tumor cells proliferate, the tumor is becoming bigger and requires the creation of new blood vessels so that nutrients and oxygen reach all the cells that form, a process known as angiogenesis. Finally, the process culminates with the cancer or tumor spreading the disease to other organs and tissues of the body, called metastatic process (Figure 5).. 30.

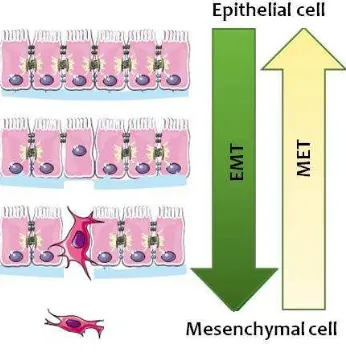

(54) INTRODUCTION. Figure 5. Tumor process stages: Carcinoma in situ, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis.. Metastasis can occur either by collective migration of epithelial tumor cells (Rorth 2009) or migration of individual cells that have acquired properties of or are mesenchymal stem cells (Lopez-Novoa and Nieto 2009). In the first case, the spread occurs via the lymphatic vessels (Giampieri, Manning et al. 2009), while the second uses the blood vessels for dissemination (Condeelis and Segall 2003, Wyckoff, Wang et al. 2004). We also found disagreement within the scientific community on whether origin of metastatic cells are stem cells or mesenchymal: either come from the small subpopulation of stem cells that are intrinsic to cancer of the heterogeneous group of cells forming tumors or cells that have acquired different properties of stem cells due to mutations or evolutionary processes such as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (Mathews, Alexander et al.).. 1.5.. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Epithelial- mesenchymal transition is a fundamental process in the remodeling of tissues during embryonic growth and tissue regeneration. It is characterized by a dissolution of the joints between adjacent epithelial cells and loss of apico-basolateral polarity, an increase in the capacity degradation of extracellular matrix and cytoskeleton modification of epithelial cells, leading to result mesenchymal cells with migratory and invasive capacities (Figure 6) (Acloque, Adams et al. 2009, Kalluri and Weinberg 2009). In pathological conditions described for example in progress and tumor invasion, while the reverse transition, mesenchymal-epithelial (Klionsky, Abdalla et al.) has been observed in the last stages of metastatic colonization. During embryogenesis EMT occurs during gastrulation, neural crest formation and the formation of organs such as heart valves, palate and skeletal muscles 31.

(55) INTRODUCTION (Micalizzi, Farabaugh et al. 2010). In these processes, the cells undergo transition and are recruited to specific sites in the developing embryo where they differentiate by the reverse process (epithelial-mesenchymal transition, MET) to form epithelial tissues in distant places. In normal physiological conditions, this process also occurs during tissue regeneration, after damage or injury, the epithelial cells are dedifferentiated by EMT to be able to regenerate damaged cell types (Thiery, Acloque et al. 2009). This process was recently described as occurring in certain diseases such as fibrosis and cancer (Lopez-Novoa and Nieto 2009), but being a transient and reversible phenomenon, it makes their study difficult.. Figure 6. Cellular changes during EMT. Loss of junctions between adjacent epithelial cells, loss of apicobasolateral polarity, degradation of the extracellular matrix and cytoskeleton modification of cells resulting in mesenchymal cells.. Today it is considered that there are three different subtypes of EMT as functional consequences generated and its biological context. These subtypes are: EMT development (or Type I), EMT fibrosis or regeneration of wounds (or Type II) and EMT cancer (or type III) (Kalluri and Weinberg 2009). In addition, specific markers have been described for each type, as well as other general for all subtypes (Zeisberg and Neilson 2009). In this study we focus on the involvement of EMT in cancer, which confers aggressive properties like improvement of mobility or migration, invasion and metastasis (Figure 7). EMT features were detected in several types of cancer such as breast cancer (Trimboli, Fukino et al. 2008), ovarian (Vergara, Merlot et al. 2010), 32.

(56) INTRODUCTION colon (Brabletz, Hlubek et al. 2005) and esophagus (Usami, Satake et al. 2008). Specifically, aggressive breast cancers showed phenotypic characteristics typical of the process, such as a reduction of epithelial markers (E-cadherin , occludins, claudins, desmoplakins and epithelial cytokeratins) and increased mesenchymal markers (eg. vimentin, Smooth muscle actin, fibronectin and N-cadherin) (Thiery, Acloque et al. 2009).. Figure 7. Involvement of the EMT and MET in the development of cancer. Buddhini Samarasingh.. At the cellular level, the mechanisms that regulate EMT in physiological and pathological situations are very similar. Among the signals that induce EMT there are those generated by a state of hypoxia inducing factors secreted to the extracellular matrix or the cells themselves as TGF- β, and receptor ligands with tyrosine kinase activity and own receivers (among which we find ErbB2) (Jenndahl, Isakson et al. 2005, Hardy, Booth et al. 2010, Said and Williams 2011). Specifically, activation of these pathways can cause an increase in the activity of the transcriptional repressor Snail, ZEB and TWIST which in turn represses the expression of cell adhesion molecules such as E- cadherin and thus cause EMT (Mimeault and Batra 2007). Keep in mind that not all contexts are able to induce EMT, but the achievement of this process depends 33.

(57) INTRODUCTION on the dimers formed of signaling pathways activated effector and as the signal generated affects cell junctions (Feigin and Muthuswamy 2009). EMT and the formation of mesenchymal cells with features of CSC are also regulated by several miRNAs, among which is the family of miR200, which regulates transcription factors such as Twist1, Snail1, ZEB1 and ZEB2 (Gregory, Bert et al. 2008). Among the major transcription factors that regulate EMT (Table 3), there are family members Snail and ZEB -structured zinc fingers and members of the family of basic - helix - turn - helix as TWIST. All of them bind to E boxes of the promoters of target genes regulating and repressing their expression. Among others, the CDH1 gene promoter involves the inhibition of the expression of E-cadherin and triggers EMT (Nieto 2002, Yang, Mani et al. 2004). Currently, there are studies that show that in addition to inducing the EMT, these transcription factors are also involved in proliferation, cell survival and tumor progression (Peinado, Olmeda et al. 2007).. Epithelial cell. Mesenchymal cell. Polarity. Yes. No. Structures of cell adhesion. Yes. No. Mobility. No. Yes. Expression of E-cadherin. High. Low. Expression of vimentin. Low. High. Drug resistance. Low. High. Multipotency. No. Yes. Table 3. Differential characteristics between epithelial and mesenchymal cells.. In epithelial tumors, formed by differentiated cells, under certain external stimuli that can be generated by the tumor or own cells that form can be carried out EMT. Tumor cells that have undergone EMT are dedifferentiated resulting in mesenchymal cells with properties of CSC (Mani, Guo et al. 2008). These cells allow the progression of the disease, because they are multipotent cells that can redifferentiate in another cell type other than allowing the creation of vessels within the tumor (angiogenesis), 34.

(58) INTRODUCTION or due to their increased mobility and resistance, can migrate and travel through the bloodstream until it implemented a new niche which can be redifferentiated generating a secondary or metastatic epithelial tumor (which is why they are also called tumor- initiating cells). EMT not only confers aggressive cancer, but also confers resistance to treatment. Specifically, it has been shown that tumors that have undergone EMT are more resistant to conventional therapy such as oxaliplatin, paclitaxel and radiation among others (Hiscox, Morgan et al. 2004, Kajita, McClinic et al. 2004, Hiscox, Jiang et al. 2006, Yang, Fan et al. 2006, Kajiyama, Shibata et al. 2007, Kurrey, Jalgaonkar et al. 2009). In addition, eliminating the expression of Twist or forced expression of miR-200c (events that negatively regulate EMT) achieves a response in the resistant cells (Cochrane, Spoelstra et al. 2009, Li, Xu et al. 2009). The acquisition of a mesenchymal phenotype can also prevent senescence induced by oncogenes (Ansieau, Bastid et al. 2008). Finally, the EMT may facilitate immune evasion by regulating immune responses directly, which contributes to the aggressiveness of the tumor (Kudo-Saito, Shirako et al. 2009). In summary, the EMT phenotype contributes to the acquisition of stem cell tumor resistance to chemotherapy and senescence, immune evasion, local spread of tumor cells and induction of gene expression profile type baseline. Therefore, presence of the EMT phenotype, favors the progression of the disease towards a more invasive and metastatic stage. Some of the distinguishing characteristics between the epithelial and mesenchymal cells are polarity, the presence of structures of cell adhesion, mobility, the expression of E-cadherin and vimentin, drug resistance and pluripotency (Micalizzi, Farabaugh et al. 2010). Here we cited the most relevant transcription factors, all inducing EMT (Ouyang, Wang et al. 2010):. ✓ TWIST ✓ SNAIL1 ✓ SLUG/SNAIL2 35.

(59) INTRODUCTION. ✓ ZEB1 ✓ ZEB2 ✓ FOXC2 ✓ LBX. 1.6.. Tumor metabolism. The difference in potential that malignant tumor cells possess versus normal cells, while it is not pronounced includes metabolic changes that allow them to supply the high demand for energy and biosynthetic necessary to maintain the high rate of cancer cell proliferation (Kroemer and Pouyssegur 2008, Samudio, Fiegl et al. 2009, Samudio, Harmancey et al. 2010). Therefore, tumor cells have adapted to acquire a phenotype to reprogram the metabolism. This metabolic adaptation by the tumor is characterized: a high glycolysis even in the presence of oxygen (Warburg effect), activation of biosynthetic pathways (obtaining nucleic acids and lipids) and a high consumption of glutamine (to generate ATP and lactate) among others (Kamarajugadda, Stemboroski et al. 2012). The normal cells usually degrade glucose to form pyruvate via glycolytic. In aerobic conditions, the pyruvate reaches the mitochondria where it continues its metabolism through the tricarboxylic acid cycle or Krebs cycle. This process generates a large amount of reducing power capable of electrons in the electron transport chain or respiratory chain to generate energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in the process known as oxidative phosphorylation. Through this metabolic process, cells consume oxygen and glucose and end up creating carbon dioxide (CO2) and water. In anaerobic conditions, the normal cells can survive transforming pyruvate into lactate, a process known as anaerobic glycolysis. High concentrations of lactate are toxic to the cell. Oxidative phosphorylation is a much more efficient mechanism for obtaining energy because it generates 36 molecules of ATP per molecule of glucose while anaerobic glycolysis generates only 2 ATP molecules per each molecule of glucose.. 36.

(60) INTRODUCTION The first distinguishing metabolic level characteristics for tumor cells, described by Otto Warburg in 1924, is its high rate of conversion of glucose to lactate even under anaerobic conditions (Govardhan, Ramyasri et al. 2011), also known as Warburg effect (Figure 8). A study that was carried by Fantin and his collaborators showed that some tumor cells still retain the capacity to produce ATP by oxidative phosphorylation but still "choose" to promote anaerobic glycolysis (Fantin, St-Pierre et al. 2006).. Figure 8. Warburg effect vs. anaerobic glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation.. The Warburg effect offers several advantages to the tumor cell. First, it lets out energy more quickly than the more efficient oxidative phosphorylation and it increases the rates of biosynthesis routes (Grivennikov and Karin 2010). Secondly, it seems that reduces the oxidative stress using the mitochondria to prevent apoptosis, since the respiratory chain is the main generator of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can lead to programmed cell death. In addition, lactate production causes the acquisition of other characteristics of malignant cells, such as acidification of the environment and consistent peritumoral tumor growth (Gillies, Robey et al. 2008), activation of angiogenesis (Shi, Le et al. 2001), acquisition of invasiveness and metastasis (Walenta and Mueller-Klieser 2004) and inhibition of the immune response (Mendler, Hu et al. 2012).. 37.

Figure

Documento similar

For more than 20 years, our group has under- taken molecular studies in planarians to charac- terize a large number of developmental regula- tory genes during regeneration, with

These post-natal populations have mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-like qualities, namely the capacity for self-renewal, the potential to differentiate into multiple lineages,

Although they were the main population, DPPSCs coexisted in culture with other cell types, such as mesenchymal stem cells from the dental pulp (DPMSCs), due to the lack of a

In order to test if tEVs CSC preferentially interact with specific immune cell subsets, we challenged mice with mEER tumor cells carrying the ALDH1A1:CD63-eGFP or the

Metabolic, inflammation, bacterial translocation, immunological and nutrition markers in Supple- mented Mediterranean Diet group (SMD) and control group, Table S3: Key food items

Likely in concert with LE/Lys-Chol transporters, several Rab GTPases coordinate LE/Lys-Chol transport to cellular sites with critical roles in cancer cell growth and motility

When we analyzed the survival of patients who underwent ASCT, patients with PPs who received ASCT had similar OS than patients without plasmacytomas (median: 98 vs 113 months, p

antiproliferative activity of these extracts (leaf and flower) against the three-cancer cell lines tested (HepG2, HeLa, and MCF-7), although the viability of these cells was