and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or

licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the

article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or

institutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are

encouraged to visit:

ContentslistsavailableatSciVerseScienceDirect

Ecological

Modelling

j ou rna l h o m e pa ge :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / e c o l m o d e l

Modelling

the

spatio-temporal

pattern

of

primary

dispersal

in

stone

pine

(

Pinus

pinea

L.)

stands

in

the

Northern

Plateau

(Spain)

Rubén

Manso

a,∗,

Marta

Pardos

a,

Christopher

R.

Keyes

b,

Rafael

Calama

a aDpto.SelviculturayGestiónForestal,CIFOR-INIA,Ctra.LaCoru˜nakm7.5,28040Madrid,SpainbDepartmentofForestManagement,CollegeofForestry&Conservation,UniversityofMontana,Missoula,MT59812,USA

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory: Received19April2011 Receivedinrevisedform 21November2011 Accepted25November2011

Keywords: Inversemodelling Fecundity Crowneffect Seedlimitationindexes Climatecontrol Regenerationfellings

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Naturalregenerationinstonepine(PinuspineaL.)managedforestsintheSpanishNorthernPlateauis notachievedsuccessfullyundercurrentsilviculturepractices,constitutingamainconcernforforest managers.Wemodelledspatio-temporalfeaturesofprimarydispersaltotestwhether(a)presentlow standdensitiesconstrainnaturalregenerationsuccessand(b)seedreleaseisaclimate-controlledprocess. Thepresentstudyisbasedondatacollectedfroma6yearsseedtrapexperimentconsideringdifferent regenerationfellingintensities.Fromaspatialperspective,weattemptedalternateestablishedkernels underdifferentdatadistributionassumptionstofitaspatialmodelabletopredictP.pineaseedrain.Due toP.pineaumbrella-likecrown,modelswereadaptedtoaccountforcrowneffectthroughcorrectionof distancesbetweenpotentialseedarrivallocationsandseedsources.Inaddition,individualtreefecundity wasassessedindependentlyfromexistingmodels,improvingparameterestimationstability.Seedrain simulationenabledtocalculateseeddispersalindexesfordiversesilviculturalregenerationtreatments. Theselectedspatialmodelofbestfit(Weibull,Poissonassumption)predictedahighlyclumpeddispersal patternthatresultedinaproportionofgapswherenoseedarrivalisexpected(dispersallimitation) between0.25and0.30forintermediateintensityregenerationfellingsandover0.50forintensefellings. Todescribethetemporalpattern,theproportionofseedsreleasedduringmonthlyintervalswasmodelled asafunctionofclimatevariables–rainfallevents–throughalinearmodelthatconsideredtemporal autocorrelation,whereasconeopeningtookplaceoveratemperaturethreshold.Ourfindingssuggest theapplicationoflessintensiveregenerationfellings,tobecarriedoutafteryearsofsuccessfulseedling establishmentand,seasonally,subsequenttothemainrainfallperiod(latefall).Thisschedulewould avoiddispersallimitationandwouldallowforacompleteseedrelease.Thesemodificationsinpresent silviculturepracticeswouldproduceamoreefficientseedshadowinmanagedstands.

© 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Pinuspinea is an essential species of Mediterranean

ecosys-temsthatprovidesimportanteconomicbenefitstolocalpopulation fromitsedibleseedproductionandtimberproduction.Inaddition, thespeciesplaysavaluableecologicalroleasitsnatural distribu-tionoccupieschallengingsitesthatexhibitgeneralMediterranean weatherconditions,continental wintersand highly sandysoils, wherefewarborealspeciespersist.Suchanenvironmentcanbe oftenfoundthroughouttheSpanishNorthernPlateau(Pradaetal.,

1997), which accounts for more than 50,000ha of indigenous

∗Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+34913471461;fax:+34913476767. E-mailaddresses:manso.ruben@inia.es,rmgforestal@hotmail.com

(R.Manso),pardos@inia.es(M.Pardos),christopher.keyes@cfc.umt.edu(C.R.Keyes), rcalama@inia.es(R.Calama).

P.pineaforests.Thesestandshavebeenmanagedforoveracentury

throughmodernsilviculturetechniques.

P.pineanaturalregenerationhasbecomeaprimaryconcernfor

forestmanagement.LikeotherMediterraneanspecies(e.g.species ofgenusQuercus),naturalregenerationiscommonlyunsuccessful undercurrentlyappliedsilviculturalsystems(seedtreemethod, and,increasingly,shelterwoodmethod),whichleadtolow den-sitiestooptimizeconeproductionpertree.Regenerationfellings derivedfromthesetreatmentsproduceeven-agednon-coetaneous standsastheyintendtoimitatenaturalforestdecayleading gen-erallytothesestructures(Schütz,2002).Severalfactorshavebeen notedasdeterminantsofthisregenerationfailure,including: cli-mate,andspecificallyseveresummerdroughtsandhighsummer temperaturesthatleadtoestablishmentfailure;mastinghabitand lackofsynchronywithregenerationfellingsandadequateyears forseedlingestablishment;intensiveconeharvesting,resultingin depauperateseedbanksprior toregenerationfelling;long rota-tions,inducingpoorseedcropsduringtheregenerationperioddue

totreevigourdecline;thespecies’ gravity-basedseed dispersal strategy,resultinginpatchyseeddistribution;andpost-dispersal seedpredation(CalamaandMontero,2007;Barbeitoetal.,2008;

Mansoetal.,2010).

The study of primary seed dispersal spatial patterns has focused on understanding the general mechanisms that con-trolfundamentalpopulationdynamics(Clarketal.,1998,1999b;

Nathan et al., 2002; Levin et al., 2003; Muller-Landau et al.,

2008; Martínezand González-Taboada, 2009),or their

ecologi-cal consequencesin localcircumstances (Ordó ˜nez et al., 2006;

Santoset al., 2006; Debain et al., 2007; Gómez-Aparicio et al.,

2007;Sagnard et al., 2007). Similarly, moststudies aboutcone

openingprocesseshavemainlyaimedtotesttherelative impor-tanceofpyriscenceandxeriscence strategiesfromanecological perspective (Nathan et al., 1999, 2000), evolutionary perspec-tive(Tapiasetal.,2001)andstructuralperspective(Nathanand

Ne’eman,2004).Withfewexceptions(suchasTsakaldimi etal.

(2004)or Ganatsas and Thanasis (2010)),little effort hasbeen

undertaken to apply the valuable information generated from ecologicalstudiestoinformpracticesofpromotingnatural regen-eration.

Thedensityofseedsdepositedinaparticularlocationwithina standisafunctionofstandstockingandthespatialarrangement oftrees(source),andofseedproductionandthecapacityforseed dispersaloverlongdistances(Clarketal.,1998).Providedthatthe latterisaseriousconstraintforcolonizationinP.pinea,duetothe species’largewinglessseed(Magini,1955),adeeperknowledge ofseeddispersalspatialtraitscanofferessentialinformationwith referencetothesuitabilityofcurrentdensitiesinstandsafterseed fellingsfornaturalregeneration.Lowstockingspromoteahigher coneproductionpertree(Calamaetal.,2008)butmayresultin aseedarrivallimitation(dispersallimitation).Ontheotherhand, densestandslargelyfavoranevendistributionofseedsbutmay contributetoinsufficientseedproduction(seedlimitation). Opti-maldensitieswouldleadtoacompromisebetweenbothsituations, withacceptabletrade-offsinbothseedproductionandseed disper-sal.Becauseconeopeningisrelatedtophysicalvariables(Dawson etal.,1997),accuratepredictionsofseedreleaseratesbasedon cli-matevariableswouldallowforoptimizedtemporalregeneration fellingschedules.

In thepresentstudy,anestablishedmethodology toanalyze thespatialpatternofseeddispersalwasused.Themethodology, introducedbyRibbensetal.(1994)tostudythespatialdistribution ofseedlingsfromseedsourcelocations,utilizesinversemodelling proceduresinordertoestimatethesummedseedshadowfrom datacollectedinaseedtrapexperiment.Althoughbroadlyapplied (Clarketal.,1998,1999b;Uriarteetal.,2005;Debainetal.,2007;

Sagnardetal.,2007;Nanosetal.,2010),theapproachisnot

with-outcontroversy,especiallywithregardtotheexperimentaldesign (Clarketal.,1999a).Recently,comparisonscarriedoutwithseed dispersalkernelsattainedfromgeneticanalysisdemonstratedthat traplocationcandramaticallybiasparameterestimation

(Robledo-ArnuncioandGarcía,2007).Furthermore,amorestableandreliable

estimationisachievedifthefittingprocessisindependentofthe fecundityparameter.Ithasalsobeenarguedthatother consider-ations,suchasthebiasintroducedbyimmigrantseeds(i.e.from nomapped sources), should be taken into account (Jones and

Muller-Landau,2008).ForP.pinea,however,therelativelyshort

dispersaldistance(Rodrigoetal.,2007)andtheavailabilityof exist-ingmodelstoindependently estimateseed production(Calama

etal.,2008)severelyreduceparameterizationstabilityproblems,

andimmigrantseedsoccurrencecanbesafelyconsidered negligi-ble.Inaddition,potentialbiasderivedfromtraplocationcanbe minimizedwithasensibletrapdeploymentinordertoobtaina largerrepresentationofcritical(andmorerelevant)dispersal dis-tances.

Alternativekernelsestimatedbyinversemodellinghavebeen recentlyproposedbasedondifferentassumptionsthatdeal bet-terwithspeciesspecificdispersalfeatures.Mechanisticapproaches (GreeneandJohnson,1989;StoyanandWagner,2001;Wrightetal.,

2008)werespecificallydevelopedtomodelwinddispersedspecies

kernels. From a non-mechanistic perspective, different variants of the Weibull distribution have been assessed (Ribbens et al.,

1994; Clark et al., 1998),while improvementson those

meth-ods were attained to manage its specific rigid behavior (Clark

etal.,1999b;BullockandClarke,2000).Eventually,otherempirical

approachescomprisinggeneticprocedureshavebeendevelopedto obtainmoreaccuratepredictions(González-Martínezetal.,2006;

Robledo-ArnuncioandGarcía,2007).Forourstudy,wetestedand

compared theperformance of alternative models,sensu Debain

etal.(2007),selectedaccordingtoP.pineaspecificdispersal

syn-drome,asausefulprotocoltoachievethebestfitand,consequently, acorrectinterpretationofthephenomena.Additionally,from sim-ulationsassessedthroughthemodelofbestfit,wecalculatedand comparedsourceabundanceanddispersallimitationindexvalues (Clarketal.,1998;Muller-Landauetal.,2002)underP.pinea’stwo mostcommonregenerationfellingsystemsandacontrolstand(i.e. priorfellings).

Themainaimsofthepresentworkweretounderstand,model andpredictthespatio-temporalpatternsoftheprimarydispersal

inP.pineamanagedstandsintheSpanishNorthernPlateau.The

purposewastoidentifythelikelybottlenecksoccurringduringthe firststepofthenaturalregenerationprocess.Ourhypotheseswere (a)thatcurrentstanddensitiesatrotationageinmanagedP.pinea forestsconditionnaturalregenerationsuccess,and(b)thereexists a climatecontrolonthetemporal patternof primarydispersal, similartothephenomenondrivingconeproduction(Mutkeetal.,

2005a;Calamaetal.,2011).Ourfindingswillserveasanessential

toolforforestmanagersattemptingtoachievesatisfactorynatural regenerationofP.pinea.

2. Materialsandmethods

2.1. Studysite

The study site is located at 700m a.s.l. in a representative

P. pinea stand onthe flat sandy soils of the Northern Plateau,

Spain.Thestudywasperformedina120-year-oldeven-agedpure standin CorbejónyQuemadospublicforest(41◦28N,4◦43W). Site location was selected and regeneration felling treatments designedtorepresenttypicalconditionsinamaturemanaged for-est,whenrestrictionsonconecollectionforcommercialpurposes arecommonlyimposedtoallowforseedrainandregeneration. Regenerationfellingscommencedduring2002–2003followingthe highly intensive seed tree method(ST) and the more progres-siveshelterwoodmethod(SW).Bothsystemshavebeenbroadly applied as regeneration treatments for the species. Pre-felling and post-felling standdensities are shown in Table1. Climate iscontinental-Mediterranean.Meanmonthlytemperaturesrange from4.0◦C inJanuaryto21.7◦CinJuly.Meanannual precipita-tionis435mm,withaperiodofsummerdrought(July–September meanprecipitationof66mm).Siteindexis15–16mat100years, characteristicofaIIclassquality(Calamaetal.,2003).Thisindex definesthequalityofastandasafunctionofitsdominantheight ataparticularage.Theconsidereddominantheightcriterionwas theheightofthosetreeswhosediameteratbreastheight(1.3m; “dbh”)wasincludedamongthe20%ofthethickesttreesofthestand (Weise,1880).

Table1

Summaryofstanddensities.

Plot Treatment Nb/fc(ha−1) Nd(ha−1) BAe(m2/ha) Dgf(cm) Hg(m) FCCh(%)

1 STa 144 46 8.17 47.6 13.6 19

2 ST 115 48 9.37 49.9 15.5 22

3 ST 156 46 6.99 44.1 12.6 14

4 SWb 192 73 10.82 43.4 14.1 31

5 SW 233 75 9.70 40.6 12.9 30

6 SW 169 75 12.26 45.6 15.8 34

7 Control 149 149 18.42 40.1 13.8 70

aST—seedtreemethod. b SW—shelterwoodmethod.

c Nb/f—densitypriorfellings.Afterfellings. d N—remainingdensity.

eBA—basalarea.

f Dg—quadraticmeandiameter. gH—averageheight.

h FCC—forestcanopycover.

2.2. Experimentaldesign

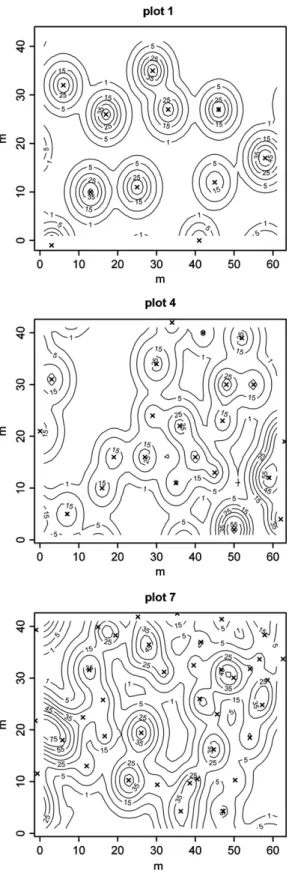

Theprimarydispersaltrialwasinstalledin2005,toallowfor astandresponsetofellingsinconeproduction.Itconsistedofsix 60m×80m(0.48ha)sampleplotsthatwereestablishedunder dif-ferentstanddensitiesproducedbyregenerationfellings.Densities inplots1–3wererepresentativeoftheSTmethod,whereasthose inplots4–6weredistinctiveoftheSWmethod.Ontheonehand, thesetreatmentsprovidedaconvenientrangeofstanddensities, essentialformodellingpurposes.Ontheotherhand,theyofferan excellentframeworkforfurthermodelsimulation.A7.5mbuffer areawasincludedaroundeachplot,increasingtheoverallplot sur-faceupto0.7ha.Anavailablecontrolplot(nofellings)ofidentical dimensionswasusedexclusivelyforsimulationpurposes.Graphic informationaboutplotscanbefoundinFig.A.1inAppendixA.

Alltreeswithinplotswerestemmappedandmeasured.Tree measurements included dbh, total height, and 4 perpendicular crownradiiincardinaldirections.

InMay2005,asystematicgrid(17.7m×17.7m)often circu-larseedtrapsof0.25m2 wasestablishedwithineach ofthesix plots(controlexcluded).Twotrapsinplot1weredestroyedatthe beginningoftheexperimentandwerediscardedfromthe analy-sis.Theshortestdistancefromatraptoplotboundarywas12m. Thetrapdesignwasabagmadeoftextilefinemeshstapledon threewoodensticksat1mabovetheground(topreventrodent predation).Trappedseedswerecollectedon60occasionsfromtrap deploymenttoJanuary2011atintervalsaveraging34.6days(range from19to70,standarderror1.26),withlongestintervals corre-spondingtolowintensityseedrainmonthsordifficultaccessto plots(winter).

2.3. Modellingthespatialpattern

2.3.1. Theinversemodellingapproach

In order to determine the spatial pattern of dispersal, an approach based on non-mechanistic models involving inverse modellingprocedureswasattempted(sensuRibbensetal.,1994). Withthistypeofmodel,theseedshadowiscalculatedasthe prod-uctoftwofactors:thekernelandsourcefertility.Thefirstfactor, thekernel(kij),representstheprobabilitythataseedisprimary dispersedtolocationi,givenasourcejandtravelling,isotropically, adistancerij(m).Thekernelimpliesparameterstobeestimated whichcontroltheshapeofthecurveasafunctionofdistance.The secondfactoris thefertilityofthesource.Inourapproach, the modeldevelopedbyCalamaetal.(2008)isusedtoestimateaverage coneweight(wcj)duringthestudiedperiod(2005–2010)foreach individualtreej.Ratherthanestimateaparametertoobtainthe numberofseedsfromtheresponsevariableoftheaforementioned

model,weusedthemodeldevelopedbyMorales(2009)topredict thenumberofseedsperkgofcones(P).Pwascalculated consider-ingaconstantfractionofconeweightattributabletoseeds(0.259) andassuminganaverageseedweightof0.615g.Consequently,the valueNij(seeds/m2)ofthegenericseedshadowforasingletreej atalocationiisdefinedas:

Nij=P·wcj·k(rij) (1)

Inthecaseofnon-discretesources(e.g.astand),thenumberof seedsreachingalocationiiscomputedasthesumoftheexpected numberofseedsdispersedtothislocationfromtheTtrees con-sidered.Inthatcase,thesummedseedshadowcanbeexpressed as:

Ni=P· T

j=1

wcj·k(rij) (2)

Notethatdefinitionofthesummedseedshadowleadsto indi-vidualtreekernelparameterization.

2.3.2. Sourcedetermination

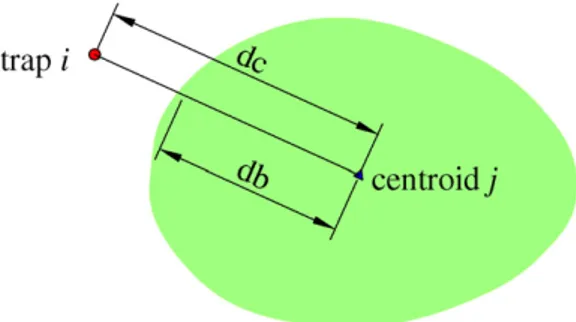

Formodellingpurposes,weoptimizedthenumberofsources T tocontribute tothesummedseed shadowata specific loca-tion.Therefore,weinitiallyplottedtheinversecumulativerateof seedarrivaltoeachtrapalongnormalizeddistances(totaldistance betweenatrapiandatreej(dc)/crownradiusdimension(db))to thenearesttree.Crownradiiwerecalculatedasthedistancefrom thecrowncentroidjtodriplineinthedirectionofthetrapi(Fig.1). Suchsimplificationindicatesboththedegreeofclumpingofdata andtherelativedistanceoftrapsnoreceivingseedstotheclosest tree.Thelatterdefinesthemaximumrelativedispersaldistance foundfromthedataavailable(2crownradii).Thus,theprocedure tooptimizetheTcontributorseedsourceswastoexcludefrom analysistreeslocatedoveradistanceof2crownradiifromtraps.

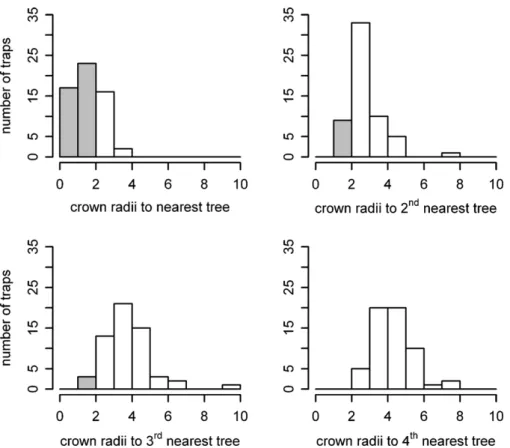

Fig.2.Histogramsoffrequencyforrelativedistancesfromtrapitotheclosest1st,2nd,3rdand4thtreej.Distancesbelow2crownradiiaregreycolouredforclarity.Note thatthe4thnearesttreewasalwaysfurtherthan2crownradii.Meancrownradiuswas3.5m.

Todoit,wecalculatedtheempiricaldistributionofdistancesin crownradiifromeachtraptothestemofthenearest1sttoTth tree.Then, Twasconsideredoptimumwhenthedistributionof distancesbetweentrapsandtheTth+1nearesttreeonlyincluded figuresover2crownradii,resultinginT=3(Fig.2).

2.3.3. Distancedefinition

Inordertoaccountforcrowneffectinthekernelvalue assign-ment, we computed standardized distances between traps and sources,normalizingthebeneath-crownsegmentdbtoan aver-agecrownradius(R),leavingtherest(beyondcrown)unaltered. Whenatrapwaslocatedbeneathacrownshadow,itsdistanceto sourcewasassessedasthecorrespondingproportionofR.Inturn, beneath-crowndistancesareslightlyrescaled,whereastwopoints locatedatthesamedistancetodriplineofequallyproductivetrees ofdifferentcrownsizesareconsideredtobereachedbythesame numberofseeds.Correcteddistancerij(m)analyticdefinitionis then:

(dc−db)+R¯ (dc/db)·R¯

ifthetrapisbeyondcrown

ifthetrapisbeneathcrown (3)

wheredbistherealcrownradiuslength;dcisthedistancebetween thecentroidoftreejandthetrapi.

2.3.4. Kernelformulation

Inordertoestimatetheseedshadowthatbestfitthedata,two kernelsweretested:theWeibull(Clarketal.,1998),andthe2Dt model(Clarketal.,1999b).Parameterestimationwasperformed throughthe optimizationof the log-likelihood functionfor the assumedtheoreticaldistributionofdata,throughavariantofthe simulatedannealingalgorithm(Belisle,1992).

TheWeibullkernelcanbere-formulatedas:

kij= 1 nexp

−

rij ˛

c(4)

where˛isthedispersalparameter,cistheshapeparameter,nis thenormalizer:

n=2··˛2·(2/c) c

with(·),thegammadistribution.

Shape parameter c is assessed together with ˛ in the log-likelihood maximization. Nevertheless, whenever optimization becomesunstableweassumed,likeClarketal.(1998),aGaussian curve(c=2).

Ontheotherhand,the2Dtkernelconsistsofareformulationof theWeibullcurvewithc=2,allowing˛tovaryalongrij:

kij= u

·p·(1+(r2ij/p))(u+1)

(5)

whereuisthescaleparameter,pistheshapeparameter.

2.3.5. Likelihoodfunctions

Parameters involvedin both kij formulations were achieved throughlog-likelihoodmaximizationofEq.(2),undertwo alter-nativehypotheses(Poissonandnegativebinomial)withrespectto thestochasticprocessofseedarrival.Inthecaseofthe2Dtmodel, onlythePoissonhypothesiswasused.Poissonandnegative bino-miallog-likelihoodsadaptedbyRibbensetal.(1994)andClarketal.

(1998),respectively,areexpressedas:

log=

i

log=

i

(log(yi+)−log(yi+1)−log()+yi·logNi

+·log−(yi−)·log(Ni+)) (7)

whereisthelikelihoodfunctiontomaximize,yiistheobserved numberofseedscollectedfromthetrapi,Niistheexpected num-berof seedsin trapi, is theclumping parameter,(·)is the gammadistribution.Maximizationofthelog-likelihoodfunctions wasassessedusingthedatafromalltrapssimultaneously.

2.3.6. Modelevaluation

Comparisons between models were performed through the AkaikeInformationCriterion(AIC)totestmodelaccuracyandselect thatonewhichbestfittedthedata.Wealsocomputeda regres-sionbetweenobservedandexpectedseeddensityvalues,testing whethertheinterceptandslopedifferedsignificantlyfrom0and1, respectively(H0:intercept=0,slope=1),asameasureofthelevelof concordancebetweendataandmodel.Inaddition,thecoefficient ofdeterminationforthisregressionwascalculated,assuggested byClarketal.(1998).

2.3.7. Seedlimitation

Forthetwoproposedregenerationfellingtreatmentsand con-trol,wetestedwhetherchangesindensity(post-harvestingbasal area)couldleadtoseverevariationsinseedavailability(inregard toboth abundance and occurrence).Thiswas accomplishedby computingthesourcelimitationindex,orSL,andthedispersal lim-itationindex,orDL(Clarketal.,1998;Muller-Landauetal.,2002). SLisexpressedastheproportionofsiteswherenoseedsarrive assumingthatthetotalamountofseedsisdistributeduniformly:

SL=1−Pr

ˆ

Ni>0|Poisson Nˆi

⁄

l=e− Nˆi

⁄

l(8)

with ˆNi,theexpectednumberofseedsreachingthelocationi,andl, thenumberoflocationstakenintoconsideration.DLcanbedefined asthecomparisonbetweentheproportionofsitesactuallyreached bydispersedseedsandtheproportionoflocationswhereseeds wouldarriveifdispersalwereuniform,whereaisthenumberof pointsreachedbyatleastoneseed:

DL=1−

a/l 1−SL

(9)

Usingthebestmodel,weassessedasimulatedseedrainat1m2 scalethroughout2501points(l)locatedin aregulargridinthe central41m×61mrectangleofeachplot.Regardingmodel con-sistence,distancesbetweensimulationpointsandtreesmustbe modifiedsimilarlytoEq.(2).ThesesimulationsallowedforSLand DLcalculationthroughoutallplots,includingthecontrol.

2.4. Modellingthetemporalpattern

Inordertomodelseeddispersalfromatemporalperspective, thetotalseedcollectedintrapsduringeachdatacollectioninterval wasgraphicallycomparedwiththatperiod’smeanclimate vari-ables,includingmeantemperature,maximumtemperature,mean relativehumidityandtotalprecipitation.Basedonthisanalysis,the mostsuitablevariableswereselectedtocontroltheprocessofcone opening.AllclimatedatawereachievedfromOlmedo meteorolog-icalstation(coordinates41◦1734N,4◦4058W).

Concerningseedrelease,weconstructedaresponsevariable(sr) relatedtothetotalamountofcollectedseedsthatalsoaccounted fortheseasonallydecreasingaerialseedbankovertime, asthe percentageofseedsreleasedin aparticularperiodwithrespect tothetotalamountofseedsremainingin thecone.Thenature oftheresponsevariable(apercentage)rendersit insensitiveto

extremelylowconecrops,thusweonlyconsideredyearsof appre-ciablecropsintheanalysis(i.e.2006–2007,2007–2008,2008–2009 and2010–2011).Significantdifferencesamongyieldswere deter-minedviathenon-parametricKruskal–Wallistestfornon-normal data(˛=0.05).

Agraphicalanalysiswasalsoundertakentoidentifyprior rela-tionships betweenclimatevariables and sras a basis tomodel srthrough asimplelinearregression.In ordertoprevent unre-alisticconfidenceintervalsfortheparameters,anauto-regressive errorstructurewasappliedwithindispersal periods,due tothe fact that theobservations oftheresponse variable are intrinsi-callyautocorrelatedfromatemporalperspective.Inaddition,those caseswheresr=100werenotusedintheregressionasitisa con-stantthroughoutallterminalvaluesofeverydispersalperiodwith no ecologicalmeaning. Eventually,potential transformations in explanatoryvariableswerecarriedoutwhennecessarytolinearize therelationship.Modelevaluationwasperformedcomparingthe AICofalternativemodels.

Allstatisticalanalysesandcalculationsinthisstudywere per-formedinR2.12.0(RDevelopmentCoreTeam,2009).

3. Results

3.1. Seedrain

During the dispersal periods from 2005to 2010, 753seeds werecollectedintheseedplots.Thespatialdistributionoftrapped seedswasnotuniform.24traps(41%)werenotreachedbyany seed during all periods. The Kruskal–Wallistest indicated sig-nificant differences among years in number of seedscollected (2=48.6924, p-value<0.0001). Dispersal was especially scarce (non-appreciable)during2005–2006(6seeds)and2009–2010(7 seeds);higheryieldsoccurredduring2008–2009(29seeds)and 2010–2011 (73seeds). In contrast, 2006–2007(237 seeds) and 2007–2008(401seeds)werestrongmastingyears.Statisticsper traparesummarizedinTable2.

ConeopeningtookplaceduringJuneandJulyallyears,when seedsreachingtrapsincreasedconsiderably.Concerningthe pro-gressiveseed releaseafteropening,although a strongdispersal peakoccurredatthebeginningofeachdispersalperiod,arelative maximumatadvancedstagesoftheprocessaroseasacommon featurefor allyears holdingappreciableyields(Fig.3).Notably, in2006alargeportionoftheyear’sdispersedseedsfellduring November.Thesametrendoccurredin2007,whenahigh percent-ageoftheyear’sseedfallwascollectedduringSeptember.In2008, thepeakoccurredinOctober,whilein2010twolatemaximawere recordedinSeptemberandNovember.Duringtheyearsof appre-ciableconecrop,thosedatacollectionintervalsoflesserseedrain intensityshowedaresidual(non-null)dispersalrate,withonlyfour lagswherenotrappedseedswerefound.

3.2. Spatialpattern

TheWeibullmodelconsideringaPoissondistributionofdata (henceforthW.P)provedthemostaccurate,withthelowestAIC value,togetherwiththe2Dtmodel(Table3).Themaximizationof thenegativebinomiallog-likelihoodfunctionfortheWeibullcurve (hereafterW.NB)presentedhighinstabilityinparameter estima-tionevenfixingc.Theclumpingparameterinthenegativebinomial hadatrendtolargevalues(>100),meaninglackofoverdispersion inthedata.

Table2

Mainannualseeddispersalstatisticspertrapandseedraindensity(seeds/ha).

Period 2005–2006 2006–2007 2007–2008 2008–2009 2009–2010 2010–2011

Mean 0.10 4.09 6.91 0.50 0.12 1.26

SDa 0.36 9.24 11.65 1.23 0.46 2.57

CIb(95%) ±0.09 ±2.38 ±3.00 ±0.32 ±0.12 ±0.66

Seeds/ha 4137.93 163448.28 276551.72 20000.00 4827.59 50344.83

aSD:standarddeviation. bCI:confidentintervals.

Fig.3.Numberofseedstrapped(solidline),monthlymeanrelativehumidity(dottedline)andmonthlymeantemperature(dashedline)during2005–2010.

Table3

Estimatedparameters,AICandlog-likelihood(log)forthefittedmodels.Inbolds,thelowestAIC.Coefficientofdetermination(r2)amongobservedandpredictedvalues foreachmodelisalsoshown.

˛ c u p AIC r2 log

W.P 3.308 2.065 – – 2358.300 0.428 −1177.150

2Dt – 2a 24.837 253.6 2358.758 0.424 −1117.379

aFixedparameter.

proposedapproaches.Basically,themodelsdifferedinseed disper-salestimationatshortdistances(beneathcrown)withexpected densityatsourcerangingfrom39.89(2Dt)to37.71seeds/m2(W.P), asillustratedinFig.4foranaveragetreewitha3.5mcrownradius. Theprobabilitythataseedisdispersedbeyondcrownvariedfrom 0.312(W.P)to0.310(2Dt).Beyond3.5mfromthedripline(2mean crownradii),theprobabilitywaslessthan0.01forallmodels, indi-catingahighlyaggregatedspatialpattern(Fig.5).

Ahighlevelofagreementbetweenmodelanddatawasfoundin thecaseoftheW.Pmodel.AsshowninFig.6andTable3,therewere

Fig.4. Comparisonofseeddensitycurvesproducedbythefittedmodelsforan averagetreewithcrownradiusR.

noevidencesforrejectingthenullhypothesisofalinear relation-shipwithslope=1(p-value>0.05)andintercept=0(p-value=0.24) amongobservedandexpectedvalues.Coefficientsofdetermination betweenthemintheW.Pand2Dtmodelsweresimilar(Table3), exhibitingrelativelylowvalues.

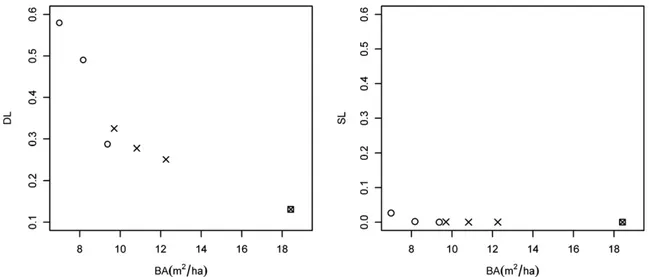

Simulations to calculate limitation indexes were performed withtheW.Pmodel(Fig.4).Sourcelimitationindex(Fig.7) indi-catedthatlimitationduetoseedavailabilitywasnegligibleforall plots(SL<0.005),implyingthatunderauniformseedrain,mostof thespacewould bereached. Dispersallimitationshoweda ten-dency for lower values as basal area increased(Fig.6). Atlow densities(basalarea<9m2/ha;plots3and1),DLwas0.58and0.49, respectively;itwas0.32(plot5),0.29(plot2),0.28(plot4)and0.25 (plot6),wherebasalareawasbetween9and13m2/ha.DLinthe controlplotwas0.13(basalarea=18.4m2/ha).

3.3. Temporalpattern

Anexploratoryanalysisofdifferentclimatevariablesshowed thatconeopenedwhenmeantemperatureofdatacollection inter-vals(mostlymonthly)reached19–20◦C(Fig.3).However,when consideringthesubsequentseedrelease,therewasnoapparent relationshipofthenumberofharvestedseedstotemperature vari-ablesormeanrelativehumidity.

Onthecontrary,whentakingintoaccountthepercentageof seeds fallen during the collecting interval related to the over-all amountof seeds tobe released at theend of thedispersal period(sr),asynchronicpatternwithtotalprecipitationwasfound (Fig.8;anomalousvaluesinthistrendwerethosecorresponding toFebruaryandMarchof2007).

Fig.5.Examplesofseedshadowmapsforplot1(STtreatment),plot4(SW treat-ment)andplot7(control).Crossescorrespondtostemslocations.Linesrepresent levelsofequalpredictedseeddensity(valueindicatedbythefigurewithinlines).

as the explanatory variable (see Table 4, Fig. 9). A slight improvementintheAICvaluewasobtainedwhenan autoregres-sivestructure (AR-1) wasapplied withineach dispersal period (rangingfrom285.939withoutstructure to284.538with struc-ture).

Fig.6.Observedvsexpectedseedshadowintrapsi.Solidlineindicatesatheoretical perfectagreementbetweenmodelanddata(slope=1,intercept=0).Dottedline showstherealdegreeofaccordance(slope=0.858;intercept=2.361).

4. Discussion

4.1. Theinversemodellingapproach

We attempted to fit empirical models using inverse mod-elling procedures todescribe and predictseed shadowand, by implication,thespatialpatternofprimaryseeddispersalandits consequencesinnaturalregenerationinP.pinea.Ourmain con-cern wasshortdispersaldistance,particularly,thescopeofthe crown.Therefore, weusedtwocompetingmodels(Weibulland 2Dt) that workproperly atthis scale. Eventhoughthe flexibil-ityofthe2Dtkernelwasdevelopedtoaccountforlongdistance events (Clark et al., 1999b), those models have been reported to underestimatelongdispersal distances (Debain etal., 2007), incomparisonwiththemixturemodelproposedbyBullockand

Clarke(2000).Similarly,mechanisticapproacheswerenottaken

into consideration,as theyhavebeen developedusing physical variables specificallyrelatedtowinddispersalmechanisms(e.g.

GreeneandJohnson,1989;BullockandClarke,2000;Stoyanand

Wagner,2001;butseealsoMartínezandGonzález-Taboada,2009)

oreven tomodelsecondarydispersal byanimals(Greeneetal., 2004).

Aseriousconstraintofinversemodellingisthatplotsizeand spatialdistributionofseedtrapsmayleadtounderestimationof mean dispersal distancewhen leptokurtic dispersal takes place (Robledo-ArnuncioandGarcía,2007).However,thisproblemdoes notseverelyapplytothisstudy,asanextremelyhighkurtosisisnot expectedinP.pinea,providedgravityprimarydispersalstrategyin thespecies.Inaddition,ourregulargridmaximizesthenumber oftrapsbetweenoneandtwocrownradii,wheredroppedseeds intrapscommencetobeuncommon(deficientsamplinginthose circumstancescouldresultinanunreliableparameterestimation). Anindirectconsequenceofdispersalfeatureisthatthearrivalof

Table4

Summaryoftheestimatedcoefficientsforthefittedmodelbetweenvariablesrand thecubicrootofpp(precipitation).ϕistheauto-regressiveparameteroforder1 indicatingcorrelationbetween2consecutiveobservations.

Coefficient Standarderror t p-value

Intercept −0.0989 9.2157 −0.0107 0.9915

3

√

pp 10.1624 2.7346 3.7162 0.0008

Fig.7. Sourcelimitation(SL)anddispersallimitation(DL)indexesvsBA(m2/ha)forthesevenplots.Circlesindicateseedtreetreatment;crosses,shelterwoodtreatment;

andthesquaredsymbolcorrespondstothecontrol.

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

Jun-0 5 Sep-0

5 Dec-0

5 Mar-0

6 Jun-0

6 Sep-0

6 Dec-0

6 Mar-0

7 Jun-07Sep-0

7 Dec-0

7 Mar-0

8 Jun-0

8 Sep-0

8 Dec-0

8 Mar-0

9 Jun-09Sep-0

9 Dec-0

9 Mar-1

0 Jun-1

0 Sep-1

0 Dec-1

0

sr (%)

0 50 100 150 200 250

pp (mm)

Fig.8.Variablesr(solidline)andtotalprecipitationperdispersalperiod(dashedline)intime.Forclarity,wedonotshowsrdatafrom2005to2006and2009to2010 dispersalperiods(negligible).Notethatsr=100correspondstothelastvalueofeachdispersalperiod.

immigrantseedsisexpectedtobeahighlyunlikelyeventinthis case,consideringalsothespatialdispositionofthegridinregard totheplotboundaries.

Ontheotherhand,althoughgeneticanalysisdealswiththese difficulties,dispersalkernelestimationthroughparentage analy-sisrequirestheuseofhighlyvariablemolecularmarkers,which

Fig.9.Regressionmodelforthetemporalpatternofseedrelease (solidline) betweensrandthecubicrootoftotalprecipitation(pp).Datafromthedispersal yearsusedtofitthemodelaredisplayedseparately.

provide an exact identification of all potential seed sources

(Robledo-Arnuncio and García, 2007; Jones and Muller-Landau,

2008).Thisinterestingandpowerfultechniqueisunfeasibletobe

appliedinthecaseofP.pinea,duetotheextremelylowgenetic diversityinthespecies(Vendraminetal.,2008).

Dependingonthenatureofthedata,severalauthorshave pro-poseddifferenttheoreticaldistributionstofitthedispersalmodels. TheobviousapproachisthePoissondistribution,astheresponse variableisobtainedfromcounts(Ribbensetal.,1994;Sagnardetal.,

2007).However,Clarketal.(1998)firstappreciatedthe

unsuit-abilityofthePoissonprocesswhenclumpingofdatawaspresent, suggestingtheuseofthenegativebinomialdistributioninstead. Thisinterestingfindingandthesubsequentproposalmaydealwith clumping,atcostofanextraparameter(),being,inpractice,a generalizationofthePoissonapproach.Indeed,tendstobelarge whendataaccommodatesaPoissonprocess.

The2DtmodelinvolvesthePoissonassumptionbydefinition. Thisvery flexible Gaussianmodeldealsreasonably wellwitha clumpeddatadistribution,notbeingessentialtoconstructcomplex likelihoodfunctions(Clarketal.,1999b).However,weattempted thenegativebinomialfortheWeibullmodel.Parameterestimation became unstable and the clumping parameter frequently pro-duced high figures (>100; in contrast to Clark et al. (1998)). Consequently,weusedthePoissonlikelihoodasaparticularcase ofthenegativebinomialtoachieveaccurateestimates. Difficul-tiesinfittingandlackofstabilityarenotuncommonforpoorly primarydispersedspecies(zoochorousandbarochorusdispersal syndromes)asreportedbyClarketal.(1998)andMartínezand

Eventually,giventhespecificfeaturesofP.pineaspatialprimary dispersal,allmodelsshowedasimilarbehaviorintermsof predic-tion(comparabler2),withslightdifferencesnearbythestem.In addition,thecoefficientofdeterminationwasrelativelylow,asa resultofincreasingvariancewithmeanvalues(Poisson assump-tion),especiallyatshortdistances(belowcrown).

4.2. Modelimprovements

InaccordancewiththefindingsofRodrigoetal.(2007),through ourpreliminaryanalysistoestimatethemaximumrelative disper-saldistance(crownradii),itwasobservedthatseedtrapslocated furtherthantwocrownradiifromthenearesttreeseldomreceived anyseed,dropping 80%ofseedsunderthecrown.This circum-stance,duetotheaforementionedgravitydispersalpatternandto thelowstanddensities,allowedustoassumealimitednumber ofsources associatedwitheach trap.Consequently, itwas pos-sibletoimprovecomputing efficiencytoassess highresolution distancesand,inturn,tosupplymoreaccurateinputsformodel fit.Inaddition,oursystematictrapdesign,deployedthroughouta varietyofstanddensities,providedahighrangeofdistancesunder thisassumption,whichconstitutesadesirablecircumstance(Clark etal.,1998).

Commonly,inversemodellingproceduresreduceseedsources to points. To our knowledge, there is no study where crown sizehasbeentakenintoaccountinkernelparameterization,but

Sagnardetal.(2007)inadifferentcasestudy.Nevertheless,due

totheumbrella-likeshapeofP.pineacrownsandconeoccurrence throughouttheupperfractionofthecrown(Mutkeetal.,2005b), thewholecrownmust beconsideredasa seedsource.Besides, asitssizemaystronglyinfluenceprimaryseedarrival(Barbeito etal.,2008),itisofgreatinteresttopredicttheproportionofseeds droppedbeneathcrowns.Weproposeamethodthatsuccessfully accomplishesthisobjective.Providingthatasummedseedshadow modelimpedesusingrelativedistances(crownradii)betweentrees andtraps,duetodimensionalinconsistence,distancesfromtrap tosourcearecorrected,implyingadoublescale:beyondcrown, distancetothedriplineisknownandunaltered,whereasbeneath crown, relative distances are assessed in terms of crown radii (1crownradius=3.5m,meancrownradiusatourexperimental plots).BeyonditsapplicationinP.pineastands,theapproach pro-videsaninterestingtooltoaccuratelystudyprimarydispersalin large-seededspecieswithbroadcrowns(e.g.genusQuercus),with modestchangestocustomizethemodel(meancrownradius).

Oneofthemaindrawbacksinclassicseedshadowestimation usinginversemodellingisthatitrequiressourcefecundityfigures. Frequently,thesevaluesaredifficulttoachieveandaredefinedas theproductofsomeknownvariablerelatedtoseedproductivity. Forexample,dbh(Ribbensetal.,1994;Clarketal.,1998;Uriarte

etal.,2005)ornumberofcones(Sagnardetal.,2007)plusa

param-etertoestimatenumberofseedsperdbhunitorcone.Adifferent approachwasproposedbyNanosetal.(2010),wherefecunditywas allowtovaryamongtreeswithoutrestrictions.Thesimultaneous estimationoffecundity anddispersalparameters maycomprise highinstabilityintheprocess(Clarketal.,2004;Nanosetal.,2010). Inourapproach,wereducedmodelcomplexityderivedfromthis issuebyestimatingfecundityviatheexistingmodeldevelopedby

Calamaetal.(2008)andthedimensionalcorrectionsassessedby

Morales(2009),whichenableaccuratepredictionofseed

produc-tioninP.pineaasafunctionofdbhandsiteindex.

4.3. Spatialpatternofseeddispersal

The seed shadow estimated from the selected model (W.P) showedahighlyaggregatedspatialpatternofprimaryseed dis-persalfor P.pinea. Therefore,the presenceof dropped seedsis

boundedbeneathcrownsorinnearbyareas(uptotwocrownradii foranaveragetree),infullaccordancewiththefindingsofRodrigo

etal.(2007).Simulationsproducedbytheselectedmodelallowed

toattainsourceanddispersallimitationindexes.Comparisonsof theseindexeswiththecorrespondingbasalareavalueswithineach plotshowedthatsourcelimitationwasnegligibleforallplots con-sidering thewholeperiod,althoughdue tothespecies’masting habit,limitationwouldoccurfrequentlyinnomastyears(Calama

etal.,Unpublisheddata).Nevertheless,theresultssupportedour

hypothesis thatcurrent managementdensitiesare inefficientin regardtodispersallimitation.Forpost-harvestbasalareavalues underbothregenerationfellings(especiallytheseedtreemethod), thecurrentseedshadowsproducedanotablepercentageofgaps wheredispersedseedsarenotexpectedtoarrive.Theseresultsare consistentwiththose fromDallingetal.(2002)when consider-inglarge-seeded,non-zoochorusspecieswithlowdensitieswithin astand.Thisissuecouldlimitnaturalregenerationifstand den-sityisreducedpriortoseedlingestablishment,particularlywhen basalareaisreducedbelowacriticalvalueof10m2/ha(seedtree method).Inthatcircumstance,theremainingtreesareinsufficient tosuccessfullyregeneratethestand,evenifhighlyfavorable disper-saleventstakeplace,andthusnecessitatingartificialregeneration (directseeding).Thisscenarioconstitutesacommoncircumstance givencurrentfellingschedules,involvingdensitiesthatrangefrom 50 to75stems/haduring thefirst 10 years oftheregeneration period(Monteroetal.,2008).

4.4. Temporalpatternofseeddispersal

From a temporal perspective, the results also support our hypothesisthatclimatecontrolsconeopeningandseedreleaseinP.

pinea.Duringourstudy,conesopenedinresponsetoatemperature

threshold(19–20◦C).Accordingly,Tapiasetal.(2001),ina compar-ativestudyundercontrolledconditions,foundthatP.pineacones openingtookplaceasapunctualprocessat28◦C(thelowest tem-peraturetested).Ontheotherhand,therelationshipbetweensrand totalprecipitationcouldbeconnectedtopassivephysicalprocesses involvingscaletissuesstructureandchangesinrelativehumidity (Dawsonetal.,1997).Thatwouldpromoteconescalesmovements, alternativelyopeningand closing thecone,which would facili-tate seed release.Contrastingly, Masettiand Mencussini (1991) observeddispersalpeaksforP.pineaduringthedriestmonthin twocorrelativeyearsinToscana(Italy),althoughthatanalysiswas performedwithouttakingintoaccounttheseasonallydecliningof thecanopyseedbank.In ourcase, suchaneffectwasobserved onlyduringthedispersalpeakthatbeganinMarch2007.Adaily analysisofprecipitationratesshowsthatmostoftherainfalltook placeattheendofthepreviousinterval(February)along correl-ativedays.However,thedispersalpeakwasrecordednextmonth (March,whichwasdrier).Thisdiscrepancymightindicatethatseed releasecanbecontrolledbyalternatedryandhumideventsin cli-matescharacterizedbyalowerandmoreunevenprecipitationthan inToscana,suchastheSpanishNorthernPlateau.Similarly,Nathan

etal.(1999)claimedthatPinushalepensisseedreleasewasstrongly

relatedtoextremelydryandhotclimateevents.Althoughrainfall wasnotinvolvedintheprocess,shortchangesinhumiditywith respecttopriordailyvaluesproducedtherelease.

4.5. Managementimplications

OurfindingssuggestthatunderthecurrentmanagementofP.

pineastandsintheNorthernPlateau,primarydispersalcould

outpoorphysiologicalperformance ofseedlingslocatedbeyond thecrown influence,whereas Calama et al.(Unpublished data) observedhighermortalityinseedlingslocatedbeyondtwocrown radiifromtrees.Inaddition,Awadaetal.(2003)establishedthat

P.pinearesponsetolateshadereleasingdidnotconditionfurther

plantdevelopment.Therefore,theabsenceoflongdispersal dis-tanceeventscouldapparentlybeneficiatethespecies.Themodels developedinthisstudyshowedahighlyclumpeddispersal spa-tialpattern,wheretheoccurrenceofseedrainisintimatelyrelated torainfallevents.Seedlimitationindexesobtainedfromselected modelsimulationssuggestthatnaturalregenerationfailureisdue to,atleastinpart,dispersallimitation.Inaddition,asseedrelease provedclimate-controlled,currentfellingschedulesfollowingno ecologicalcriteriacanresultinunsuitabledensityreductionbefore dispersaltakesplace.Thesespatialandtemporalconstrictionslimit dispersalthroughspaceandtime,andindicatethatpresent silvicul-turepracticesinP.pineastandscanbemodifiedinordertooptimize seedarrival.Areductionintheintensityofregenerationfellings andtheirschedulingafewyearsaftertheoccurrenceoffavorable recruitmenteventswouldreducetheprobabilityofregeneration failurethroughamoreevenlydistributeddispersal.Becausethe controldispersal limitationindexshowedanegligibleseed lim-itationwithrespect tobasal area, theresidual densities atthe beginningoftheregenerationperiodshouldexceed16–18m2/haof basalarea.Regenerationfellingsshouldbelimitedtopost-dispersal periods,aftertherainfallsthatfollowcone openinginthis area (i.e.October–December)inordertoguaranteethereleaseofallthe seeds.Inconclusion,silviculturalrecommendationsbasedonthe modelsdevelopedinthepresentstudywouldincreasethe avail-ableseedinthesoilbanknecessaryforthenextprocessesinnatural regeneration.

Acknowledgements

WearegratefultotheForestServiceoftheJuntadeCastillay LeónandinparticulartoAyuntamientodeElPortilloforpermission toconductthefieldexperiment.WealsowishtothankGuillermo Madrigal and Enrique Garriga for their help in data collection. Finally,wewouldliketoexpressourgratitudetoDavidAffleckfor hissuggestionsonRprogrammingandJuanJoséRobledo-Arnuncio for hishelpful comments that improved notably the text.This researchwassupportedbyINIAprojectRTA2007-00044.

AppendixA. Supplementarydata

Supplementarydataassociatedwiththisarticlecanbefound,in theonlineversion,atdoi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2011.11.028.

References

Awada,T.,Radoglou,K.,Fotelli,M.N.,Constantinidou,H.I.A.,2003.Ecophysiologyof seedlingsofthreeMediterraneanpinespeciesincontrastinglightregimes.Tree Physiol.23,33–41.

Barbeito,I.,Pardos,M.,Calama,R.,Ca ˜nellas,I.,2008.Effectofstandstructureon stonepine(PinuspineaL.)regenerationdynamics.Forestry81,617–629. Belisle,C.J.P.,1992.Convergencetheoremsforaclassofsimulatedannealing

algo-rithmsonR(d).J.Appl.Prob.29,885–895.

Bullock,J.M.,Clarke,R.T.,2000.Longdistanceseeddispersalbywind:measuring andmodellingthetailofthecurve.Oecologia124,506–521.

Calama,R.,Canadas,N.,Montero,G.,2003.Inter-regionalvariabilityinsiteindex modelsforeven-agedstandsofstonepine(PinuspineaL.)inSpain.Ann.Forest Sci.60,259–269.

Calama,R.,Gordo,F.J.,Mutke,S.,Montero,G.,2008.Anempiricalecological-type modelforpredictingstonepine(PinuspineaL.)coneproductionintheNorthern Plateau(Spain).For.Ecol.Manage.255,660–673.

Calama,R.,Manso,R.,Barbeito,I.,Madrigal,G.,Garriga,E.,Gordo,F.J.,Montero,G., Ca ˜nellas,I.,Pardos,M.,Unpublisheddata.Doesinter-specificdifferencesinseed sizedeterminenaturalregenerationtraitsinPinuspineaandPinussylvestris? Calama,R.,Montero,G.,2007.Coneandseedproductionfromstonepine(Pinuspinea

L.)standsinCentralRange(Spain).Eur.J.ForestRes.126,23–35.

Calama,R.,Mutke,S.,Tomé,J.,Gordo,J.,Montero,G.,Tomé,M.,2011.Modelling spatialandtemporalvariabilityinazero-inflatedvariable:thecaseofstone pine(PinuspineaL.)coneproduction.Ecol.Model.222,606–618.

Clark,J.S.,Beckage,B.,Camill,P.,Cleveland,B.,HilleRisLambers,J.,Lichter,J., McLach-lan,J.,Mohan,J.,Wyckoff,P.,1999a.Interpretingrecruitmentlimitationin forests.Am.J.Bot.86,1–16.

Clark,J.S.,LaDeau,S.,Ibanez,I.,2004.Fecundityoftreesandthe colonization-competitionhypothesis.Ecol.Monogr.74,415–442.

Clark,J.S.,Macklin,E.,Wood,L.,1998.Stagesandspatialscalesofrecruitment limi-tationinsouthernAppalachianforests.Ecol.Monogr.68,213–235.

Clark,J.S.,Silman,M.,Kern,R.,Macklin,E.,HilleRisLambers,J.,1999b.Seed disper-salnearandfar:patternsacrosstemperateandtropicalforests.Ecology80, 1475–1494.

Dalling,J.W.,Muller-Landau,H.C.,Wright,S.J.,Hubbell,S.P.,2002.Roleofdispersal intherecruitmentlimitationofneotropicalpioneerspecies.J.Ecol.,90. Dawson,J.,Vincent,J.F.V.,Rocca,A.M.,1997.Howpineconesopen.Nature390,

668.

Debain,S.,Chadoeuf,J.,Curt,T.,Kunstler,G.,Lepart,J.,2007.Comparingeffective dispersalinexpandingpopulationofPinussylvestrisandPinusnigraincalcareous grassland.Can.J.For.Res.37,705–718.

Ganatsas,P.,Thanasis,G.,2010.PinushalepensisinvasioninPinuspineahabitatin Strofyliaforest(SiteofNATURA2000network),southernGreece.J.Nat.Conserv. 18,106–117.

Gómez-Aparicio,L.,Gómez,J.M., Zamora,R.,2007. Spatiotemporalpatterns of seeddispersal inawind-dispersedMediterranean tree(Aceropalussubsp granatense):implicationsforregeneration.Ecography30,13–22.

González-Martínez,S.C.,Burczyk,J.,Nathan,R.,Nanos,N.,Gil,L.,Alía,R.,2006. Effec-tivegenedispersalandfemalereproductivesuccessinMediterraneanmaritime pine(PinuspinasterAiton).Mol.Ecol.15,4577–4588.

Greene,D.F.,Canham,C.D.,Coates,K.D.,Lepage,P.T.,2004.Anevaluationof alterna-tivedispersalfunctionsfortrees.J.Ecol.92,758–766.

Greene,D.F.,Johnson,E.A.,1989.Amodelofwinddispersalofwingedorplumed seeds.Ecology70,339–347.

Jones,F.A.,Muller-Landau,H.C.,2008.Measuringlong-distanceseeddispersalin complexnaturalenvironments:anevaluationandintegrationofclassicaland geneticmethods.J.Ecol.96,642–652.

Levin,S.A.,Muller-Landau,H.C.,Nathan,R.,Chave,J.,2003.Theecologyand evolu-tionofseeddispersal:atheoreticalperspective.Annu.Rev.Ecol.Evol.Syst.34, 575–604.

Magini,E.,1955.Sullecondizionidigerminazionedelpinod’Aleppoedelpino domestico.ItaliaForestaleeMontana,AnnoX:,106–124.

Manso,R.,Calama,R.,Madrigal,G.,Garriga,E.,DeBlas,S.,Gordo,F.J.,Pardos,M. Dis-persiónprimaria,dispersiónsecundariaypredaciónpost-dispersiónenPinus pineaL.In:J.Gordo,R.Calama,M.Pardos,F.BravoandG.Montero(Eds.),La regeneraciónnaturaldePinuspineaL.yPinuspinasterAit.enlosarenalesde laMesetaCastellana.ActasdelasIJornadasdeTransferenciaTecnológicay Científica,inpress.

Manso,R.,Pardos,M.,Garriga,E.,DeBlas,S.,Madrigal,G.,Calama,R.,2010.Modelling thespatial–temporalpatternofpost-dispersalseedpredationinstonepine (PinuspineaL.)standsintheNorthernPlateau(Spain).In:FrugivoresandSeed Dispersal:MechanismsandConsequencesofaKeyInteractionforBiodiversity, Montpellier,France.

Martínez,I.,González-Taboada,F.,2009.Seeddispersalpatternsinatemperate for-estduringamastevent:performanceofalternativedispersalkernels.Oecologia 159,389–400.

Masetti,C.,Mencussini,M.,1991.Régénérationnaturelledupinpignon(Pinuspinea L.)danslaPinetaGranducalediAlberese(ParcoNaturalledellaMaremma, Toscana,Italie).Ecol.Mediterr.17,103–188.

Montero,G.,Calama,R.,RuizPeinado,R.,2008.SelviculturadePinuspineaL.In: Montero,G.,Serrada,R.,Reque,J.(Eds.),CompendiodeSelviculturadeEspecies. INIA—FundaciónCondedelValledeSalazar,Madrid,pp.431–470.

Morales,L.,2009.Modelosparalaprediccióndelcontenidoycalidaddepi ˜nónen pi ˜nasdePinuspineaL.enlosvallesdelTiétarydelAlberche.MasterThesis, UniversidadPolitécnicadeMadrid,Madrid.

Muller-Landau,H.C.,Wright,S.J.,Calderon,O.,Condit,R.,Hubbell,S.P.,2008. Inter-specificvariationinprimaryseeddispersalinatropicalforest.J.Ecol.96, 653–667.

Muller-Landau,H.C.,Wright,S.J.,Calderón,O.,Hubbell,S.P.,Foster,R.B.,2002. Assess-ingrecruitmentlimitation:concepts,methodsandcase-studiesfromatropical forest.In:Levey,D.J.,Silva,W.R.,Galetti,M.(Eds.),SeedDispersaland Fru-givory:Ecology,EvolutionandConservation.CABInternational,Wallingford, pp.35–53.

Mutke,S.,Gordo,J.,Gil,L.,2005a.VariabilityofMediterraneanstonepinecone pro-duction:yieldlossasresponsetoclimatechange.Agric.ForestMetereol.132, 263–272.

Mutke,S.,Sievanen,R.,Nikinmaa,E.,Perttunen,J.,Gil,L.,2005b.Crownarchitecture ofgraftedstonepine(PinuspineaL.):shootgrowthandbuddifferentiation.Trees 19,15–25.

Nanos,N.,Larson,K.,Milleron,M.,Sjostedt-deLuna,S.,2010.Inversemodelingfor effectivedispersal:doweneedtreesizetoestimatefecundity?Ecol.Model.221, 2415–2424.

Nathan,R.,Katul,G.G.,Horn,H.S.,Thomas,S.M.,Oren,R.,Avissar,R.,Pacala,S.W., Levin,S.A.,2002.Mechanismsoflong-distancedispersalofseedsbywind. Nature418,409–413.

Nathan,R.,Safriel,U.N.,Noy-Meir,I.,Schiller,G.,1999.Seedreleasewithoutfire inPinushalepensis,aMediterraneanserotinouswind-dispersedtree.J.Ecol.87, 659–669.

Nathan,R.,Safriel,U.N.,Noy-Meir,I.,Schiller,G.,2000.Spatiotemporalvariationin seeddispersalandrecruitmentnearandfarfromPinushalepensistrees.Ecology 81,2156–2169.

Ordó ˜nez,J.L.,Molowny-Horas,R.,Retana,J.,2006.AmodeloftherecruitmentofPinus nigrafromunburnededgesafterlargewildfires.Ecol.Model.197,405–417. Pardos,M.,Puertolas,J.,Madrigal,G.,Garriga,E.,deBlas,S.,alama,R.,2010.

Sea-sonalchangesinthephysiologicalactivityofregenerationunderanaturallight gradientinaPinuspinearegularstand.ForestSyst.19,367–380.

Prada,M.A.,Gordo,J.,DeMiguel,J.,Mutke,S.,Catalán,G.,Iglesias,S.,Gil,L.,1997. LasregionesdeprocedenciadePinuspineaL.enEspa ˜na.MinisteriodeMedio Ambiente,Madrid.

Ribbens, E., Silander, J.A., Pacala, S.W., 1994. Seedling recruitment in forests—calibratingmodels topredictpatterns oftree seedlingdispersion. Ecology75,1794–1806.

Robledo-Arnuncio,J.J.,García,C.,2007.Estimationoftheseeddispersalkernelfrom exactidentificationofsourceplants.Mol.Ecol.16,5098–5109.

Rodrigo,A.,Quintana,V.,Retana,J.,2007.FirereducesPinuspineadistributioninthe northeasternIberianPeninsula.Ecoscience14,23–30.

Sagnard,F.,Pichot,C.,Dreyfus,P.,Jordano,P.,Fady,B.,2007.Modellingseeddispersal topredictseedlingrecruitment:recolonizationdynamicsinaplantationforest. Ecol.Model.203,464–474.

Santos,B.A.,Melo,F.P.L.,Tabarelli,M.,2006.Seedshadow,seedlingrecruitment,and spatialdistributionofBuchenaviacapitata(Combretaceae)inafragmentofthe BrazilianAtlanticForest.Braz.J.Biol.66,883–890.

Schütz,J.P.,2002.Silviculturaltoolstodevelopirregularanddiverseforest struc-tures.Forestry45,329–337.

Stoyan,D.,Wagner,S.,2001.Estimatingthefruitdispersionofanemochorousforest trees.Ecol.Model.145,35–47.

Tapias,R.,Gil, L.,Fuentes-Utrilla,P.,Pardos, J.A.,2001.Canopy seedbanksin Mediterranean pines of southeasternSpain: a comparison betweenPinus halepensis Mill., P.pinaster Ait., P.nigra Arn. and P. pinea L. J. Ecol. 89, 629–638.

RDevelopmentCoreTeam,2009.R:ALanguageandEnvironmentforStatistical Computing.RFoundationforStatisticalComputing,Vienna,Austria. Tsakaldimi,M.N.,Tsitsoni,T.K.,Zagas,T.,Ganatsas,P.P.,2004.Aleppopine(Pinus

halepensis)naturalregeneration,withoutfire,intheKassandraPeninsula, north-ernGreece.In:Papanastasis,A.(Ed.),MEDECOSConference.25thApril–1stMay. Millpress,Rhodes,Greece.

Uriarte, M., Canham, C.D., Thompson, J., Zimmerman, J.K.,Brokaw, N., 2005. Seedlingrecruitmentinahurricane-driventropicalforest:lightlimitation, density-dependenceandthespatialdistributionofparenttrees.J.Ecol.93, 291–304.

Vendramin,G.G.,Fady,B.,Gonzalez-Martinez,S.C.,Hu,F.S.,Scotti,I.,Sebastiani,F., Soto,A.,Petit,R.J.,2008.Geneticallydepauperatebutwidespread:thecaseofan emblematicmediterraneanpine.Evolution62,680–688.

Weise,W.,1880.ErtragstafelnfürKiefer.J.Springer.