www.elsevier.es/rmuanl

REVIEW

ARTICLE

History

and

progress

of

antiviral

drugs:

From

acyclovir

to

direct-acting

antiviral

agents

(DAAs)

for

Hepatitis

C

O.L.

Bryan-Marrugo

a,

J.

Ramos-Jiménez

b,

H.

Barrera-Salda˜

na

a,

A.

Rojas-Martínez

a,

R.

Vidaltamayo

c,

A.M.

Rivas-Estilla

a,∗aDepartmentofBiochemistryandMolecularMedicine,SchoolofMedicine,‘‘Dr.JoséEleuterioGonzález’’,UniversityHospital,

UniversidadAutónomadeNuevoLeón,Monterrey,N.L.,Mexico

bDepartmentofInternalMedicine,SchoolofMedicine,‘‘Dr.JoséEleuterioGonzález’’,UniversityHospital,Universidad

AutónomadeNuevoLeón,Monterrey,N.L.,Mexico cUniversidaddeMonterrey,Monterrey,N.L.,Mexico

Received17December2014;accepted12May2015 Availableonline3July2015

KEYWORDS

HepatitisCvirus; Antiviraldrugs; Direct-acting antiviralagents (DAAs)

Abstract Thedevelopmentofantiviraldrugsisaverycomplexprocess.Currently,around50 drugs havebeenapprovedfor humanuseagainstvirusessuchasHSV,HIV-1,thecytomegalo virus,theinfluenzavirus,HBVandHCV.Advancementsinthisareahavebeenachievedthrough effortsandtechnicalbreakthroughsindifferentscientificfields.Theimprovementinthe treat-ment ofHCVinfectionisagoodexampleofwhatisneededforefficientantiviraltherapy.A thoroughdescriptionoftheeventsthatleadtothedevelopmentofspecificallytargeted antivi-raltherapyorHCV(STAT-C)couldbeusefultofurtherimproveresearchfortreatingmanyother viraldiseasesinthefuture.SimilartoHIV-1andHBVtreatment,combinationtherapyalongwith personalizedmedicineapproacheshavebeennecessarytosuccessfullytreatHCVpatients.This reviewisfocusedonwhathasbeendonetodevelopasuccessfulHCVtherapyandthedrawbacks alongtheway.

©2014UniversidadAutónomadeNuevoLeón.PublishedbyMassonDoymaMéxicoS.A.Thisis anopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Abbreviations: TFT,triflouro-thymidine;HCV,HepatitisCvirus;IFN,interferon;SVR,sustainedvirologicresponse;STAT-C,specifically

targetedantiviraltherapyforHepatitisC;DAAs,direct-actingantiviralagents.

∗Correspondingauthorat:DepartamentodeBioquímicayMedicinaMoleculardelaFacultaddeMedicinayHospitalUniversitario‘‘Dr. JoséEleuterioGonzález’’delaUniversidadAutónomadeNuevoLeón,Av.FranciscoI.MaderoyEduardoAguirrePeque˜nos/nCol.Mitras Centro,CP64460Monterrey,N.L.,Mexico.Tel.:+528183294174;fax:+528183337747.

E-mailaddress:amrivas1@yahoo.ca(A.M.Rivas-Estilla).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmu.2015.05.003

Introduction

From1972 to date, more than 50 newviruses have been identifiedasetiologicagentsofhumandisease.1Thesenew

viraldiseaseshaverequiredmoresophisticatedtherapeutic agents,butthedevelopmentprocessofthesestrategiesto thispointhasbeenslowandfullofhurdles.

Antiviralchemotherapyhasadvancedatsnail-likepace, unlikeantibiotics,whichin30yearsachievedanadvanced therapeuticstage.34yearselapsedfromthedescriptionof theantibacterialmoleculesalvarsan, ‘‘themagic bullet’’, byEhlrichin1910,2tothediscoveryofpenicillinbyFleming

in1929,3toDomagk’sdescriptionofprontosil,theprecursor

ofsulfonamidesin19354andtheisolationofstreptomycin,

chloramphenicol,erythromycin and tetracycline by Waks-manin1944.5However,ittookalmost60yearsforantiviral

developmentto reachits current status of effectiveness. The evolution of the treatment for Hepatitis C is a good exampleofhowcomplexantiviraldevelopmentcanbeand howacombinedandspecifictargetedantiviraltherapyhas provedtobethebestapproachtofollowfor viraldisease treatment.

TheHepatitisCvirus(HCV)affectsover170million indi-vidualsworldwide,80%ofwhicharechronicallyinfected.6

Thisisfourtimes thenumberofpeopleinfectedwithHIV and about half the number of persons infected with the HepatitisBvirus(HBV).7HCViscaused byahepatotropic

virus,whichbelongstotheFlaviviridaefamily,genus Hep-acivirus.HCVwasdiscoveredin1989anditsviralgenomeisa 9.6kb-longpositivesingle-strandedRNA.Itencodesasingle polyproteinprecursorof3010aminoacidsandhasan inter-nalribosomeentrysiteatthe5′ untranslatedregion.This

polyproteinprecursorisco-translationallyprocessedby cel-lularandviralproteasesintothreestructuralproteins(core, E1andE2)andsevennon-structuralproteins(p7,NS2,NS3, NS4A,NS4B,NS5AandNS5B).8Thestructuralproteins

asso-ciatewiththegenomicRNAandaviralparticleisassembled insidealipidicenvelope.

Treatment for HCV infection has come a long way. Between2001and2011,astandardofcare(SOC)forchronic HCV infection was established worldwide. It consisted of acombinationof pegylatedinterferon (PEG-IFN)and riba-virin(RBV). Nowadays, newspecific antiviral agents have beenapproved.InMay2011,boceprevirandtelaprevir,two first-generation NS3/4A protease inhibitors, were autho-rized for their use in combination withPEG-IFN and RBV for a24-to-48-week course oftreatment in HCV-genotype 1 infections. Two years later (December 2013), Simepre-vir (a second-generation NS3/4A protease inhibitor) was approved for use with PEG-IFN and RBV for a 12-week course of treatment in HCV-genotype 1, while sofosbu-vir(aNS5Bnucleotidepolymeraseinhibitor)wasapproved forusewithPEG-IFNand/or RBVfor a12/24-weekcourse of treatment in HCV-genotypes 1 to4. IFN-free regimens have been shown to give better results, because sofos-buvir, combined with simeprevir or an NS5A replication complexinhibitor (ledipasvirordaclatasvir),withor with-outRBV for a 12-week treatment in genotype 1, resulted inasustainedvirologicalresponse(SVR)>90%.Inaddition, ABT-450/r (ritonavir-boosted NS3/4A protease inhibitor)-based regimens, in combination with other direct-acting antiviral agent(s) with or without RBV for 12 weeks in

genotype 1, have demonstrated similar results regarding SVR.9

Roadblocks

for

antiviral

drug

development

As we see in the text above, therapy for HCV infection remainedalmostthesamefrom2001to2011.Afteradecade ofpoorlyeffectiveHCVtherapy,thedevelopmentofspecific compoundsagainstthisvirusrampedupHCVtreatmenton apacethatnearlymatched antiretroviraltherapyforHIV. ‘‘Whydidittakesuchalongtime?’’isanimportantquestion whose answer couldhelpontheapproaches towardsdrug developmentagainstuntreateddiseases.Thefirst complica-tionwhenstudyingavirusisthelimitationsregardinginvitro

systemsandanimalmodelsforexperimentation;second,is thelowrateofdiscoveryforefficientcandidatemolecules, and third,the delicatebalance betweenefficacy, toxicity and resistance towards the selected antiviral drug. Addi-tionaleconomicalaspectsmustalsobeconsidered.Herewe haveanalysedeachoftheseaspectsunderthelightofthe promises and pitfalls related toHepatitis C research and treatment.

HCV

study

tools

Virusesareintracellularorganismswhichdependoncellular machineryforreplication.Therefore,ahugebreakthrough in this field was achieved by Enders, Robbins and Weller in 1951, when they developed an in vitro virus propaga-tionsystemincellculture.10Sincethen,manyinvitroand

in vivo systems have been implemented for the study of severalviruses, suchaspolioandHIV. Cell assayssystems were recently developed for HCV infection and propaga-tion.IntheearlybeginningsofHCVstudies,nosmallanimal model existed tostudy HCVinfections, andChimpanzees, theonlyanimalscapableofbeinginfectedwithHCV,were precluded by both ethicaland functional difficulties.The

in vitro development for HCV research began with the sub-genomic replicon cell culture system that replicates autonomouslyinthehumanhepatomacelllineHuh-7 gener-atedbyBartenschlageretal.,in2001.11,12Thissub-genomic

repliconmodel wasfurtherimproved bytheidentification and introduction of adaptive mutations, which enhanced virusreplicationcapacityandleadtotheestablishmentof thefull-lengthrepliconsystem usingthehighlypermissive cell line Huh-7.5.1 in 2003, by Blight and Bartenschlager et al., separately.13---15 These developments allowed the

studyofHCVinfectionmechanisms,suchaspackaging, bud-ding andamoreaccurateevaluationof potentialantiviral molecules.Ontheotherhand,thedevelopmentofasmall animal model that can be infected with HCV became a reality with the T- and B-cell deficient mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), grafted with human hepatocytes. The firstHCVinfectionstudies inthis model were performed byMercer etal. in2001. Inrecent years thedevelopmentoftransgenicmicewithachimeric mouse-humanliverrevolutionizedHCVinfectionresearch,allowing theassessment ofpathologicaland immunologicalprofiles ofthedisease.16Today,scientistsrelyonacombination of

profilingin animalsas proxy indicators of antiviral drugs’ efficacy,beforeattemptingclinicaltrials.17

Screening

process

for

antiviral

drug

discovery

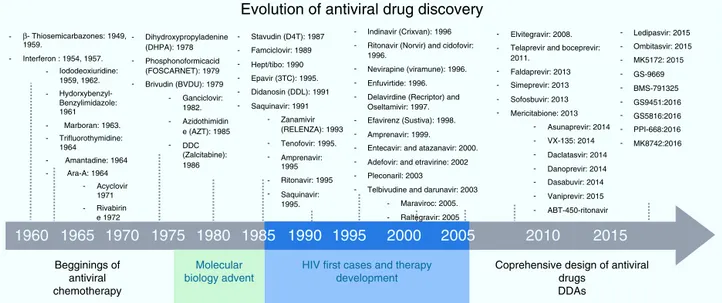

Anotheraspect that madeantiviral drugdiscovery a diffi-cultendeavorwasthelack ofastructuredandsystematic methodforantiviraldrugdevelopment.Threedecadesago most of the first discoveries of antiviral compounds were fortuitous, since molecules originally developed for other purposes were selected as antiviral candidates, based on their success in other medical disciplines. These meth-ods for antiviral discovery were empirical, and most of the time, the biological mechanism behind the observed antiviraleffectremainedunclear.Forinstance,theuseof thio-semicarbazonesagainstthevacciniavirus,describedin 1950byHamreetal.,andusedlaterasanantibacterialdrug against tuberculosis.18 In 1959, the 5-iodo-2-deoxyuridine

(IDU),whichwasoriginallydesignedforcancertreatment, provedtoexhibitantiviralactivityagainsttheHerpesVirus, butduetoitshighcytotoxicity,itsusewaslimitedtotopical application. IDUboostedantiviral development,and from its discovery many antiviral molecules were proposed for thetreatment ofvariousviraldiseases.19 InFig.1,atime

lineofthemilestonesinthedevelopmentofantiviralagents showstheearlyyearsofthisdisciplineandhowitevolvedto becomeastructuredandmethodicscience.20Atthetimeof

IDUdiscovery,onlyahandfulofviruseswereknowntocause diseasesinhumans.The firstantiviraldrugsweredirected totreatherpes,polio,smallpoxandinfluenza,astheywere themostrelevantviraldiseasesofthattime.Someofthem

thatwecanmentionarethefollowing:triflouro-thymidine (TFT), a nucleoside analogue used to treat herpes; ade-ninearabinoside(Ara-A)anucleosideanalogueagainstthe herpessimplexvirus21;2-(␣-hydroxybenzyl)benzimidazole

forthetreatmentofpoliomyelitis;Marboranforthe treat-mentofsmallpoxandamantadineandrimantadinetotreat influenza, which were identified by traditional biological screening assays in the early 1960s and was shown to be inhibitory for influenza A viruses in cell culture and animal models.In thelast twodecades,medicinal chem-istry hasdeveloped intoa recognizeddiscipline, in which a lead compound was usually identified by screening a large collectionof molecules. This method was improved withtheintroductionofcombinatorialchemistryand high-throughputscreening.22 Today,more structuredrationales

areimplementedwhenlookingfornewantiviraldrugs; sim-plescreening, blind screening and programmed screening have become more sophisticated, as the tools to ana-lyzestructure,proteininteractionandviralbehaviorhave evolved.ForHCVtherapydevelopment,manyattempts to treat the infection were implemented, with rather poor results.23 Duetothelack ofaserologicaltest, systematic

treatmentprotocolscouldnotbeperformed,andsoseveral ‘‘informal’’studieswerereported,evaluatingmanykindsof molecules.Butitwasnotuntil1986thatHoofnaglereported thebeneficialeffectofInterferonAlphainapilotstudyto treatNon-A/Non-Bhepatitis.24Thisreportprimedaboomin

HCVtherapeuticsandmanyrandomizedcontrolledclinical trialswereperformed toimproveHCVtreatment. In1990 RibavirinwasfirstproposedtotreatHCVinfectionandthe firstclinical trial for the assessment of itsefficacy began in 1991.25,26 After the efficacy of the combined antiviral

Receptor

Co-receptor Attachment

Virus

Replication

+ RNA Fusion

NS5A

Endoplasmic reticulus

Nucleus

Protease

Budding Maturation

Assembly

Protein maturation

RNA

dependent-RNA polymerase DNA

Uncoating

Ires directed translation

Poly-protein

Golgi membranes

None

None None

None

None

None

Boceprevir, telaprevir, sineprevir, faldaprevir, vaniprevir, MK5-172, GS-9451, danoprevir, asunaprevir.

Sofosbuvir, Meriditabine, VX-135, Dasabuvir, BMS-791325, GS-9669

Daclatasvir, ledipasvir, GS-5816, PPI-668, Ombitasvir, MK-8742

progenie Viral

Evolution of antiviral drug discovery

Dihydroxypropyladenine Stavudin (D4T): 1987 Indinavir (Crixvan): 1996 Elvitegravir: 2008. Ledipasvir: 2015 Ombitasvir: 2015 MK5172: 2015 GS-9669 GS9451:2016 GS5816:2016 PPI-668:2016 MK8742:2016 BMS-791325 2011. Faldaprevir: 2013 Simeprevir: 2013 Sofosbuvir: 2013 Mericitabione: 2013 Asunaprevir: 2014 VX-135: 2014 Daclatasvir: 2014 Danoprevir: 2014 Dasabuvir: 2014 Vaniprevir: 2015 ABT-450-ritonavir Telaprevir and boceprevir: Ritonavir (Norvir) and cidofovir:

1996.

Nevirapine (viramune): 1996.

Enfuvirtide: 1996.

Delavirdine (Recriptor) and Oseltamivir: 1997.

Efavirenz (Sustiva): 1998.

Amprenavir: 1999.

Entecavir: and atazanavir: 2000.

Pleconaril: 2003 Adefovir: and etravirine: 2002

Telbivudine and darunavir: 2003

Maraviroc: 2005. Famciclovir: 1989

Hept/tibo: 1990

Epavir (3TC): 1995.

Didanosin (DDL): 1991

Saquinavir: 1991 Zanamivir (RELENZA): 1993 Tenofovir: 1995. Amprenavir: 1995 1995. Ritonavir: 1995 Saquinavir: (DHPA): 1978 Phosphonoformicacid (FOSCARNET): 1979

Brivudin (BVDU): 1979

Ganciclovir: 1982.

Azidothimidin e (AZT): 1985

DDC (Zalcitabine): 1986 1959.

Interferon : 1954, 1957. Iododeoxiuridine: 1959, 1962. 1961 1964 Ara-A: 1964 Acyclovir

1960

Begginings of antiviral chemotherapy Molecular biology adventHIV first cases and therapy development

Coprehensive design of antiviral drugs

DDAs

1965

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

2015

1971 Rivabirin e 1972 Amantadine: 1964 Marboran: 1963. Trifluorothymidine: Hydorxybenzyl-Benzylimidazole:

-β Thiosemicarbazones: 1949,

-- -Raltegravir: 2005

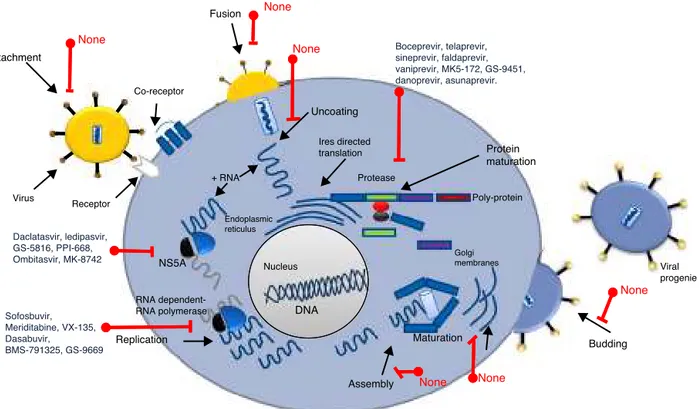

Figure2 HCVPotentialtargetsforantiviralchemotherapy.ManytargetsforantiviralactioncanbefoundalongHCV’slifecycle.

therapyofPegylatedInterferon-␣(PEG-IFN-␣)andribavirin againstHCVinfectionwasproven,itbecamethestandardof care(SOC)forthisdisease,anddespiteitsshortcomings(50% responserateand50%relapserateonpatientsinfectedwith genotype 1b, andunwanted side effects), it remained as suchformorethan15years.27,28Duringthistime,usingblind

screeningapproaches,somemoleculeswerefoundtoreduce HCV-RNAlevelsinvitro,butnoneofthemweresignificant enoughtobeimplementedclinically.ItwasnotuntilMay, 2011thattheimprovedunderstandingoftheHCVlifecycle ledtothediscovery,assessmentandFDAapprovaloftheHCV protease inhibitors Telaprevir and Boceprevir, that effec-tivelyreduceviral loadonchronicHCVinfected patients, in treatment of naïve patients and in prior relapsersand non-responders.29,30Telaprevirandboceprevirwerethefirst

direct-actingantiviralagents(DAAs)thatselectivelytarget HCV.However,newDDAshavebeenrecentlyaddedtothis list:simeprevir(proteaseinhibitor),sofosbuvir(NS5b poly-meraseinhibitor),daclatasvir(NS5Aproteininhibitor),and faldaprevir(second-waveNS3/4Aproteaseinhibitor),allof themshowing very promisingresults and some have even been proposedasthe treatment backbone for Interferon-freeHCVtherapies.31,32 WiththeseselectiveHCVprotease

inhibitors, the establishment of STAT-C therapy became a reality. Today, several DAAs (including HCV protease inhibitors,polymeraseinhibitors,andNS5Ainhibitors)arein variousstagesofclinicaldevelopment.Currentresearchis attemptingtoimprovethepharmacokineticsand tolerabil-ityoftheseagents,definethebestregimens,anddetermine treatmentstrategiesthatproducethebestoutcomes.Some of these DAAs will reach the market simultaneously, and resourceswillbeneededtoguidetheuseofthesedrugs.It isalsoworthmentioningthatdifferentlinesofresearchare currentlyevaluatingotherwaystoimproveHCV chemother-apy.Forexample,taribavirin,aprodrugforthelong-known nucleosideanalogue ribavirin, is at 3rdphase clinical tri-als and has shown promising results.33 This new antiviral

would further boost HCV therapy in the coming years.

Fig.2shows the majorHCVpotentialtargets for antiviral chemotherapy.

Efficacy

and

toxicity

on

the

development

of

an

efficient

antiviral

drug

SincethediscoveryofIDU50yearsago,onlyafewmolecules haveproventobeeffectiveandsafewhenusedfor selec-tive antiviral therapy. A huge breakthrough that came fromthebetterunderstandingofvirus-hostinteractionwas the inception of 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl) guanine (Acy-clovir).Itwasthefirsthighlyselectiveantiviraldrug,beinga substratefortheHerpesSimplexVirus-encoded thymidine-kinase.It displayedadirectinhibitory effectagainstviral replicationandpracticallynoadverseeffectsonthehost. TheachievementofselectiveviraltoxicitybyAcyclovirand other similar molecules werethought of asthe beginning of anewtherapeuticagefor awell-established,effective and safe antiviral therapy.Acyclovir is a pro-drug, which meansithastobefurthermetabolizedinvivobefore enter-ing the infected cell wherein further metabolism may or maynotberequired toyield theactiveinhibitor.The key to Acyclovir’s specificity is the selective phosphorylation of the acyclic guanosine nucleoside by the Herpes virus-encoded pyrimidinedeoxynucleoside kinase, whichmeans it would only be active on Herpes-infected cells.34 After

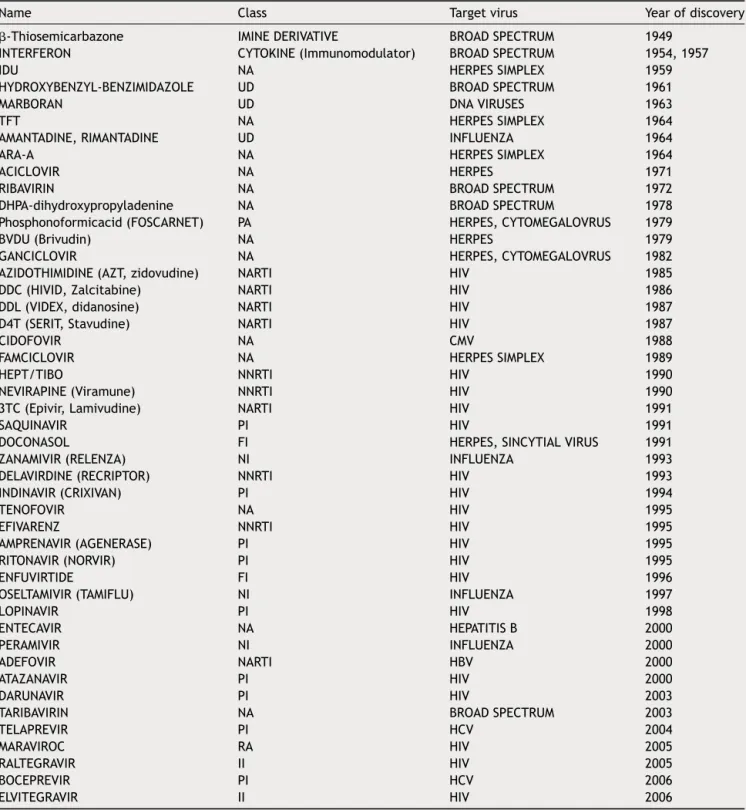

Table1 Majorantiviralcompoundsdevelopedandapprovedforuseinhumans.

Name Class Targetvirus Yearofdiscovery

-Thiosemicarbazone IMINEDERIVATIVE BROADSPECTRUM 1949

INTERFERON CYTOKINE(Immunomodulator) BROADSPECTRUM 1954,1957

IDU NA HERPESSIMPLEX 1959

HYDROXYBENZYL-BENZIMIDAZOLE UD BROADSPECTRUM 1961

MARBORAN UD DNAVIRUSES 1963

TFT NA HERPESSIMPLEX 1964

AMANTADINE,RIMANTADINE UD INFLUENZA 1964

ARA-A NA HERPESSIMPLEX 1964

ACICLOVIR NA HERPES 1971

RIBAVIRIN NA BROADSPECTRUM 1972

DHPA-dihydroxypropyladenine NA BROADSPECTRUM 1978

Phosphonoformicacid(FOSCARNET) PA HERPES,CYTOMEGALOVRUS 1979

BVDU(Brivudin) NA HERPES 1979

GANCICLOVIR NA HERPES,CYTOMEGALOVRUS 1982

AZIDOTHIMIDINE(AZT,zidovudine) NARTI HIV 1985

DDC(HIVID,Zalcitabine) NARTI HIV 1986

DDL(VIDEX,didanosine) NARTI HIV 1987

D4T(SERIT,Stavudine) NARTI HIV 1987

CIDOFOVIR NA CMV 1988

FAMCICLOVIR NA HERPESSIMPLEX 1989

HEPT/TIBO NNRTI HIV 1990

NEVIRAPINE(Viramune) NNRTI HIV 1990

3TC(Epivir,Lamivudine) NARTI HIV 1991

SAQUINAVIR PI HIV 1991

DOCONASOL FI HERPES,SINCYTIALVIRUS 1991

ZANAMIVIR(RELENZA) NI INFLUENZA 1993

DELAVIRDINE(RECRIPTOR) NNRTI HIV 1993

INDINAVIR(CRIXIVAN) PI HIV 1994

TENOFOVIR NA HIV 1995

EFIVARENZ NNRTI HIV 1995

AMPRENAVIR(AGENERASE) PI HIV 1995

RITONAVIR(NORVIR) PI HIV 1995

ENFUVIRTIDE FI HIV 1996

OSELTAMIVIR(TAMIFLU) NI INFLUENZA 1997

LOPINAVIR PI HIV 1998

ENTECAVIR NA HEPATITISB 2000

PERAMIVIR NI INFLUENZA 2000

ADEFOVIR NARTI HBV 2000

ATAZANAVIR PI HIV 2000

DARUNAVIR PI HIV 2003

TARIBAVIRIN NA BROADSPECTRUM 2003

TELAPREVIR PI HCV 2004

MARAVIROC RA HIV 2005

RALTEGRAVIR II HIV 2005

BOCEPREVIR PI HCV 2006

ELVITEGRAVIR II HIV 2006

NA:nucleosideanalogue;NARTI:nucleosideanalogue-reversetrancriptaseinhibitor;UD:undetermined;PA:pyrophosphateanalogue; NNRTI:non-nucleosideanalogue-reversetrancriptaseinhibitor;NARTI:nucleosideanalogue-reversetrancriptaseinhibitor;PI:protease inhibitor;FI:fusioninhibitor;NI:neuraminidaseinhibitor;RA:receptorantagonist;II:integraseinhibitor.

HIV.Thescienceofantiviralresearchwaswell established whenHIV/AIDS appeared asamajorviraldisease inearly 1980s.Anincreaseofantiviraltherapystudieswithnoequal tookplacewhenthefirstcasesofHIVwerereported. Azi-dothymidine(AZT),amongotherantiviralmoleculesalready inexistence,provedtohaveselectivetoxicityagainstHIV.

170

O.L.

Bryan-Marrugo

et

al.

Table2 SummaryoftherecenttreatmentguidelinesforHCVinfectiontherapy[describedbytheAmericanAssociationfortheStudyofLiverDiseases(AASLD),Infectious DiseaseSocietyofAmerica(IDSA)andtheInternationalAntiviralSociety(IASUSA)].

HCVgenotype Naïvepatientsb Non-responderstotraditionalIFN-RBV

therapy

Resistantto Sofosbuvir

Resistantto traditional therapyand1st generation protease inhibitors

Patientswith Cirrhosisb

1a CombinationofLedispavir90mg/sofosbuvir

400mgfor12wks

CombinationofLedispavir90mg/sofosbuvir 400mgfor12wks

Combinationof Ledispavir 90mg/sofosbuvir 400mgfor12 wks

Extend treatmentfor 24wks

Paritaprevir150mg/ritonavir

100mg/ombitasvir25mg/twicedailydose ofdasabuvir250mgandRBVafor12wks

Paritaprevir150mg/ritonavir

100mg/ombitasvir25mg/twicedailydose ofdasabuvir250mgandRBVafor12wks

CombinationOf Ledispavir 90mg/sofosbuvir 400mgplus RBVafor12

wks.

Extend treatmentfor 24wks

Sofosbuvir400mg/Simeprevir150mg/RBVa

for12wks

Sofosbuvir400mg/Simeprevir150mg/RBVa

for12wks

Extend treatmentfor 24wks

1b Ledipasvir90mg/sofosbuvir400mgfor12

wks

Ledipasvir90mg/sofosbuvir400mgfor12 wks

Ledispavir 90mg/sofosbuvir 400mgplus RBVa

CombinationOf Ledispavir 90mg/sofosbuvir 400mgfor12 wks

Extend treatmentto 24wks

Paritaprevir150mg/ritonavir

100mg/ombitasvir25mg/twicedailydose ofdasabuvir250mgfor12wks

Paritaprevir150mg/ritonavir

100mg/ombitasvir25mg/twicedailydose ofdasabuvir250mgfor12wks

CombinationOf Ledispavir 90mg/sofosbuvir 400mgplus RBVafor12

wks.

PlusRBV

Sofosbuvir400mg/Simeprevir150mgfor12 wks

Sofosbuvir400mg/Simeprevir150mgplus RBVafor12wks

Extend treatmentfor 24wks

2 Sofosbuvir400mgandRBVafor12wks Sofosbuvir400mgandRBVafor12wks Extend

treatmentfor 16wks Sofosbuvir400mgandRBVaplusweekly

PEG-IFNfor12wks

History

and

progress

of

antiviral

drugs

171

Table2 (Continued)

HCVgenotype Naïvepatientsb Non-responderstotraditionalIFN-RBV

therapy

Resistantto Sofosbuvir

Resistantto traditional therapyand1st generation protease inhibitors

Patientswith Cirrhosisb

Sofosbuvir400mg/RBVaplusWeekly

PEG-IFNfor12wks

Sofosbuvir400mgandRBVaplusweekly

PEG-IFNfor12wks

4 Ledipasvir90mg/Sofosbuvir400mgfor12

wks

Ledipasvir90mg/Sofosbuvir400mgfor12 wks

Paritaprevir150mg/ritonavir

100mg/ombitasvir25mg/andRBVafor12

wks

Paritaprevir150mg/ritonavir

100mg/ombitasvir25mg/andRBVafor12

wks

Sofosbuvir400mg/RBVafor24wks Sofosbuvir400mgplusRBVaplusWeekly

PEG-IFNfor12wks Sofosbuvir400mgplusRBVaplusWeekly

PEG-IFNfor12wks

Sofosbuvir400mgplusRBVafor24wks

5 Sofosbuvir400mgplusRBVaplusWeekly

PEG-IFNfor12wks

Sofosbuvir400mgplusRBVaplusWeekly

PEG-IFNfor12wks

WeeklyPEG-IFNplusRBVafor48wks WeeklyPEG-IFNplusRBVafor48wks

6 Ledispavir90mg/Sofosbuvir400mgfor12

wks

Ledispavir90mg/Sofosbuvir400mgfor12 wks

Sofosbuvir400mgplusRBVaplusweekly

PEG-IFNfor12wks

Sofosbuvir400mgplusRBVaplusweekly

PEG-IFNfor12wks

a RBV(Ribavirin)dosageisweightbased(1000mg[<75kg]and1200mg[>75kg]).

Allindicationsrefertodailydosesunlessisotherwiseclarifiedinthetext. b Definitionsfortreatmentcriteria.42,43

(Treatment)Naïvepatient:ApersonwhohasneverundergoneanyHCVtherapy.

---RapidVirologicResponse(RVR):ItisdefinedasanundetectableHCVRNAatweek4oftreatment.

---SustainedVirologicalResponse(SVR):ItisdefinedasundetectableHCVRNA12weeks(SVR12)or24weeks(SVR24)aftertreatmentcompletion.

---Non-response:ReferstoapatientwhodonotachieveundetectableHCVRNAduringthefirst24weeksoftreatment.Therearetwoformsofnon-responders:Partialrespondersand nullresponders.

---Partialresponse:Itisasub-categoryofnon-responseanddescribesadecreaseinHCVRNAlevelsbyatleast2Log10atweek12oftreatmentbutdetectablelevelsatweek24. ---Nullresponse:Isasub-categoryofnon-responseandreferstothesituationwhenapatientdoesnotsuppresstheirHCVRNAlevelsbyatleast2Log10byweek12oftreatment. ---Drugresistant:ApatientwhoisPartialorNullrespondertoaspecifictreatmentforwhichaHCV‘‘resistant’’mutantremainsimmunemakingnecessarytochangethetherapeutical approach.

onpublichealth.Althoughantiviralresearchand develop-ment were ignited by the HIV threat, many HIV patients werenotresponsivetothetreatment.ThediscoveryofAZT wasfollowedbyseveralotherdideoxynucleoside(ddN) ana-logues (ddI, ddC, d4T, 3TC, ABC, FTC) (Fig.2). All these NRTIsact ina similarfashion; aftertheir phosphorylation to triphosphates, they interact as ‘chain terminators’ of theHIV-reversetranscriptase,thuspreventingtheformation ofthe proviralDNA. Even though theyhad greatsuccess, drugresistance forced HIV treatment to evolve.Today, it isknownthat twoinevitable andimportantconsequences of antiviral therapy have to be taken into account when planning a treatment strategy for viral chronic diseases. Thefirstisthat,givenitsnature,long-termantiviral ther-apyautomaticallyselectsresistantmutantsthatwillsurvive andbecomedominantstrains.Resistant mutantsareeven morefrequentinviralthaninbacterialinfection,andthis becomesmoreevidentwhentreatingchronicviralinfections suchasHIVandHCV.35---37 Forviralinfections,anyattempt

toattackthevirus’metabolismcouldhaveaneffectonhost cells. It is evident then, that modifications of these two aspectsof antiviral therapy,could improve the results of treatmentforchronicpatients.This barrierwasovercome inpart throughtheuseof combinatorial therapy.In addi-tiontothat,theconceptofabroadspectrumoratleasta ‘‘pangenotypic’’antiviralmoleculethatcouldbeeffective on a wide range of viral pathogens is paradoxically self-defeatingifwethinkthatspecificityisrequiredtoavoidcell toxicityandtheoppositeisneededtobroadenthespectrum ofagivenantiviral molecule.Withourcurrent knowledge onviralmetabolismandhost interaction,threeaspectsof viralinfectioncanbetargetedforantiviraltreatment: inhi-bitionofviralgenesandproteins,blockingofhostgenesand enzymesthatinteractwithviralcounterparts,and modula-tionof host metabolic pathways involved inthe virus life cycle.

The

challenges

of

fighting

Hepatitis

C

As we mentioned before, a new era of therapeutics is currently emerging for Hepatitis C treatment, since sev-eral other direct-acting HCV antiviral drugs are being developed (Protease inhibitors: faldaprevir, asunaprevir, danoprevir,vaniprevir,ABT-450-ritonavir,MK5172,GS-9451; NS5A inhibitors: ledipasvir, ombitasvir, GS-5816, PPI-668, MK-8742 and daclatasvir; NS5b inhibitors: mericitabine, VX-135,dasabuvir,BMS-791325,GS-9669),whichhavebeen shown to reduce viral RNA levels, reaching SVR in up to 95%ofthetreatedpatients.38,39However,thereareseveral

challengestobeaddressedtocombatHCVusingnewdrugs. DAA’sdirectly attack the Hepatitis C virus and,similar to someofthedrugs usedtotreat HIV,thesenewmolecules targettheenzymesneededforviralproteinprocessing;the virusshouldcounterpartthiseffect(Fig.2).Basedonthat, HCVgeneticvariabilityand drugresistancearethebigger obstaclesthat DAAs must overcome. HCVhas a high rate ofreplication,with1012 virionsproduceddaily, alongwith

anequallyhighmutationrate,meaningthat,foranygiven drug,there are already resistant mutants present onthe infectedsubjectthatwouldultimatelyrendersingledrugs useless.However,HepatitisCresistancemaybedelayedor

prevented byusing combinationsofpotent antiviral drugs without cross-resistance profiles and optimizing patient adherence to therapy.38 On the other hand, accessibility

tothe new andapproved HCVtherapies is a challenge in combating the Hepatitis C, mainly because of the high cost of the combined treatments (between 100,000 and 250,000USD).Availabilityandaccessibilityofnewprotease inhibitors (PI), telaprevir, boceprevir, simeprevir, and the recentlyapprovedRNApolymeraseinhibitor(RPI)sofosbuvir dependsontheregionwherepatientsarelocatedandtheir accesstogovernmentalhealthprograms.Inmostcountries, accessibilitytothesedrugsispossibleonlyforthosepatients whocanaffordtreatmentforthemselves,aspublichealth systemsdonotyethavepoliciesforapplicationofthenew HCV therapy to the generalpopulation throughinsurance systems.40 This will likely require concerted public and

political mobilizationto pressure originator companiesto reduce prices andstimulategeneric competition.In addi-tion, lower prices could make widespread access to HCV treatmentpossibleinlowandmiddleincomecountries.

Where

we

stand

today

After almost 20 years since HCV’s discovery, today we account for a solid-yet-not-completely effective treat-ment landscapetofight hepatitisinfection. First,modern biomolecular diagnostictoolsareusedtodetermine geno-type and viral load as a base to design an accurate therapeutic regimen;second,viralloaddynamicsis moni-toredinordertodetermine drugresistance,andthirdthe liver’s state andthepresence ofinfectionareassessed in patients whohave completedthe therapy.In an effortto provideacondensedsetoftreatmentguidelines,the Amer-icanAssociationofLiverDisease(AASL),InfectiousDisease Society (IDSA)andthe InternationalAntiviralSociety (IAS-USA)generatedtheGuidelinesforHCVinfectiontreatment which are based on patient’s previous exposure to treat-ment,HCVgenotype,relapsingprofileandhepaticstatus.41

InTable2weshowacompendiumoftherecenttreatment guidelines for HCV infection therapy. It is important for physicianstoevaluatepatientclinicalhistory(naïveornot), HCVgenotype,treatmenteffectivenessandHIVco-infection inordertoavoidunwanteddruginteractions.

Conclusions

and

perspectives

virusfactorsarenottheonlypotentialtargetsforinhibition, buthosttargets areaswell,includingmicroRNAs,cellular receptors, adhesion molecules and cyclophilins. For the nearfuture,acombinationofhostandviralinhibitorswill provideavarietyofdrugregimesappropriatefordifferent patients that couldlead tointerferon-free therapies that canconsistentlycleartheinfection.

Aneweraof HCVtreatment andtheincreasing knowl-edge about viruses and their mechanisms of infection, combinedwiththerapiddiscoveryofnovelantiviral strate-giesandtechniques,willspeedupthedevelopmentofnovel antiviraldrugs.

Funding

FinancialsupportwasprovidedbytheCONACYT,grant num-berCB-2011-1-58781toA.M.R.E.

Conflict

of

interest

Theauthorshavenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

WethankSergioLozano-Rodriguez,M.D.for hisassistance inreviewingthemanuscript.

References

1.DesselbergU.Emergingandre-emerginginfectiousdiseases.J Infectol.2000;40:3---15.

2.FitzgeraldJG.Ehrlich-HataremedyforSyphilis.CanMedAssoc J.1911;1:38---46.

3.PorritAE.Thediscoverydevelopmentofpenicillin.MedPress. 1951;19:460---2.

4.DomagkG.Sulfonamidesinthepastpresentandfuture.Minerva Med.1950;35:41---7.

5.NeuHC,GootzTD.Antimicrobialchemotherapy.Medical micro-biology. 4th ed. Galveston, TX: University of Texas Medical Branch;1996[Chapter11].

6.JangJY, ChungRT. New treatments for chronic hepatitis C. KoreanJHepatol.2010;16:263---77.

7.MoradpourD,PeninF,RiceCM.ReplicationofhepatitisCvirus. NatReviMicrobiol.2007;5:453---63.

8.BartenschlagerR,Ahlborn-Laake L, MousJ, et al.,Jacobsen H.Nonstructuralprotein3ofthehepatitisCvirusencodesa serine-typeproteaserequiredfor cleavageattheNS3/4and NS4/5junctions.JVirol.1993;7:3835---44.

9.FeeneyER,ChungRT.AntiviraltreatmentofhepatitisC.BrMed J.2014;349:3308.

10.RobbinsFC,EndersJF,WellerTH.Studiesonthecultivationof poliomyelitisvirusesintissueculture.V.Thedirectisolationand serologicidentification ofvirus strainsintissue culturefrom patientswithnon-paralyticand paralytic poliomyelitis.AmJ Hygene.1951;2:286---93.

11.BartenschlagerR,LohmannV.Novelcellculturesystemsforthe hepatitisCvirus.AntiviralRes.2001;1:1---17.

12.Lohmann V, Korner F, Kosch J, et al. Replication of subge-nomichepatitisCvirusRNAinahepatomacellline.Science. 1999;5424:110---3.

13.BlightKJ,McKeatingJA,MarcotrigianoJ,etal.Efficient repli-cationofhepatitisCvirusgenotype1aRNAsincellculture.J Virol.2003;5:3181---90.

14.WakitaT,PietschmannT,KatoT,etal.Productionofinfectious hepatitisCvirusintissueculturefrom acloneviralgenome. NatMed.2005;7:791---6.

15.BartenschlagerR,KaulA,SparacioS.Replicationofthe hepati-tisCvirusincellculture.AntivirRes.2003;2:91---102.

16.Ernst E, SchönigK, Bugert JJ. Generationof inducible hep-atitis C virus transgenic mouse lines. J Med Virol. 2007;8: 1103---12.

17.LinC.HCVNS3-4Aserineprotease.HepatitCVirusesGenomes MolBiol.2006;1:163---206.

18.Bauer D. Clinical experience with the antiviraldrug Marbo-ran(1-methyl.isatin3-thiosemicarbazone).AnnNYAcadSci. 1965;130:110---7.

19. Field HJ, De Clerk E. Antiviral drugs --- a short history of their discovery and development. Microbiol Today. 2004;31: 60---2.

20.Pierrel J.AnRNAphagelab:MS2 inWalterFiers’ laboratory ofmolecularbiologyinGhentfromgeneticcodetogeneand genome1963---1976.JHistBiol.2012;1:109---38.

21.Nesburn AB, Robinson C, Dickmson R. Adenine arabinoside effecton experimental idoxiuridine-resistant herpessimplex infection.InvestOphthalmolVisSci.1974;4:302---4.

22.XuH,AgrafiotisDK.Retrospectandprospectofvirtualscreening indrugdiscovery.CurrTopMedChem.2002;12:1305---20.

23.ChooQL,KuoG,WeinerA.AcDNAclonederivedfroma blood-bornenon-A,non-Bviral.Science.1989;4902:359---62.

24.HoofnagleJH,MullenKD,JonesB,etal.Treatmentofchronic non-A,non-BHepatitiswithrecombinanthumanalfainterferon. Apreliminaryreport.NEnglJMed.1986;25:1575---8.

25.ReichardO, AnderssonJ.Ribavirin:apossiblealternativefor thetreatmentofchronicnon-A,non-Bhepatitis.ScandJInfect Dis.1990;4:509.

26.ReichardO,AnderssonJ,SchvarczR,etal.Ribavirintreatment forchronichepatitisC.Lancet.1991;337:1058---61.

27.SherlockS.Antiviraltherapyforchronichepatitisinfection.J Hepatol.1995;23:3---7.

28.Reichard O, Schuarcz R, Weiland O. Therapy of hepatitis C:alpha interferon and ribavirin. Hepatology. 1997;3 Suppl. 1:108s---11s.

29.TraynorK.Twodrugsapprovedforchronichepatitisinfection. AmJHealthSystPharm.2011;13(1176):2011.

30.JesudianAB,Gambarin-GelwanM,JacobsonIM.Advancesinthe treatmentofhepatitisCvirusinfection.GatroenterolHepatol. 2012;8:91---101.

31.YauAH,YoshidaEM.HepatitisCdrugs:theendofthepegylated interferon era and theemergence ofall-oralinterferon-free antiviralregimens.Aconcisereview.CanJGastroenterol Hep-atol.2014;28:445---51.

32.KimDY,AhnSH,HanKH.EmergingtherapiesforhepatitisC.Gut Liver.2014;8:471---9.

33.Palmer M, RubinR, Rustgi V. Randomised clinicaltrial: pre-dosing with taribavirin before starting pegylated interferon vsstandardcombinationregimenintreatmentnaïvepatients withchronichepatitisCgenotype1.AlimentPharmacolTher. 2012;36:370---8.

34.DeClercqE,FieldHJ.Antiviralprodrugs-thedevelopmentof successfulprodrugstrategiesforantiviralchemotherapy.BrJ Pharmacol.2006;1:1---11.

35.HeimMH.Interferons andhepatitis Cvirus.Swiss MedWkly. 2012;142:1---13.

36.Pfeiffer JK, Kirkegaard K. Bottleneck-mediated quasispecies restrictionduringspreadofanRNAvirusfrominoculationsite tobrain.ProcNatlAcadSci.2007;14:5520---5.

37.RomanoKP,AliA,AydinC,etal.Themolecularbasisofdrug resistanceagainsthepatitisCVirusNS3/4Aproteaseinhibitors. PLoSPathol.2012;7:1---15.

39.MalcomB,LiuR, LahserF,etal. SCH503034,a mechanism-based inhibitor ofhepatitis C virus NS3 proteasesuppresses polyprotein maturation and enhances the antiviral activity of alpha interferon in replicon cells. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother.2006;3:1013---20.

40.RehmanS,AshfaqUA,JavedT.Antiviraldrugsagainsthepatitis Cvirus.GenetVaccinesTherapy.2011;11:1---10.

41.Recommendationsfortesting,managing,andtreatinghepatitis C;2014,December.http://www.hcvguidelines.org

42.EuropeanAssociationfortheStudyoftheLiver. Recommenda-tionsontreatmentofhepatitisC;2014.http://www.easl.eu/ newsroom/latest-news/easl-recommendations-on-treatment-of-hepatitis-c-2014

![Table 2 Summary of the recent treatment guidelines for HCV infection therapy [described by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and the International Antiviral Society (IASUSA)].](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_es/6159167.182110/6.1216.66.1159.119.842/treatment-guidelines-infection-american-association-infectious-international-antiviral.webp)